It’s early April, and Mary H.K. Choi is double masked inside a San Antonio H-E-B, stressing over which flowers to buy her mother. She’s been analyzing the floral department’s array of resplendent bouquets for ten minutes, but finds some flaw with each one. Many arrangements include carnations, which are a no-go; a bruised petal rules out another. Choi tells this story in a smooth, carefully controlled voice on her mental health–focused mini podcast, Hey, Cool Life!, saying, “I just watched myself be so convinced that there was a bouquet out there that was perfect—I just wasn’t seeing it.”

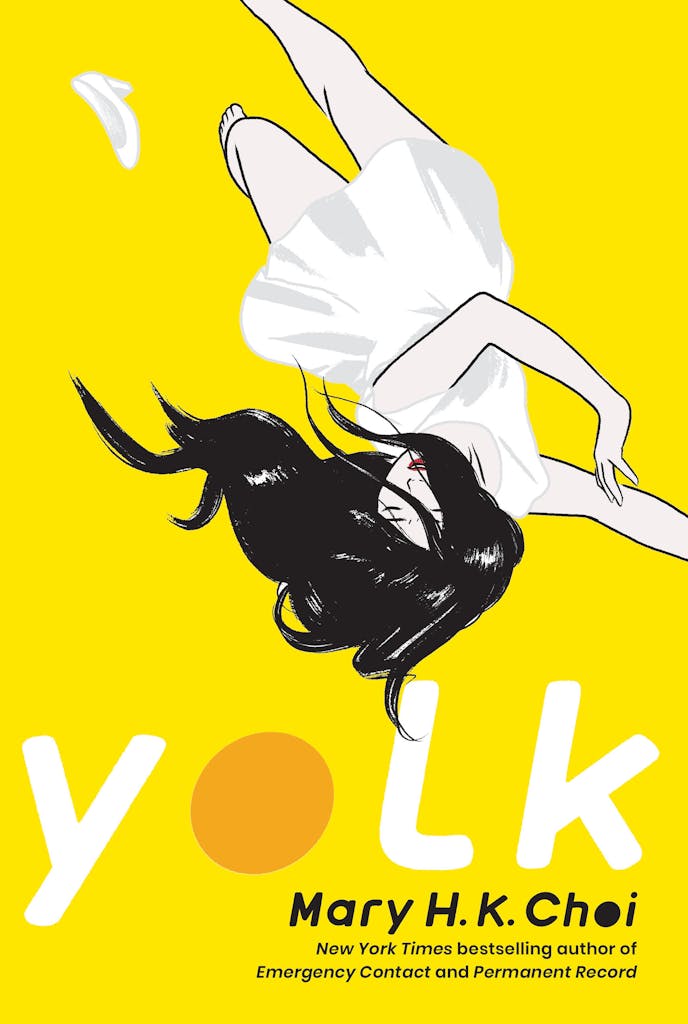

Choi says she knows the flowers are a proxy; life has been overwhelming lately, so she’s letting herself spin out about roses and ranunculuses. The New York Times–bestselling young adult just published her third novel, Yolk, last month, and then returned to Texas to look after her parents, with whom she has a complicated relationship. Last year, Choi’s mother was diagnosed with lung cancer (she is now cancer free); then came her father’s ALS diagnosis. The three-week visit was her longest trip home since she moved to New York City in 2002 at 22. Her mixed feelings these days—grief, compassion, resentment—are so overwhelming that she is allowing herself just the five to six minutes before falling asleep at night to cry and process, because the lights are out, and she won’t have the opportunity to obsess.

Choi spent most of the past two decades building an enviable career as a culture reporter. She’s interviewed stars like St. Vincent, Demi Lovato, and Geena Davis, and written cover stories for many of the glossy magazines you’d find on a newsstand—to say nothing of her years as the top editor at several publications. She’s even authored a few comic books. But all of this was adjacent to what she really wanted. Four years ago, she finally fulfilled her lifelong dream of becoming a novelist, with the publication of her first novel, Emergency Contact, in 2018. Her second, Permanent Record, followed in 2019. The latter is set to become a film, produced and possibly directed by Jon M. Chu (director of Crazy Rich Asians). Choi recently finished writing the script adaptation, and is an executive producer for the project.

Choi’s Texas homecoming is not unlike the one her characters in Yolk experience, when one of them is afflicted with cancer. It’s her most autobiographical book yet, though she’d already begun writing when she learned of her parents’ declining health—a distressing coincidence. The eating disorder central to the plot, the San Antonio and Korean roots, the illness, and the complicated family relationships are all particulars that Choi knows intimately.

Set between New York City and the San Antonio suburbs, Yolk follows two estranged sisters, June and Jayne, through the trials of the medical system and familial angst, expertly conveying the immigrant kid experience, fernweh (German for “farsickness,” a longing for unseen places) for oneself, and the self-imposed pressure to make it in New York. Like Choi, the protagonist is a child of workaholic restaurant-industry parents who speak limited English, and a cancer diagnosis stirs up compassion and resentment in equal measure. The tortuous emotions are plucked from Choi’s own life—in an essay titled “My mom: I love her and it’s a secret. I love her so much it kills me, and you bet I’d sooner die than tell her,” she writes about abstaining from birthday and holiday visits, and how on the rare occasions she does come home, she expresses affection in strange ways. “I wait for her to fall asleep and peer over her body and imagine what it’d be like if she died. I just stand there, hot silent tears coursing down my face.”

When Choi’s family moved from Hong Kong to suburban San Antonio, she was almost fourteen, and left behind not just a boyfriend, but the familiar neon glow of a cosmopolitan city where she felt safe and free to be herself. Gone was her independent, sophisticated lifestyle of taking cabs, riding the subway, and partying with friends. Hong Kong life had suited her.

“Texas gives great sky,” says a character in Yolk, “all oceanic and silencing.” And indeed, the wide, open landscape is what first gripped Choi. She’d never seen a shooting star until moving to Texas. “We didn’t have smartphones,” she tells me over Zoom, “so you would just sort of feel the weight of Texas because you weren’t so distracted. You’re just awash in horizon, and you’re like—this is so weird and slightly disembodying, but also really profound.”

Choi’s father moved the family to Universal City, a small San Antonio suburb outside of Randolph Air Force Base, where, at a high school of four thousand, aside from looking in the mirror, the only Asian faces Choi saw on campus were her brother’s and cousin’s. She remembers male classmates issuing racist snubs like “You’re really hot for an Asian,” and white girls touching her face, commenting on her “porcelain skin, just like a china doll.” At the time, these experiences felt more baffling than infuriating.

“I wasn’t angry, I was just so confused by what to feel,” she says, “because it was meant as a compliment, and it wasn’t hard for me to receive it in the way that it was expressed, but it was just so, like, three layers down to feel that discomfort.”

She blocked out the discomfort by reading voraciously, blazing through the school library and reading at least one title per day—books by Michael Crichton, Stephen King, John Grisham, whatever she could get her hands on. It was pure escapism and sanctuary; she developed an eating disorder that same year. Part of what makes the bingeing and purging scenes in Yolk so disquieting is the granular detail with which they’re written, recalling real-life methods Choi has referenced in interviews and essays about her struggle with bulimia, like avoiding the “telltale splash” of vomit hitting the toilet water by throwing up silently into your hand. It’s YA, but that doesn’t mean that Choi treats readers with kid gloves. Her writing is frank and clever, and the hard edges are chased with gentleness, evidenced in a note preceding page one, warning those struggling with body image and eating disorders that the story might be “emotionally expensive.”

As in her other novels, Choi imbues minimal scenes and details with meaning, so that readers’ emotions are stirred even as very little kinetic action is taking place on the page. One such example spans over ten pages of Jayne surveying her love interest’s “stylish in an aggressively retro way” apartment, taking in the enormous mustard leather sofa, clear plastic coffee table, and French-edition In the Mood for Love movie poster. She holds her breath, marveling at the La Croix, oat milk, and rotisserie chicken that share refrigerator space with kimchi, red pepper paste, and containers of prepared banchan. It’s just one long scene of comfortable, flirtatious banter, as Jayne breathlessly takes in these signifiers of the life she desperately wants. It’s less about the things themselves, and more about what they imply: a life that fits all the fragmented versions of herself.

With her coping mechanisms in place, Choi put her head down and persevered until she could escape, making a pit stop at the University of Texas to appease her parents; she’d never harbored college ambitions, and viewed the Forty Acres as just another gauntlet to run. After graduating with a degree in textiles and apparel, she beelined to New York City, bringing only a duffel bag and a suitcase. She told her parents nothing of the cross-country move until about two weeks into her new life; she’d already signed the lease on her Upper East Side apartment.

So finding herself back in San Antonio is bittersweet. Her virtual book tour segued into navigating the labyrinthian health care system, trying to find a licensed Korean medical interpreter for her father, who is losing control of his hands and the ability to lift his head. Despite it all, she’s choosing to enjoy things—Buc-ee’s, the brisket, fresh tortillas, iced tea, and wide streets. “Turns out I really like Texas,” she says.

The recent increase in violence against Asian Americans is yet another trauma she’s processing. Back in her Brooklyn neighborhood, Choi had scarcely left a four-block radius throughout the pandemic. There, she felt somewhat protected from the rampant hate crimes happening around the nation. After the Atlanta spa shootings that claimed the lives of six women of Asian descent, Choi recorded a podcast episode about feeling scared for her parents, but also angry at her inherited idea that if you are quiet, put your head down, and don’t make trouble, if you just work hard enough, “you will have progeny who will live these different lives.” Her parents believe this. But, she says, “They’re still gonna kill you . . . I really just wanted to protect them and also just tell them, like—deal’s off! . . . It’s a ruse! It’s a trap!”

That day at H-E-B, she eventually just settled on some wildflowers, a bouquet that she liked, and it was fine. “That had to just be enough,” she tells me later. But leaving the store, she deflated: “I also felt like I had already failed, and like, the bouquet I had picked was a capitulation.” She’s still struggling with perfectionism and self-criticism—challenges many readers can relate to. Choi often ends her podcast episodes cooing words of encouragement: “Be gentle with yourself.” It’s especially hard advice for Choi to take to heart, but she’s doing her best.

- More About:

- Books

- San Antonio