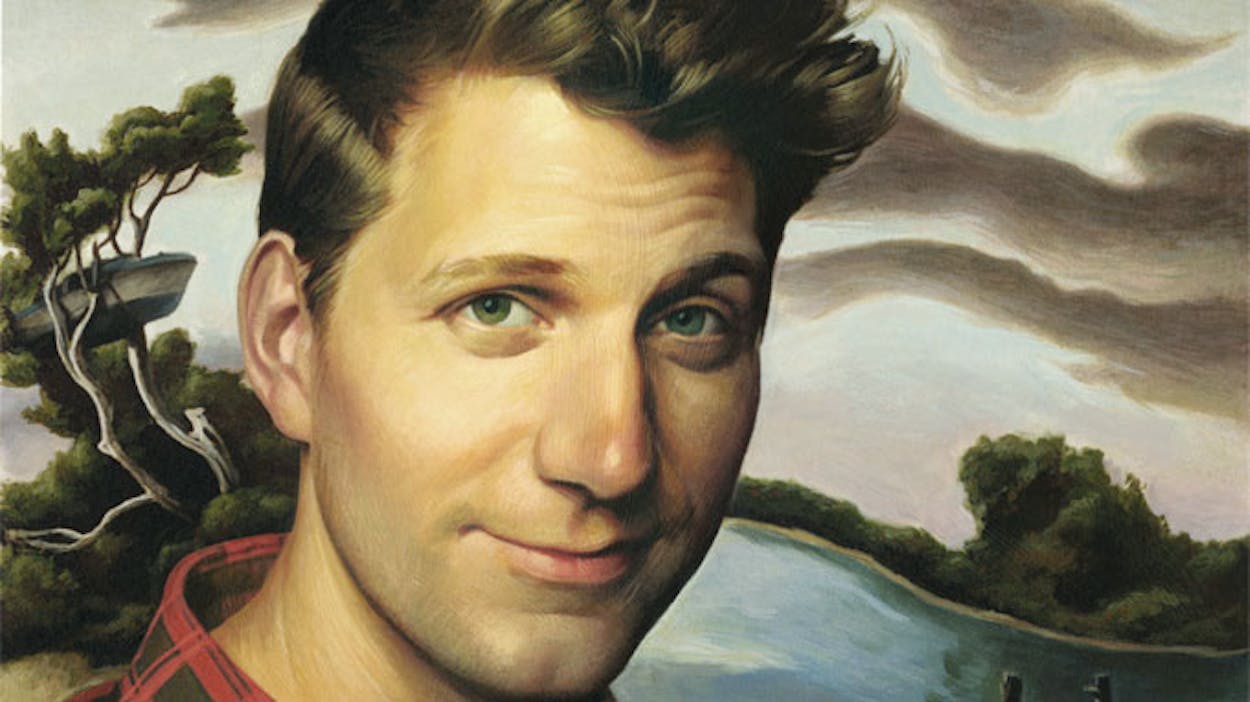

What does it mean, that oft-used term “all-American”? The Austin-based writer-director Jeff Nichols has flaxen brown hair, blue eyes, and an easy grin—if filmmaking hadn’t worked out, he could have made a go of modeling for J. Crew or Ralph Lauren. His biography has its share of red-blooded, meat-and-potatoes detail: the first movie he recalls his father taking him to see, when he was a second grader in Little Rock, was Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider.

Yet even as he draws on classic American legends for his screenplays and cites Mark Twain as a major influence, Nichols puts forth visions that are anything but conventional or white-bread. (Full disclosure: Nichols’s wife works for Texas Monthly’s custom publishing division.) His first feature, Shotgun Stories (2007), is a stark reimagining of the Hatfield and McCoy feud, about two sets of half-brothers who go to war after the funeral of their shared father. The follow-up, Take Shelter (2011), chronicles a possibly psychotic man haunted by hallucinations of a looming apocalypse. Set far from the usual indie hipster hot spots of Brooklyn and Los Angeles—Shotgun Stories takes place in rural Arkansas, Take Shelter somewhere in rural Ohio—these works suggest an America being crushed beneath the weight of worry. Characters brood about lousy wages, holding on to health insurance, and the challenge of putting food on the table. Without resorting to easy melodrama or noisy soap opera, Nichols conveys a sense of anxiety multiplying and spreading out in every direction.

The winning streak continues: late last month, Nichols’s third feature, Mud, opened in limited release nationwide. A twenty-first-century riff on Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the film follows two Arkansas boys who stumble across a murderer hiding out on a Mississippi River island. In some respects, it’s Nichols’s most conventional work to date, a straight-ahead, even sentimental tale of good versus evil that stars a pair of Hollywood A-listers, Matthew McConaughey and Reese Witherspoon. But the director doesn’t compromise his troubling portrait of modern life, and the movie’s combination of light and dark—at various points Mud evokes the adolescent goofiness of eighties comic adventures like The Goonies, the rough-and-tumble romanticism of mid-century film noirs like Gun Crazy, and the photographer Bill Owens’s elegiac, seventies-era portraits of middle- and working-class Americans—proves unusually provocative. Many of our most celebrated young directors love to cite the maverick Hollywood filmmakers of the seventies as their inspirations when they’re merely serving up elaborate exercises in style and pastiche. Nichols, though, seems determined to pick up the gauntlet those artists once threw down. Like the Robert Altman of McCabe and Mrs. Miller and Nashville and the Hal Ashby of The Last Detail and Bound for Glory, he reckons with the myths that we can’t stop telling ourselves.

In place of Huck and Tom, Mud introduces us to fourteen-year-old best friends Ellis (Tye Sheridan) and Neckbone (Jacob Lofland), and instead of Twain’s St. Petersburg, Missouri, we’re transported to a small Arkansas town, where Ellis lives with his bickering parents (Sarah Paulson and Ray McKinnon) on a houseboat on the Mississippi. One day Neckbone leads Ellis to a remote island, where he has discovered a boat mysteriously lodged in a tree. With a little refurbishing, Neckbone says, they can turn this tree-boat into a secret hideout. Alas, these best-laid plans quickly go awry: it turns out the boat belongs to a fugitive named Mud (McConaughey), who’ll give it to the boys if they’ll help him reunite with his true love, Juniper (Witherspoon).

Like all coming-of-age stories, Mud is essentially about young people waking up to the realities of the grown-up world—and trying to hold true to their pure-hearted ideals regardless. But Ellis and Neckbone don’t simply have to face off against the vengeance-seeking thugs chasing after Mud. They’re also forced to make sense of an entire social order that is crumbling around them. After years of earning his living as a fisherman, Ellis’s father has realized that the shifting economics of the business have made it impossible to carry on. Across the river, meanwhile, lives a secretive fellow named Tom Blankenship (Sam Shepard), who has ended up there because it’s one of the few places left in America for a man who yearns to disappear from society. But Tom’s sanctuary will soon be threatened; in this day and age, Nichols reminds us, you can run but you can’t hide.

Working again with his gifted cinematographer, Adam Stone, Nichols finds the perfect visual expression for this story of irrevocable decline. We see none of the “graceful curves, reflected images, woody heights, soft distances” that Twain mythologized in Life on the Mississippi; instead, the river in Mud is a flat, swampy green or a lonely, desolate expanse of murky blue, where the only signs of life are the poisonous snakes that slither through the waters. Just as affecting are the shots of Ellis riding into town in the back of his father’s pickup truck, on twilit highways banded on both sides by gas stations and chain supermarkets. This stretch of Arkansas could be Kansas or Colorado or Massachusetts or Florida—the specificity of so much of America has long since been lost.

When it premiered last year at Cannes, Mud took some lumps from critics, and they weren’t necessarily off base: a couple of the subplots, involving Neckbone’s oyster-diving uncle (Michael Shannon) and Ellis’s romance with a classmate (Bonnie Sturdivant), go nowhere; the syrupy ending feels tacked on. Playing a white-trash belle burning with desire, the usually hyper-controlled Witherspoon pushes a little too preposterously outside her comfort zone. On the other hand, a European festival may have been the wrong place to launch a movie that so expertly considers and subverts American iconography.

There’s something ingenious, for instance, about the casting of McConaughey—a onetime boy-next-door type who has nonetheless always seemed a bit shady. McConaughey doesn’t venture into the spectacularly weird territory he visited in last year’s Killer Joe and The Paperboy (a vastly underrated thriller that climaxed with the actor hog-tied and naked). But his performance here functions as the melancholy flip side to his terrific turn as the sleazeball stripper in Magic Mike: he vividly captures the desperation of the easy-does-it good ol’ guy who has come upon hard times. McConaughey is neatly paired with two more boys next door, Sheridan and Lofland, whose no-nonsense speech patterns feel entirely contemporary and whose sandy-haired, round-faced looks are utterly timeless. (It’s probably no accident that they closely resemble River Phoenix and Wil Wheaton in Stand by Me, another classic coming-of-age story.)

So where does Jeff Nichols go from here? His next announced project is a sci-fi action chase movie titled Midnight Special. But at this point I can’t be the only one hoping that Nichols—who moved to Austin in 2002 and, save for a few stretches back in Little Rock, has lived there ever since—tackles a Texas-set tale. A state that has always considered itself both central to the American story and somewhat apart from it would seem to be well suited to his sensibilities. The good news is that Nichols, at just 34, has plenty of time to turn his attention closer to home. For now, though, Texas gets to claim this hugely promising director as one of its own. In just three outings, he’s offered up a new and challenging set of answers to the question of what it might mean to be all-American.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Film

- Matthew McConaughey