As a child raised in the Children of God cult, Lauren Hough followed her parents across the globe, from Switzerland to Germany to Ecuador to Texas. She describes herself as a “cult baby,” a closeted lesbian in a conservative Catholic high school in Amarillo, and then a member of the Air Force. Hough also worked as a bouncer at a gay club, paid the bills as a cable tech (an experience she wrote about in a 2018 essay that went viral), and endured periods of homelessness.

To survive, as Hough writes in her debut collection of essays, Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing, she spent much of her life hiding behind lies. One of these fibs, for instance, involved Hough telling people her parents were missionaries instead of saying they were in a cult, or using the name Ouiser Boudreaux (Shirley MacLaine’s prickly character in Steel Magnolias) as her alias when she visited a gay bar so that no one in the Air Force would learn her secret. “I’d learned to survive by becoming what they wanted me to be, as best I could,” Hough writes. “And when I couldn’t, I hid, erasing those parts of me that offended.”

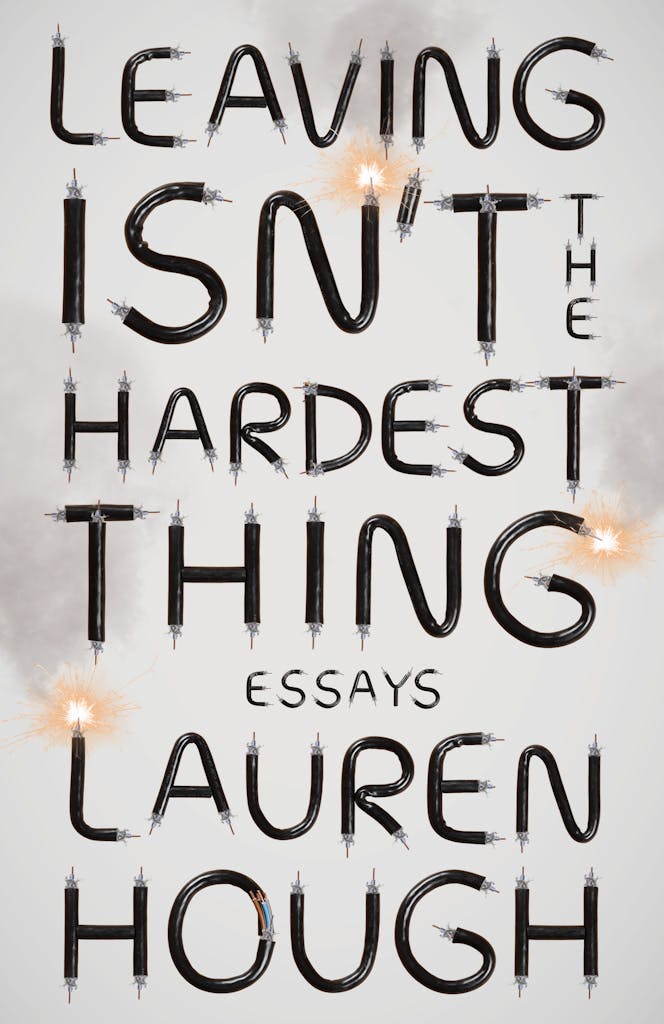

The book, out April 13 via Penguin Random House, sees Hough wrestling at once with the lies she told throughout her life and the fear that underpinned them, with essays that are by turns funny and vulnerable. She writes about her years living with the Children of God, about the trauma of experiencing hate crimes and sexual assault in the cult and later in the military, about poverty and work and love and drugs, and, ultimately, the meaning of home. Through these stories, Hough captures the simultaneous hope and heartbreak of what it means to live in America today.

As Hough writes in the book, Texas remains a special, if complicated, place for her. It’s where her grandmother lived, it’s where her mother returned when she needed to go home, and it’s where Hough herself later moved. As she tells it, Texas has since become a place where she can finally be herself. Hough spoke with Texas Monthly about her deep roots in Texas, growing up in a cult, and writing her book in and around Austin.

Texas Monthly: You wrote your book during the last few years of Trump’s presidency. Did divisions in the country and the political climate influence your writing process at all?

Lauren Hough: It would be impossible to not think about it all. I don’t think I’m alone in thinking that the whole regime just brought up a lot of things we’ve been holding on to for years, especially as women. I was also watching half of our country slide into some sort of weird cult where they think Obama is eating babies.

TM: I wanted to ask you about that, because the word “cult” has been thrown around a lot over the last year or so. I’m wondering, from your perspective, since you experienced an actual cult, whether that comparison is valid, or if we need new metaphors?

LH: I’ve gone back and forth. I don’t want to dilute the experience of living in a cult, but I think it’s an apt comparison. QAnon is most certainly a cult. My journey started with me being like, “You don’t even know what a cult is; I’ll tell you about a cult.” But then when you think about the kids raised in cults and about their information being so completely controlled by their parents, I think QAnon families are like little mini cult families.

TM: You were living back in Texas when you wrote the book, right?

LH: I was in Austin. I was working at a bar called the Iron Bear when my cable guy essay came out and kind of blew up, and then I had to quit that job so I’d have time to write the book. I did a lot of writing sitting at Radio Coffee or Once Over Coffee.

TM: Your family tree goes way back in Texas and your parents each spent time at the Children of God “Soul Clinic” compound near Thurber, which you write about visiting in the book. You’ve had a love/hate relationship with the state over the years, but in the book you reveal that on that road trip to Thurber you were “absurdly happy” to be called a Texan. Do you consider yourself a Texan more than any other place you’ve lived?

LH: I think I do now. I didn’t realize it until I moved back to Austin about five years ago. Now the accent has come back and it won’t go away, which I think is great. I’ve been living on Cape Cod for months, though, and I should be dropping “r’s” and I’m not. But I’m also not really socializing.

TM: What made you leave Austin?

LH: My dog was getting old and I was stuck in my apartment in Austin because of COVID. Everything that was fun about Austin was closed. It was ninety degrees at ten o’clock at night and the only thing my dog enjoyed anymore was walking, so I moved [to Cape Cod] so he could take a few walks on a beach in the cold and enjoy his days. Texas is the first place I’ve missed. I miss everything about it. I miss tacos and I miss people who understand irony. Texas might be the one place in America that I don’t have to explain that it was a joke. You don’t have to add “lol” to the end of every sentence. You can just be sardonic and it’s fine. They get it. I think for better or worse, I am a Texan.

TM: Do you think the culture of Texas shaped your sense of humor?

LH: I do think I developed a lot of my sense of humor in Texas. I don’t know what it is about Texans and what made them the way they are, but strangely Texas has a lot of German immigrants and Germany is the other place where I don’t have to explain that it was a joke. I think a lot of my humor also comes from my mother.

TM: Your mom’s family has deep roots in the state, and your dad spent time here also?

LH: My parents met in England, but they had spent time on the same ranch in Texas. My grandparents were all dirt farmers from Amarillo or the area around Amarillo. My great-grandmother came out here on a covered wagon.

TM: You write about your maternal grandmother often in the book, and the positive influence she had on you. She sounded like such a sweet lady. She was one of the few people who fully supported and accepted you growing up. What do you think she’d think of the book?

LH: She’d love it, I hope. She’d be proud as hell that I got a book published. She was never one for holding back anything. You called her a “sweet lady,” but very few people would describe her as such. A “battle-ax” might be a better term for her. I wish I could tell her about the book. She was sweet to me, in her strange way.

TM: Your book is about hiding who you are and hiding your identity for much of your early life, so what was it like writing these essays that are so deeply personal?

I don’t think I would have written anything if I’d been thinking about who was going to read it. I sort of developed tunnel vision, like I was writing in a diary for me or my agent. Now there’s a very definite imbalance of information that people have when I meet them, like I’m learning your name and where you’re from and you want to ask about the cult or the military or someone I dated. I don’t know what to do with that now. I’m learning as I go and I’m still working that out. It’s a little bizarre.

TM: You’ve said that you’ve gotten in touch with a lot of others who were raised in and eventually left the Children of God. Can you talk about leaving? What that was like?

LH: People don’t leave a cult because they change their minds or even because prophecy keeps failing. They leave because it’s uncomfortable for them personally or they see something they want more. In my leaving a cult, there were times where I thought, “What if they were right and I actually am going to hell? What if the rapture does happen?” But I really liked rock music and junk food and being able to leave the house without permission and a buddy. Those little things in people’s personal lives are what matters more than anything.

TM: A few months ago you tweeted, “My single goal is for my book to become a red flag, a dyke Chuck Palahniuk if you will.” Can you talk about that, and your hopes for the book?

LH: Well, I smoke a lot of pot. It’s legal up here and edibles are fun, and then you tweet on them. I do hope the book helps a few people recognize their own lives in it, and I hope it calls BS on any of the gaslighting that happens about abuse. I hope people can take courage from it.

TM: What are you working on next?

LH: I’ve been trying to write. The writing process is such crap. I hate it. I hate writing. If this book makes enough money, I’ll never write again. I hate everything about it except that one moment where everything is working and you’re like, “This is good as shit,” but that’s like thirty seconds in a year. It’s a terrible addiction. I don’t think it’s healthy to think about yourself this much. As soon as I forget how hard it was to write a book, I might be able to write again. I am working on something about dogs [Hough’s dog died over the winter], but I don’t know how to do it without making it sentimental or cheesy or cheap. Right now it’s a bunch of paragraphs that don’t lead to another paragraph, and sentences that don’t lead to second sentences. That’s a fun phase.

TM: Since you came back and left again, how do you think Texas culture has changed since you were living in the Panhandle as a kid and a teenager?

LH: I think it has changed a lot for the better. There are always going to be die-hard Texans, and Austin itself is a mini cult within a cult. I thought I would be scared as a very lesbian-looking lesbian. Texans are effing weird, though. They have terrible politics, and they’re really nice people. I’ve never figured out how to reconcile that they vote for the worst people and things, but if your car breaks down on the side of the road you’ll have four of them in a pickup show up to help you.

TM: Do you think you’ll move back?

LH: I’ll come back. I miss it so much. I miss Austin. I don’t miss the heat at all, but New Englanders don’t season their food at all. Everything is just deep-fried or boiled to death. I miss Texas. God help me, I do. Turns out that might be home.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Books