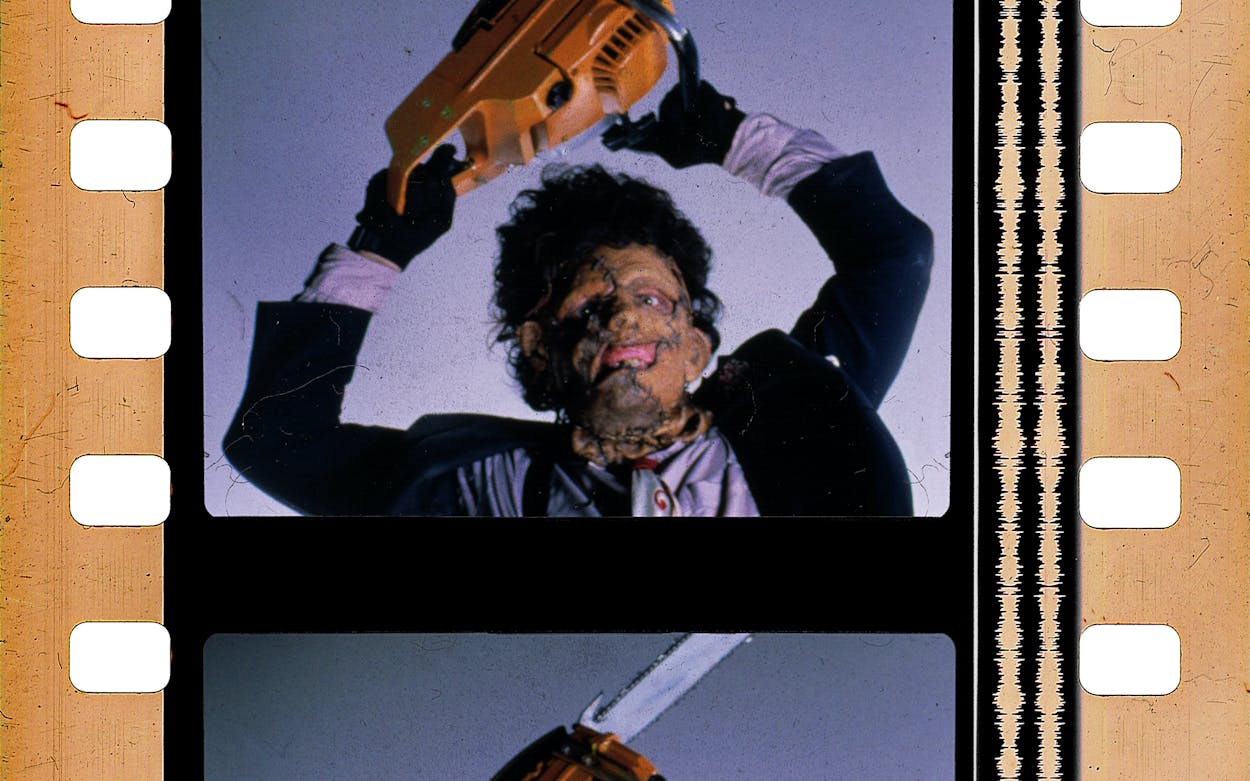

The Chain Saw Massacre might have been a perfectly fine title. It’s blunt and to the point, economical yet evocative. But it’s the “Texas” that really makes it sing. Setting the 1974 film here, in the state that has long stood in for the fading American frontier on-screen, provided an added mythic dimension to the movie’s tale of homicidal cannibals. Austin director Tobe Hooper, after all, wasn’t out to tell a story about Texas, specifically, but about a nation that was spiraling in the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, its institutions on the verge of collapse. Leatherface and the rest of his demented clan were Texans, but, more broadly, they were members of America’s endangered rural class—former slaughterhouse workers whose jobs had been replaced by machines. In this they were kin to countless cattlemen, farmers, and other adherents to the Old Ways who had found themselves cut adrift in the age of industrial capitalism, if they were never quite driven to murder a bunch of doofus hippies about it.

These themes might have resonated just as loudly if the film had been set in, say, the North Carolina hinterlands. But it was Texas—or rather the idea of Texas, enshrined on-screen and in the national imagination as an untamed wilderness populated by “rugged individualists” and other violence-prone misanthropes—that gave The Texas Chain Saw Massacre its terrifying ring of plausibility. Hooper and his coscreenwriter, Kim Henkel, even tried passing the film off as a true story, and while their script did draw some from the real-life exploits of murderer Ed Gein (a Wisconsinite, for the record), as well as from the Houston-based serial killer Elmer Wayne Henley, their ruse mostly relied on that venerable perception of Texas as the sort of place where these kinds of horrors could happen.

Nevertheless, there was nothing explicitly “Texas” about The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. (And as long as we’re poking holes, the movie’s four murders—just one of which was by chain saw—only technically qualified as a “massacre.”) But that all changed with Hooper’s 1986 sequel, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, in which the “Texas” in the title at last carried its own, equally ominous weight. If the original film made Texas complicit by default, suggesting that the state was simply so big and uncivilized that there very well could be backwoods bogeymen lurking along its more godforsaken stretches of highway, then The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 indicts Texas directly. In this movie, the entire state is a threat. It’s a 268,000-square-mile lunatic asylum where everyone, almost to a person, is batsh-t crazy.

The opening scenes pick up with a couple of Austin frat boys driving a Mercedes plastered with a “NATIVE TEXAN” sticker, downing Shiners and whooping it up on their way to the Texas-OU game. (The film’s first line of dialogue is “Hook ’em, Horns, baby!”) They pass the time by plugging road signs with a revolver fired willy-nilly out the window, and they play chicken with a truck that they then run off the road. They also call up and harass rock radio DJ Vanita “Stretch” Brock (Caroline Williams), who, aided by her good ol’ boy assistant, L.G. (Lou Perryman), just happens to record the moment when that same truck suddenly doubles back on the boys and Leatherface (Bill Johnson) pops out of its bed to slice them up good.

Such a gruesome public slaughter would surely kick off a statewide manhunt, you would think, except it turns out that, in Hooper’s Texas, the cops are only nominally in control. The film’s opening narration and text, maintaining the original’s “based on a true story” ploy, catches us up on the dozen years since we last saw Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) make her narrow escape from Leatherface, and it’s here we learn that Texas police spent “a month”—a whole month!—investigating Sally’s story before throwing in the towel. In fact, despite persistent reports of “bizarre, grisly chainsaw mass-murders” across the state, the authorities have officially decided to just sort of . . . ignore them. So when Dallas detectives happen upon the wrecked Mercedes, whose driver’s head has been sawed clean in half, they are quick to dismiss it as just “a couple of wild punks out raising hell.” All of them, that is, except for Lieutenant Boude “Lefty” Enright (Dennis Hopper), a retired Texas Ranger who also happens to be Sally’s uncle.

Lefty’s an old-fashioned cowboy; we know this not only because he wears a big, white Stetson, but because the other cops derisively call him “Cowboy.” Despite their jibes, and against the apparent apathy of his superiors, this lone Ranger remains determined to find the chain saw–wielding cannibals who terrorized his kin and exact revenge. Lefty is a pure and righteous man, given to quoting Bible verses and assuring everyone who doubts him that God is firmly on his side. He is also clearly out of his g—damn mind. This is established early on by what may be the greatest scene in the whole Chainsaw Massacre franchise, in which Lefty pays a visit to a local hardware store, then proceeds to slash the hell out of some logs.

In order for Lefty to get within chainsawing distance of Leatherface’s family—who are here, for the first time, given the wink-wink surname of Sawyer—he uses Stretch as bait, coaxing her into playing the recording of the two boys’ murders during her radio show until it draws their killers out of hiding. Lefty’s reckless-endangerment scheme works: Stretch soon finds herself a captive in the home of Leatherface; his PTSD-suffering Vietnam vet brother, Chop-Top (Bill Moseley); and their daddy, Drayton (Jim Siedow, reprising his role from the original). The stage is thus set for a final, bloody showdown inside the Sawyers’ lair, which lies beneath the ruins of an old amusement park themed around famous Texas battles.

“To make a sequel you have to reinvigorate that original spark,” the film’s screenwriter, L. M. “Kit” Carson, told Texas Monthly in 2002, “which in this case was to go back and punch the button labeled ‘Outrageous.’ ” The first Chain Saw Massacre had been more of an art house thriller—a sort of Antonioni at the abattoir that thrived on stark atmospherics and slowly mounting dread. But the film also had an ironic humor that Hooper, for one, felt had gone overlooked. There would be no such fooling around with subtlety this time. Hooper and Carson envisioned The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 as a big, broad satire for an era of excess, awash in cartoonish gore and mordant, Tales from the Crypt–esque puns.

The film’s subtext was likewise pitched to the rafters. Reinforcing years of feminist critiques, this time Leatherface’s tormenting of Stretch is unmistakably sexual, its undertones spelled out by a scene in which he gently probes at Stretch’s crotch with the phallic end of his chain saw. The character of Lefty is a half-cocked perversion of the classic white hat hero, a 1950s cowboy who runs around the Sawyers’ skeleton-strewn caverns, hacking away at the buttresses beneath those Texas history tableaus and screaming “Bring it all down!” When he tears into a mural of Davy Crockett at the Alamo, the wall suddenly bursts and gives way to an avalanche of gristle and guts. Texas—and therefore America—is built on a bedrock of violence, the film seems to scream. And that blood in our soil has seeped into the groundwater, finally poisoning us all.

In The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, this insanity is no longer limited to an alienated few in the rural exurbs. It’s right out in the open, spreading statewide to the point where a college football game has the cops anticipating Dallas going “blood crazy” with riots. It has likewise infected Lefty’s avenging angel lawman, who represents a more respectable, neoconservative kind of derangement—a Moral Majority nutter who declares himself “Lord of the Harvest” and sets about gleefully dismantling the Sawyers’ lair while he sings “Bringing in the Sheaves.” Even Drayton Sawyer isn’t hiding in the wilderness anymore. He’s become a clout-chasing urbanite, a polo shirt–wearing member of Dallas’s striver class who, as he skins its people to make his human barbecue, also rants about property taxes and the plight of the small businessman.

Whereas the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre offered a macabre critique of a nation at risk of losing its soul, its sequel picks up in an America that has already sold it to the highest bidder. Here, arguably even more than in its predecessor, Texas makes for an especially potent metaphor. At the time of the film’s release, in 1986, the TV show Dallas was entering its tenth season, and it was a cultural institution that had made both its namesake city and the surrounding state synonymous with dog-eat-dog capitalism. Ronald Reagan, although not a Texan, had nevertheless siphoned off some of its brio with his “man on a horse” rhetoric, leaning into his own movie cowboy image by cosplaying at his ranch outside Santa Barbara. Arguably, Reagan had taken the Oval Office only because, despite thousands of write-in votes, Americans couldn’t elect J. R. Ewing himself.

These swaggering cowboy capitalists were everywhere in the mid-eighties, and certainly all over Texas, whose residents had been irrevocably swept up in Reagan’s promises of a new prosperity. As Carson told the Guardian, he had even found his original spark of inspiration for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 during a trip to Dallas’s Galleria, where he’d watched “yuppies buying piles of things, seven sweaters at a time.” Carson figured that, much as the audiences of the seventies had thrilled at watching a bunch of drippy flower children get chewed up by this harsh American underworld they’d blissfully ignored, eighties audiences would get a kick out of seeing myriad Biffs and Buffys butchered by the callous realities created by their endless self-gratification.

Of course, a lot of that yuppie slaughtering was itself killed off in the film’s notoriously brutal editing process, including a deleted scene in which the Sawyers lure a crowd of preppies into their van with the promise of croissants. Still, the film’s broader satirical outlines remained, sketching out a Texas—and thus a Western world—that had gone bonkers with greed, its cycle of conspicuous consumption having led, inevitably, to people eating one another. Again, it was a story that might have taken place in any American city at the time. But because it was in Texas, it cut that much closer to the bone.

Most “Texan” Scene

For a movie that kicks off with a guy firing a bullet into a sign proclaiming “Re-Fight [the] Battle of San Jacinto,” and one in which the bottles of Big Red are so prominent that they practically earn their SAG cards, it’s hard to narrow The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 down to one quintessentially “Texan” moment. Still, for pure symbolism’s sake, I’d give the edge to the Texas-OU chili cook-off scene, in which the madman turned mogul Drayton looks out at a Dallas honky-tonk full of locals enjoying hot, heaping bowls of their fellow man and exclaims, “This town loves prime meat!”

Most “Texan” Dialogue

Likewise, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is awash in lampshaded Texan dialogue, using the word “Texas” at least a dozen times, name-dropping Texas cities from Waco to Burkburnett, and even using the line “Remember the Alamo, cowboy!” But all these callouts pale beside what is arguably the most “Texan” death scene in horror movie history, that of Stretch’s faithful assistant, L.G., played by the late Lou Perryman (billed here as Lou Perry), one of our most authentically Texan actors. Stubbornly refusing to die even after being clobbered repeatedly with a hammer and having his face and most of his torso carved off, L.G. finally kicks off by lying down and exhaling, with all the bone weariness he can muster, with a resigned “Aww sheeeit” worthy of being engraved on the Capitol.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Film & TV

- Movies

- Dallas