In choosing a name for their new literary press, A Strange Object, Callie Collins and Jill Meyers turned to a quotation from an early Donald Barthelme short story, “Florence Green Is 81.” In the story, a character describes the aim of literature as “the creation of a strange object covered in fur which breaks your heart.”

It’s a quotation that seems especially resonant, now that many in the publishing industry wonder if physical books are an endangered species.

“I think books are becoming an increasingly strange object in the same way vinyl records are now strange objects,” said Collins.

“We believe in the subtle art of subtraction,” added Meyers. “Publishing fewer titles, but very fine ones.”

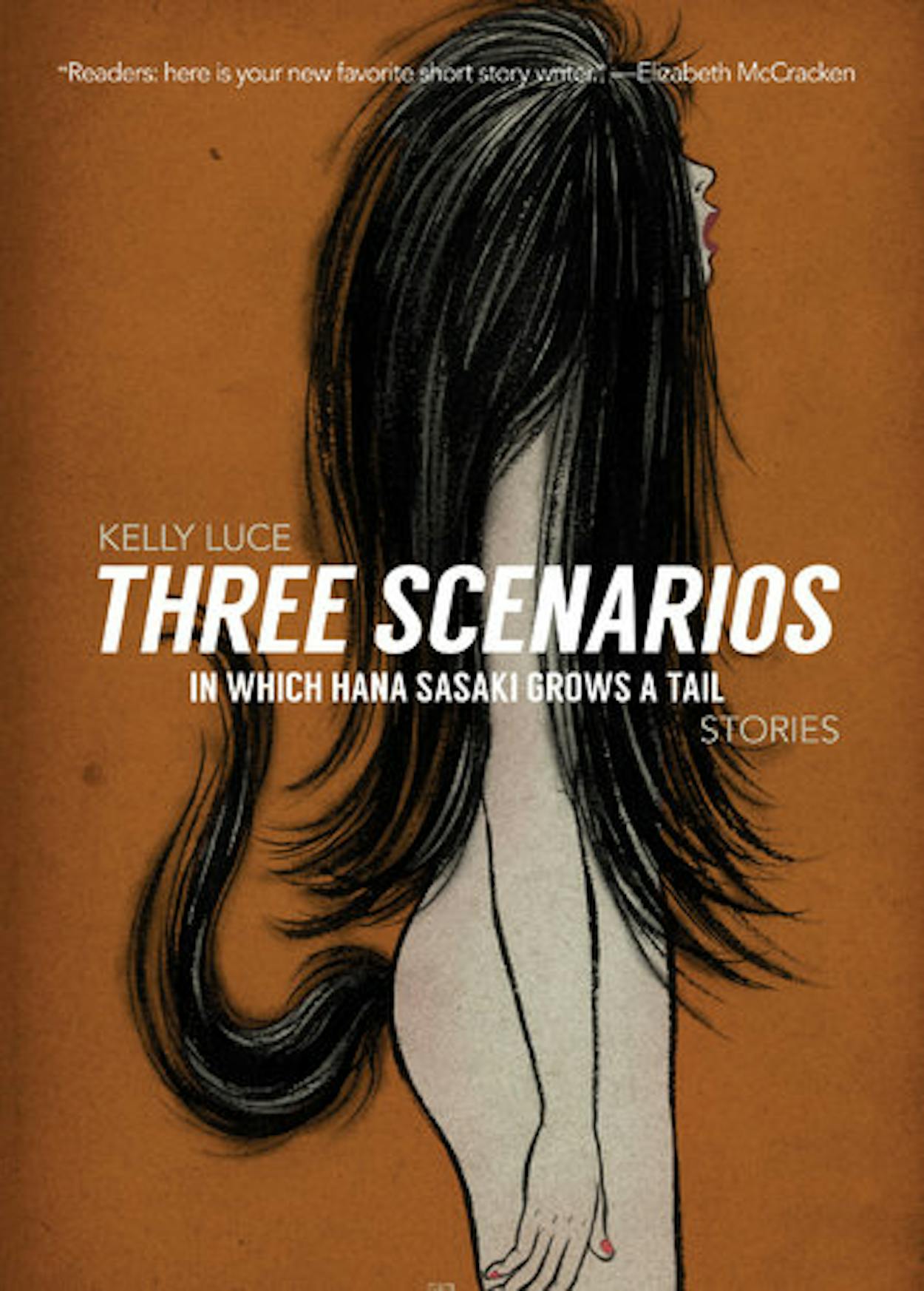

The first title from the press, “Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail,” a debut short-story collection by Kelly Luce, was published in October.

These are not supposed to be healthy times for book publishers. In 2012, Nielsen BookScan reported that overall book sales in the United States were down 9.3 percent from 2011. Sales of e-books, once hailed as the industry’s savior, have also slowed recently. And readers of literary fiction have been shown to be more likely to skip pages or stop reading than readers of genre fiction.

But in Austin an intriguing countermovement is afoot, courtesy of small presses like A Strange Object, as well as a number of new literary magazines. In November 2012, the journal Foxing Quarterly, which includes poetry, fiction and comics, was introduced with the help of Kickstarter funds, after establishing a community presence through a series of concerts and readings. The annual journal Unstuck will publish its third issue in February, and the biannual Synonym, is expected to publish its third issue this month.

Whether Austin will ever rival literary hotbeds like Brooklyn and San Francisco remains an open question. And whether the trend afoot in Texas’ capital simply reflects a national renewal of interest in small presses and literary journals is also open to debate.

“I would say that Austin is beyond burgeoning — it’s already burgeoned,” said Steph Opitz, the literary director of the Texas Book Festival, and the former membership director for the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses in New York. Opitz compared Austin to Minneapolis (where the venerable small presses Graywolf, Milkweed Editions and Coffee House Press have headquarters) and to Portland, Ore. (where Tin House Books is based).

Of course there have also been well-known literary casualties in recent years, including the San Francisco-based publisher MacAdam/Cage, which never recovered from the recession and whose founder, David Poindexter, died earlier this year, and the New York-based journal Open City, which closed in 2011, after 20 years of publication.

Meyers, 37, and Collins, 25, first met when they both worked for American Short Fiction, an Austin-based literary magazine. When Badgerdog Literary Publishing, the nonprofit that published American Short Fiction, closed in 2012, Collins and Meyer decided to create their own commercial press, using money from personal savings and from selling subscriptions to the press’s first few books. (American Short Fiction continues to be published by American Short Fiction Inc., a new, pending nonprofit.) After reaching out to writers whose work they knew, they received many submissions, before ultimately settling on Luce’s manuscript last December.

Luce — who is currently a master of fine arts candidate at the University of Texas Michener Center for Writers — said she was not particularly worried about placing her first book with a start-up press.

“It crossed my mind that it might be a risk,” she said, “but I knew they would make a beautiful object and that they would edit it beautifully.”

Luce’s advance was “significantly higher” than the $1,000 usually paid by small presses. The initial print run for “Three Scenarios in Which Hana Sasaki Grows a Tail” was approximately 1,500, which is about average for a small press. Collins said that sales had exceeded expectations and that the book had received a number of favorable reviews beyond Austin, from major newspapers including The Chicago Tribune and The San Francisco Chronicle.

Still, the company’s leaders are well aware of the financial perils of independent publishing, even in a supportive enclave like Austin. Collins and Meyers plan to publish just three books in 2014, including “Misadventure,” a short story collection by Nicholas Grider, due in February. It will also have a print run of about 1,500.

It is not yet clear whether this emerging Austin literary scene is considerable enough to have an impact on the national culture. Meyers acknowledged the possibility that literary Austin could become a kind of echo chamber that generated little excitement outside its small community of self-selecting readers and writers.

But Collins contended that independent publishers like A Strange Object provided a needed service to serious readers.

“In this really information-heavy era, the filter of a publishing house is becoming increasingly important,” she said. “The major houses have so much pressure to perform well, so literary fiction takes the back seat. I call them gatekeepers but not tastemakers.”

She added, “People are looking more to small presses as the tastemakers.”

- More About:

- Books