Kelvin Sampson is among the greatest college basketball coaches of his generation, but at one point it seemed he might never coach college hoops again. In 2008, while working at Indiana University, he was caught violating recruitment rules and slapped with a five-year coaching ban. He spent his exile as an assistant coach in the NBA.

Sampson got a shot at redemption in 2014, when the University of Houston named him head coach. It was hardly a dream job. The Cougars hadn’t been relevant since the early eighties, when the team—nicknamed Phi Slama Jama for the high-flying play of stars Hakeem Olajuwon and Clyde Drexler—made it to two NCAA championship games. But by the time Sampson took the helm, the program belonged to a minor conference and enjoyed little fan support.

A decade later UH is back. The Cougars have made five straight NCAA tournament appearances, and with backing from board of regents chair Tilman Fertitta—the billionaire restaurateur who attended UH and owns the Houston Rockets—the school completed a $60 million renovation of its basketball arena. And Sampson did all of this at a time when the college game had changed considerably thanks to the advent of a transfer portal, which makes it easier for athletes to switch schools, and the new name, image and likeness (NIL) rules, which allow them to earn money through endorsement deals.

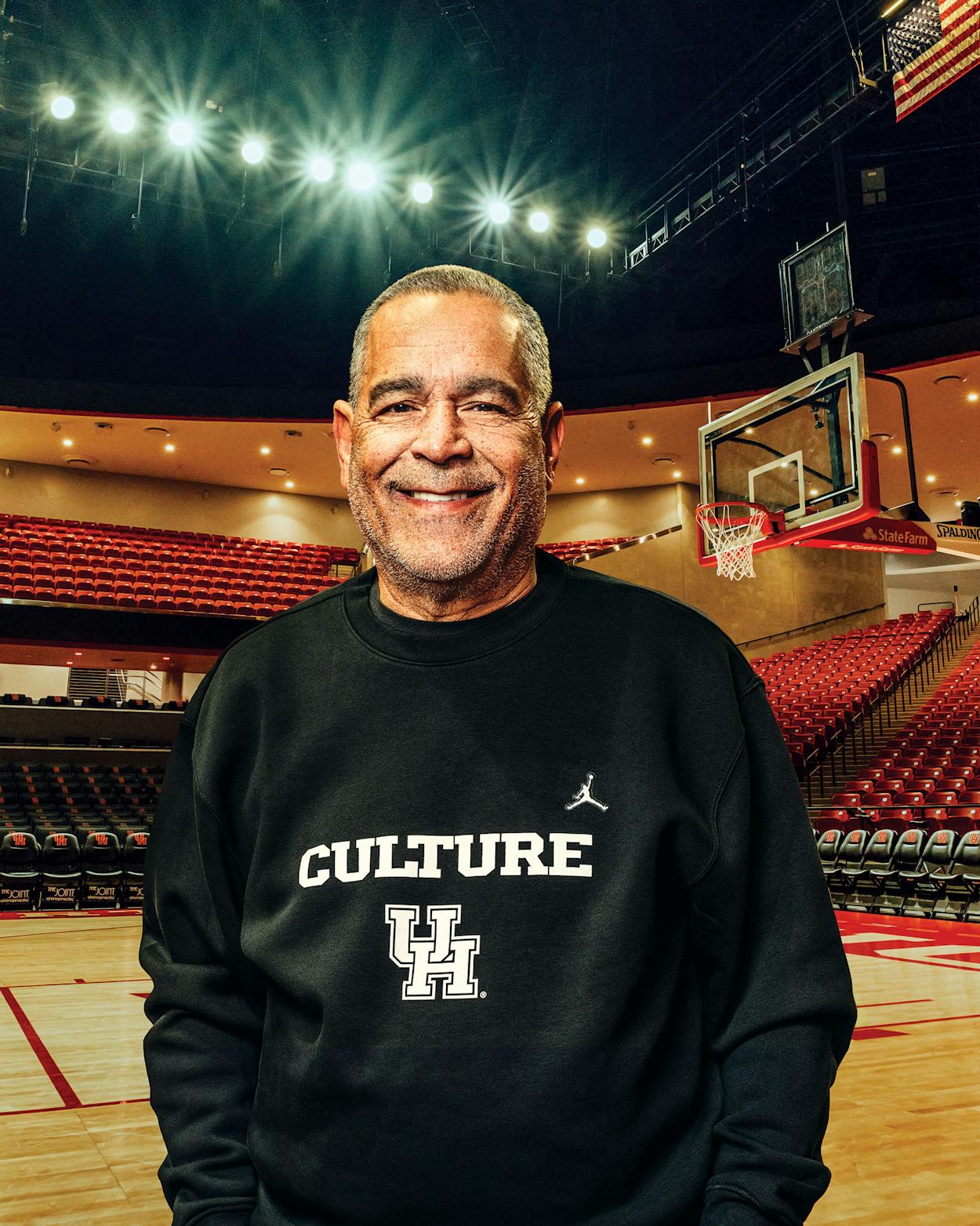

The team’s success under Sampson helped win UH a coveted invitation to the Big 12 Conference, where it made its debut this season. At age 68, Sampson finds himself on top again. About the only thing he hasn’t won is a national championship—which could change this month as the Cougars charge into March Madness.

TEXAS MONTHLY: Many people remember the University of Houston’s famous Phi Slama Jama teams. But from 1985 to 2017 the team didn’t win a single tournament game. What was the program like when you arrived?

Kelvin Sampson: When I came here, we were a school in the middle to bottom of Conference USA. We didn’t have anywhere to practice if it rained, because the Hofheinz Pavilion’s roof leaked. Nobody came to the games. Nobody marketed the games. I was the sixth coach in sixteen years. The kids I’m recruiting have never heard of Phi Slama Jama—their parents don’t know. That’s part of our great tradition. But it has nothing to do with our present.

TM: How did you rebuild?

KS: I had a vision for how I wanted this thing to go, and an administration that shared my vision. I had lunch with Tilman Fertitta, and I told him that I thought you could win a national championship in basketball more easily than in football. In football, the rules are set up to favor the Power Five conferences. In basketball, everybody’s the same. If you make the tournament and win six games, you win. But to do that, you’ve got to have facilities and a coaching staff. Kids don’t sign with schools—they sign with the coach.

TM: What was your pitch?

KS: It was different for every kid. Not everybody is going to play. You have to tell them, “Here’s how I see your first year going.” If you’re a developing player, you’re probably going to sit out your first year. If you’re a kid that I think can come in and start, I tell them that. You have to be courageous enough to tell them the truth. In the decade I’ve been here, we’ve only had three kids in our regular rotation transfer to another school. In this day and age, with the transfer portal, that’s unheard of. And look at the success we’ve had. We have a dozen or so kids playing professionally overseas. We’ve got six playing professional ball in the U.S. right now.

TM: You’ve experienced some setbacks in your career. How much of your motivation in coming to UH was getting back to the top?

KS: I’d been to the Final Four. The top of the mountain. And I thought I could do it here. I thought this place was a gold mine. Look at this city—how in the hell did this program go to crap so fast in this city? You ain’t got to get on a plane to recruit if you don’t want to. It’s a good job, and nobody knew it.

TM: This is UH’s first year in the Big 12. What does that mean to you?

KS: I’m more happy for the school than I am for the program. There was an irrelevance to being in a second-tier conference and an envy about not being with the schools you should be with. Those walls have been knocked down. The role we played in that is gratifying. It’s good for the school, good for [UH president] Renu Khator, good for Tilman, good for our alumni—all the people that love the university.

TM: Let’s talk about the NIL rules. How have they changed your job?

KS: Far more than I could have anticipated. NIL and the transfer portal have taken a lot of our innocence away. The worst thing you could say about a coach when I was coming up was that he buys his players: “He cheats—he buys his players.” Now that’s the only way you can get them. That’s how much things have changed. But you have to adjust. You can’t sit around complaining about it. You put your swimming trunks on, you jump in the deep end, and you start swimming like crazy. Because if we don’t adjust, we’ll fall behind. We’re in a conference with a bunch of sharks. When I got here, we weren’t even a minnow. But now we’re one of the sharks, and we ain’t backing down to none of these people.

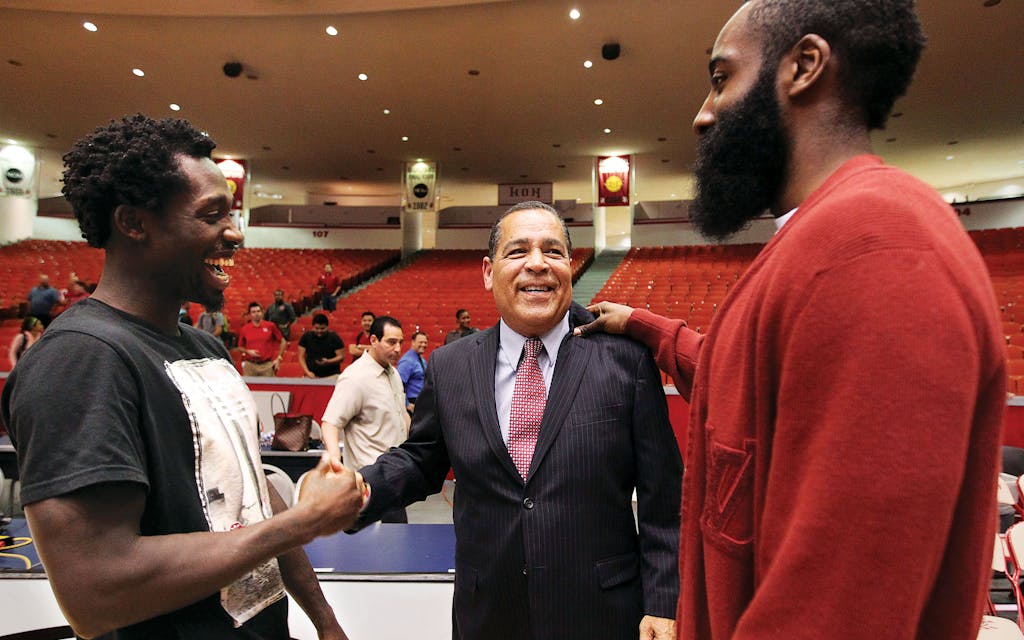

TM: You’ve coached some of the best basketball players of all time: Magic Johnson, Tim Duncan, James Harden. Who is the best player you’ve ever coached?

KS: Magic is the best player I’ve ever been around. It would be a stretch to say I coached him, but I was around him at Michigan State for a season. Back then we called him Earvin. Watching him every day—for me, a little kid out of a country town in North Carolina, sometimes I had to pinch myself. I couldn’t believe I was even there. James Harden—he gets a rap for a lot of things, but never his work ethic. When I was with him, he was one of the hardest workers I’ve ever been around. On game day he would get up two hundred or three hundred shots in the morning, then come back at five o’clock before a seven o’clock game and get up one hundred and fifty or two hundred more. Tim Duncan had the highest basketball IQ, up there with Magic and James. Great players all have work ethic and basketball IQ in common.

TM: You were raised in North Carolina’s Lumbee Native American community. [In 2007 Sampson testified in front of Congress requesting federal recognition for the tribe, noting that without it the Lumbee were “second-class Indians in the eyes of the federal government.”] How has that upbringing affected your approach to coaching?

KS: Growing up, I didn’t have access to a lot of things. None of my grandparents had an eighth-grade education, but they were the hardest workers and most disciplined people I’ve ever been around. My mother worked as a nurse while raising four kids. My dad was a high school basketball coach—he left at six in the morning and got home around eight or nine at night. I was raised with a chip on my shoulder. I’ve never lost it.

TM: As we speak, the AP has you ranked number three in the country. [At press time, the school was ranked fifth.] How do you feel about your chances in the tournament this year?

KS: The media and fans have the luxury of thinking ahead. Every game to me is the most important game of the season, because you can lose it. I don’t ever think past our next game. That’s how you think when you have a chip on your shoulder.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.