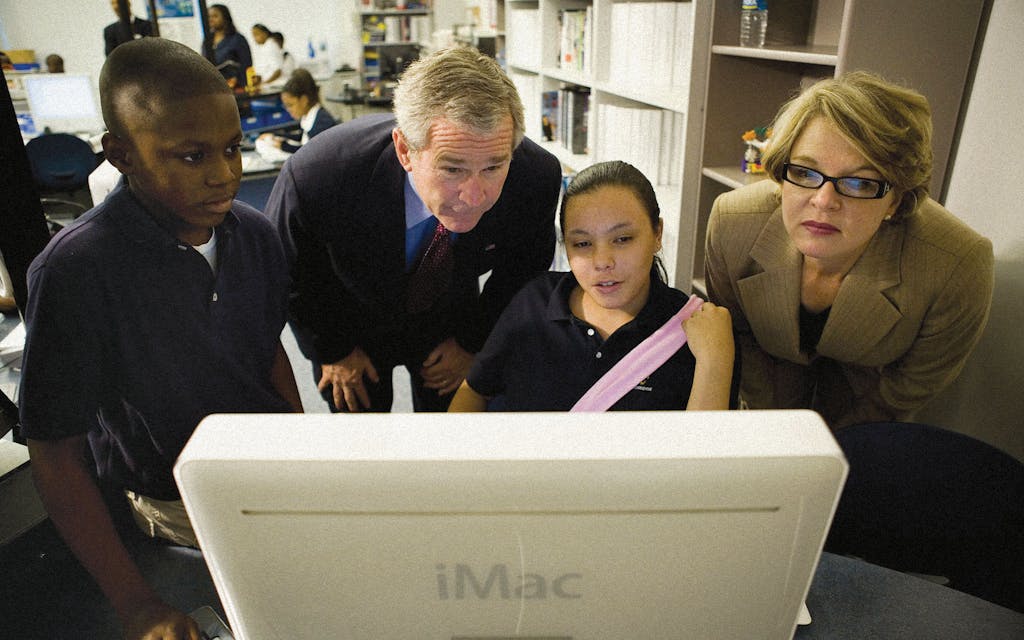

In the early eighties Margaret Spellings, an ambitious University of Houston grad, arrived in Austin to get involved in politics and quickly ended up working on education issues. (“It doesn’t take you too long to figure out that in state government the action is in education,” she once said.) She got a job as a staffer with the House Committee on Public Education and later as a lobbyist for the Texas Association of School Boards. In 1995 she became Governor George W. Bush’s chief education adviser.

When Bush moved on to the presidency, in 2001, Spellings joined the administration as his assistant for domestic policy. She was one of the chief architects of the controversial No Child Left Behind Act, which emphasized standardized tests and significantly expanded the federal government’s role in holding public schools accountable for educating all students, especially low-income and minority children whose achievements trailed those of their peers. From 2005 to 2009 Spellings served as U.S. secretary of education and later as president of the seventeen-campus University of North Carolina System. Then, in 2019, she returned to Texas to head Texas 2036, a nonpartisan think tank that focuses on the most serious issues affecting Texans as the state heads toward its bicentennial, in 2036.

This past summer Spellings resigned from Texas 2036 to return to Washington to lead the not-for-profit Bipartisan Policy Center. Before she left, I asked her what she thought about the state of public education in Texas today. Was it getting any better? Was it getting worse?

Margaret Spellings: We’re slowly, very incrementally and modestly, improving. But more than half our kids still can’t read or do math at a proficient level—a level that’s going to be required in life and in the world of work.

Texas Monthly: In fact, you’ve noted that sixty percent of all Texas public school students aren’t at grade level for math and forty-eight percent aren’t at grade level for reading.

MS: It’s depressing. I used to say if sixty percent of the planes that took off at Love Field didn’t land, or if sixty percent of the lunches in the cafeteria were tainted, people would be outraged.

TM: The No Child Left Behind Act was signed into law in 2002. What essentially did it do?

MS: It was a commitment to equity. It was all about closing the achievement gap and focusing on holding ourselves accountable by testing every kid in reading and in math, reporting that data, and requiring schools and districts to make progress against that goal. And once the law was enacted, we saw some really important gains in student achievement.

TM: So what happened to all that momentum?

MS: Around 2008 came the financial crisis, and that caused states around the country, including Texas, to say, “Well, we’re not going to be able to spend as much on education, so let’s turn down the pressure on student achievement.” We took our foot off the gas pedal. And that is when things started to go in the wrong direction. In 2011 the State of Texas actually lowered funding for education, temporarily.

TM: What bewilders me is that there’s still a lack of funding for education. This year legislators in the state House of Representatives tried to funnel more money to public schools for long-overdue teacher pay raises. But the effort was stifled by Governor Abbott and Republican state senators who want to give vouchers to parents so they can send their kids to private schools. You must have been unhappy about that.

MS: There’s millions of dollars flowing to schools right now—

additional dollars for high-quality instructional materials and school safety. But you’re right, the Legislature didn’t fund a lot of the stuff they should have funded, like increased teacher pay or tutoring technology. What remained undone and is going to be litigated in a special session this fall is a discussion about vouchers and additional requirements for teacher pay.

TM: Governor Abbott, who called the special session, seems intent on passing a voucher plan.

MS: Vouchers aren’t going to be the death knell of education. But they’re not a silver bullet. An eight-thousand-dollar-a-year voucher is not going to get a kid into an elite private school. Most of our kids are going to continue to be educated in our public schools, which is why school accountability is still so important.

TM: I’ve heard you say that in today’s competitive job market, a traditional high school diploma just doesn’t cut it. What do you mean by “cut it”?

MS: A lot of high school graduates aren’t ready for the technically oriented jobs that need to be filled for us to stay prosperous as a state.

TM: In fact, according to Texas 2036’s research, by the year 2036 more than seventy percent of jobs that open up in Texas will require a post–high school credential. But only about one in three of today’s teenagers will have that sort of credential within six years of graduating from high school. That means two out of three will be largely locked out of the workforce.

MS: That’s why I am excited about something the state legislature did this year with $428 million of the nearly $700 million it gives to the state’s two-year community colleges. Community colleges typically have offered a whole lot of what’s called “gen ed” [general education, which consists of basic liberal arts and science and math courses that most students take]. They’ve received the majority of their state funds based on the number of hours students have spent in a classroom, regardless of whether they graduated or transferred to a university. But the new state law sends more money to community colleges where students receive credentials or degrees for jobs that have proven value in the marketplace, such as advanced manufacturing or computer-aided design.

TM: Do you think the money earmarked for community colleges is close to being enough to make significant changes?

MS: We don’t know yet. The jury’s out, but it’s a great start—a super important reform.

TM: How much of an overhaul does public education need?

MS: This idea that we’re all going to congregate from August fifteenth until Memorial Day—that one size fits all—is obsolete. We’re on a journey to a distributed system of education. Education is going to be more à la carte. You’ll see more online charter schools and more pods. [Pods, which began during the COVID-19 lockdowns, are small groups of students—around eight or ten—that meet a few half days a week with a teacher.] We’re going to see more employer apprenticeships. We also should see community college courses being offered to the eleventh and twelfth grades. And we need to make sure that kids are getting high school credit and community college credit for those courses.

TM: After four decades, you must be tired of fighting for better public education.

MS: I understand the frustration that people have about this long, long journey. But transforming an educational system that serves millions is inevitably a long-haul mission, requiring steadfast resilience and unshakable optimism. We cannot sit around and whine and moan about the situation and then not get on the battlefield and fight. You’re part of the problem if you don’t fight.

I have no doubt that Texans can find common ground when future generations and our future economy are at stake.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

This article originally appeared in the November 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “A Former Education Secretary Isn’t Giving Up On Public Schools.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- TM Talks

- Public Schools