“According to my grandmother,” Willie Nelson once said, “the definition of music is anything that’s pleasing to the ear. Once I learned that, I quit thinking about it.”

That’s a perfect Willie quote. It touches on family and music, the two things that matter to him most. Like the songs he’s written, it’s clean, short, and simple on its face, with a dose of his signature everyman humility. Since 1962, Willie has recorded an astounding 143 albums in just about every genre but hip-hop and heavy metal. If you’ve ever wondered why he has ranged so widely, the quote explains it: apparently Willie heard something in the various styles and songs he’s explored that made him feel good. And he never worried about whether that made sense to anyone else; his grandmother told him it didn’t matter.

Willie gave that quote to his friend Turk Pipkin, an Austin author, comedian, and filmmaker who also happens to be—because we are in Willie World now—a onetime professional juggler and the cofounder of a global nonprofit that has built water wells, schools, and libraries in Kenya. The two were playing golf on Willie’s course outside Austin, and Pipkin was on assignment for Texas Monthly, working on a story that would run in a 2003 special issue commemorating Willie’s seventieth birthday.

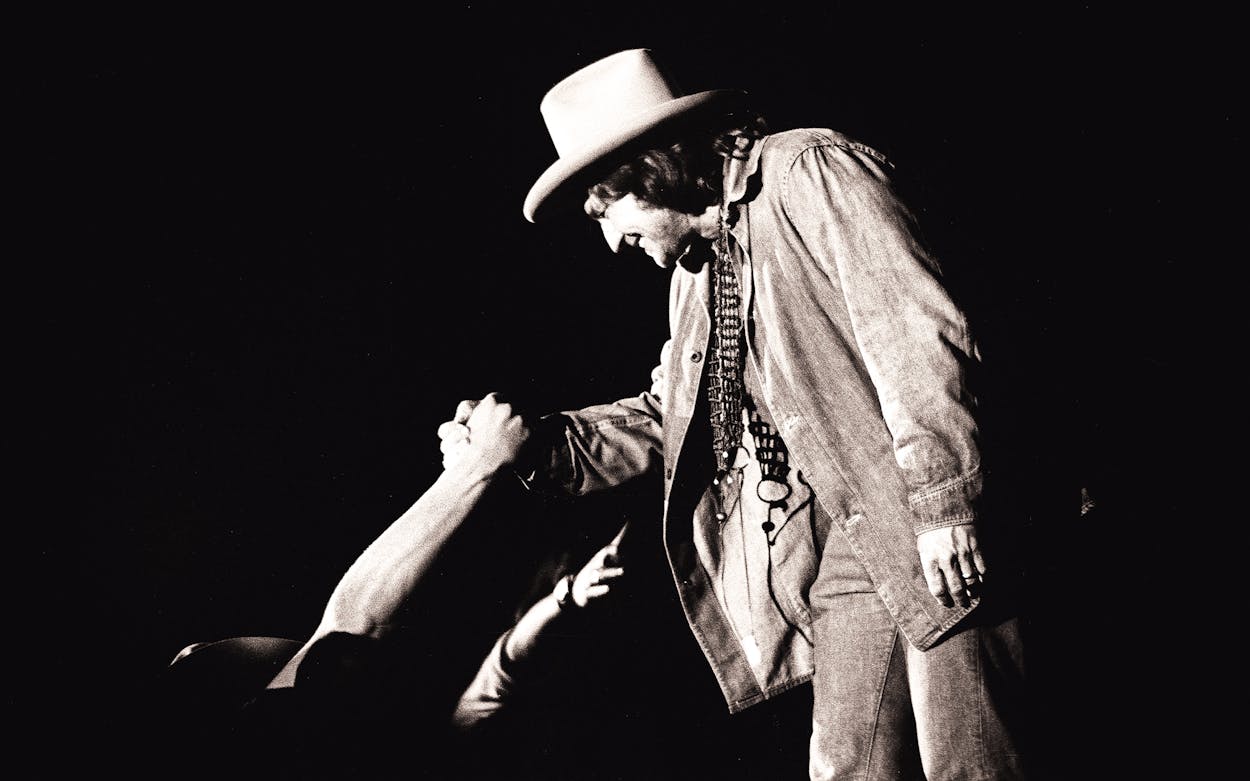

Obviously, it was not the first time Willie had landed in our pages. His first in-depth appearance in Texas Monthly came in the November 1973 issue. The story, “The Coming of Redneck Hip,” was written by Don Roth and Jan Reid, who described one of Willie’s earliest shows at the Armadillo World Headquarters, in Austin. At that point, there was no good reason to expect anyone to be talking about him or the magazine nearly fifty years later. Willie was a forty-year-old singer-songwriter who had written huge hits for others, most notably “Crazy,” for Patsy Cline, and “Hello Walls,” for Faron Young, but had never managed to steer his own career anywhere near stardom. He could reliably pack dance halls and sell records in Texas, but that was about it. And the fact that he’d recently started getting some love from rock critics and grown his audience to include hippie kids in Austin didn’t have to portend anything. He could very well have been setting the stage for a long career as a beloved regional act.

Oh, and Texas Monthly? The issue that contained “Redneck Hip” was just our tenth. Founding publisher Mike Levy was still trying to convince subscribers and advertisers around Texas and the U.S. that he could pull off the statewide equivalent of a city magazine, and a lot of those people were telling him it was a bad idea. They had logic on their side.

But somewhere along the line, Willie became Willie. Fans can argue about when that was. Maybe it was after he moved to Austin and then, finally free of the Music Row industrial complex, delivered the one-two punch of Shotgun Willie and Phases and Stages in 1973 and 1974. Or maybe it was 1975’s Red Headed Stranger, the bare-bones song cycle of revenge and redemption that broke him as a national act. Maybe it was the international superstardom that came in the early eighties with pop hits like “Always on My Mind” (1982) and “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before” (1984), followed by his characteristically understated appearance—in a tracksuit jacket, jeans, and running shoes—in the megastars-only video for the famine-relief anthem “We Are the World” (1985). But whenever it was, over the last half-century, Willie grew from being Texas’s favorite country singer to being one of the most beloved entertainers in the United States, and then in the world. And Texas Monthly has been fortunate enough, owing partly to proximity and mostly to Willie’s openness, to have a bird’s-eye view of the whole, long ride.

No one is having an easy time right now, and Willie has reacted the way he always does: using music to try to bring people together and get money to those who are suffering.

Last summer, some editors at the magazine broached the unthinkable: What do we publish when Willie is gone? It’s a question that media outlets around the world have asked every time he’s canceled a tour date in the past twenty years. But our answer was immediate and resounding: Screw that. We need to celebrate Willie—to thank him—while he’s around.

So we embarked on this special issue. A few of the stories are from our archives, including profiles of Willie from when the wider world was first learning who he was, from when he was famously battling the IRS, and—on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday—at a moment when he was feeling pensive, reflecting on what was already a well-lived life. The majority of the stories, however, are new, such as essays on his singular stature as a songwriter, vocalist, guitarist, and, oddly, landlord. But the most timely of the new pieces is Holly George-Warren’s depiction of Willie as champion of the people. George-Warren describes Willie’s lifetime of good acts, with a focus on his work on behalf of the American farmer. For anyone who has ever conflated Farm Aid’s annual, all-star concerts with the relative frivolity of Willie’s Fourth of July picnics—and let’s face it, the man can throw a party—George-Warren relates the creation story of Willie’s nonprofit, detailing the rural tragedy he was addressing when he founded Farm Aid in 1985. She makes the point that his work has saved not only homesteads and livelihoods but also lives.

That’s a story people need right now. The world is a very different place from the one we were working in when this project started last fall. Between the COVID-19 pandemic and the long-overdue reckoning with systemic racism and police brutality, no one is having an easy time. Willie has reacted the way he always does: using music to try to bring people together and get money to those who are suffering. He has played multiple live-streamed fundraisers from his headquarters in Luck—first to benefit musicians who could no longer play live, and later for nonprofits such as Six Square, which works to preserve Austin’s historically black cultural district.

As events unfolded, our special issue took on a sense of urgency. We’ve learned a lot from Willie over the years, and the biggest lesson became the guiding philosophy for this special issue: When life gets hard, Willie Nelson gives people a song. And Texas Monthly gives people Willie Nelson.

This article originally appeared in the Willie Nelson special issue with the headline “The Willie Way.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Music

- Willie Nelson