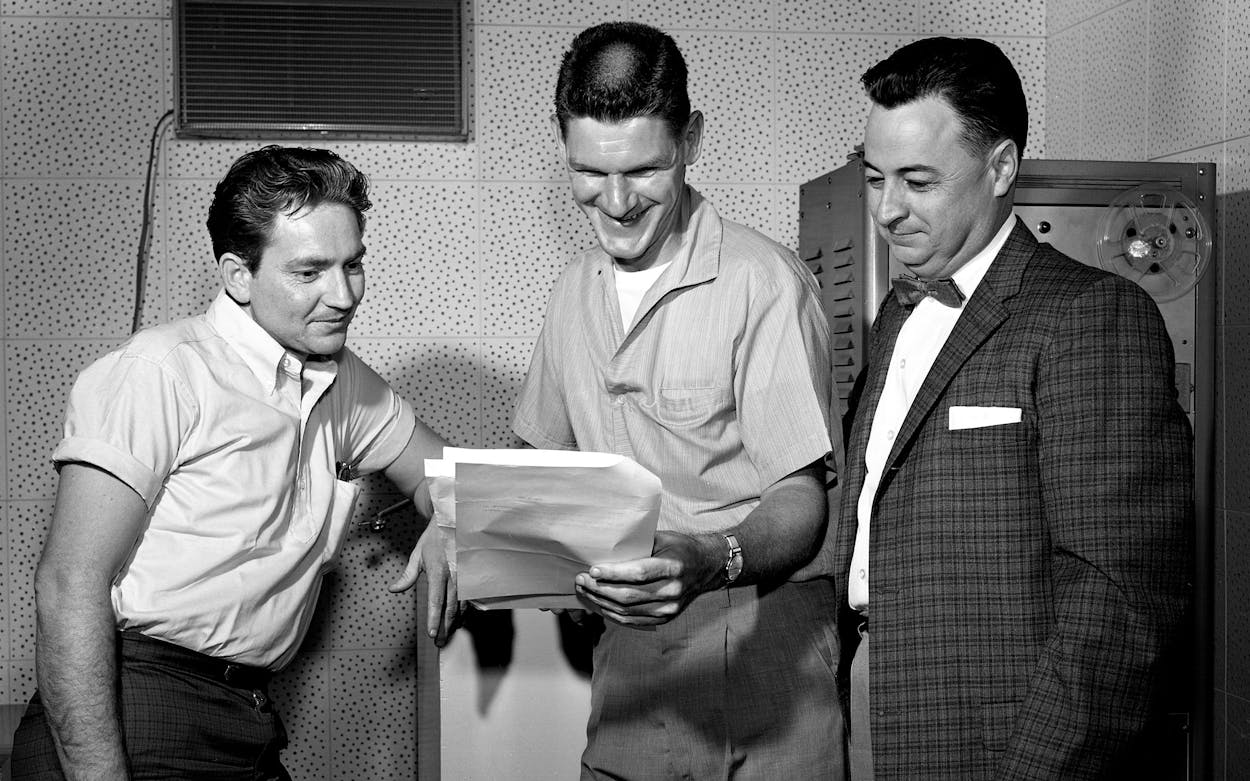

Even hard-core Willie nerds sometimes forget that his spear-tip position in the mid-seventies’ outlaw movement was actually the second time he revolutionized country music. The first came at the dawn of the sixties, when he signed a publishing deal with Ray Price’s Pamper Music company, joining a writing staff that included fellow young-gun composers Harlan Howard and Hank Cochran, both of whom were also recent Nashville transplants.

The three wrote songs that were more sophisticated, both melodically and lyrically, than what had come before—and, arguably, just better—as evinced by Patsy Cline’s two massive pop-crossover hits in 1961, Harlan and Hank’s “I Fall to Pieces” and Willie’s “Crazy.” Those tunes, brought to life by Owen Bradley’s high-polish production, helped set the template for the cosmopolitan Nashville sound that would dominate the decade. And though Willie was the only one of the three writers to become a household name as a performer, the other two would continue penning classics until well into the eighties, including “Why Not Me,” a Harlan cowrite that the Judds took to number one in 1984, and “The Chair,” a Hank cowrite that George Strait rode to the same spot a year later.

For all their collective success though, Harlan, who died in 2002, was the one who became regarded as the greatest country songwriter ever. A Detroit native with Kentucky roots, he fell in love with country music on the Michigan farms where he grew up, deciding early on that he wanted to create those songs himself. Working a day job driving a forklift in Los Angeles in the mid-fifties, he started mailing compositions to Nashville, and once five-figure royalty checks began hitting his mailbox in response, he made the move there in 1960 and signed on with Pamper. There he found near-instant, unprecedented success; at one point in 1961, he had fifteen songs in the country Top 40. Ultimately, he’d write more than four thousand songs, with more than a hundred reaching the country top ten, and as an eager cowriter, mentor, and raconteur, he became one of Nashville’s most beloved figures. His frequent guitar-pull parties were legendary; at perhaps the most consequential one, in late 1972, a struggling Willie played a batch of new songs that were heard by Atlantic Records exec Jerry Wexler, which led to a record deal, Shotgun Willie, Phases and Stages, and the rest of Willie’s career.

Willie repays that favor, and every country fan’s debt, to Harlan with his new album, I Don’t Know a Thing About Love. It’s a tribute to one composer, a tradition that was once a Nashville staple—see George Jones Sings the Songs of Dallas Frazier (1968) and Waylon Sings Ol’ Harlan (1967)—that has essentially been abandoned by every country star but Willie, who previously produced similar celebrations of Lefty Frizzell (1977), Kris Kristofferson (1979), and George Gershwin (2016). The new record also happens to be, according to Texas Monthly’s admittedly unscientific but painstakingly researched math, Willie’s 150th album.

As he has with all but two of his last seventeen albums, Willie worked on the record with producer Buddy Cannon, whose first chore was to come up with a list of potential songs. “I sent him a list of about thirty,” says Cannon. “It took him about five minutes to get back to me and say, ‘Let’s cut the first ten.’ He was good with any of them. They’re all great songs.”

In truth, more thought went into it than that. Willie and Cannon wanted to stay away from obvious choices, especially ones Willie had recorded before, so songs like “Heartaches by the Number” and “I Fall to Pieces” did not make the cut, though other iconic hits did, such as “I’ve Got a Tiger by the Tail,” a signature song of cowriter Buck Owens—and one that Willie had somehow never recorded. The two also chose to resurrect less-recalled weepers such as “She Called Me Baby,” a 1961 composition that Charlie Rich topped the charts with in 1974; “Too Many Rivers,” a top-twenty pop hit for Brenda Lee in 1965 and a top-five country hit for the Forester Sisters in 1987; and “Life Turned Her That Way,” which Mel Tillis took to number eleven on the country charts in 1967 and Ricky Van Shelton topped the same chart with in 1988.

The fact that those songs became hits in multiple eras with markedly different arrangements points to their timelessness. But for these recordings, Willie wanted to place them squarely in a mid-sixties honky-tonk, so instruments like steel guitar and tic-tac bass figure more prominently on Don’t Know a Thing than any major-label Willie release since 1974’s Phases and Stages. There’s also more Trigger on the record than in most recent efforts, presumably because these are songs Willie has known so well for so long. Though at times his picking feels a little low in the mix, it’s easy to appreciate on headphones, especially on “Too Many Rivers” and the title cut. And the Tex-Mex flavor to his fills on “Streets of Baltimore” is vintage Willie.

The lone exception to the old-school country sound is lead single “Busted.” For that one, Willie and Cannon took their cues from another of Willie’s old friends and heroes, Ray Charles, who had a top-five hit with the song in 1963. But to Willie up the new version, Cannon replaced Ray’s horn section with Mickey Raphael’s harmonica, and to edge it closer to country, he had steel guitarist Mike Johnson play the instrumental solo. “I’m pretty sure no one has done that before,” says Cannon.

The result is almost certainly the countriest record that will be released in 2023. “Instead of coming up with something ‘cool and different,’ ” says Cannon, “we really just went back to the way it might have been when Harlan wrote the songs.”

- More About:

- Music

- Willie Nelson

- Austin