Throughout his career, the idea of Woody Harrelson has threatened to eclipse his work. Granted, his off-screen persona as a stoner savant who reels off polemics about industrial hemp in between poker games with Willie Nelson is more intriguing than some of his movie roles. But it’s also easy to underrate Harrelson because his performances feel so unforced. You don’t really see the acting. You just see Woody.

Take Venom: Let There Be Carnage, slated at press time for theatrical release this month, in which Harrelson plays the super-villain Carnage, a.k.a. Cletus Kasady. When Kasady isn’t morphing into a snarling extraterrestrial, he looks and sounds a lot like our notion of Woody Harrelson—the kind of polite yet rascally Southern boy that the actor has embodied since he was entertaining his high school classmates with Elvis impressions. There are moments when Kasady unleashes his psychopathic rage, screaming and punching walls. But Harrelson appears most menacing when he simply crooks his gee-whiz grin and softens his usual laid-back pothead lilt into a creepy singsong.

Harrelson likely will deploy a similar minimalism in HBO’s upcoming limited series The White House Plumbers, in which he plays Watergate conspirator E. Howard Hunt. Early production stills show Harrelson in a suit, looking utterly nondescript—which is apt for a historical figure whose buttoned-down anonymity allowed him to move in the shadows of American intelligence. But at first glance, he doesn’t leap out as someone doing some capital-A acting. Woody just looks like Woody. (By contrast, his costar Justin Theroux is forced to sport a comical walrus mustache for the role of G. Gordon Liddy.)

It’s not that Harrelson doesn’t have range. In fact, he’s one of our most versatile actors, capable of playing manic psychopaths, existentially weary lawmen, and foppish eccentrics with equal conviction. Over the next couple of years, he’s slated to play a Marxist cruise ship captain in Triangle of Sadness (2022), an assassin in the Kevin Hart buddy comedy The Man From Toronto (2022), and a Finnish doctor who tends to the Nazi leader Heinrich Himmler in The Man With the Miraculous Hands (TBD). In these movies, Woody will, again, look and (except, probably, in that Nazi one) even sound an awful lot like Woody. If Harrelson never quite disappears into a role like, say, Christian Bale or Daniel Day-Lewis, then he manages the equally vital trick of making his myriad characters feel like natural extensions of the same man. With apologies to Walt Whitman, he is Woody, and he contains multitudes.

This wasn’t always so apparent. The Midland-born sixty-year-old arrived on television screens in 1985 as Cheers’ Woody Boyd, a role that pigeonholed him early as “the cute idiot,” in part because it seemed he was barely acting. Boyd hailed from Hanover, Indiana, home of Hanover College, Harrelson’s alma mater. Both Woodys were corn-fed church boys. Both radiated a sweet simplicity and a charming indifference to their own sex appeal. Harrelson even occasionally lapsed into his childhood Texan twang during Boyd’s most egregious country rube moments. The two seemed as synonymous as their names.

By the time Cheers wrapped, in 1993, Woody Boyd had made Woody Harrelson a star, garnering him five Emmy nominations and one win, plus a reputation as one of Hollywood’s most eligible lady-killers. Harrelson was so popular, he later told GQ, that an NBC executive tried persuading him to keep Cheers going by having Boyd take over the bar. Harrelson wisely said no.

It was a bold move, considering Harrelson didn’t have many other offers on the table. As he would recall to his friend and fellow Texan Owen Wilson for Interview magazine, “I was on Cheers for eight years, and I couldn’t get another job, and I thought, ‘I’m going to be Woody Boyd forever.’ ” Indeed, Harrelson’s earliest forays into movies were both aided and haunted by Woody Boyd. His first major role, as the basketball hustler Billy Hoyle in 1992’s White Men Can’t Jump, which was a critical and commercial hit, confirmed that Harrelson’s charisma translated to the big screen. But it didn’t reveal new facets of his acting. Hoyle was just a street-smart Boyd, playing up the dopey-hick act to con anybody who underestimated him.

Harrelson tried breaking away from portraying adorable dummies in 1993’s Indecent Proposal, as the tormented young architect who rents out his wife, played by Demi Moore, to Robert Redford’s courtly billionaire. Director Adrian Lyne had wanted Val Kilmer, but after watching White Men Can’t Jump, he was persuaded that Harrelson could be a viable sexual competitor to Redford. The critics were less convinced. Roger Ebert related a friend’s opinion that, given the choice “between being faithful to Woody Harrelson or sinning with Robert Redford, Bob could keep his million and she’d consider it anyway.” Critic Stephen Hunter went for the jugular: “Architect? You wouldn’t trust this boy to find an outhouse, much less design one.”

Harrelson’s next movie lead found him leaning into his dimwitted-Adonis persona in order to subvert it. Oliver Stone cast Harrelson as the serial murderer Mickey Knox in 1994’s Natural Born Killers because, as Stone explains in Matt Zoller Seitz’s The Oliver Stone Experience, he sparked to Harrelson’s “white trash” vibe, a sense of rabid-possum rage lurking beneath that laconic exterior. Harrelson shaved off his floppy man-boy hair and laced his amiable drawl with seduction and malice—Woody Boyd as possessed by Charles Manson. It’s the kind of showy, scorched-earth performance that screams for audiences to take an actor seriously, and suddenly, many did. But unfortunately, whatever momentum Natural Born Killers might have given his career was soon lost to controversy.

Amid the political war brewing over media depictions of violence, Natural Born Killers became an easy scapegoat. Aspiring Republican presidential candidate Bob Dole often cited it, along with rap music, as evidence of the country’s moral decay. Then came a string of copycat murders, committed by some self-avowed fans of the film. One of those murder victims happened to be a friend of author John Grisham, who personally vetoed Harrelson’s casting in the adaptation of his book A Time to Kill. Instead, the star-making role went to a young unknown named Matthew McConaughey.

Given all that fuss, it’s easy to see why Harrelson retreated to 1995’s Money Train. A rollicking, Lethal Weapon–indebted buddy comedy in which he starred opposite his White Men Can’t Jump costar Wesley Snipes probably seemed like a safe bet. But the movie bombed, and Harrelson’s portrayal of a desperate transit cop drowning in gambling debt was widely criticized. “He can be quite charming playing a goofball, a con man or a lovable rogue,” wrote John Petrakis in the Chicago Tribune. “But he has none of the weight necessary to pull off the supposed tragic dimensions.” More controversy came Woody’s way when another copycat, allegedly emulating a scene from Money Train, set a subway booth on fire. For the second time in a year, Bob Dole was lambasting a Woody Harrelson movie; this time, he explicitly called for a boycott of Money Train.

Perhaps sensing his career was getting away from him, Harrelson tried the art-house route by starring in Sunchaser, for the iconoclast filmmaker Michael Cimino. Compressing his airhead allure behind a pair of wire-rimmed glasses, Harrelson played a prissy oncologist who’s kidnapped by one of his patients; the duo sets off on a wild road trip that’s laced with trippy Native American mysticism. But Cimino had become increasingly unstable during production, and upon its premiere at Cannes in the spring of 1996, the film was widely panned as pretentious, even incomprehensible. Sunchaser ended up swiftly going to video, where it promptly disappeared.

By then, Woody Harrelson was one of the most famous names in the world, with a hit TV series and lead roles in several major films to his credit. Yet to most people, and despite his best efforts, he was still just Woody from Cheers. He might have stayed there, were it not for two disparate performances that, in quick succession, finally revealed the breadth of what Harrelson could do.

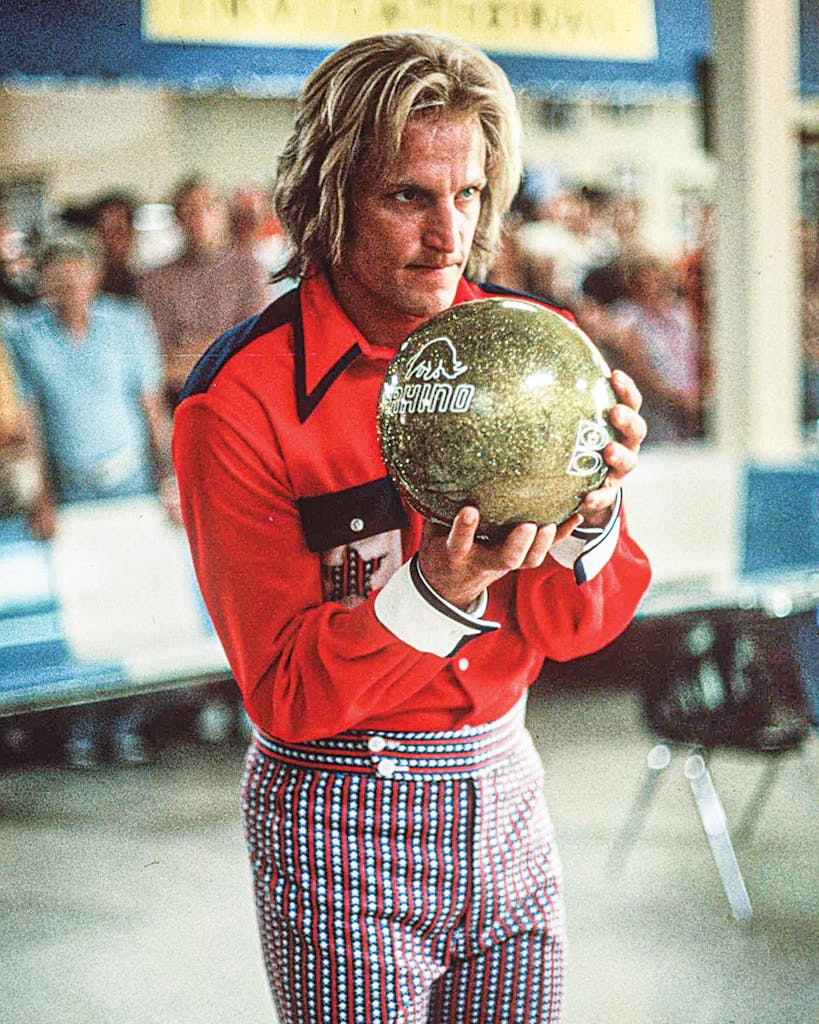

In the summer of 1996, MGM released the bowling comedy Kingpin, starring Harrelson and fellow Texan Randy Quaid. Directed by Peter and Bobby Farrelly as the follow-up to their smash hit Dumb and Dumber, the comedy bears a lot of the duo’s hallmarks: road trips, gross-out gags about toilets and horny old ladies, physical trauma. But it finds an unexpected depth in Harrelson’s wastrel protagonist, Roy Munson. Munson is a former bowling star who’s gone to seed, a self-pitying drunk with a prosthetic hand and a pathetic comb-over who latches on to an Amish naïf, Ishmael (Quaid), as his meal ticket. We’re meant to laugh at what a loser Munson is—his very name has become shorthand for blowing it—as a way of pardoning him for exploiting Ishmael for money and vicarious glory.

Still, Munson is more than just a sleazy, Jim Beam–swilling caricature. Harrelson plays him with genuine sympathy, grounding the character in a quiet sadness that balances out the film’s more cartoonish moments. Harrelson inhabits Munson so completely that it’s amazing to learn that the role wasn’t his at first, either. It was originally meant for Michael Keaton, who dropped out after deciding the script was too jokey. The Farrellys knew right away whom to call: their old friend Harrelson, who’d been Peter’s roommate in the early Cheers days. Harrelson had politely declined Jeff Daniels’s role in Dumb and Dumber, but in light of that film’s considerable success, he was more receptive this time. As the Farrellys recalled, they laid it all on a friendly game of pool, with Peter sinking the lucky shot that sealed the deal.

It’s hard to imagine Michael Keaton (or any other actor) taking on a scene like the one in which Roy Munson returns to his hometown and reckons with his squandered youth without making it feel stagy—rather than naturalistic and vulnerable, as Harrelson does. Buried under a prosthetic beer belly and yards of cheap polyester, Harrelson tapped into an ugliness he’d never even hinted at in previous roles, yet retained his soft center of humanity. It’s Harrelson’s aura of lost boyishness, eroded by so many years of cruel circumstance, that imbues Munson—and Kingpin—with true pathos.

Harrelson would go darker still in that fall’s The People vs. Larry Flynt, Milos Forman’s biopic about the founder of Hustler. You could say that Harrelson was being typecast again. Flynt was a Kentucky moonshiner’s son turned scuzzy strip club owner turned self-important pornographer. Harrelson found a spiritual kinship with this self-proclaimed “scumbag,” telling interviewers, “We’re both poor white trash hedonists who made good in the world—or made bad in the world.” Still, the film saw him honest-to-God acting, in a story that demanded far more from Harrelson than just his usual devilish twinkle. After Flynt is paralyzed in an assassination attempt, his early roguishness gives way to impotent rage, and his rancorous legal battles, leading to a landmark Supreme Court decision reinforcing free speech protections, find Harrelson pitching his gravelly voice to a Jimmy Stewart-esque tremble as Flynt defends his God-given right to be a pervert. It’s a brave and—again—fearlessly grotesque portrayal of a complicated man. Harrelson turned Flynt into someone you rooted for, felt sorry for, and found yourself repulsed by, often in the same scene.

In a CNN interview at the time, Harrelson seemed to think he was on a downward trajectory. He talked up his younger brother Brett Harrelson’s portrayal of Flynt’s younger brother, while downplaying his own movie career as “a bit lackluster,” in CNN’s paraphrase. But all that would quickly change. Although Harrelson was slightly overshadowed by Courtney Love’s surprise bravura turn as Althea, Flynt’s doomed, drug-addicted wife, Larry Flynt earned Harrelson his first-ever Oscar nomination. Critics such as Entertainment Weekly’s Owen Gleiberman hailed his performance as “brilliant [and] audacious.” Suddenly, Woody Harrelson wasn’t some country-fried himbo, barely skimming the surface of a role. He could take on the full, tragic span of a man’s life.

Do Kingpin or Larry Flynt rate as Harrelson’s best movies? Not really. (He’s done better comedy in Zombieland and tapped into darker, more dramatic places in The Messenger and Rampart.) But they’re arguably his most pivotal. Starring in a big, broad studio comedy and an Oscar-nominated biopic within the same year raised his profile considerably, proving his mettle as an actor, right when he needed it most.

Of course, he didn’t get to enjoy it for long. The feminist Gloria Steinem led a protest against The People vs. Larry Flynt—the third public squall Harrelson had endured in just two years and a campaign that Harrelson would later say “broke my heart.” Burned and burned-out, he spent the late nineties and early aughts in what he called “semiretirement,” focusing on his environmental activism and his family and making headlines for stunts like scaling the Golden Gate Bridge. Harrelson still acted, at times onstage, although he characterized the film parts he took during those years as “favors” for directors he admired. In 1999 Harrelson reteamed with White Men Can’t Jump writer-director Ron Shelton on Play It to the Bone, a boxing dramedy whose failure seems to have marked some sort of breaking point. Harrelson wasn’t seen on a movie screen again until 2003, at which point he began the process of proving himself all over again.

But thanks in large part to those two films released 25 years ago, Harrelson’s comeback always seemed like a matter of when, not if. Never again would anybody blink at Woody from Cheers taking on anything. Now his affability carries an undercurrent of depth; Harrelson’s characters in The Messenger (2009), Zombieland (2009), and The Hunger Games (2012) couldn’t be more different, but they’re linked by the way his natural, genial charms mask an inner pain. And he possesses an effortless center of gravity that steadies even the most outlandish spectacle, whether it’s the Star Wars aliens of Solo or a scenery-chewing McConaughey in True Detective. Our idea of Woody now encompasses everything from CIA agents to super-villains, from prestige drama to screwball comedy; his versatility is as unpredictable as it is reassuringly familiar. As Harrelson first showed us back in 1996, there are a lot of him in there.

This article appeared in the October 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Burying Woody Boyd.” A shorter version was originally published online on June 24, 2021. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Woody Harrelson

- Midland