The contributions of African Americans to our country’s barbecue culture are often overlooked. The influences can be hard to trace, which make it tempting to ignore them. Throughout Texas and the rest of the country, records of black barbecue culture are either gone or never existed in the first place. Most newspapers and magazines were written by and for whites, and mentions of black men and women making real social contributions were few, especially when it comes to restaurants. It takes some digging to piece together most of those stories.

But one history that has been especially well preserved is of Eugene “Hot Sauce” Williams. Williams wasn’t from Texas and never owned a Texas barbecue joint, and even though countless black Texans have made barbecue contributions just as impactful, no journalists at the time seemed to care enough to note them. We may never know about them, but thanks to the Call & Post newspaper in Cleveland, we can at least get a full picture of “Hot Sauce” Williams.

The Call & Post is a black newspaper that has been serving Cleveland since 1928. Between 1938 and Williams’s death in 1958, they wrote twenty-eight articles on the man and his beloved barbecue business (most of this story is drawn from those articles). That might not like seem like much in today’s food-obsessed journalism (guilty), but that’s 28 more mentions than I could find in the archives of the major (white) daily, the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Willams first came to Cleveland in 1923 after making his way from his native New Orleans through Memphis and Chicago. He found work as a cooper, but dreamed of owning a farm. His first attempt at the food business, a fish market, was short lived due to the Depression. Another local restaurateur was also hurting from the down economy, and in 1934 Sam “The Black King” Gleason (or possibly Henry Burkett, depending on the source) sold off his chain of Cleveland barbecue joints so he could move to Chicago. Williams paid $175 for the rights to a single location on East 40th and Central, and suddenly he was in the barbecue business

Williams was no rookie. His paternal grandfather, James Williams owned a “barbecue kiln” on Rampart Street in New Orleans, where Eugene apprenticed during the Depression. A 1950 Ebony profile says the younger Williams “spent days just drifting among cooks, gathering bits of information here and there on barbecue.” Back in Cleveland, Williams had spices shipped from New Orleans to create his own unique barbecue spice powder and sauce.

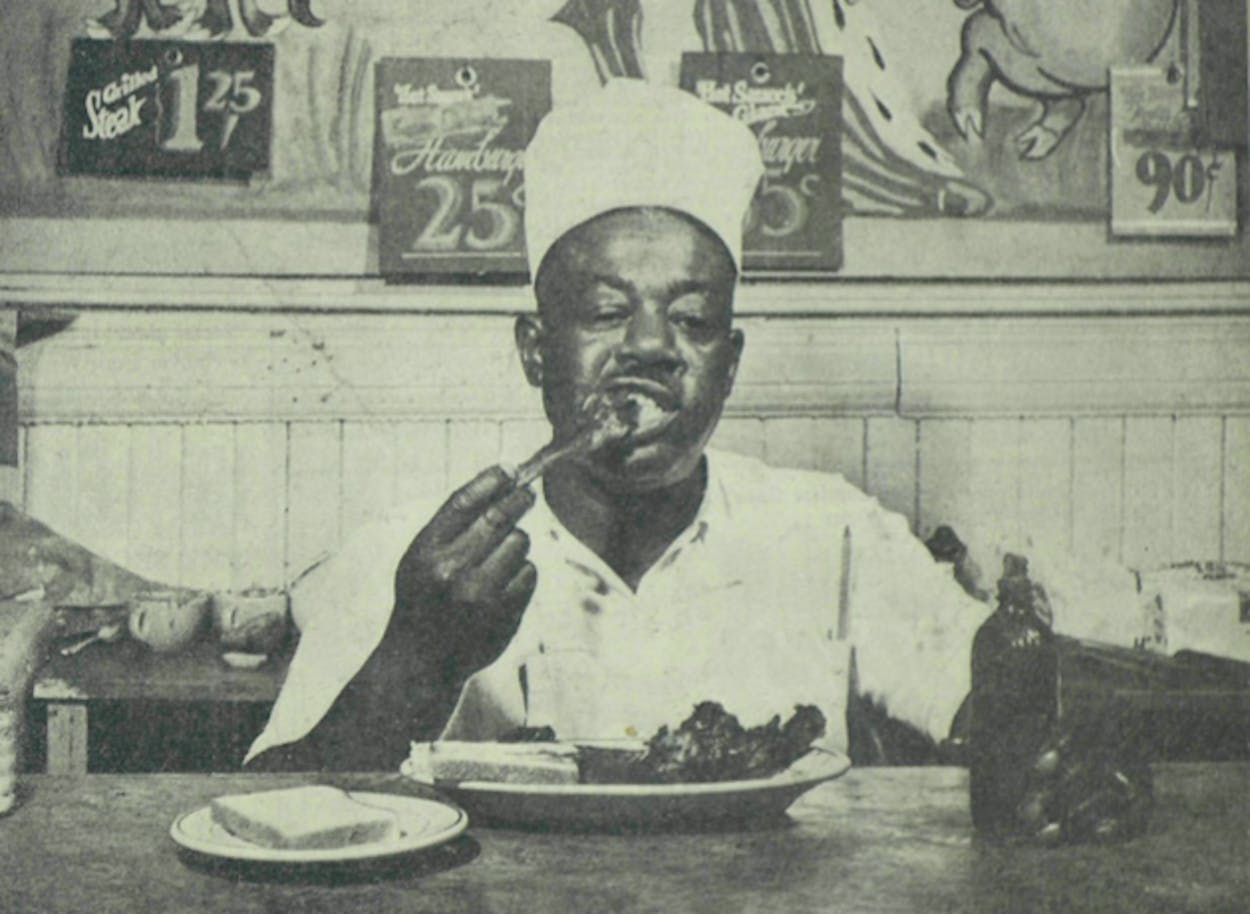

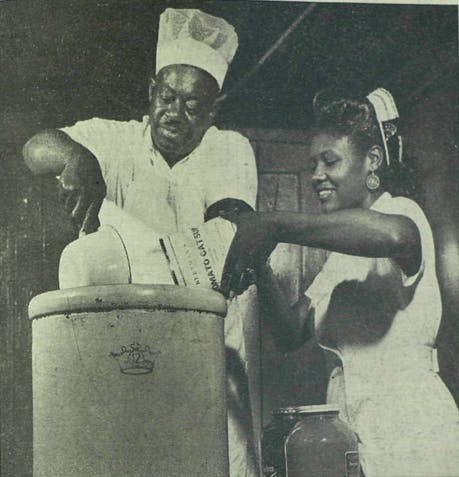

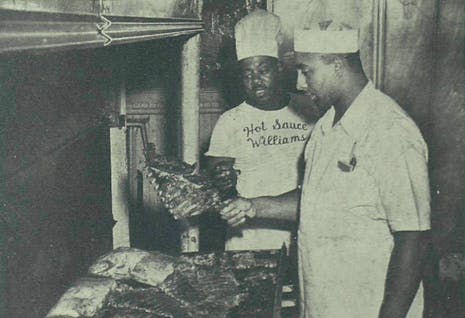

Judging by the 4,000 pounds of ribs he cooked over charcoal each week, the barbecue was a hit. Ebony said his success was “credited to the unique manner in which he flavors ribs with a dry spice powder and taste-tantalizing hot sauce.” Williams sprinkled the secret spices onto raw ribs before they were cooked. Today we would call that a rub, but the technique wasn’t common at the time. The sauce recipe, which he also learned in New Orleans and continued to perfect on his yearly trips to Mardi Gras, was just as much of a secret. He was the only one allowed to make it in the restaurants, and it was spicy. His nickname was “Hot Sauce,” after all, and his selling point was the “can’t-be-copied flavor.” Ever a pitmaster, though, he reminded Ebony: “Good cooking comes from proper timing and the right amount of heat.”

Five years into business, the Call & Post was already referring to him as the “King of Barbecue” in Cleveland. The name of the business changed from the humble Williams Bar-B-Que Stand to Williams World’s Best Bar-B-Q. Several locations were added in the 1940s, including one in Detroit. Williams sponsored a women’s bowling team, a women’s skating team, and boxer Jimmy (Beau) Brown. The menu expanded to include lamb and pig’s feet to weather the meat shortages during the war, but as the Call & Post put it, his name had “become a by-word for his world famous barbecue spare ribs and pork shoulder.”

Williams was also known for his shiny Cadillac that he drove every day to and from his farm, which was twenty miles east of town in Solon, Ohio. With 63 acres and a grand home, he’d finally realized his dream. In the 1950 Ebony profile (which I was first pointed to from the excellent book Hog & Hominy), they noted that Williams “plans to one day raise enough porkers to supply his barbecue needs.” That never happened, but the farm earned him another nickname: the Country Gentleman. With all that land, he no longer had to import his secret spices, and instead grew them himself. (None of the articles identify the herb, but I’ve got to wonder if it was filé powder.) According to Ebony, he was doing quite well for himself by 1950:

One of the most successful of all Negro barbecue operators in the U. S. today is the portly, 48-year-old ex-fish peddler, Eugene ‘Hot Sauce’ Williams, who has grossed more than $500,000 in the 16 years he has been selling ribs in Cleveland.

Williams counted Louis Armstrong as a childhood friend, and one that remained a big fan of his ribs. During one trip to Cleveland, Armstrong ordered 300 boxes of ribs. Williams served both black and white people, and counted “celebrities and civic leaders” among his clientele. The accolades kept coming with headlines from the Call & Post like “King of Barbecue Men!” and a proclamation in 1954 that, “Now, after 20 years of business here, Williams stands unchallenged as the monarch of the barbecue kingdom.” It was that year when Williams suffered his first stroke.

Even with his health deteriorating, Williams continued to work, but his finances had been drained through healthcare costs, bad business deals, and tax trouble. The farm was gone. He sold his beloved Cadillac and his home, and in 1956 he couldn’t pay the rent on the only “Hot Sauce” Williams restaurant* location left at Central and 55th. The Barbecue King had been locked out.

In the fall of 1958, a reporter from the Call & Post found him “ailing and lonely, loveless and nearly broke in the Highland View County Hospital.” He had suffered a series of strokes, and died of a heart attack two months later without any heirs and no money to pass down anyway.

With all the talk of the new barbecue joints in Cleveland, and of the creation of Cleveland-style barbecue, rarely is Eugene “Hot Sauce” Williams credited for already having creating one. Even Williams was humble enough to tell interviewees that “The Black King” had been responsible for making “Cleveland famous for good barbecue” before “Hot Sauce” took the crown. Although he was the “King of Barbecue,” his name isn’t even mentioned in the genesis story for the other Hot Sauce Williams restaurant opened just six years after his death.

I’m just grateful his life was recorded well enough that we can tell his story now. So often my research is relegated to the census records or city directories, and government records can only shed so much light. That’s why so many African American pitmasters will be forever buried in obscurity, but believe me that there are many more stories. We just need to keep digging.

*Eugene “Hot Sauce” Williams and his business are not to be confused with the Hot Sauce Williams restaurants that still operate in Cleveland, or their deceased founder Lemaud “Hot Sauce” Williams.

- More About:

- Black BBQ