The arrival of the National Football League in Dallas began with a party at my aunt and uncle’s Highland Park house. Friends, relatives, civic leaders, and the white-Stetson-wearing governor of Texas were all noshing on hors d’oeuvres and toasting with drinks held high early that Sunday morning before piling into buses parked along Beverly Drive with a bevy of police motorcycles ready to escort our entourage. As we began our nonstop, damn-the-red-lights journey to the stadium, my cousin Ed and I sat across the aisle from the governor, plying him with our youthful questions about whatever was important to us at the time—like who would prevail in a gridiron match-up between the Longhorns of the University of Texas and SMU’s Mustangs.

Expectations were high for the blue-and-silver clad team taking the field that day. The pro game was nowhere near the sports juggernaut it is today. Only twelve teams played in the league, and Dallas was the first in the South. Football lagged significantly behind baseball in polling of America’s favorite sports, and few games were televised. College matchups often drew far better than the pros—SMU and its Southwest Conference opponents regularly packed crowds into the Cotton Bowl’s capacity of 75,000. Yet surely, we thought, the NFL would draw interest from the sports-happy denizens of Big D, especially with the vaunted New York Giants in town for the inaugural contest.

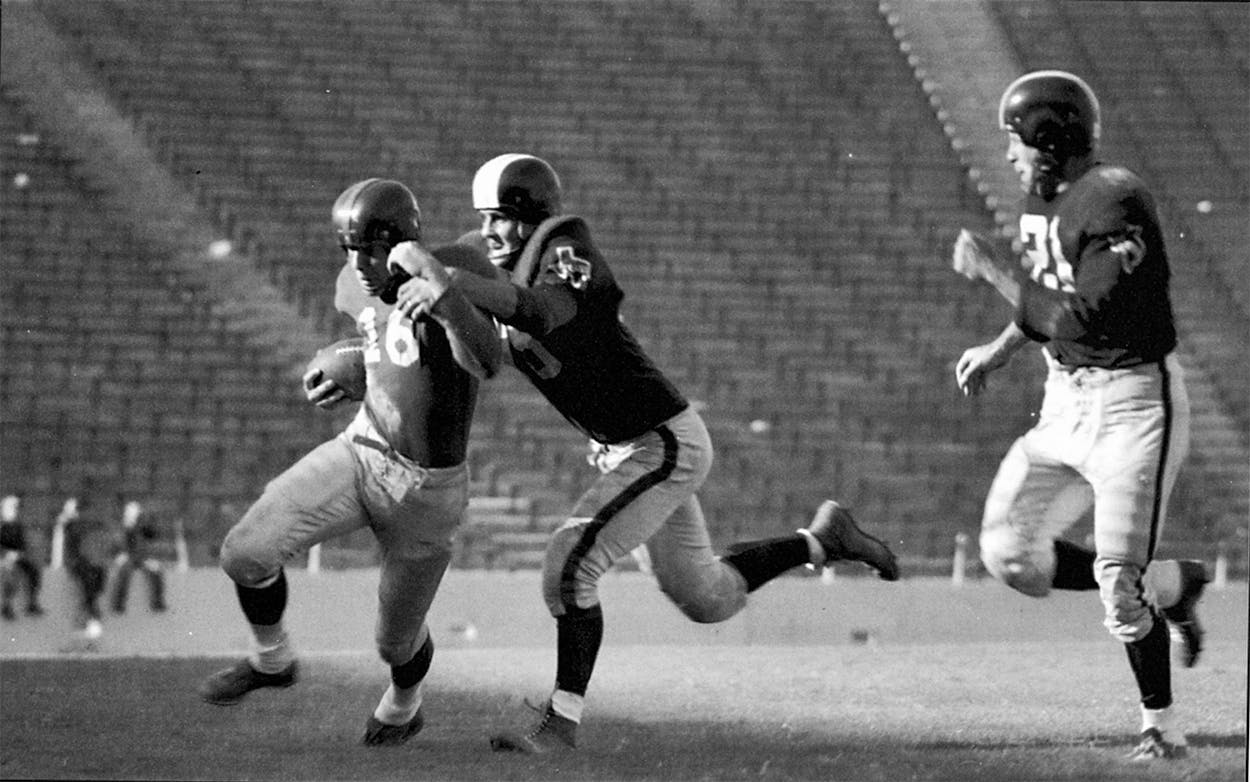

You’ll understand then why we were stunned as we settled into our seats, seeing just a tiny smattering of spectators. When our team rushed out onto the field that bright September morning, we heard only polite applause that quickly died as the refs convened the opening coin toss. It made for an inauspicious beginning and proved an unfortunately prescient omen of how that first season of pro football in Texas would go. Before the year was out, Dallas hadn’t just lost nearly all the games on its NFL schedule—the team itself was out of business.

My family, for better and for very much worse, stood at the center of it all.

You’ve probably guessed by now that I’m not talking about the Dallas Cowboys. Aside from some pigskin fanatics and sports historians, few people likely can name the team that first brought pro football to Texas, much less the convoluted path it took to get it here and the reasons for its exit after one not-so-glorious season. I’m intimately acquainted with that short-lived franchise because Giles and Connell Miller—my uncle and father—were owners of the original Dallas Texans, born in 1952, eight years before Lamar Hunt brought his Texans of the American Football League to town. Unfortunately, Dad and Uncle Giles also own the distinction of running the last NFL team to go bankrupt.

In those days you didn’t have to be a billionaire to buy an NFL club. The idea to do just that began with their friend Gordon McLendon, owner of Dallas radio station KLIF and founder of the Liberty Broadcasting System, a network of almost 500 affiliates that carried Major League Baseball games. For many of those broadcasts, McLendon sat in his studio in front of a Western Union stock ticker machine. Instead of spewing out corporate symbols and prices, the ticker tape gave him minute-by-minute reports of the action occurring at some far-off ballpark, which he used to communicate the play-by-play in real time, as if he were sitting in the press box. Indispensable in his ruse was his trusty sound-effects man, who provided pre-recorded crowd noise and the “crack” of the bat at the appropriate times.

But by 1951, many radio stations were launching local broadcasts and dropping out of the Liberty Network. McLendon was also embroiled in an antitrust suit against MLB over his right to air games in towns with their own minor-league teams. He thought that adding football broadcasts to his network could slow the exodus of stations and possibly recruit new affiliates. The decision was quickly made: he’d buy his own football team.

The New York Yanks were for sale. The team’s eight-year record of 23 wins out of 91 games indicated serious underachievement on the gridiron, but McLendon was undeterred. With no other major pro teams in Texas, this purchase (a bargain at $100,000) brought with it the potential to open up a new world for himself and his network. Unfortunately, when Bert Bell, the hard-nosed NFL commissioner, found out the particulars of Liberty’s suit against MLB, he rejected the broadcaster’s entry into the world of NFL ownership. So McClendon turned to two of his closest friends, persuading them to buy the team: Giles Miller, my then-31-year-old uncle, and his brother (my father) Connell, age 33.

Dad and Giles were rabid college football fans. On Saturdays, they, my mother Martha, and my aunt Betty Jane, joined the crowds at the Cotton Bowl to cheer on SMU, often with McLendon and his wife, Gay. Stadium tailgating hadn’t yet come of age, but the couples alternated hosting pre-game parties each week. For out-of-town games, they and their coterie of friends would travel by train, usually comprising a continuous party from the “All Aboard” to the “Please Watch Your Step.”

Giles was excited by the prospect of owning a team, and since they had worked closely for years running their father’s Texas Textile Mills—at one point the largest cotton milling operation west of the Mississippi River—he quickly convinced my dad to enter a 50/50 partnership with him. By then the asking price for the Yanks had ballooned to $300,000, since Commissioner Bell insisted the new ownership pay off the eight-year lease on Yankee Stadium, the team’s former home. Having seen the Cotton Bowl packed so many times over the years (averaging between 40,000 and 50,000 tickets sold for each home game), the brothers imagined the crowds a professional team might draw, and soon the contracts were signed.

A group of 12 investors was assembled, consisting of local businessmen and well-known oilmen like D. Harold Byrd (cousin of Arctic explorer Admiral Richard E. Byrd) and J. Curtis Sanford, who founded the annual Cotton Bowl Classic in 1937. George Leighton Dahl, the architect responsible for the beautiful Art Deco buildings in Dallas’ Fair Park, was also among the group. My aunt and mother, smart and business-savvy in their own right, became the first women to sit on the governing board of an NFL franchise.

When the details of the purchase were released to the press, the sports section of the Los Angeles Examiner posted a cartoon of a guitar-playing cowboy singing:

Oh, give me a home where the millionaires roam

And three hundred grand is just hay;

Where seldom is allowed a discouraging crowd

And the Cotton Bowl’s jammed every day!

I remember well the flurry of activity during long days and many nights, as Dad and Giles wrestled with details like opening a ticket sales office, securing Burnett Field (a Texas League baseball park in Oak Cliff) for the team’s practices, and negotiating a $60,000 fee for the Sunday use of the Cotton Bowl for the Texans’s six home games. Plans were hatched to offer the Detroit Lions $250,000 for Doak Walker, certain that the SMU standout and 1948 Heisman Trophy winner would spur ticket sales. However, the rumored buyout was of no interest to Detroit’s owners, who understood that much of their team’s success revolved around Walker. During this madness, Coach Jim Phelan and the players, along with a truckload of flyers, rolls of unused tickets, receipt books, Yanks letterhead, and worn-out equipment, came rolling down south to the team’s new headquarters.

After a preseason 27-7 loss to the Philadelphia Eagles at W.T. Barrett Stadium in Odessa, everyone’s nerves were on edge as the Giants arrived for the first regular-season game in the Cotton Bowl. The date was September 28, 1952. Our blue-and-silver jerseys (the same colors Clint Murchison would later choose for his Dallas Cowboys) were unused; the blue-with-a-white-stripe helmets were yet unscratched.

Not long after kickoff, the Texans scored first, after a fumble by a 27-year-old Giant running back named Tom Landry. (The first of countless football blessings Landry, later the Cowboys’s legendary coach, would ultimately bestow upon Dallas.) Unfortunately, the team never approached the Giants’ end zone again, losing 24-6. The Texans and those new uniforms were left much worse for wear at the hands of too many good players (another on that Giants team was future broadcaster Frank Gifford).

Giles, Dad, the sportswriters, and—most importantly—the investors, were most stunned that only 17,499 spectators had made their way through the turnstiles. Hopes had been that at least 50,000 tickets would sell. The Sporting News called the game “a flop by any standard.” To break even that first season, the Texans needed at least 25,000 fans at each home game—just half the number SMU typically drew.

The following week’s game came during the annual State Fair of Texas, and we thought many of its attendees would also watch the Texans battle the San Francisco 49ers. Fair Park itself was indeed packed that Sunday, but our guests, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, in town for some appearances, provided the day’s only levity for our group. An even smaller crowd of just 12,566 spectators saw quarterback Y.A. Tittle pick apart the Texans, 37–14. Next came losses to the Chicago Bears, Green Bay Packers, the 49ers (again), and two in a row to the Los Angeles Rams (the second of those at home, with a mere 10,000 paid admissions to the Cotton Bowl). During those first seven games, the Texans had been outscored 240 points to 101.

Even with little cash left in the bank, Dad and Giles believed they could raise enough money to salvage the season. They were turned away by banks they approached, so with thoughts of transforming the Texans into a quasi-public enterprise like the Green Bay Packers (a stock company), my uncle sought the help of the powerful Dallas Citizens Council in obtaining a $250,000 loan to carry the team through to the end of the season. Scared by the diminishing crowd sizes, the DCC didn’t come through with an offer. Then Commissioner Bell declined to offer any help from the league to keep the franchise going. “It’s time to call in the dogs, piss on the fire, and go home,” said investor D. Harold Byrd.

On November 12—little more than six weeks after the high spirits of that preseason party at my uncle’s house—the Dallas Texans were turned back over to the NFL due to “lack of funds.” With five scheduled games left, the now-orphaned franchise became a road team and were moved to Hershey, Pennsylvania. They finally won a game, a 27-23 squeaker over George Halas’ Chicago Bears on Thanksgiving at the Rubber Bowl in Akron, Ohio. For the 1953 season, Carroll Rosenbloom was granted a franchise for Baltimore, with most of the Texans players staying on to play for the Colts.

I have great memories of watching the Texans’s practices with Dad, getting to talk to the players and having one occasionally toss a pass my way or yell at me to throw one to him. While modern-day owners sit in glassed-in suites with padded chairs, stocked bars, and food served by white-jacketed waiters, nothing beat watching the action on the 50-yard line just up from the field, in those posterior-numbing folding metal chairs. I’m proud of what Dad and my uncle tried to accomplish. If only they’d waited until professional football had caught a greater share of the public’s attention, their Dallas Texans might have thrived.

My dad died in a car accident on Thanksgiving Day in 1954, so, in the ensuing years, it was left to my mother, Uncle Giles, and Aunt Betty (and sports historians) to reflect on the numerous reasons for the failure of the Texans. When income from advertising and TV and radio broadcast rights later added many millions of dollars annually to the coffers of NFL owners, the consensus became that the franchise had come around too soon.

A few years after the team’s demise, a reporter asked Giles what had prompted the two brothers to bring the first professional football team to Texas. My uncle sighed, shrugged his shoulders, and with a smile, simply replied: “Well, it seemed like the thing to do at the time.”

- More About:

- Sports

- NFL

- Football

- Tom Landry

- Dallas