“Matilda!” A man named Andrew Lockhart yelled above the chaos of an attack on a Comanche village. “If you are here, run to me!” From inside one of the lodges, fourteen-year-old Matilda Lockhart heard her father’s voice. She screamed back as loud as she could to let him know she was in the camp with the Indians who had captured her, but he couldn’t hear her above the noise of musket fire and the barking of dogs and the terrified shrieks of women and children.

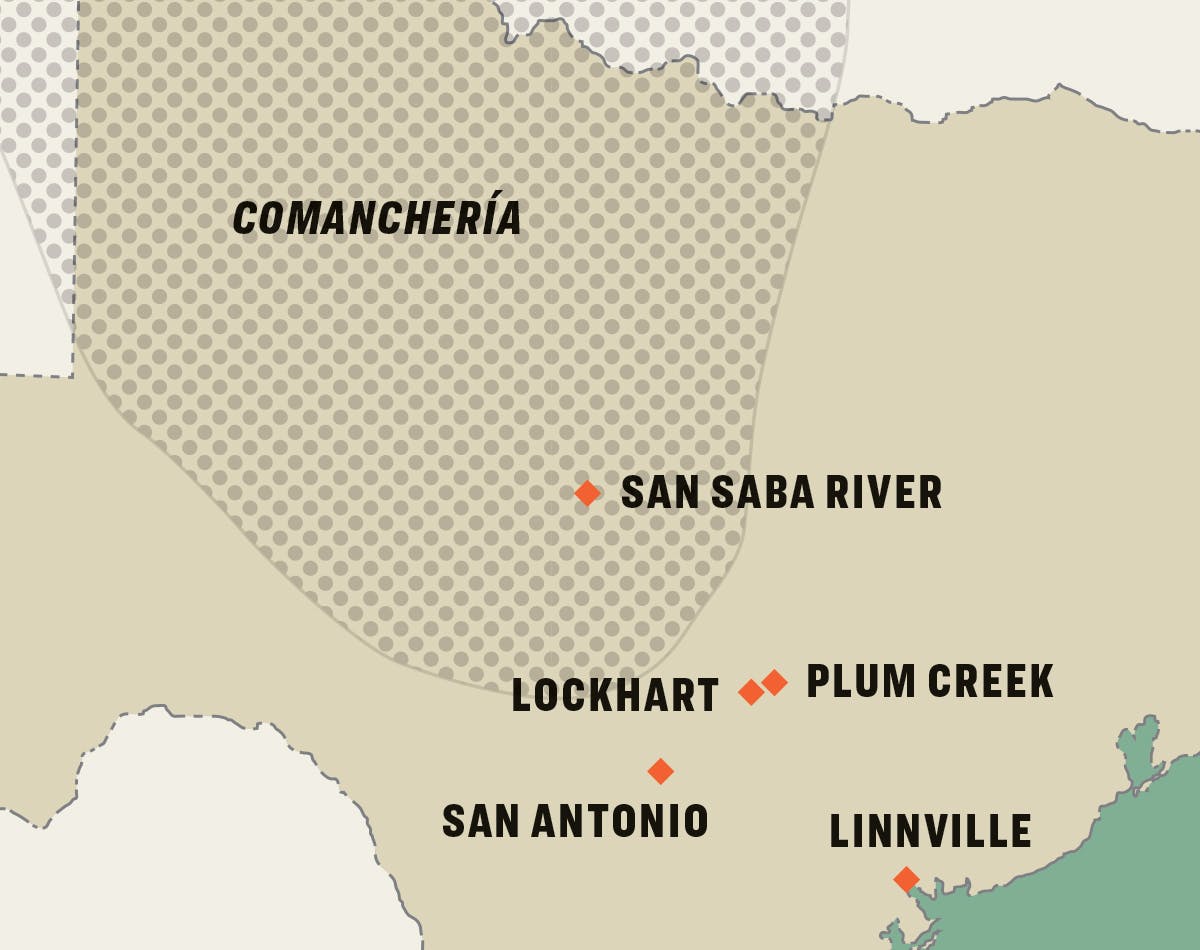

This happened in the winter of 1839 somewhere along the San Saba River. The attackers were a force of sixty Texas militiamen. They called themselves, informally, Rangers. The word had come into use among the early Anglo settlers in Texas to describe a mounted force necessary to help defend against Indian attacks. It was a concept that had long been field-tested by Tejanos and their fast-moving spying and pursuit outfits known as compañías volantes (“flying companies”). A “corps of Rangers” had been decreed into existence by the Texas provisional government in 1835, but it was not until 1866 that the state legislature would designate something officially known as a Texas Ranger.

With Lockhart and the other Rangers that day was a small force of Lipan Apaches under the leadership of a chief named Castro. The Lipans had discovered a Comanche encampment on the San Gabriel, forty or fifty miles north of Austin, and had enlisted the Texans to join them in a surprise assault on their common enemy. The Texans, especially Andrew Lockhart, were more than eager. Lockhart was a father of nine who had come to Texas in 1829. The previous fall, his daughter Matilda had been abducted along with four other white children while they were gathering pecans along the Guadalupe. The purpose of this raid was to retrieve the captives and bring the wrath of frontier vengeance down upon their abductors.

The Texans and Lipans found, when they reached the San Gabriel, that the Comanches had left, but they followed their trail through bitter winter weather until they located their camp on the San Saba, dismounted, and attacked in a wild rush, firing indiscriminately into the lodges. The Comanches fled, but the warriors regrouped and drove the Texans back into a cedar brake and then ran off their horses. “We were left afoot more than one hundred miles from home,” Noah Smithwick wrote in his recollections of this disastrous campaign.

Matilda Lockhart wasn’t rescued that day, but she was lucky she wasn’t killed along with the other women and children who must have perished in the attack. “I never felt sorrier for a man than I did for Colonel Lockhart,” Smithwick recalled of the forlorn father whose hopes of being reunited with his daughter had just evaporated.

But then, a year later, Matilda Lockhart suddenly appeared in San Antonio.

Twenty-two-year-old Mary Maverick was on hand to witness the terrible things that happened next. She was the wife of Sam Maverick, who had just finished his term as mayor of San Antonio, and the couple lived with their children and enslaved workers in a stone house off the main plaza. They had fenced off their garden and built a bathhouse at the edge of the river, beneath a magnificent cypress tree whose buckling roots made serpentine ridges through their yard. Sam kept a “war horse” in the padlocked stable, along with tack and firearms and provisions, so that at a moment’s notice he could saddle up and ride off with other members of his Ranger company in pursuit of Indians.

In January 1840, three Comanches of the Penateka band, whose home territory was the Southern Plains, rode into San Antonio to discuss peace. They were weary of constant border conflicts with the Texans and eager to establish a treaty to open up a more productive trading relationship. They were told that serious peace talks could begin only if they went back to Comanchería and, as a sign of good faith, returned with a number of Anglo captives believed to be held by the Comanches.

Two months later they returned. This time there were 65 of them, 30 warriors and 35 women and children. They came in high spirits, with goods to trade, apparently under the assumption that a formal peace would soon be concluded. But the Texans who received them were far more wary. Albert Sidney Johnston, the republic’s Secretary of War, had ordered three companies of troops to San Antonio and told the officer in charge that the Penateka chiefs were to be arrested if they didn’t produce all their other captives.

They brought only one. It was Matilda Lockhart. There is debate among historians over exactly what sort of condition she was in. Neither the official reports of what happened that day nor the scant surviving correspondence of the Lockhart family mention anything about Matilda’s appearance, but Mary Maverick’s memoir couldn’t have been more detailed:

They brought only one. It was Matilda Lockhart. There is debate among historians over exactly what sort of condition she was in. Neither the official reports of what happened that day nor the scant surviving correspondence of the Lockhart family mention anything about Matilda’s appearance, but Mary Maverick’s memoir couldn’t have been more detailed:

She was in a frightful condition, poor girl. . . . Her head, arms and face were full of bruises, and sores, and her nose actually burnt off to the bone—all the fleshy end gone, and a great scab formed on the end of the bone. Both nostrils were wide open and denuded of flesh. She told a piteous tale of how dreadfully the Indians had beaten her, and how they would wake her from sleep by sticking a chunk of fire to her flesh, especially to her nose. . . . Ah, it was sickening to behold, and made one’s blood boil for vengeance.

It may be that the Texans’ blood was indeed boiling, or it may be that Mary Maverick’s gruesome description—written toward the end of her life—was a latter-day justification for the slaughter that happened next. It took place in a dirt-floored meeting room called the Council House, which was attached to the jail. Twelve of the Comanche leaders were invited for a peace parley. Outside, the eighteen other Comanche warriors entertained themselves and the citizens of San Antonio with bow-and-arrow marksmanship displays while the chiefs and the Texas peace commissioners talked.

Inside the Council House, things quickly went wrong. The Texans demanded that the Indians bring in the rest of the hostages. The Penateka spokesman, a chief named Mukawarrah, said through an interpreter that Matilda Lockhart was the only hostage they had, but they would see what could be done—for a price—to ransom the other captives. A Texas colonel, William S. Fisher, conducted the negotiations. He was also in charge of the troops stationed against the walls of the Council House and guarding the exits. He told Mukawarrah that the other captives had to be returned. Until they were, the chiefs in this room would be held hostage.

Betrayed, enraged, realizing they were trapped, the Comanches reached for their weapons and moved for the doors. Within minutes, they were all dead, shot down in a close-range fusillade or stabbed or bludgeoned to death in the savage hand-to-hand fighting that followed. The Indians in the yard outside, who moments before had been peacefully demonstrating their skill with their bows and arrows, turned their weapons on the Texas troops or ran for safety through the streets of San Antonio. The fleeing warriors were hunted from house to house or shot down as they tried to cross the river. They all died. So did five Comanche women and children. The surviving women and children, plus two old men, were locked in the jail, next to the Council House, where their chiefs still lay on the blood-saturated dirt floor.

On the Texan side, seven were killed, including a judge and the sheriff. Ten others were wounded. A Russian doctor and naturalist named Weideman took part in the fight, chasing the fleeing Indians on his horse through the streets of the city. Late that afternoon, while Mary Maverick was visiting a neighbor, Dr. Weideman showed up with two Comanche heads, a male and a female. “I have been long exceedingly anxious to secure such specimens,” he told the ladies. He took the heads, as well as the bodies, and put them in a soap boiler so that he could render them down and study their skeletons. The boiler discharged into an acequia, which supplied the town’s drinking water. When horrified citizens saw what he had done, they had the doctor arrested. “He took it quite calmly,” Maverick reported. He assured everyone that the water was safe to drink and that the “Indian poison” had long since run off. He “paid his fine and went off laughing.”

There was lamentation in the Comanche villages when word arrived about what had happened in San Antonio. Their peace ministers had all been massacred, their wives and children—those that managed to survive—held as prisoners. The need for vengeance was unstoppable. Late in that summer of 1840, the Penatekas formed an invasion force with their Kiowa allies and rode down from the Hill Country onto the prairie, into the heart of Anglo Texas. There were about seven hundred of them, and they headed straight for the coast and descended upon a town called Linnville. Linnville was a small community on the shore of Lavaca Bay, only a few miles from where French colonists had once built a wilderness settlement. It was a perfect target for plunder, since it was a port with a customshouse where goods from the United States were unloaded before being distributed into the interior of Texas.

The several hundred people who lived in Linnville watched as a dust cloud two miles out on the horizon coalesced into a surging nightmarish storm front of screaming men wearing buffalo-horn headdresses and red and black war paint, waving lances and muskets, their horses churning up the prairie as they galloped toward the town. There was no possibility of stopping that sudden oncoming wave, so the citizens of Linnville jumped into boats and rowed themselves out into the bay or just took off swimming, where they were picked up by a ship that was coming into port to unload its cargo. Most of them survived, though the customs agent was killed and his wife captured. From their boats, they watched the marauders ransack and burn their town. The Comanches helped themselves to the goods sitting in the warehouses, trading their buffalo headdresses for top hats, covering their naked painted torsos with frock coats, twirling umbrellas as they rode out of town with the thousands of horses and mules they had liberated from Linnville and nearby Victoria.

It was a victorious caravan but a slow-moving one, far different from the usual lightning strike typical of Comanche warfare. The Indians were burdened with the livestock and warehouse goods they had captured and by the hundreds of women and children who were along on the expedition. Meanwhile, the alarm had spread quickly among the militias and Ranger units, and near the present-day town and barbecue mecca of Lockhart (named after Matilda’s uncle Byrd Lockhart) two hundred Texans intercepted the Indians’ sprawling line of march.

Read more: In this excerpt from ‘Big Wonderful Thing,’ set during the Civil War, German settlers actively resisted the Confederacy—and many of them paid the ultimate price.

Felix Huston, the former commander in chief of the Army of the Republic of Texas, was in command, but his tactics proved fruitlessly conventional. He ordered his men to dismount and form up to receive a charge. But the Comanches had no intention of riding straight into a wall of fire. They swarmed around Huston’s neat lines, flanking and encircling and harassing the enemy with separate charges while their women and noncombatants kept the huge herd of stolen horses moving behind them.

Within the Texan ranks were men who had more experience fighting Indians than Huston, and far less patience for antiquated military maneuvers. Among them were Texas Revolution notables like Edward Burleson and Rangers such as the soon-to-be-legendary Jack Hays, who had had hostile encounters with Comanches while working as a surveyor, and Mathew Caldwell, nicknamed “Old Paint” for the variegated color of his side-whiskers. Caldwell had been inside the San Antonio Council House when Mukawarrah and the other Comanche chiefs were killed. He had been shot in that fight, hit in the leg by a ricocheting ball, but even so he had dispatched two of the chiefs himself, shooting one in the head and beating the other to death with a musket.

James Wilson Nichols, whose memoir ranks among the most colorful and idiosyncratic in Texas literature, recorded Huston’s remarks to Burleson and Caldwell: “Gentlemen, those are the first wild Indians I ever saw and not being accustom to savage ware fare and both of you are, I think it would be doing you and your men especially great injustace for me to take the command.”

That was no problem for Caldwell and Burleson, who led a mounted charge that broke the Comanches’ momentum, scattered the warriors, and led to a running horseback fight that extended for fifteen miles. Although the conflict did not produce many casualties, it was a grisly demonstration of the kind of warfare that could be expected along the Texas frontier in the decades to come. Nichols described encountering an elderly Comanche woman in the midst of the fight. She was apparently guarding three prisoners—a black slave girl, a woman named Nancy Crosby (who, as it turned out, was the granddaughter of Daniel Boone), and a Mrs. Watts, who was the wife of the customs agent killed in Linnville. When she saw the Texans riding up on her, the old woman turned into a whirlwind of lethality, killing the slave girl with an arrow, shooting Mrs. Crosby with a gun, and firing another arrow into Mrs. Watts, who survived because (according to another witness) the arrow couldn’t penetrate her whalebone corset. Nichols killed the old Comanche woman before she could mount her horse and get away. He then joined the pursuit of the Indians on horseback, crossing a creek that was “litterly bridged with packs, dead and bogged down horses and mules.” He came across another Comanche woman, lying on the ground and shot through both thighs. A Texan father and son rode up. The father dismounted and handed his reins to his son.

He drew his long hack knife as he strode towards her, taken her by the long hair, pulled her head back and she gave him one imploring look and jabbered something in her own language and raised both hands as though she would consign her soul to the great sperit, and received the knife to her throat which cut from ear to ear, and she fell back and expired. He then plunged the knife to the hilt in her breast and twisted it round and round like he was grinding coffee, then drew it from the reathing boddy and returned the dripping instrement to its scabard without saying a word.

The Texans framed the Battle of Plum Creek as a decisive victory, though most of the Indians got away with most of the horses they had stolen. But the fight blunted the hubris of the Penatekas and only hardened the attitude, preached by people like Felix Huston and the Texas Republic’s bellicose president Mirabeau Lamar, that when it came to Comanches and the survival of the Texas nation, there could be no such thing as coexistence, only extermination.

Emboldened by having routed the Penateka expedition, the Texans took the fight into Comanchería. It was beyond the government’s nonexistent budget to field an army for this purpose, so it was left to the Rangers to head up the Brazos and Colorado and other river valleys in search of Indian villages to destroy. This they did systematically and indiscriminately—one Ranger colonel vaguely alluded to the dead inhabitants of a camp he had just attacked as belonging to “some northern tribe.”

The Rangers’ salaries, such as they were, were often raised by the communities they protected but were seriously supplemented by plunder—notably by the sale of the horse herds they took away from the smoldering Indian villages. But one has the sense they would have done the job for free. They were young men, by and large, who were drawn to extreme adventure, close comradeship, and dangerous purpose. Over time, they learned to fight like their enemy, traveling without baggage, without tents, without provisions except what they could kill along the way. “Most of them were dressed in skins,” recalled a Ranger from San Antonio many years later, “some wearing parts of buffalo robes, deer skins and bear skins, and some entirely naked to the waist, but having leggings and necessary breechclouts.”

One thing soon set them apart from the Comanches they hunted: a revolving five-shot pistol invented by Samuel Colt. The Paterson Colt fired a .36-caliber ball—undersized in comparison with the whopping .44-caliber pistol that would replace it—but the fact that it could discharge five shots in quick succession provided a serious tactical advantage for men who went into war while charging on horseback.

The first real test of the weapon—in 1844—occurred along a nameless creek in Central Texas. Jack Hays, the courteous, mild-seeming former surveyor who was fast becoming the most lethal Ranger leader, was in command of 15 men who engaged a party of around 75 Comanches. “Crowd them!” Hays called to his men during the close-order horseback fight. “Powder-burn them!” When the defeated Indians left the field, one Ranger was dead and three were wounded, but more than 40 Comanches had been blasted off their horses by the Paterson Colts. The pistols, Hays wrote in his official report, “did good execution,” adding, “I cannot recommend these arms too highly.”

Stephen Harrigan will be a featured speaker at EDGE: The Texas Monthly Festival in Dallas November 8-10. For tickets, visit edge.texasmonthly.com.

This article originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The New Texas History.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Stephen Harrigan