This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

As the cocktail hour passes in a modest Arlington living room, all eyes are fixed on an old Sears color television. On the screen, beneath the whir of a VCR, a familiar shadow stalks across the jungle. The chiseled jaw, the bullwhip, the fedora: It’s Indiana Jones. But the real entertainment comes from an orange flowered sofa near the set, where 62-year-old Vendyl Jones kicks back a tumbler of cognac and critiques the movie as if, in some wild Walter Mitty fantasy, he were watching himself in action.

There’s Indy up to his knees in slithering snakes. “We had that,” Jones drawls. There’s Indy walloping wicked Nazis, sneaky Arabs, and rival archaeologists. “We had that,” he says. There’s Indy clambering into caves, hanging on to ascending airplanes, outrunning a gigantic rolling boulder. “Oh, hell, that’s miniature compared to what we had,” he says. “Ours didn’t come rolling down a tube. Ours was more like a shotgun effect, with five-hundred-pound boulders flying everywhere, with tons of dirt and dust.”

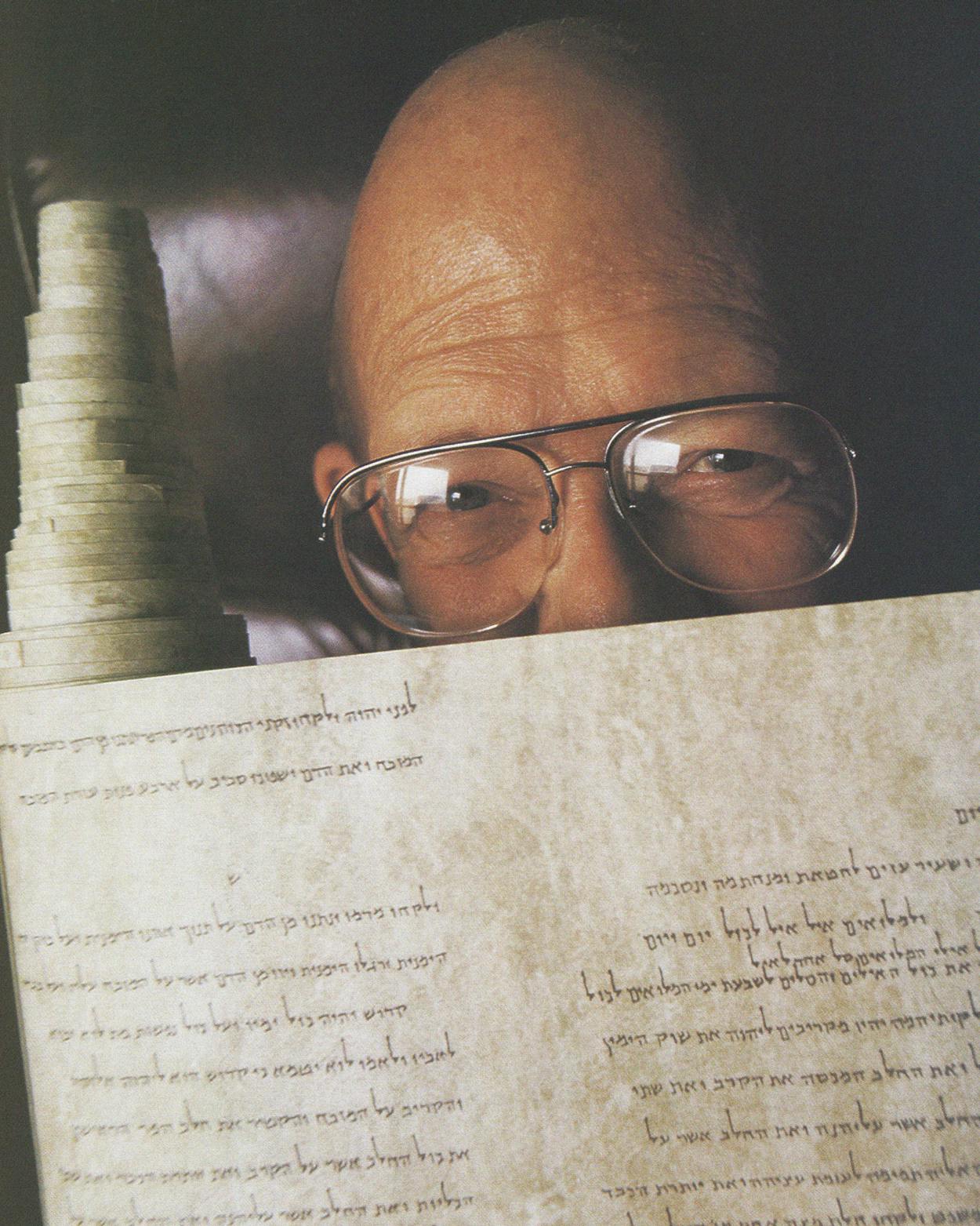

As if to prove his point, Jones pulls out a business card embossed with his name, then marks through the first and last letters of his first name, so that the card reads, “endy Jones.” “I may not be as young or as handsome as Harrison Ford,” he grins, running a callused palm over his shiny bald head, “but I sure part my hair straighter.”

Although it has been eleven years since the premiere of the first Indiana Jones movie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, a television prequel to the saga, The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, is about to begin its second season on ABC’s prime-time schedule. So the issue of Indy’s origins is hot on the minds of his fans—or at least on the mind of Vendyl Jones. Had it not been for his own exploits, Jones maintains, Indiana might never have been born. It is a not a claim he whispers shyly. As he travels the world, Vendyl Jones tells how George Lucas and Steven Spielberg’s swashbuckling hero was inspired not by some chiseled archaeological legend but by a jug-eared, potbellied amateur. Judging by the number of newspaper stories written about him lately, the message is getting through. When he makes one of his many appearances on radio or TV, Jones’s interviewers frequently salute him with the thundering Raiders theme song and introduce him as “the real Indiana Jones.”

Never mind that Lucas and Spielberg say they’ve never heard of Vendyl Jones. The way Hollywood really got the idea for the first Raiders movie, Vendyl says, is a tale befitting yet another Indy sequel—an action-adventure story whose cast includes a phantom writer, a thieving literary agent, crooked competitors, and much, much more. At the center of the action is, of course, Vendyl Jones himself, leading the sort of real-life treasure hunt that filmmakers only dream of. “The basic difference is that’s fiction, and we’re dealing with facts,” he insists, as he watches his namesake careen across the screen. “And if you compare our digs with the movie, the movie is a drag.”

This fall Vendyl Jones is plotting his ninth Israeli excavation, an experience that will make the adventures of that other guy seem like the antics of a California wimp. He swears he’s close to unearthing priceless biblical artifacts, maybe even the lost Ark of the Covenant. So from North Texas to the Middle East, the question persists: Is this the real Indiana—or just another Jones?

Long before Harrison Ford ever cracked a bullwhip, Vendyl Jones was in the ancient caves of Israel, following a treasure map taken from the Dead Sea Scrolls and searching for the kalal, the bronze vessel containing the sacrificial ashes of the red heifer. Described in Numbers 19:2, the ashes were vital for cleansing all those who stood before God in the ancient temple of Moses. Hidden by Jewish priests before the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70, they are believed to be buried with other temple treasures—chief among them the Ark of the Covenant, the chest bearing the stone tablets that God gave Moses and whose power can be restored only after being purified by the ashes. With the excavation of these treasures, it is said, the prophecy of the Bible will be fulfilled. God will return to the earth in a tongue of fire. The tented temple will be restored in a blaze of transcendent glory. Jews from all nations will return to Israel. And peace will come to the Middle East.

Over eleven years and five excavations, Vendyl Jones dug in the hellishly hot desert, defying the skepticism of those he calls “the swivel-chair academicians.” Dig after dig, as he came up without the temple treasures, the critics cackled. But in 1988, on his sixth outing, Jones and his team of volunteers unearthed a two-thousand-year-old juglet of oil mentioned in the copper scroll of the first century—oil believed to have anointed the ancient priests, kings, and prophets of Israel. The find made the front page of the New York Times and was lauded by National Geographic, Omni, and CNN. More important than the publicity, though, it gave Jones credibility. “He knows more about that area than anyone I know,” says Robert Eisenman, the chairman of the religious studies department at California State University, Long Beach. Sholomo Goren, Israel’s former chief rabbi, has praised Jones for “working for the good of Jewish people around the world.”

A Baptist preacher and Talmudic scholar, Jones is the president of the nonprofit Vendyl Jones Ministries, a.k.a. the Institute of Judaic-Christian Research, which from its Arlington industrial-district offices runs his desert excavations, publishes a monthly newsletter, and operates an audio- and videotape enterprise in its mission “to correct misinformation against Judaism, the Jewish people, and the State of Israel.” Jones also leads teachings in B’nai Noach (Judaism for non-Jews), holding local weekly Torah readings and helping to establish B’nai Noach groups around the country. With the aid of a part-time secretary and a two-man staff, and with only four hours of sleep a night, Jones functions as chief lecturer, promoter, fundraiser, archaeologist, author, adviser, oracle, holy man, and handyman.

The real Indiana? Well, there are similarities. Both Vendyl and Indy are bright yet sometimes bumbling characters, living precariously close to the edge. But while Indy is the strong, silent type, Vendyl could talk a zillion vipers into submission. His recounting of his own life sounds like the ultimate action-adventure story. It begins with endless tales of youthful fistfights in the West Texas town of Sudan, where he grew up the son of a barber and a beautician. “I went through all these years of rebellion, even got to the place where I tried to be an atheist,” he says one day, decked out in a gimme cap and a red Conoco windbreaker.

That rebelliousness never waned; soon he began fighting conventional theology. After graduating from a Baptist seminary with a master’s degree and serving as a Baptist minister in east Tennessee, Jones says he was awakened to the “greatest hoax of mankind”—the conspiracy of Christianity over Judaism. His belief that the New Testament was a fraud eventually led him to archaeology. “I’d always come back to the same thing: What about the Jew? The pitiful Jew. The wandering Jew. The paradox of the Jews surviving all the attempts to annihilate them,” he says. “It started with the Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325, when Constantine declared Christianity to be the official religion of the Roman Empire, and Christianity became a political force. The entire concept of Christianity was designed against Judaism and against the Jews. From 325 to 638, the Byzantine monks issued what they called holy edicts and sacred bulls, by which they changed the Sabbath from Saturday to Sunday. They changed Passover to Easter. They adopted the idea of the Jewish feast, but then they changed it and paganized it. The New Testament didn’t exist until the latter part of the fourth century, when the monks and church fathers got twenty-seven books together and called ’em the New Testament.

“I realized that the New Testament was, as a whole, a concoction of books and letters that were put together,” he says. “I learned the New Testament was not a ‘new testament.’ It was a collection of writings from the apostolic period that were put together in one book to replace the Old Testament. That was the idea of it. And Christianity replaced Judaism. The Christian replaced the Jew as the Chosen People, the church replaced the synagogue, Sunday replaced the Sabbath, and finally, Jesus replaced God. I felt it was wrong. I mean, what authority did these people have to come along and change anything?”

Biblical scholars like Bruce Metzger, the author of The Canon of the New Testament, are aghast at Jones’s interpretation of biblical history. “Any biblical scholar, even any Jewish scholar, would say that’s a bunch of hogwash,” Metzger says. But Jones was called to arms by his discoveries. “I felt a destiny in my life, a purpose,” he says, “although I didn’t know what it was.” In the mid-fifties he resigned his Tennessee pastorate and spent eight years focusing on Judaism and the Talmudic Torah. “A lot of the peers I had gone to school with, and pastors in the area, thought I had gone off my rocker, hobnobbing with the Jews and studying with a rabbi.”

Jones’s next move confirmed their suspicions. Eager to test his dogma on a congregation, he became the pastor of the First Baptist Church in Lynn, North Carolina, whose members were too busy feuding among themselves to realize they were being taught not the New Testament but the Torah. Jones’s tenure, from 1959 to 1964, almost cost him his life, he says. Incensed that he was allowing blacks to attend his services, Ku Klux Klansmen shot up his house and put nitroglycerine in his heating oil. Today Jones details his valiant fight for half an hour—fending off Klansmen! shotgunning car windows!—but in April 1967, he quietly packed up his first wife and five kids and moved to Israel.

He was intrigued by the history of the Dead Sea Scrolls—how they were discovered in 1947 when an illiterate bedouin goatherd threw a stone into a cave near the Dead Sea and heard it crash against a clay pot. As the story goes, after hanging the parchment and papyrus scrolls on tent poles for several weeks, the bedouin sold what they believed were rolls of old leather, perfect for sandal straps, to a Jerusalem cobbler. The scrolls finally found their way to Israeli historians, Jones says, on a prophetic day: November 29, 1947, the very date the United Nations partitioned Palestine, a move that led to the creation of the state of Israel. Spurred on by that find, Israeli archaeologists poked around the caves and uncovered a scroll hammered onto a nine-foot sheet of copper—the now-famous “copper scroll.” It described a “river of the dome”—a cave marked by a dome-shaped stone formation above a river—and approximately sixty places where the treasures of the ancient temple were hidden in caves along the Dead Sea. “The rock that cracked the crock in 1947 is still ricocheting throughout academic caverns, breaking up a lot of crackpot hypotheses of our day,” Jones wrote in his newsletter. “An illiterate young shepherd boy . . . is the paramount example that God has chosen the foolish things of the age to confound the wise.”

Some scholars pronounced the copper scroll a hoax, asserting that the bedouin tribe around Qumran had stolen all the treasures between 1947 and 1953. Jordan’s King Hussein had the caves declared off-limits to Israeli excavation. Yet Vendyl Jones was convinced. In a honeycomb of four hundred caves about twelve miles east of Jerusalem, he believed, were treasures that would nullify the religions that replaced Judaism—and would vindicate his own embattled philosophies. “If I could find these things,” he says, “the supremacy of Judaism would be proven.”

Vendyl Jones drives a pickup truck as long as a limousine, a $32,000 Ford XLT Lariat customized with a sixteen-ton winch, fog lights, a camper with seating for a dozen diggers, and big blue “B’nai Noach” signs on the sides. “I had to wait six months to get this,” he drawls. “I bought it to take to Israel to ferry diggers from the kibbutz to the cave. But the customs, duty, and taxes came to thirty thousand.”

So the truck is landlocked in Arlington, where it is used to ferry Jones between his many speeches to religious groups, civic organizations, and would-be expedition volunteers. Today, headed toward downtown Dallas, he tells the story of his Israeli adventures. They began just after the Six Day War in 1967, in which Jones says he was the only non-Jewish American to fight for Israel. He was enrolled in the department of Judaica at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, but his real schooling occurred in the desert, where he wandered constantly, searching for the river of the dome described in the copper scroll.

One evening in April 1968, Jones recognized a gangly, gray-haired neighbor walking near the Jerusalem YMCA and gave him a lift. “Before we got to his house,” Jones says, “he asked me my name and I said, ‘Jones. Vendyl Jones.’ ” The man asked if he was Jones the Baptist, a reference to the “Texas Reverend Vendyl Jones” lauded in the Israeli press for his help during the Six Day War. “And he leaned over, kissed me on the cheek, and said, ‘God bless you! I would like you to come to my house for coffee!’ ” Jones recalls. “He said I’d have to forgive the condition of his home because his wife was deceased. So I said, ‘Why don’t you come to our house for supper?’ Then I realized I didn’t even know the man’s name.” As it happened, the man was Pesach Bar-Adon, a leading Israeli archaeologist and author. “I leaned over and kissed him on the cheek,” Jones says. “I told him, ‘Bring your maps! I want to discuss the desert!’ ”

That night, over a Southern-fried chicken supper, Jones told Bar-Adon of his quest: to find the Nahal HaKippa, the river of the dome. Bar-Adon smiled. Everyone wanted to find the river of the dome, Bar-Adon said, but he himself had searched for years and had found nothing.

That didn’t stop Jones, however. A few months later, on September 18, 1968, he stood jubilant in the desert, shouting, “Wahad bibi!” (Arabic for “My only sweetheart”). After commissioning aerial photographs, Jones was certain he had found the site described in the copper scroll—a small wadi, or dry riverbed, with a dome adjacent to a double cave divided by a column near an area called Qumran. On an ancient map, he discovered its ancient name: Secacah. Wild with excitement, he tried to reach Bar-Adon. When he couldn’t, he contacted two Israeli university professors, took them to the cave, and blurted out what he thought he had found.

Jones stares at the highway, still smarting from the memories. “I wanted them to excavate it, and I just wanted to be on the team!” he remembers. “But they said, ‘There’s problems, problems. We can’t excavate here.’ Then the next weekend they went down with a bunch of university students and didn’t even invite me to go! You know, I showed ’em the cave. I showed ’em the column. They’re sold. And then they get a bunch of students and didn’t even say, ‘Shalom.’ ”

The professors dug down to bedrock and found nothing. But Jones persisted. When he returned to the cave, he didn’t tell anybody, not even Pesach Bar-Adon. “Everything fit so perfectly according the scroll,” he says. “And there’s bedrock. What are you gonna do? Argue with the stone? So I sat in the cave looking at the bedrock, studying it. It was just horizontal bedrock. But as I looked up, the ceiling of the cave was vertical strike and very jagged. Now, if you’ve got vertical strike walls and a vertical strike ceiling, you should have a vertical strike floor. In other words, the bedrock should be uneven, right? But this was just as smooth as pavement. I said to myself, ‘Wait a minute! That might not be bedrock.’ ”

Jones and two Arab boys dug deep and discovered that his assumption was right—the “bedrock” was actually concrete. “I had been taught that concrete didn’t come along until the tenth or eleventh century,” he says. “But here you had concrete. So I went through the concrete floor and about three and a half feet below I hit a solid plaster floor. And in just a little shaft we picked up several pieces of Qumran pottery and twigs, branches of trees that had to have been there over two thousand years.”

But then Jones suddenly had to leave Israel. His son needed a kidney transplant, and he would be the donor. When he returned to Israel in 1977, he had three things going for him. A California couple who had heard him deliver a speech in Van Nuys anted up $5,000 to join him on his first full-scale excavation. Pesach Bar-Adon had scurried down into Jones’s cave after hearing about the concrete floor and happily emerged from the darkness with a deal: If Jones would supply the money and the manpower, Bar-Adon would furnish the expertise and permits. And Randy Filmore, an out-of-work freelance writer from Baltimore was ready to make Vendyl Jones famous.

Or at least that’s the way Jones tells it. The writer cannot be found to vouch for himself—although Jones has a picture of the tall, thin, bearded Filmore huddling with his 1977 dig crew, and members of the crew have confirmed Filmore’s existence. “He was a freelance writer who wrote TV scripts, trying to create a five-part series on the Israeli military, but the military wouldn’t cooperate,” Jones recalls. “He was living in a kibbutz. But kibbutz life was so dead that he found nothing to write about there. He didn’t have anything to do, so he volunteered for our dig. He wanted to do an article about the search for the temple treasures.”

Jones says he talked to Filmore with one stipulation. The writer had to promise not to reveal the location of the cave or the identities of the excavators. “I didn’t want a bunch of treasure hunters up there,” he says. But with typical verbosity, Jones regaled Filmore and the other volunteers with endless tales of the lost treasures. He told the story of the late German archaeologist A. F. Futterer, who wrote about his bitter competition with the British in his dogged search for the Ark of the Covenant in the twenties. He paraphrased Zechariah 14:12 about what will happen once the Ark is opened: “And the Lord will send a plague to all the people who fought Jerusalem. They will become like walking corpses, their flesh rotting away; their eyes will shrivel in their sockets; and their tongues will decay in their mouths.” He showed off his West Texas handiwork when, Jones swears, he whipped five Arab pickpockets at once on a Jerusalem street while Filmore watched nearby. Finally, he introduced Filmore to his son, Gershum Bar Yones (Hebrew for “son of Jones”), who wore a cowboy hat as his fedora and actually cracked a bullwhip.

“In April 1979, I got a call from Randy,” Jones says happily. “He was real excited. He had shown his story to an agent, who said, ‘I want to show this to some people in Hollywood. I think it could be made into a film.’ ” When Jones returned to Tyler, which was then his home, after his second dig in late 1980, the premiere of Raiders of the Lost Ark was approaching—and without a word about Vendyl Jones or Randy Filmore. “Once the movie came out, everybody from the dig was calling, saying, ‘Vendyl, you had to have had something to do with this movie. There are just too many similarities with things that happened on our dig.’ ”

When Jones finally made contact with Filmore five years later, the writer claimed that he had been bushwhacked. He’d given the only copy of his manuscript to the agent, but then never heard from him again. “I was his only witness,” Jones says. “And when he first saw a promotional article about the movie, he tried to call me. But I wasn’t in the country. He told me, ‘If I was going to sue, I needed to do it up front, and I tried to call you. But now it’s too long after the fact.’ ” After that meeting, Jones never saw or heard from Filmore again.

But even without mentioning Vendyl Jones, the movie had an oddly positive effect on him. It started with a news story on the front page of the October 11, 1981, Tyler Morning Telegraph, under the headline TYLERITE HUNTS ARK OF COVENANT. Illustrated with a photo of Vendyl shrugging before a poster of Indy at Tyler’s Cinema 4 Theater, the story detailed his quest: “Tyler has its own ‘Raider’ of the Lost Ark. His real name is Jones just like the ‘Indiana Jones’ in the box office smash movie Raiders of the Lost Ark. But he’s ‘Texas’ Jones.”

After that first article, the story of Vendyl Jones’s search for the lost treasures of Israel was carried by dozens of newspapers, religious radio stations, and TV talk shows. Interest in Jones’s excavations “exploded,” he says. A Dallas philanthropist even donated $50,000 to the cause. And although Jones had led his 1977 and 1979 excavations with fewer than twenty volunteers, his third excavation, in 1982, attracted two different shifts of sixty. Each volunteer paid $1,250 in airfare and expenses to spend two months in the desert excavating hundreds of pounds of dirt and rock at the side of “the real Indiana Jones.” Vendyl Jones had become a star.

“Okay, who’s seen the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark?” asks the president of the downtown Dallas Kiwanis Club, and his audience breaks into applause. “Well, it’s a true story. But Steven Spielberg was afraid he’d lose his credibility if he called it Texas Jones. But now, here he is, the real Indiana Jones, Professor Vendyl Jones!”

It is less than one month before the spring departure date for his eighth dig in the desert, and Vendyl Jones is making the Dallas media rounds. In his pin-striped suit and pointy-toed shoe boots, he has hit every stop from the Kiwanis Club to KLIF Talk Radio, until his country-boy baritone seems to be booming from every speaker in town.

“So, the movie was loosely based on you?” asks Al from Garland.

“Is the translation of the New Testament a farce?” asks Ed from North Dallas.

The speeches and the interviews always end the same way. “Can I make a commercial?” Jones asks on KLIF. “We have twenty-seven volunteers. We need fifty. So if anyone would like to go on our dig, just call Vendyl Jones. I’m listed in the Arlington phone book.”

Jones needs fifty volunteers for an optimum two-month excavation. And while a little more than half have confirmed, only seven have paid the $2,950 all-inclusive fee. Jones has amassed $250,000 worth of excavation equipment in the Judean desert and has assembled an impressive team of volunteer advisers: a Texas Department of Transportation supervisor, a Harvard Ph.D., and the senior archaeologist for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. But if he can’t come up with enough volunteers, there might not be any dig at all. “It’s all about getting the word out,” he says.

A few days later, Jones is back at his seemingly typical suburban home, whose mortgage, like his truck and his $8,000-a-year salary, is paid by his institute. Inside, however, the house is typical of Israel. Israeli art and photographs cover the walls. Israeli food is in the kitchen. And waiting for Jones is his young Israeli wife, Zahava, a linguist fluent in ancient Hebrew, who carries her own painstaking translation of the copper scroll in her purse.

How Vendyl and Zahava met is yet another tale in Jones’s endless inventory—a wily Israeli matchmaker! a plane scene straight out of Casablanca! “I needed a wife who loved God, Torah, and Israel,” he says. “And I knew I wasn’t gonna find that in a Baylor broad.” Zahava Jones crystallizes their courtship into a single meeting. She was working the reception desk at the Argaman Hotel in Acre, when she noticed the then-divorced Jones—“dressed like Indiana Jones: hat, khaki shirt, and pants and boots”—staring at her. “I asked him, ‘You want something?’ ” she remembers. “And he said, ‘Yes. I want to look at you.’ So a few days later, I said, ‘Are you married?’ He said, ‘No.’ I said, ‘Are you Jewish?’ And he said, ‘No. You want to check?’ ” Jones flashes a sheepish grin and pretends to unzip his pants. “Meshugah!” Zahava screams.

The next day, Jones is busy in his office. The deadline for booking cut-rate airline tickets is approaching; he is running short of both volunteers and patience. He has been up all night working on the arrangements for the excavation. He is overseeing a team of editors and proofreaders, trying to beat a printing deadline for the current issue of his newsletter. (The headline: EXCAVATION UPDATE . . . COST REDUCED!) He is also preparing to meet with representatives of NASA, whose high-tech satellite equipment he wants to enlist to search for underground cavities in his caves.

And if that’s not enough, his day has been darkened by news of that other Jones. He is shown a copy of the current TV Guide, its cover picturing young Indiana riding a camel alongside the line “Indy and Me, by George Lucas.” Jones reads Lucas’ story aloud: “The character’s name came from my dog Indiana, who used to sit in the room with me while I was writing. I originally called the character Indiana Smith, but Steven Spielberg said it sounded too much like Nevada Smith, a movie character played by Steve McQueen. I suggested Indiana Jones.”

Jones puts down the magazine. “Well, isn’t that interesting,” he says, then falls silent for a moment. “I don’t think he stole this. But I think he got Randy Filmore’s manuscript. I don’t buy that he just pulled this thing out of the sky.” But Lynne Hale of LucasFilm says the first Raiders screenplay was an original story written by George Lucas in 1973—which predates Jones’s meeting with Randy Filmore by four years—and was inspired by Lucas’ love of the high-action cliffhanger serials of his youth. “It was not based on Wen-dyl Jones at all,” Hale told me.

“It doesn’t matter,” says Jones. “First of all, I would never sue Spielberg and Lucas because of what they did to spread the knowledge of the Ark of the Covenant. For four thousand years we’ve had rabbis around, and nobody got this story across like Spielberg and Lucas. But the bottom line is this: If Randy Filmore had not been on that dig, if there was not an Indiana Jones, it would not affect me and what I’m doing. I was doing it for years before all of that came off. It added a little gee-whizzism. But gee-whizzism doesn’t move dirt in buckets. It doesn’t raise money for the dig.”

He is told of the skepticism of scholars like Jacob Neusner, the author of two books on the ashes of the red heifer, who says, “[Jones] would be better off to go to the stockyards of Fort Worth and take a red cow to Jerusalem on El Al and burn it on the Mount of Olives. It would have the same effect [as finding the ashes]. [His quest] is a wonderful, romantic idea and absolutely crackpot.”

“So what?” asks Jones. “How much time have they spent excavating in the caves of Qumran?” He is sick and tired of the academics who have never personally dug in the desert and the reporters who always sandwich stories of his search between quotes from skeptical scholars. “If they want to write an article about what we’re doing, fine,” he says. “But if they want to ask Dr. Smellfungus and Dr. Picklesheimer, and all these bastards out here who don’t know anything about anything, much less about what I’m doing in the desert, then that’s something else. They don’t know anything about Qumran! They don’t read Hebrew! If they wanna get the story from some reformed rabbi who went to Hebrew Union College and studied more Christian theology than Judaism, you know, let ’em go and get the story from them! Don’t take my story and pitch it out to people who don’t know what they’re talking about.”

He tosses the TV Guide onto his desk. “Eh,” he says. “I don’t care. I’m totally immune. You know what you have to do to get a dog to bark at you? Go somewhere, do something. Just get out and start walking down a street, especially at night.” He begins barking like a dog—“Woof, woof!”—howling louder and louder, then imitating various breeds and sizes. “One doesn’t even see what the other one is barking at. And the first thing you know, the whole neighborhood is barking because one little feist, who ain’t gonna do nothing, began to bark.”

Jones rises amid walls covered in books, maps, and photographs from the Holy Land. There’s a picture of him with the former chief rabbi of Israel. There’s Jones’s calendar, packed with speaking engagements for the fall. And always over his shoulder is a copy of a fifteenth-century woodcut depicting the long-horned red heifer, which is the same screaming burnt-orange color as the Indiana Jones nameplate on his desk. Jones translates the ancient Hebrew writing on the woodcut. “There is a Gentile who is not an idol worshiper, a Gentile who believes in one God, and he will find the ashes . . . And they will sweep every corner until they have found her.”

So where are the ashes of the red heifer? In the caves of Qumran, says Vendyl Jones. It was there that he made his pivotal find: the two thousand-year-old juglet of anointing oil. How he found it is yet another adventure. It began when his mentor, Pesach Bar-Adon, died of a stroke in 1984. Israeli archaeologists combed Bar-Adon’s office like a lost tomb, unearthing a collection of ancient pottery. Where had it come from? The Qumran caves being excavated by the Texan, Vendyl Jones, the archaeologists were told. Suddenly, interest in Qumran—an area everyone believed had been pillaged by the bedouins—was awakened. Rival treasure hunters joined the fray. First, Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin commissioned a study of the caves there, appointing Hebrew University–affiliated archaeologist Joseph Patrich to survey them. Then, Jones says, the director of Israel’s Institute of Archaeology, Avi Itan, instructed the archaeological officer over the Judean and Samarian deserts not to reissue a permit for Jones’s 1986 dig in Qumran.

“They were yo-yoing me between one office and another,” Jones says. “So I took Professor Ernest Easterly from LSU, one of the American archaeologists on our team, who has a Ph.D. in geography and a doctorate in international law as applied to archaeology. We went to Avi Itan’s office, and I told him, ‘Avi, come Sunday morning, I’m gonna have forty-three people on that hill, and we’re gonna start an excavation. You can either issue us a permit number or bring a court order to stop us. I would like to introduce you to our attorney, who has prepared a writ of mandamus to the Supreme Court of Israel.’ ”

Two weeks after his visit to Itan’s office, the permit was issued—with the stipulation that Jones turn over all of his maps and data. In the second month of the dig, Patrich arrived, spouting compliments. “He said no one in Israel had the know-how of cave excavations I had demonstrated in the Cave of the Column,” Jones recalls. “He said, ‘If anyone will find the treasures of the copper scroll, it will be Vendyl Jones.’ ”

Two days later, Jones says, Patrich returned with a proposal. “He said, ‘You have so many people, it would be wonderful if we could work together. If I could have ten or twelve of your volunteers, we could begin excavations in the four nearby caves where the temple scroll was found.’ So I agreed to make a consortium effort between the Institute of Judaic-Christian Research—my team—and Joseph Patrich and his two assistants and Hebrew University.”

So in 1986 and 1988, the two teams excavated simultaneously with two very different goals. Jones and his crew searched for the temple treasures in the Cave of the Column, while Patrich and his assistants and about a dozen of Jones’s volunteers searched for more conventional relics in four caves nearby. One day on the 1988 dig, while Patrich was away at the university, Jones’s volunteers hit a stretch of pale sand, then palm leaves, in Cave Twenty-Four, one of the caves Patrich had designated for excavation. Excited, they called for help. That’s when Patrich’s assistant pulled a small, basket-encrusted juglet from the ground. “When they took it out, they just thought it was probably full of dirt,” Jones says. “But when they got it in the sun, this ointment began to ooze out of it. I didn’t know it was the anointing oil. Nobody knew. Patrich came to me and wanted five thousand dollars to do an analysis on this stuff.”

Jones paid the money and left for Texas. When he returned to Israel in February 1989, on the eve of his seventh dig, he turned on the TV and saw Joseph Patrich, beaming over one of the greatest archaeological finds in modern Israel: the anointing oil, perhaps one of the bottles of oil mentioned in the copper scroll.

“I thought, What the hell is this?” Jones shouts. “It’s very strange that I paid for the report and I hadn’t heard about it! Very strange that I paid his salary, and the salary of his two assistants, spending more than $30,000 for two and a half years, while they worked on what was supposed to have been a consortium effort! But on TV, he is the one who found the oil. He even denied credit to his assistant. Patrich wasn’t even on the dig for ten days before we found the oil. I called him up and said, ‘Joseph, this is Vendyl!’ And he said, ‘Oh, I am glad you are here. I have good news for you!’ And I said, ‘I saw you on TV tonight, and I didn’t hear any mention of who financed the dig—only Joseph Patrich. My opinion is that when God created the world, he created one more horse’s ass than there are horses, and I’m talking to him now.’ ”

News of the find traveled around the world—at first with no mention of Vendyl Jones. However, the New York Times mentioned Jones and his volunteers on an inside page of the paper, after leading with Patrich on the front page, and the Jerusalem Post headlined a story TEXAN UNSUNG HERO OF QUMRAN. But when Patrich wrote an eleven-page account of the dig in the Biblical Archaeology Review—with no mention of Vendyl Jones—the Texan’s volunteers revolted, writing letters to the editor such as this one from an Athens, Tennessee, minister named J. David Davis: “Please give credit where credit is due. Let those who sweated, cried, and bled on these digs know that the record can be corrected.”

During his next Israeli dig, Vendyl Jones settled the score on his own. He fired Joseph Patrich. “He had the chutzpah to tell me that I used him to become famous,” Jones says, wincing.

Until recently, Patrich was on sabbatical at the Harvard-affiliated Dunbarton Oaks, a research center in Washington, D.C. While he commends Jones for his excellent organizational abilities and the money and manpower the Texan has brought to Israel, he says that Jones’s search for the ashes is a pipe dream and that his efforts would be better used to excavate other caves for more realistic relics. “He’s not interested in archaeology too much, only in his fundamentalistic ideas,” says Patrich with a laugh. “What does the anointing oil have to do with the temple artifacts? He’s just wasting money and wasting time and wasting the goodwill of the people because of the place he insists on excavating.”

So Patrich was not honored to work beside the real Indiana Jones? The laugh grows into a roar. “What does it have to do with this particular person, other than that he is a Jones?” he asks. “There are maybe a hundred thousand million other Joneses in America. Indiana Jones! What does it have to do with this person?”

Then Patrich stops laughing. “So what do you know about the excavation?” he asks, pumping for information about Jones’s upcoming dig. “When is he going again? When is the next season scheduled?”

On March 29, Jones and 35 volunteers took off for Israel in search of the ashes of the red heifer. By mid-April, they had unearthed nine hundred pounds of a red substance believed to be Second Temple incense. A month later, however, the Israeli Department of Antiquities canceled Jones’s permit and ordered him to shut the dig down.

But Jones would not be deterred: He refused to leave the site without a court order, challenged the Israeli bureaucracy in the press, and threatened to petition the courts for access to the caves. Now back in Arlington, he’s plotting another excavation, a seven-month dig that he’s confident will uncover the ashes. Even then, Jones’s quest will continue—until he’s found all the lost treasures. “There’s four hundred caves down there, and only forty have been excavated or plundered,” he says. In other words, Vendyl Jones is eager to begin another sequel.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Arlington