On the evening of August 27, 1908, dark clouds gathered over the Dry Cimarron River along the New Mexico–Colorado border. Sarah Rooke, the phone operator in Folsom, New Mexico, called as many people as she could to warn them about the impending storm, but it wasn’t long before water began pouring from the sky and rushing through the town, wiping away entire buildings in its path. More than a dozen lives, including Rooke’s, were lost in the flash flood that night.

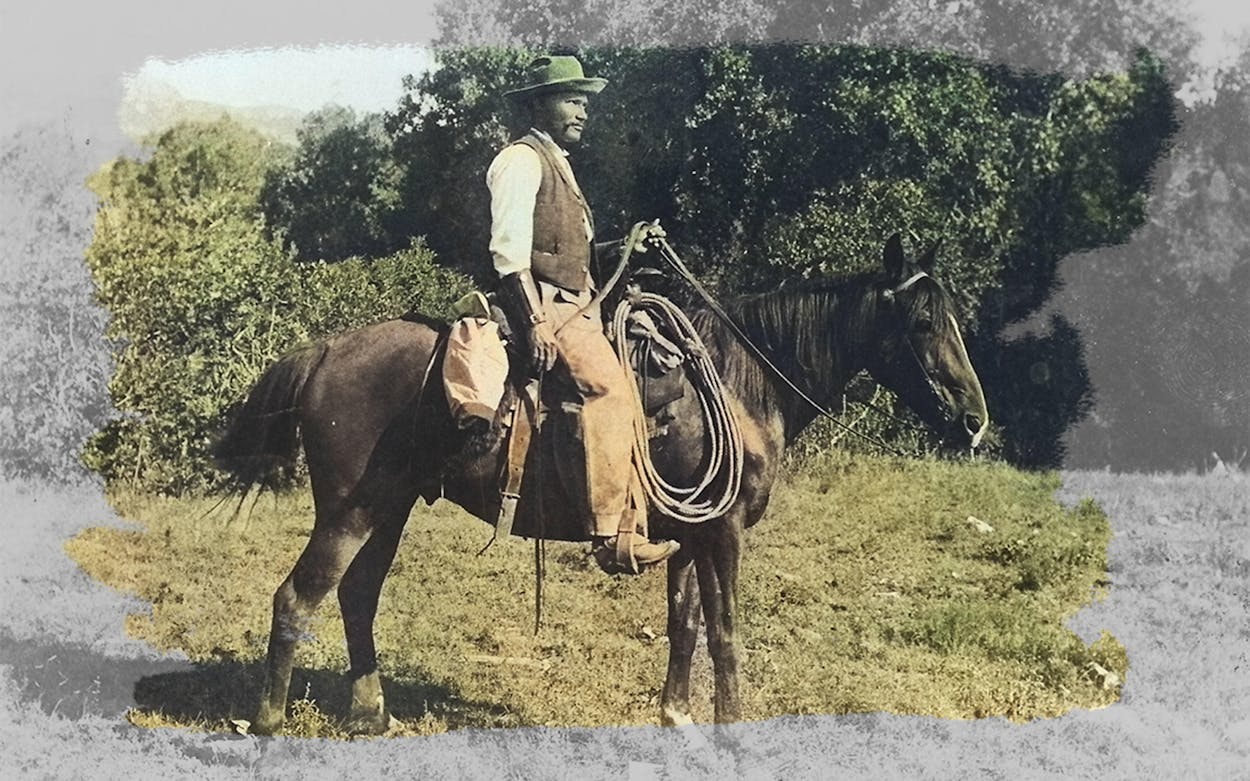

The next day, George McJunkin, a cowboy from Leon County, east of Waco, who worked as the foreman of a ranch near Folsom, took his horse out to survey the damage. As he trotted along the edge of a gully, which he called Wild Horse Arroyo in honor of the horses he broke there, he spotted something unusual sticking out of the soil. An amateur naturalist with an enthusiasm for collecting peculiar items, McJunkin hopped off his horse and walked ten feet into the washed-out land to get a closer look. As he approached the white object protruding from the arroyo, he realized he was looking at animal bones that had been uncovered by the heavy rain. Scanning the remains, he noticed that they weren’t normal cattle or bison bones—they were much bigger than anything he had ever seen before. He sensed that he had discovered something of great magnitude. Although McJunkin would die before anyone could confirm his suspicions, he was standing in what archaeologists later dubbed the Folsom Site, a plot of land laden with crucial specimens from a huge, prehistoric bison species. These bones eventually ended a long-standing anthropological debate, proving conclusively that humans had lived in the Americas since at least the end of the last Ice Age.

According to Franklin Folsom’s Black Cowboy: The Life and Legend of George McJunkin, the most extensive, albeit secondhand, account of McJunkin’s life, he was born into slavery in 1851 on a ranch in Rogers Prairie, a small community that was about halfway between Dallas and Houston. Like many enslaved people in Texas during the Civil War, McJunkin took on the responsibilities of local white cowboys who left to fight for the Confederacy. Since his father was a blacksmith and the white cowboys weren’t around to teach him the basics, McJunkin darted down to a nearby ranch, where Mexican cowboys taught him how to wrangle a horse.

On June 19, 1865, or Juneteenth, Union soldiers arrived in Texas and told enslaved people that the war had ended and they were free. But though fourteen-year-old McJunkin dreamed of leaving the ranch and becoming a professional cowboy, he stuck around to help his father in his blacksmith shop. After a few years, McJunkin finally left the ranch and took off in search of work as a cowboy. Just outside of Comanche, he met a trail boss who hired him as a wrangler; McJunkin also helped a trail cook prepare meals. Later, a former slave owner from Georgia named Gideon Roberds hired him to train horses to sell on the Santa Fe Trail. McJunkin traveled with Roberds and his crew through Texas, stopping in the Palo Duro Canyon, and finally settled in New Mexico. On the Purgatoire River, just east of the town of Trinidad, Colorado, he helped the Roberds family set up a ranch outfitted with a schoolhouse for their children. According to Folsom, McJunkin traded the children riding lessons for reading lessons, borrowing their textbooks to teach himself at night.

McJunkin quickly established a reputation for his horse-handling skills, and soon other ranchers started seeking out his services. Eventually, Dr. Thomas Owen, a former officer in the Confederate Army and the first mayor of Trinidad, hired McJunkin to work on his ranch near the Dry Cimarron. McJunkin unexpectedly found himself in charge of the ranch after Owen fell ill and died, leaving behind his wife and two young boys. By the time of the devastating storm of 1908, McJunkin had taken a job just a mile away as the foreman of a ranch, where he built his own cabin and owned a few head of cattle. Everywhere McJunkin settled into a room of his own, he displayed a set of objects, including crystals, rocks, and bones (even a human skull, according to Folsom) that he had collected during his travels.

“He was naturally inquisitive,” says Michael Grauer, the McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. “That desire to know things and to further his education and improve himself as a person drove his collecting.” This trait seems to have helped McJunkin to understand what he was seeing in the arroyo. After the discovery, he attempted to stir up interest in what he called the Bone Pit, even writing to a man in Las Vegas who he had heard was interested in bones. But no one ever came to look at the site before McJunkin died in 1922 at age 70 or 71 (his birthdate is lost to history).

A few months after McJunkin’s death, Carl Schwachheim, a blacksmith from Raton, forty miles northwest of Folsom, traveled to the arroyo to take a look at the bones. There is no written record proving that McJunkin had informed Schwachheim of his discovery, but Folsom, McJunkin’s biographer, writes that he tracked down Schwachheim’s sister, who reported that McJunkin had visited her brother. As the story goes, McJunkin was traveling through Raton when he required the services of a blacksmith. He found Schwachheim’s shop, where he noticed a pair of elk horns on display at the top of a fountain in front of the entrance. The two men got to talking about bones, and McJunkin, recognizing a kindred spirit, revealed the story of the Bone Pit. When Schwachheim finally decided to make the trip to Folsom, he recruited Fred Howarth, a banker who had an interest in bones and owned a car, to join him. They rounded out their crew with their friend Charles Bonahoom and Father Roger Aull, a local Catholic priest. The group found the pit, removed some bones, and carried them back to Raton, where the remains stayed until 1926. That year, Howarth and Schwachheim traveled to the Colorado Museum of Natural History (today the Denver Museum of Nature and Science), where they notified the museum’s director, J.D. Figgins, and paleontologist Howard Cook of their findings. Later, Howarth sent some of the recovered bones to the museum. Upon receipt of the bones, Cook confirmed that the remains belonged to an extinct prehistoric species of bison.

Hoping to unearth more bones to reconstruct a bison skeleton, Figgins hired Schwachheim to dig at the site. Before the 1920s, there was little consensus on how long humans had been in the Americas. Many scholars believed—with no real evidence, as radiocarbon dating had not yet been invented—that humans had been in the region for only three thousand to four thousand years.

“It was a guess. It wasn’t even an estimate,” says Steve Nash, senior curator of archaeology and director of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. “This was a convenient interpretation for [white settlers] because if you want to dehumanize or disenfranchise a group, you take away their historical connections to their land. You delegitimize their claim to their territory.” Others postulated that humans had roamed the Americas for much longer, perhaps more than twice as long as many researchers thought.

A year after Schwachheim started digging, he finally came across the smoking gun: a spear point lodged between two bison ribs. A group of paleontologists and archaeologists from as far away as the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian made the journey to the site and agreed that the weapon was evidence that humans had been in the region at the end of the last Ice Age, roughly 12,000 years before. “That brought decades of bitter controversy and dispute to an end,” says David Meltzer, a professor of archaeology at Southern Methodist University and the author of Folsom: New Archaeological Investigations of a Classic Paleoindian Bison Kill. Meltzer, who spent two years excavating the site in the late nineties, dedicated his book to Schwachheim and McJunkin. “Most cowboys probably would have kept riding, but to his ever-lasting credit, George got off his horse and went down into the arroyo to get a closer look,” he says.

McJunkin didn’t live long enough to receive any accolades for his work, but last year, his legacy was honored with an induction into the Hall of Great Westerners at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum. According to Grauer, inductees must express independence, fortitude, and “a great deal of perseverance.” “Most cowboys were pretty anonymous,” he says. “They did their work, they lived their lives, and they went off into the sunset.”

In Grauer’s view, McJunkin was exceptional, and not just because he uncovered an archaeological site. For a Black man to rise through the ranks to foreman in the early twentieth century was virtually unheard of, according to Grauer. Although McJunkin’s name is remembered today because of his discovery, it was everything he accomplished before and after that distinguished him as a great Westerner.

- More About:

- Texas History