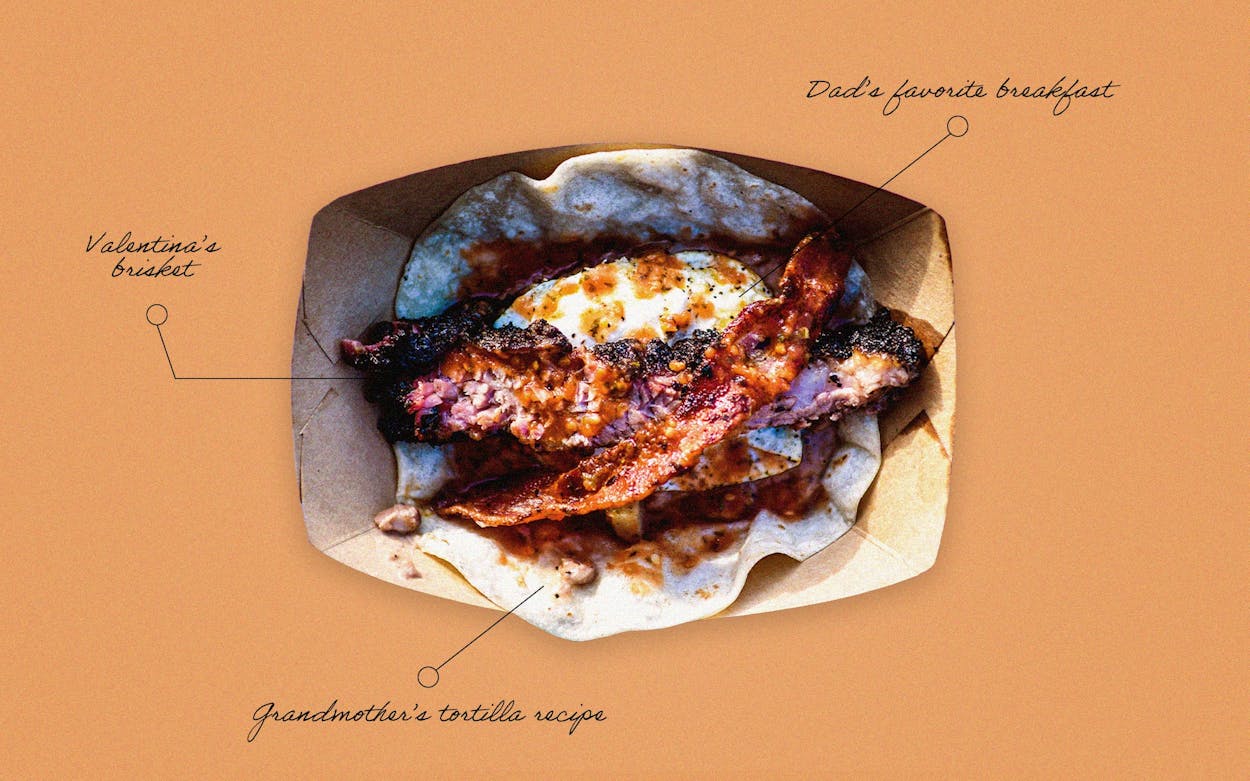

At Valentina’s Tex Mex BBQ in Austin, the Real Deal Holyfield isn’t just a breakfast taco. It’s an expression of personal history for owner Miguel Vidal. His dad’s favorite breakfast (huevos rancheros) served on a homemade tortilla (just like his grandmother made), topped with a slice of brisket (from his beloved barbecue restaurant) and named after a line from a Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg song that came out when he was in high school in San Antonio. At Roots Southern Table in Farmers Branch, Top Chef alum Tiffany Derry serves her mother’s gumbo with hot-water cornbread, creamed-corn ravioli and duck fat–fried chicken, a nod to both her Southern roots and her culinary training in Europe.

As a longtime food writer, I’ve long appreciated the ways that a dish can tell a story. My job isn’t just covering flour and sugar and butter—it’s to learn about and share the way a family can write its history bite by bite, or the role food can play in ancestral healing, themes many of us can relate to through the lens of our own meals.

Foods like the Real Deal Holyfield and Derry’s gumbo have a strong sense of place, which means much more than the physical building where the food is served. Instead, it’s about the emotional connection between the dish and the person eating it. If a diner knows the story behind the taco or the gumbo or the fried chicken, she is far more likely to see a part of herself in the chef. That bond creates a feeling of belonging or familiarity—or, as it’s known in postmodern terms, a sense of place. Even after all these years writing about what we eat, I never thought about food as a portal to a sense of place until I stumbled upon an article about the late architect Charles Moore.

Moore, who taught at the University of Texas at Austin from 1985 until his death in 1993, is the pioneer of placemaking. One of his most influential contributions, placemaking is a tenet of postmodernism—a design philosophy that, generally speaking, shifts the focus from form to function. Although Moore never applied his principles to dining, I immediately made the connection to what I now think of as postmodern food.

Modernism in food brought us molecular gastronomy, a type of cooking that prioritizes novelty over nostalgia and science over history. It brought us experimental dishes like carrot air and spherified olives. The chefs at the helm of modernist cuisine make the case that traditional foodways don’t challenge us enough, and seek to surprise the eater with an unfamiliar dish or unexpected element. In contrast, postmodernists could say that abstracting food from its familiar form only removes us from the experience of eating it and the meaning it can hold. To put it another way: Modernists are beholden to no traditions. Postmodernists embrace them.

Moore penned a number of essays over the years about his postmodern design theories, but it was his five principles of place that made me realize the postmodern food movement is well upon us.

In the essay “Toward Making Places,” Moore writes that creating a sense of place requires a handful of inputs: processional axes (orientation and relationship), boundaries (demarcation), landmarks (signature elements that impart geographical context and history), and, most importantly, a sense of connection. If buildings can reflect culture, history, ancestral lineage, and the relationship between the object and the user, why can’t food?

When it comes to cooking, we are all architects with the opportunity to give food its own sense of place. Applying Moore’s five design principles to food helps us better understand how to eat mindfully:

1. “Bread cast on water come(s) back as club sandwiches.”

This is Moore’s way of saying that what we put into buildings (or our next meal) will come back amplified and augmented, as long as we believe that they are worthy of our effort. If a building can receive, store, and return the energy and care of its occupants, then so can a pantry or a pile of Grandma’s recipes.

I love Moore’s bread metaphor. During the panic-buying stage of the pandemic, flour suddenly became something worth our effort, and millions of people baked bread for the first time. With our hands, we transformed something mundane into something special. Thanks to heirloom-grain growers across the region, restaurants like Petra and the Beast in Dallas, Nancy’s Hustle in Houston, and Cochineal in Marfa are serving varieties of wheat that early Midwestern farmers would have grown. The amount of effort going into their metaphorical club sandwiches has never been higher.

2. “If buildings are to speak, they must have freedom of speech.”

Office buildings, houses, and retail and public spaces are in constant dialogue, and so are home cooks, diners, farmers, and chefs. That doesn’t mean they always agree. At Old Thousand in Austin, owner Ben Cachila serves brisket fried rice and five-spice churros that reflect his Gen X, Asian American experience. The food is in no way authentic or traditional, but that’s not the point. The dishes may not be to everyone’s liking, but that doesn’t mean Cachila shouldn’t serve them.

3. “Buildings must be inhabitable by the bodies, minds and memories of humankind.”

Buildings connect us to our humanity and to our history. People who live in a building (and who cook food) can imprint their lives onto that building (or that meal). Christine Ha and Tony J. Nguyen of Xin Chao in Houston serve their rice-crusted, buttermilk-fried chicken with beef-tallow aioli—a dish entirely of their own invention, but inclusive of many points of reference to foods they grew up eating as second-generation Vietnamese Americans. The restaurant’s egg rolls are, quite literally, a combination of both Christine’s and Tony’s mothers’ recipes.

4. “Our architecture needs to remember [cardinal points in space], too, so that we can feel with our whole bodies the significance of where we are, not just see it with our eyes or reason it out in our minds.”

As humans living in a particular space or consuming a specific meal, we might not consciously think about up and down, salt and sugar, inside and outside, hot and cold, but we perceive these things nonetheless. Having coffee every morning, for example, is a cardinal point in my day. Without it, I would feel disconnected from my own sense of place.

5. “The spaces we feel, the shapes we see, and the ways we move in buildings should assist the human memory in reconstructing connections through space and time.”

This is my favorite principle from Moore because it relates to what I think food is ultimately about: connecting with our roots, and cooking with our ancestors and earlier versions of ourselves. At Damien Brockway’s aptly named barbecue trailer, Distant Relatives, the former fine-dining chef serves comfort food inspired by flavors from the African diaspora, including a side dish made with burnt ends and black-eyed peas that is a clear nod to his ancestors’ resourcefulness and agricultural acumen in the face of enslavement and dispossession.

Until reading Moore’s principles, I’d never considered how a building could make me feel, but now I can see how good design—just like a favorite meal or one that’s rich with story—makes us feel comfortable, connected, and protected.

My son recently started making the same Dagwood sandwiches that my mom used to make and that her mom used to make—potato chips and all. When he crunches down with that first bite of turkey, pickles, cheese, and that spongy, store-bought sandwich bread, my mom, dad, and grandmother are suddenly in the kitchen with us, looking at the clock to see if it’s time to start Days of Our Lives.

Now, whenever I look at a menu, I search for clues about the history, geography, and ancestry that give dishes such a strong sense of place. The next time you sit down to a meal, I suggest you get curious about why the chef made the choices they made; what ingredients they used and why. Listen for those “memories of humankind” that Moore knew could live in buildings, too. When you’re in charge of making dinner, think about your own sense of place. How does food help you better understand your own evolution to get to this very kitchen in this very home in this very place where you live?

- More About:

- Architecture