This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On December 27, 1972, in a disaster comparable only to the Dallas Neiman-Marcus Christmas fire of 1964, one of Houston’s cherished institutions nearly burned to the ground. The fire almost ruined the holidays for families in River Oaks, where women still speak of having felt “completely abandoned” and “unable to cope.” Two months later the restored building, filled with floral arrangements and congratulatory letters from friends, reopened to a huge crowd of well-wishers, many of whom had joked, half-seriously, for days about what to wear to the grand event. The occasion was not the reopening of Saint John the Divine Church or the River Oaks Country Club, but of a grocery store—Jim Jamail and Sons Food Market, 3114 Kirby Drive.

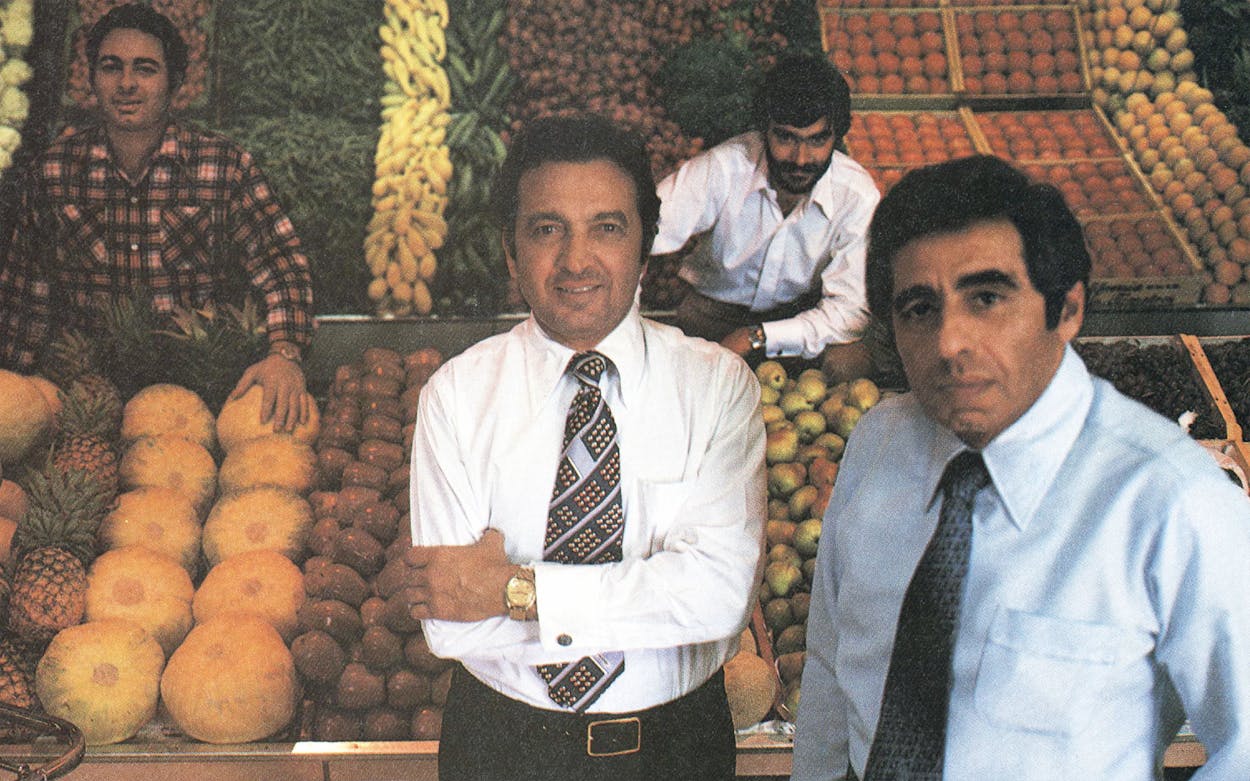

Jamail’s is a grocery store so famous for its service and the quality of its food that for over thirty years it has relied on its customers for publicity and has never run a special or paid for an ad. Nageeb “Jim” Jamail, the founding father of the store, began selling produce to the carriage trade from the stalls of Houston’s old City Market in 1905, a time when Houston City Hall was on the second floor of the market. He made his reputation selling the freshest, choicest produce at fair, if not inexpensive, prices. Before World War I, he had expanded his business to include leasing produce stands in the new chain stores. Then, in 1946, when his three sons Joe, Albert, and Harry came home from the war they opened a store on Montrose, which offered a little friendly competition to some of their relatives, the Jamail Brothers Food Market on Shepherd. By 1959, their own growth and that of Houston (Southwest Freeway was plotted to run right through their doors) forced them to move. They then built the Kirby Drive building, which they enlarged in 1967, and are in the process of enlarging again.

Shopping at Jamail’s is a Houston family tradition passed down through generations. As one young River Oaks housewife says, “My grandmother remembers shopping at Jim Jamail’s stalls and still thinks she has to remind me that even though I may pay more for a head of Jamail’s lettuce, I will be able to use the whole head. Heavens, I wouldn’t shop anywhere else. My own daughter begs to go there because they give her free bananas and Frogurt, and I can never resist buying her one of their nickel Cokes.” another young lady informed me with the hauteur of a DAR, “Of course, my family has been trading with the Jamails long enough to be old customers—you know, the ones they give free Christmas trees.” The tradition of the best people shopping for the best food at Jamail’s goes far beyond Houston’s city limits. Mail or phone orders come in regularly from Europe, Canada, and Mexico. Jamail’s sends produce by bus to nearby Texas towns like Austin and airfreights special items, such as fresh caviar and salmon, to cities all over the United States. They have been known to supply the White House with special orders and they still see that Lady Bird stays well stocked out on the ranch.

The first time I visited the store was on a sleepy September Saturday morning. I easily maneuvered a deserted Southwest Freeway, slipped off on the Kirby Drive exit, and was driving casually north a few blocks when I nearly had a rear-end collision in the traffic jam of shoppers trying to turn into Jamail’s parking lot. Jaguars and Mercedeses, Rolls-Royces and Cadillacs, as well as a few Pintos and Rabbits, were jockeying for positions in the horseshoe of parking places stretching around the front of the store. Once out of the race, I got my first disappointing view of the store. It looked exactly like my neighborhood Safeway. As I joined the crush of people heading for the entrances mumbling among themselves that they were crazy to shop Jamail’s on Saturday, I nodded to each that I thought they were right.

Inside, my anxieties lessened. The first thing I saw was a portrait of the late Jim Jamail. It is impossible to imagine the dignified-looking Lebanese man in the picture as the founder of a Safeway and, indeed, the minute I looked past the portrait, I saw that the quality he stood for is still very much in evidence.

The store is well designed, with wide aisles spaced to allow an excellent view from front to back and across the store. The counters are low and everything is in easy reach. There are no banners, streamers, or aisle labels flapping from the ceiling, no Day-Glo shelf posters blaring two for the price of one, no tacky displays of everything you don’t want for “Cookout Time,” and no six-foot-high stacks of canned tomatoes to overwhelm you as you round the corner to another aisle. Best of all, there is no huge line of stuck-together shopping carts that must be grappled with before you can even begin to shop. If a cart is not handed to you in person by one of the Jamails, you can find one in the inconspicuous, but convenient, spot where they are kept. At the checkout counters there are no trading-stamp dispensers, no candy and gum racks, no National Enquirer stands (in fact, no magazines at all). Checks are speedily okayed by a Jamail right at the counter for those customers who do not charge.

A Houston friend once told me, “People in Houston don’t talk about food without mentioning Jamail’s, and people don’t talk about Jamail’s without praising their vegetables and fruits.” After seeing the produce department that is a statement I do not care to dispute. An actual cornucopia of fruits and vegetables tumbles out from under a shelf of wicker baskets onto sloping counters lined with white butcher paper. There is row after perfect row of vine-ripened tomatoes, Kentucky limestone Bibb lettuce, snowy cauliflower, crisp watercress, baby snow peas, glowing eggplants, leeks, Belgian endive, fresh Kentucky mint, shallots, California avocados, raspberries, mangoes, and wooden baskets lined with French blue tissues filled with beautiful mushrooms. Each fruit, each vegetable is perfect, the absolute best money can buy.

“Jamail’s will airfreight meat, fish, fowl, and cheese all over the world. ‘We can get anything anyone wants. We’ve found everything for our customers from ptarmigan—a bird that lives above the timberline in Finland—to elephant meat.’ ”

It is the best because Harry Jamail, the youngest of the three original sons, and Jim Jamail, Joe’s oldest son, go to the Houston produce market at 4 a.m. three days a week to handpick the finest produce available. As Jim says, “If we want thirty crates of cantaloupe, we open and check thirty crates of cantaloupe at the market and we double-check thirty crates of cantaloupe when we unpack them back at the store.”

The Jamails demand not only that the produce be of the finest quality, but also that an exhaustive variety be supplied year-round. They keep a produce broker on retainer in Los Angeles to rush them by truck the items they can’t find in what Jim calls “Houston’s notoriously bad produce market,” and they import rare foreign produce by air. One loyal customer rather daffily insisted, “At Jamail’s it is always July.” Another: “I have found cherries in mid-December, perfect pecans during the pecan shortage, and poblano peppers the day my Mexican maid said she’d cook.”

Produce trucks arrive at the store at 6:30 each morning. The items that are not placed immediately on the counter are kept in storage lockers at precise temperatures. The first locker is between 38° to 42° for potatoes, melons, peaches, apples; the second, at 46° to 47° for citrus, tomatoes, avocados; the last, at a damp 42° for lettuce, brussels sprouts, carrots, and celery. Watching Jim Jamail put the produce away I got the feeling that if vegetables were children, he would tuck them in each night with teddy bears. Next, Jim brings out and again checks the produce that has been stored overnight. A dozen people could have breakfasted on the strawberries he discarded into the old oil-drum trash can from yesterday’s pints because he deemed them no longer in perfect color. The staff then puts the produce out on the counters. The sixteen produce people are all trained to arrange the different fruits and vegetables artfully with an eye for color, texture, and compatibility of taste. Their finished product looks like a Dutch still life and they treat it with about as much respect.

The produce looks fresh because it is fresh. The counters aren’t refrigerated, and no one squirts the lettuce with water to perk it up. There’s not a brown spot on a pear, because customers look, but don’t touch. The produce attendants pick the produce for you. If you want a particular basket of blueberries or need a specific size of bell pepper they are happy to oblige. (Actually, no one will slap your hand if you do touch the forbidden fruit, but it is as frowned upon as taking a bite of a peach and putting it back would be in another store.) The produce people can pick an avocado perfect for guacamole that night or, if you prefer, select one that will ripen in precisely three days. They are generous with their knowledge, advising customers on how to select produce, how to use it best, and how it should be properly stored.

The service is fast—I watched them go from customer number 21 to number 88 in less than one hour—and the number of the customer being served is posted to let you know if you have time for a quick run to the frozen-food counter. You can also leave a list with the attendants, do the rest of your shopping, and have your produce waiting for you when you check out. If you are in a hurry or need just a few items you can head for the west end of the produce area where there is express service. Frankly, only a screaming child could make me rush, because the produce market is the social hub of Jamail’s. It is a salon, if you will, where the elite of Houston and their maids gather to make polite conversation with strangers and to gossip with friends. The people watching is superb. One matron, elegantly dressed but completely wilted, was trying to finish her grocery list while she waited, but before her number was called she had agreed to so many new committee meetings that her list of new obligations was longer than that of the food she had come to buy. Two young decorators met and began passing the time complimenting each other’s respective “good taste,” but by the time they were served they were in a cat fight that ended with one accusing the other of not knowing the difference between a Fabergé egg and the eggplant he had just been handed.

If the produce department is Jamail’s salon, the meat department, at least on Saturdays, is clearly the den. Here people were waiting three- and four-deep to be served and most of them were men. One gentleman rushed in to pick up seven ounces of fresh caviar for $60. Another man sat on a stool fussily selecting choice luncheon meats to be wrapped for a picnic, while his wife went off to choose the paper plates. There was a lot of football talk and laughter in front of the huge counter, which runs almost the full length of the back of the store, and plenty of entertaining action behind the counter, where nothing comes prewrapped. The butchers were busy sectioning plump fresh chickens for frying, cutting pockets in lamb shoulders, grinding beautifully marbled beef, slicing medaillons of white Minnesota veal, and wrapping paper-thin slices of prosciutto, all while live lobsters put on a show of their own.

The number system isn’t used at the meat counter because over the years most people have claimed one of the eighteen butchers as theirs and prefer to wait for him, no matter how busy he is. The butchers shout greetings to their customers as they spot them in the crowd and they know the regulars by name. Says Arnold Kitzmiller, head butcher for 27 years, “My first business is meats, my second business is names.” The butchers know who likes his sirloin strips cut exactly three inches thick, who is on what diet, who must have fresh escargots, and who ate what meats last week. They can remember all this, hand out pieces of cheese to children without missing a child, and, at the same time, keep a bawdy banter going among themselves. Each one has managed a butcher shop or department before ever coming to Jamail’s, and, of the butchers I talked to, the one with the shortest tenure had spent eleven years behind this particular counter. The butchers are also skilled fishmongers. As one young working woman raved, “I never miss the days the fresh lemon sole comes in. It’s extravagant, but I never overbuy because my butcher tells me just how much I need. Besides, it’s worth it just to watch him—nobody can do a better fillet.”

It is demanding work. During holidays they work two or three extra hours on either end of the regular store hours from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. They package and airfreight meat, fish, fowl, and cheese all over the world, they cut any order to any specification, and they fill orders of any size. Regular Houston customers depend on the Jamail butchers to provide them with a ready supply of frozen game for those quail dinners when the hunter comes home short or to deliver another beef tenderloin in an emergency when the one they bought just won’t be enough. Jamail butchers have, in fact, taught at least one Southern belle to cook. “They saved my marriage. I broiled the biscuits the first breakfast I cooked. I learned everything here. Other stores seem like Yankeeland after growing up at Jamail’s.”

“We can get anything anyone wants,” Kitzmiller claims. “We’ve found everything for our customers from ptarmigan—and I bet you don’t even know what that is; it’s a bird that lives above the timberline in Finland—to elephant meat.” One year they airmailed four pounds of fresh lox to a Florida man for New Year’s Eve for a cost of $108, including tax.

Arnold tries to keep a $40,000 to $50,000 inventory on hand at all times, and to do this he must refill the lockers two or three times a week. He buys from four Houston packing houses and maintains quality and freshness the same way the produce department does: he handpicks the meat, stamps it with the Jamail stamp, then rechecks it when it is delivered. He keeps careful track of the meat after it enters the store by rotating it through his two meat lockers to make sure it is served at optimum age. Beef, for example, is at its prime when it has been aged in lockers for 21 days. As Arnold said in a conspiratorial whisper, “You know, some people just have to have the best.”

Although it may be stretching it to refer to the produce section as a salon or the meat counter as a den, even the Jamails call the prepared-foods department the kitchen. The first area you come to is the cheese cases, which, along with the spice racks, is a meeting place for Houston’s Europeans coming to select ingredients for their most exotic dishes. Here a charming lady with a German accent tries to educate the palates of native Texans. This Saturday she was serving French fontina and Dorman’s imitation “healthy” Tilsiter cheese from a brass compote, but she was doing her best business in good ole rat cheese. The prices throughout the huge cheese section were pennies cheaper than I had found in other stores, but most people’s savings were quickly spent on the nearby petit fours and baklava, which are made in Houston especially for Jamail’s.

Through the back of the cheese department you can get a glimpse of the Jamail in-house kitchen, which chef Rolf Meitler has commanded for ten years. From here come the imaginative, exquisitely prepared gourmet meals he concocts for Houston parties, large (4000 or so for the International Bankers Convention) or small (12 for the Seventh of April Club, a Houston gourmet group). Picnic baskets, Lear jet lunches, and the executive dining room menus of Houston corporations are prepared here, and this is also the place, so Houston gossip has it, where one of the city’s best-known caterers gets “his” food, which he delivers after tacking on his percentage. All the prepared food can be ordered from printed lists. One is a weekly menu offering a choice of four soups, sixteen entrees, and three vegetables for each day without duplicating a single dish. Another is a selection of party foods with over forty different kinds of hors d’oeuvres, ranging from celery hearts with salmon mousse to oysters Rockefeller, and a complete assortment of finger sandwiches, canapés, cheese balls, dips, vegetable trays, fruit boats, and cold cuts; you can even get a decorated roasted suckling pig. On top of this, Meitler runs a fantastic gourmet deli where you can buy anything from a sliced turkey sandwich to a four-course meal. Or, as one woman suggests, “You can just keep an eye on the deli and lift chef Meitler’s latest cooking ideas.”

The “kitchen” is now being expanded, and I couldn’t help feeling pleased that the extra room would be going to chef Meitler. Where would the Jamails ever find another man who says, “Sometimes, yes, it is hard. A lady comes in at five p.m. and says, ‘Rolf, you must help me. We just flew in from Japan and are having eighteen for dinner in two hours.’ So I run around the store and get things for her from the kitchen, from the freezer, from the shelves. Then I stay in touch with her maids and butler to help them prepare. Then when I go home for my dinner, I tell you, I am ready for a hamburger.” He convinces you not only that he cheerfully does this, but also that he would do it for you just as enthusiastically. Actually, he already has. The frozen-food counter contains delicious samples of his food repertoire from Lebanese lentil soup to cannelloni bolognese to lemon soufflé with raspberry sauce.

The catered, deli, and frozen foods are expensive, but the customers I talked to were willing to pay the price because it all tastes wonderful and it is convenient. One woman takes her own casseroles in to be filled with a Jamail’s lasagna. She pulls them bubbling hot out of the oven at dinnertime and swears not even her husband knows the difference. Another hostess who is partial to giving Sunday brunches takes her silver platters to Jamail’s to be filled on Saturday, but, even though she has two refrigerators, she doesn’t have enough room to bring all the food home that day. Her solution to this dilemma is to have one of the Jamail brothers get out of bed, open the store for her at 7 on Sunday morning, and help her load the trays into her car. She told me, “The Jamails do such lovely things and have such lovely manners.”

I had already asked one of the Jamails what happens to all the food, meat, and produce that is no longer quite fresh enough to sell the next day. He assured me that the store had a liberal discount that lets employees enjoy the best too. When I asked chef Meitler the same question he reminded me that the Jamails are a very large family with lots of mouths to feed.

It is almost impossible to round an aisle without running into a Jamail. Joe, the oldest son, is the manager of the “front” of the store and the one who handles the customers. The day I was there he did everything from make the famous Jamail fruit baskets to check out groceries and okay checks. He might have even beat out Arnold Kitzmiller if I had kept count of who called the most customers by name.

Albert, the next oldest, manages and buys the groceries for the rest of the store. He was the one who explained to me the deceptively simple Jamail philosophy of how to run a grocery store: “One must maintain a small-store atmosphere within a complete food market.” In other words, Albert is responsible for keeping Jamail’s small enough to insure superior service and quality, yet large enough to carry everything their customers might want.

The Jamails provide this service and quality first by having a member of the family or a surrogate like Arnold Kitzmiller or Rolf Meitler oversee every facet of the store’s operation. Second, they employ 135 workers on each single-shift day (a typical store of this size might have 60 employees working at one time on its busiest day). According to Albert, the family chooses employees on the basis of how “nice” they seem. And the Jamails’ personnel maxim is that if you treat employees politely they will be polite to customers in turn. They are paid well, not transferred from store to store as in the large chains, and do not work early and/or late shifts. As a result, there is always a pleasant clerk to lead you to a product you can’t find, instead of pointing you to aisle 17b with a surly grunt. There is someone eagerly waiting to unload your basket at the checkout stand with the prices facing up so the checker can read them quickly, making the process so fast that it is as easy to drop in for a loaf of bread at Jamail’s as at a Seven-Eleven. You may come into Jamail’s, select your groceries, and have them delivered to your home. Or, if you do not have a way get to Jamail’s, someone will pick you up and bring you in the courtesy car to the store.

Stocking all the merchandise one of their customers might want is at once difficult and easy. Jamail customers come in looking for everything from fresh crab claws to bathroom cleanser, but they do not come in expecting to buy encyclopedias, panty hose, or china. Last spring, Albert tried to cut down on the number of items the store carried by asking the grocery staff to pull anything they thought didn’t sell well. After the inventory of 18,000 items, they found only 15 that the clerks were sure not a single customer bought.

Jamail’s is keeping up with the consumer demands of a growing Houston not only by stocking more imported foods and cooking ingredients, but also by making a special effort to get products that new Houston residents might have been able to get only in their old hometowns. Recently, Albert convinced Stouffer’s to supply Jamail’s with a French bread pizza that it was testing only in East Coast markets, but that a new customer missed. He stocks small-sized cans for single customers, as well as foods in all stages of preparation—for example, fresh pasta to dried. Jamail’s also has everything that might be needed for entertaining: Lenox candles, attractive paper napkins, a good selection of domestic and imported wines, everything except liquor, and, oddly enough, ice. Albert also carries food for people with special demands, like gourmet freeze-dried backpack foods and all the items on the Methodist Hospital’s low-cholesterol diet. Albert buys from the twenty or so grocery wholesalers in Houston and always purchases brand names, feeling his customers prefer them to foods processed by the same companies but bearing the Jamail name.

Jamail’s stocks a large variety of merchandise (over 230 flavors and labels of preserves, 200 of bread), making sure the items cover a wide price range. You can find Lady Borden vanilla at 55 cents a pint and Vala’s hand-packed brandy Alexander ice cream at $1.69 a pint. There are sixteen-ounce bottles of Heinz distilled vinegar at 34 cents and sixteen-ounce crocks of Ile de France oak-barrel-aged vinegar at $6.75. Jamail’s has six-ounce jars of B&B whole mushroom crowns at $1.39 and six-ounce cans of morel mushrooms Gyronitres au Naturel imported from Switzerland at $7.95.

The Jamails profit by spending on service and quality rather than on high overhead in their building or in expanding to new stores. They keep the rapid-turnover goods priced high: fresh mushrooms are $2.40 a pound; choice sirloin, $3.99 a pound; a deli salad of avocado and pineapple with poppyseed dressing, $2.15 a half-pint. But the rare merchandise that is in less demand is priced on par with the smaller specialty stores: fresh pasta is $1 a pound; Japanese dried forest mushrooms, $1.89 for 1 1/2 ounces; French Brie, $4.30 a pound. Ordinary items—orange juice, detergent, milk, canned coffee—I found to be a few pennies higher overall, but that somewhat surprised the Jamails. They try to keep ordinary merchandise competitively priced and make their profit by not running periodic specials or paying to advertise.

Whatever the fine points of the Jamail philosophy, the most important fact is that it works. They have not only survived as a family-owned store, they have also become a social institution. Pushing a grocery cart around the aisles of Jamail’s on Saturday has become the Houston equivalent of making the paseo around the plaza on Sunday in Mexico. On weekdays, the number of silver-caned dowagers or their maids and chauffeurs has diminished in direct proportion to their ranks still found in the homes of the neighborhood, but the traditions are sure to go on.

Some members of the third generation have other notions. Larry Jamail is currently more interested in carpentry than in minding the store. The family seems to be patiently waiting for him to outgrow it, however, and they speak encouragingly of him as having the best business mind of any of the grandsons. Jeff Jamail is said to be as interested in seeing a bit of the world as the inside of the store. But Jeff was working as hard as anyone the day I was there. Then there is Joe’s oldest son, Jim, who is already putting in as many hours as his father or uncles ever have in a family that has been known, during the hectic Christmas holidays, to sleep on cots in the back of the store. We were standing outside in front of the store when Jim, trying to justify the long hours and hard work to his wife, Kathy, and me, said, “Look, I mean that’s my name up there,” as he pointed proudly to the sign above the door: JIM JAMAIL AND SONS FOOD MARKET.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Joe Jamail

- Houston