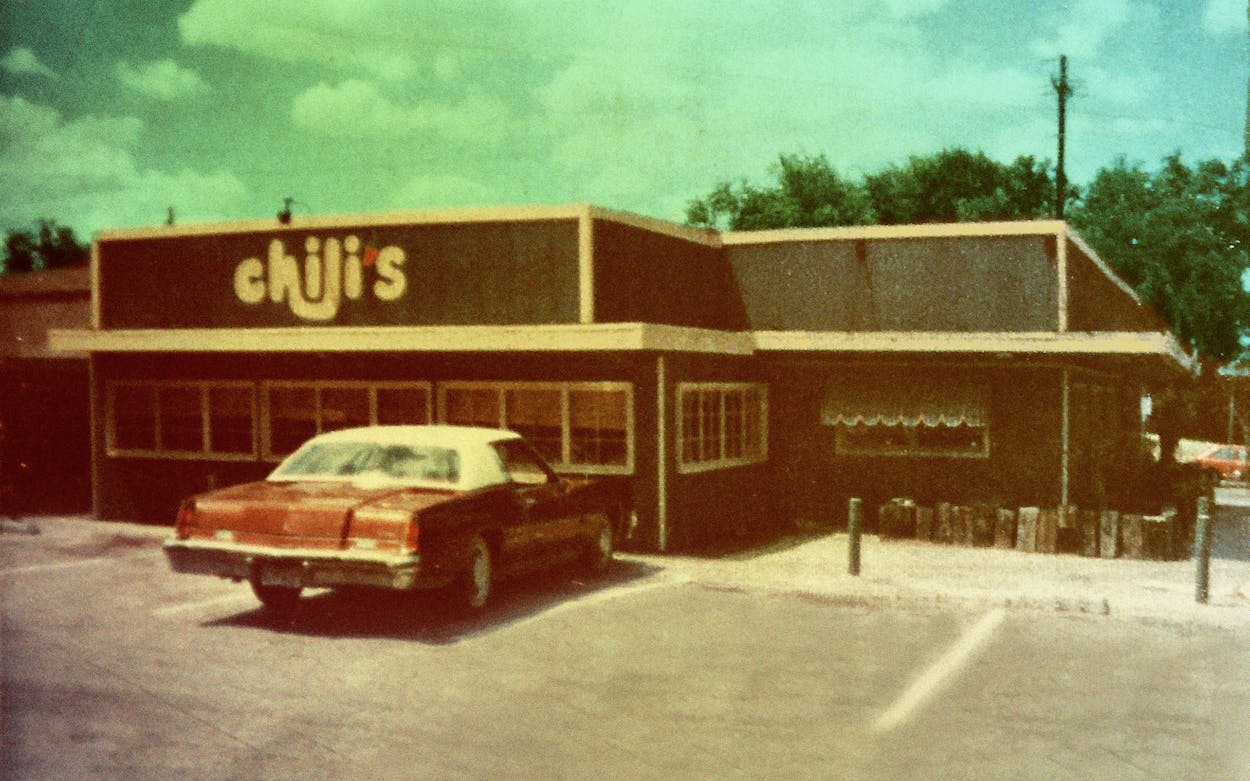

I mourned when the site of the first Chili’s location was razed. The building wasn’t much of a looker when it opened in 1975, at the intersection of Greenville Avenue and Meadow Road in northeast Dallas. It was a drab green with off-white accents and low ceilings. The original structure was replaced with a bigger building in 1981 after the city expanded Greenville Avenue right through the kitchen. That’s the one that was torn down in 2012. By then, the Chili’s had been closed for five years, but the restaurant chain was so instrumental in feeding my young family, I couldn’t help but feel a twinge of sorrow.

Around that time, my wife, my son, and I were living in Dallas’s Oak Cliff neighborhood. The nearest Chili’s was five miles away at Interstate 30 and Cockrell Hill Road. The kid was a challenging three-year-old with a finicky palate, which severely limited our dining options. That’s where Chili’s came in.

I did not want to go to Chili’s at first, but at some point you realize it’s not worth arguing with your child about where to eat. The food need only meet minimal sustenance standards, and the majority of the family must be happy. Seeing my son, who is now a teenager, beam with joy over a burger twice the size of his mouth made me happy.

Eventually, eating at Chili’s became something I looked forward to. It had something for all of us. I too went in for a “big, honking burger,” as my son described it. I ordered mine with bacon and cheese, while the boy liked his plain and dry. The various outlets where we dined were always busy, but being tucked away in a booth gave us a semblance of privacy, a moment’s respite from the the daily life of a young family. We craved predictability, and Chili’s offered that in abundance. To this day, when I drive past one of the chain’s 1,200-plus locations, I wonder what it would be like to take a break in that comforting and comfortable spot. This is by design, according to cofounder Larry Lavine.

In 1975, Lavine and his business partners were early to the casual, midscale dining niche that is so ubiquitous today “At the time, there were cafes and there were dinner houses,” says Lavine, now 78. “There wasn’t much in between. There was [TGI] Fridays and a few Steak and Ales. [Note: those are also Dallas-based chains.] There weren’t many casual restaurants.” Lavine’s venture had to be fun and approachable, with burgers and fries and chili front and center. The restaurant had to be nice enough that potential customers felt confident taking a first date there. It was good enough for former Dallas Times Herald arts and entertainment editor Don Safran. Every time he wrote about the restaurant, sales jumped, Lavine says. He and his partners found an underserved market, something that could arguably only happen in Dallas.

The city doesn’t have much going for it when it comes to the outdoors. There are no mountains or beaches. There aren’t many hiking trails, forests, or streams. We have malls and a lot of restaurants. Dining out is one of the many ways Dallasites entertain themselves. Plus, Dallas has long been home to more corporate and regional headquarters, and therefore to more transplants from other parts of the U.S., than most Middle American cities. Thus, grew the city’s reputation for incubating chain restaurants. “If your concept will work in Dallas, it’ll work anywhere,” Lavine says.

Chili’s—with Lavine’s business acumen, good food at a reasonable price (the original menu had a burger at $1.50), and an easygoing vibe—provided a template for other midscale restaurant chains. While Austin is home to a beloved Chili’s outlet, the chain is uniquely Dallas. When you eat at a Chili’s in Dallas, you’re eating local (Chili’s remains headquartered in Dallas). And if your idea of local dining includes all of Texas, well, eating at the Chili’s on 45th and Lamar in Austin is also supporting local.

There is something else that endeared me to Chili’s. Larry Lavine left the chain in the hands of Norman Brinker his Dallas-based firm and Brinker International in 1983. However, Lavine didn’t leave the restaurant business behind. He was an initial investor in Taco Stop, a walk-up, cash-only taqueria in the Design District of Dallas opened by Emilia Flores in 2012. I visited regularly, as the place very much fit the mold of a welcoming casual restaurant. In 2015, I listed Taco Stop’s picadillo taco as one of the 120 best in the state.

During one of our conversations, Flores called Lavine a mentor and a friend. When Taco Stop closed during the COVID-19 pandemic, I received an unsolicited email from Lavine. The body of the text read, in part: “Last taco [bald male head with a tear Memoji] taco stop as good as ever.”

Dallas—and Texas—had lost one of its best taquerias. I was heartbroken. It wasn’t only the food or the vibe that made Taco Stop great; it was also Flores’s kind heart. Lavine believed in Flores until the end. That kind of support bolstered my love for Chili’s, even though Lavine was no longer associated with the company. I can’t go to Taco Stop anymore, but I can eat at Chili’s. For that, I am grateful.