This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

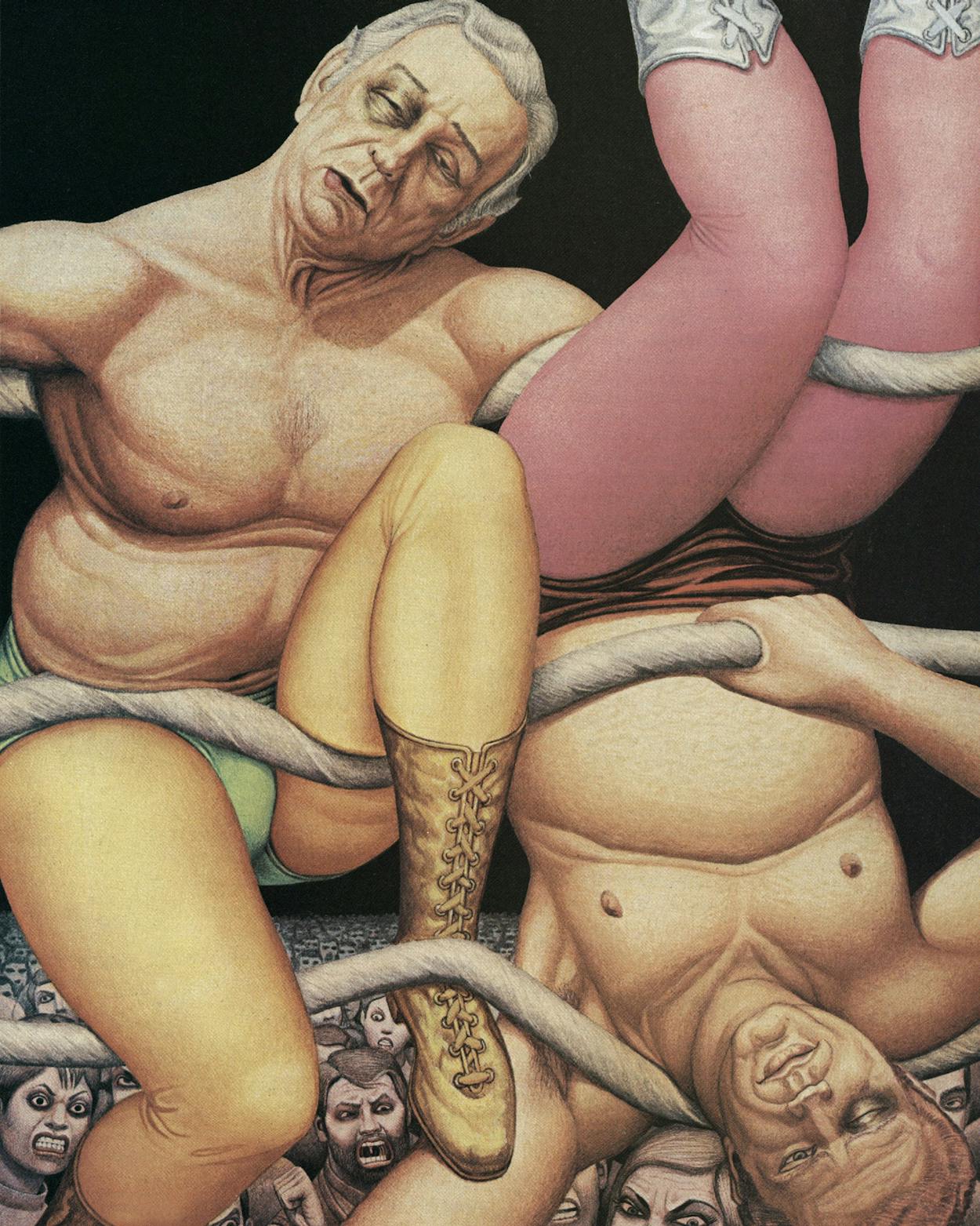

Of all the developers in the world, it would have to be Ben Barnes and John Connally who decided to build in my neighborhood. I had not seen much of Barnes, the former lieutenant governor, since he lost a bid for the governorship in 1972. But as editor of the liberal Texas Observer, I had written a jubilant account of his defeat, beginning with a verse of “Ding, dong, the witch is dead.” Over the years I’d penned some fairly tacky things about former governor Connally too. So when the two politicians-turned-developers announced their plans to build apartments just two blocks from my home in South Austin, I enlisted in the neighborhood army. This is the story of our first struggle. It began one long year ago, when I didn’t know the ABC’s of zoning law, when I was innocent of traffic-impact analyses, site plans, special permits, signalization criteria, and all the ins and outs of urban planning. For self-defense, I had to learn the rules of the real-life Monopoly game that is being played for high stakes all over the state.

Across Texas, people like me are battling rapid and inappropriate urban growth. The frontier credo that a Texan should be able to do anything he damn well pleases with his property is being challenged—although by no means vanquished—by homeowners who think that their local government is not protecting their interests. Austin, with more than 175 registered neighborhood associations, tops other Texas cities. In San Antonio the River Road neighborhood raised the first red flag in opposition to Clinton Manges’ plan to use Alamo Stadium for pro football. In unzoned, sinking Houston, a recent poll indicated that 66 per cent of the registered voters want a comprehensive zoning ordinance. The Williamsburg neighborhood in North Dallas, already plagued with well-nigh interminable traffic jams, has hired its own traffic engineer, as well as a zoning lawyer to fight further commercial development.

The oldest homes in my neighborhood were built in the early fifties, and many of the original inhabitants are being replaced by a second generation of owners. The residents are an amalgam of Anglos and Mexican Americans, blue collars and white collars. Lots of us are remodeling, and the neighborhood is looking better than ever before. Unfortunately, we are close to the central city, and builders are snapping up undeveloped tracts for apartment complexes, office buildings, and medical condos. Traffic is getting worse, and crime is on the rise.

“I was innocent of traffic-impact analyses, special permits, and all the ins and outs of urban planning. For self-defense, I had to learn the rules of the real-life Monopoly game that is being played for high stakes all across the state.”

Still, we’d never been inspired to protest until we found out about Barnes-Connally Investments’ scheme to build 344 apartments on a fifteen-acre rectangular plot that cut deep into the neighborhood. The property stretched west from the congested four-lane South First Street to South Fifth, a street used almost exclusively by the neighborhood. The apartments would be built across the street from an elementary school and would rub up against homes on three sides.

We got our first clue to Barnes and Connally’s plans when one of my neighbors stumbled upon a notice of a zoning hearing hidden behind a clump of weeds. He and all the other property owners within two hundred feet of the site subsequently received letters announcing Barnes-Connally’s request for a zoning change. The letters arrived on a Friday; the hearing before the planning commission was the following Tuesday. From the city we learned that about 10 of the 15 acres were zoned O, for offices and apartments. (We never learned how this acreage got its O zoning. Perhaps it had been obtained by the nursing home that once occupied the old stone building on the site.) The rest of the land, 4.29 acres, was zoned A, for single-family houses and duplexes. Barnes-Connally wanted the planning commission and the city council (it’s a two-step process) to change the zoning of that smaller section to B, which would allow apartments. We knew we had to fight the zoning change, but we didn’t know how to go about it.

A helpful soul in the city planning department explained to us that the most effective way to stop rezoning is to get the owners of 20 per cent of the property within two hundred feet of the site to sign a petition opposing it. When a group presents a valid petition, the zoning change must be approved by three fourths of the city council instead of the usual simple majority. That meant that two of the seven council members could keep Barnes and Connally from putting apartments on the A acreage. And we figured that we could count on at least two of the more liberal members to vote with us.

That weekend a number of people, including four who live on my street, canvassed the neighborhood, gathering signatures and urging residents to attend the planning commission meeting. Some people signed because they opposed all apartment construction; others didn’t want fifteen acres of green space to be bulldozed. Parents with young children were worried that the apartments would make the traffic congestion around the Molly Dawson Elementary School across the street even more dangerous. Another developer on South First had built some three-story apartments on a hillside, blocking the neighbors’ view of the city. This time the residents wanted to look carefully at the developers’ plans. Most alarming was the possibility that the city would want the project to extend Havana Street along one side of the planned apartments to South Fourth, which ends in a wooded cul-de-sac. Indeed, that turned out to be what the traffic planners had in mind.

Our debut at the planning commission was a lesson in city politics. If there had been no angry neighbors present that night, Barnes and Connally would have gotten their zoning change. Instead, the commissioners agreed to postpone the vote until the developers told us exactly what they intended to build.

I was out of town the first time Barnes and Connally’s representatives presented their plans to the group. At the second meeting, held in a law-firm conference room high in the big gold American Bank Tower downtown, the neighborhood was ready with some questions. Besides myself, our group included three students, two full-time housewives, a mid-level state bureaucrat, an architect, and a carpenter-contractor. Barnes and Connally were represented by Gary Davis, who was to oversee the construction of the apartments, and Jack Morton, a young attorney with Brown, Maroney, the firm hired to guide the project through the city-permit process. We had no sooner arranged ourselves around the polished conference table than Morton lit into Jack Howard, one of our neighborhood leaders who had attended the first meeting. “Jack,” he said, “I thought we were friends, and now I hear you have been circulating a petition behind my back. I’m really disappointed in you.”

“Our debut before the planning commission was a lesson in city politics. If no angry neighbors had been present that night, Barnes-Connally would have gotten the zoning change. Instead, the commissioners agreed to postpone the vote.”

From the guilt-trip gambit, Morton moved to a threaten-the-neighborhood-with-something-worse ploy. He maintained that Barnes-Connally Investments could build as many as 400 apartments on the ten acres zoned O. But since the developers wanted an especially nice project, they planned to buy the four-plus A-zoned acres, giving them room for “garden apartments” on all fifteen acres. They would build about 24 apartments per acre, fewer than the ordinance allowed, and they prepared to roll the O zoning back to B, Morton explained with an air of magnanimity. Since there was no benefit to us in changing O zoning to B—both permit 46 units per acre—and we would lose the A zoning, their offer was unacceptable.

I wish I could report that my team showed more class than Morton did, but this was our maiden negotiation. I have a vague but painful memory of angry wisecracks, detours into issues that turned out to be red herrings, and wistful proposals such as “Why can’t this be a park?” Somewhere in our rumbles and grumbles, however, was the germ of a coherent response. To wit, the city planning department had recommended BB zoning for this project, which allows no more than 24 units to the acre. After all, the land was close to an elementary school in an area that already had serious traffic problems; the city planners estimated that at B density the apartments would increase traffic by 14 per cent. We might accept 24 units an acre on the O land, but using our petition as a bargaining tool, we tried to hold Barnes-Connally to 12 units per acre (the maximum density allowed by A zoning) on the rest of the land.

Gary Davis’ angry retort was that 344 garden apartments were going up on fifteen acres whether we liked it or not. We told him that we were not about to give up A zoning so Barnes-Connally could build more apartments.

“But our bond funding is specifically for apartments,” Davis answered.

“What bonds?” I asked. He refused to say another word about them, implying that the financial details were none of our business and too complicated for us to understand anyway.

Then we offered some suggestions concerning the placement of driveways out of the complex. We made a pitch for saving as many live oaks as possible. We suggested that they build fewer efficiency apartments for single people and more two-bedroom units to accommodate families. We asked for a greenbelt and fencing around the property. We asked that the three-story apartment buildings be in low-lying areas and away from neighboring homes. Both sides opposed the extension of Havana Street. But the negotiations promptly bogged down when Davis asked us to withdraw our opposition in exchange for the improvements. When we balked, he threatened to proceed without a nod in our direction. I wanted to see if he was bluffing, so I grabbed my purse and prepared to leave. Morton jumped to his feet and said, “Well, perhaps Gary was being a bit hasty here.” I put my bag down, but the session soon ended in an uneasy standoff.

The next day, I started investigating the bonds that Davis had mentioned. It turned out that Barnes-Connally was taking advantage of a government program allowing local governments to lend their tax-exempt bond status to apartment builders. In theory, this tax break enables developers to build housing that the poor and the middle class can afford. It seemed to me, however, that the program primarily benefited Barnes-Connally. Travis County had authorized the firm to sell $10 million worth of tax-exempt housing bonds—enough to finance the entire project—at an interest rate of 9.98 per cent, lower than the prevailing commercial rate. In exchange for these goodies, rents had to be affordable to families earning less than $35,000 a year, and one fifth of the apartments had to be set aside for low-income tenants. (Under government guidelines, a family of four earning up to $18,000 a year qualified as poor. These folks would not get a reduction in rent, mind you, just an opportunity to rent at rates ranging from $355 to $525 a month.) The most interesting tidbit I picked up was that Barnes and Connally had already sold their bonds, which locked them into building at least 344 garden apartments, even though they didn’t have city approval to build them yet. No wonder Davis and Morton had become so agitated when we tried to discuss alternatives with them.

Most Austin neighborhood leaders believe that the city’s nine-member planning commission is tilted toward developers, but even the pro-developer members are committed to a rational planning process The planning commissioners I called were at first incredulous, then angry when I explained that Barnes-Connally had sold bonds before getting the proper zoning. It dawned on me that I wasn’t the only greenhorn in this skirmish; Barnes and Connally were neophytes too. Suddenly the match seemed to be a little more even.

I called Jack Morton to ask why he hadn’t explained the nature of the funding to us the night before. He explained that many groups opposed subsidized housing in their neighborhoods. I pointed out that we were not well-to-do and that we had no quarrel with low-cost housing. What we objected to was apartments being built on land that we thought should be used for houses or duplexes. Morton ignored my point but said that he liked my “style” and was sure that our negotiations would go better in the future.

At the next planning commission meeting, the newly christened Dawson Area Neighborhood Group (our motto: Give a DANG) turned out fifty strong, wearing orange Day-Glo name tags. I immediately spotted Barnes’ big blond Hereford head towering above the crowd. He was standing in the back of the city council chamber, next to Jack Morton and David Armbrust, the senior city lobbyist for Brown, Maroney. Barnes and I greeted each other in the best Texas political tradition—abrazos, effusive compliments and endearments—while Morton looked on uncomfortably. Barnes squeezed my hand and said he was proud of me for turning out such a whopping herd of neighbors. (He gave not a hint of our past differences. A master politician never stops trying to seduce his adversaries.) “Kaye,” he said, “can’t we go somewhere and talk this out—just you and me?” I was not about to go anywhere alone with Ben Barnes. He’s too persuasive. Besides, my neighbors might think I was selling them out.

I asked a few members of DANG to join us in the conference room behind the city council chambers. Soon the room was packed with people telling Barnes that more traffic on South Fifth would make it almost impossible for them to get out of their driveways safely. The PTA president said that a single, aged crossing guard guided grade-school children through the heavy traffic on South First and that the city refused to put a signal at the school because it wasn’t at a four-way intersection. Barnes, as personable as ever, listened carefully and responded with disarming candor. “I know how terrible traffic around schools can be,” he said. “In Brownwood, my hometown, a school guard was killed.” By the time our case was called, however, we had found no way to reconcile our differences.

After hearing us out, the planning commission put off its vote again, instructing the developers to meet with the neighborhood once more to search for a compromise. We were satisfied with the commission’s decision. It rarely rejects anything outright, but sometimes a project is postponed to death.

Our reception was significantly more cordial the next time we ascended to the conference room in the big gold bank building. Barnes was there, and before we could sit down, he asked, “Who wants coffee? I’ll send the girl—uh, Kaye, why don’t you and I get the coffee?” Off we went, alone at last, pouring coffees with and without sugar. Barnes explained to me that he had rushed to sell his tax-exempt bonds before the bond market changed. He said he earnestly hoped we could work something out, because he wanted to build a first-rate complex that would be a credit to the neighborhood.

Back at the conference table, I laid out our position. We had a valid petition on the 4.29 acres of A-zoned property, and we saw no reason to drop our opposition to the project unless Barnes-Connally built houses, duplexes, or townhouses at a density on that land. David Armbrust, scrupulously unemotional, presented a counteroffer: they would put duplexes on two acres, and we could choose where to place them. The units “lost” in that area would be built on the property zoned O, keeping the total at 344 apartments. We agreed to consider the proposal, but it wasn’t very attractive.

At the next DANG meeting, we voted to hold our ground. For two weeks yards went unmowed and children were ignored as we recontacted the planning commissioners, appeared on a radio talk show, and got our side of the story in the newspaper and on the TV news. We also introduced ourselves to city council members on the assumption that win or lose, the case would eventually go to the council. Since city elections were only a month away, no fewer than four campaigning council members visited our meetings.

Our last session before the planning commission was a rerun of the first, except that the neighborhood’s worst traffic scenario was confirmed by the analysis ordered by the commission. The study indicated that the northbound morning traffic from the apartments would use South Fifth and that congestion would reach a dangerous level in front of the elementary school. The only assistance the city could offer was a signal a few blocks south of the school, which, with luck, would provide some gaps in the traffic flow.

Armbrust told the commissioners that Barnes-Connally Investments had bent over backwards to accommodate the neighborhood. He argued that 344 units was a reasonable number to put on the site. We argued that the four-plus A acres would provide a buffer between the apartments and the rest of the neighborhood. We showed slides of rush-hour traffic around the school and tried to convince the commissioners that the only way to address the traffic problem was to reduce the density of the project, but Barnes had said he couldn’t do that because he had already sold his bonds.

It was almost midnight when the hearing ended. “This is one of the worst cases we’ve ever had,” groaned a weary commissioner. The commission debated an outright denial of Barnes’ zoning request, then reconsidered and asked us to try one more round of negotiations. Commissioner Larry Jackson, a former Black Panther and now a force to be reckoned with in East Austin, seemed to take pleasure in lecturing Barnes, who was slumped in a chair in the back of the chamber. “There are no votes on this planning commission for your project at your proposed level of density,” Jackson said. “I suggest you look for an alternate site.”

Barnes took Jackson’s advice. A few weeks later he called me to say that he was moving his apartments to another location and was giving up his option to buy the 4.29 acres. It has since been optioned by an Austin architect who says he doesn’t yet know what he will build. The neighborhood will have to do battle over it again if he asks for a zoning change.

Barnes went on to say that he had found a developer in San Antonio to buy the ten O acres and wanted to know if we would go along with 24 apartments to the acre on that section. Our eventual answer was yes. Our leverage had been the petition on the A land, which was essential to the Barnes-Connally project. Now our only recourse was to convince the city to block the special permits necessary for the new project. Since we had seen such permits approved routinely in the recent past, we decided it would be futile to object.

In retrospect, I wish we had gone through the motions of a fight. But we were simultaneously battling three other zoning bids and a plan to build a road through the floodplain, and we just didn’t have the energy to take on what seemed a lost cause. So we gave the new developer our tacit approval in exchange for every live oak he could possibly save and stringent runoff control to alleviate the serious flooding problems we had discovered nearby. The project will still penetrate all the way to South Fifth and cause traffic problems, but at least there will be 104 fewer units than Barnes intended to build, and no apartments will be built on the land closest to the school.

Barnes also has had some regrets concerning the apartment project. He recently said that he was politically naive in his dealings with DANG. He was quoted as saying, “I told them the truth. I should have told the neighborhood people I wanted thirty-two units to an acre and scaled it down to twenty-six. Then they could have won a great victory.” Still, he said, he had the last laugh: he made $350,000 on the sale of the property.

DANG has turned out to be about six consistently active people. I resent spending so much time in the neighborhood wars, but I don’t believe I have much choice. Even in the most neighborhood-oriented city in Texas, momentum is on the side of the developer. The good news is that DANG is now allied with other active groups in Austin. People who had never voted before were interested enough to do volunteer work in last year’s city elections. Best of all, we’ve actually become a neighborhood. We gossip on the phone, give each other rides to the grocery store, have potluck dinners, share Weed Eaters and pruning shears. We may be whittled down to a mere splinter of a neighborhood surrounded by offices, apartments, and traffic jams, but at least we’ll be in this thing together.

Ben Barnes should be proud.

Kaye Northcott lives in Austin and writes a regular neighborhood column for Third Coast magazine.

The Neighborhood Wars

Neighborhood groups still have to fight developers but may be about to turn on each other.

Texas’ neighborhood movement is barely a decade old, but it is growing along with our cities. In 1971 Austin had three registered groups. Today it leads the state with more than 175, and Dallas, with 156, is a close second. Groups usually form to address a particular problem—a zoning change, poor drainage, no streetlights. Some collapse once that problem is resolved, but those groups that persist emphasize one of three things: they supplement or take over some of the services of local governments, such as road repair and park maintenance; they regulate land use by protesting zoning and deed changes; or they become political watchdogs, fighting established policies and backing their own candidates for office.

Neighborhood organizations face similar issues across the state, but each city has its own problems. El Paso’s 20 struggling groups contend with the crime, drugs, gang warfare, and shortage of adequate housing that plague its barrios. Austin groups, such as the West Austin and Hyde Park neighborhood associations, are still waging turf wars, battling developers for the few remaining scraps of open land in the central city. San Antonio’s neighborhood movement emerged ten years ago with Communities Organized for Public Service, which has ballooned into a political conglomerate that covers 27 parishes. The most visible of the city’s 45 groups, like the one in King William and the 28-member San Antonio Coalition of Neighborhood Associations, concern themselves with the more genteel problems of preserving historical districts and blocking condominium developments in refurbished areas. Houston is unusual because instead of volunteer neighborhood groups, it has private, for-profit civic associations mandated by homeowners’ deeds. The 480 or so active associations function like little cities. Some hire their own policemen and build their own sidewalks; a few, such as River Oaks and Shadyside, have essentially walled themselves in like medieval towns. The civic associations exist mainly to enforce local deed restrictions, and they control everything from density to the kind of siding an owner puts on his house.

Two or three years ago neighborhood associations were popular mostly in the centers of cities, but lately more groups are springing up in unlikely places. Today Dallas’ neighborhood wars are being fought in wealthy, rapidly growing areas by people who have traditionally supported the local power structure. The Far North Dallas Homeowners Coalition has begun to combat traffic congestion and to oppose new businesses. The Williamsburg Homeowners Association has hired its own traffic consultant, as well as a lawyer to represent it in zoning battles. Dallas’ new, rich, noisy groups have not been entirely successful in stopping builders, but a recent tactic—creating supergroups, made up of thousands of members from smaller organizations—is scaring a few developers into hard bargaining. Some builders have even reconsidered prospective sites that are protected by vocal neighborhood associations.

This surge of activity should be good news to neighborhood groups around the state, but there are signs that all is not well. Some neighborhoods in suburbs and inner cities are beginning to turn on each other. Groups in the older areas of Central and North Dallas want the offices and apartments out of their cramped backyards. Residents in the outlying towns want to double-deck the Central Expressway and widen quiet center-city streets so they can get to work faster. Isn’t it only one short step to strong neighborhood organizations’ taking advantage of weaker ones? So what if the group on the next block is losing a battle over a new office building? All those people and buildings have to go somewhere. Why have an apartment complex in your midst if you can foist it off on somebody across town? Developers may soon be able to sit back and watch neighborhood groups fight over who gets stuck with what nobody wants.

Andrea Meditch

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- John Connally

- Ben Barnes

- Austin