When it comes to gun issues in Texas, proponents of gun safety—that is, gun control—have to take what they can get. So it was with Governor Greg Abbott’s School and Firearm Safety Action plan, announced May 30, in the wake of the deadly school shooting in Santa Fe. Abbott’s plan did include a few rare steps forward in the ongoing and mostly hopeless (for gun control advocates) debate. There was, for instance, a serious attempt to find funding for more school counselors who might actually help kids in trouble instead of simply presiding over administrative duties, a big step forward in mental health-averse Texas. There was interest in corporate threat assessment programs that instruct students and teachers in how to serve as distant early warning systems for potential trouble. (Yes, a sad commentary on our times.)

But overall, the governor’s plan to address school safety is profoundly regressive in ways that go far beyond the gun control debate. His call for more police and more military-style security raises crucial questions about what kind of places schools should be. Specifically, his plans for more armed guards, armed teachers, and armed staffers will erase a decade or so of progress in making schools more welcoming—and Texas’s kids better educated.

Maybe few Texans recall the zero-tolerance era, which started with the pre-Columbine U.S. Congress’s Gun-Free Schools Act in 1994 that required a one-year automatic expulsion for any kid who brought a gun to school. The Clinton administration encouraged schools receiving federal funding to adopt the tenets of gun-free schools, which became the basis of zero-tolerance policies in other areas. There were many unexpected consequences, especially punishments for minor infractions that could be looped in with the War on Drugs—as they could for entering a classroom without permission, or roughhousing on a school bus, kids could be expelled for bringing asthma inhalers and Sudafed to school. It probably wasn’t a coincidence that the zero-tolerance era coincided with the tough-on-crime era of the Bush and Clinton administrations that led to exponential increases in prison sentences for minor offenses, particularly for men of color. The so-called school-to-prison pipeline was born.

Over the ensuing years, groups like Texas Appleseed worked overtime to issue reports and lobby the legislature to reduce school suspensions (some of which started in kindergarten) and dire punishments for, say, talking back to teachers. Their reports also showed that so-called Juvenile Justice Alternative Education Programs were basically low-cost jails for kids and profit centers for private companies that did nothing but put good kids in with bad and offered no educational value to either. Studies also showed that putting more police in schools had a detrimental effect on learning, especially among poor and minority kids who were now the target of police abuse both on the street and in schools. It wasn’t surprising that dropout rates increased.

Over time, it became clear that zero tolerance just didn’t work. Newer programs like Restorative Justice, which allow kids to have their say and teach them to take responsibility for their actions, have won the support of liberal and conservative groups largely because they do. Even though they can be more labor intensive, they have been shown in numerous studies to keep kids in school and violence down. “What we have shown in our research and what we know experts have documented across the U.S. is that an increase in law enforcement doesn’t lead to a safer school and often results in real harm, particularly for students of color and students with disabilities,” explained Deborah Fowler, executive director of Texas Appleseed.

Abbott’s report, then, has the musty whiff of a darker time, despite protestations that more protections—offering gun training to nearly everyone who isn’t a student—are needed to keep kids safe. This despite an FBI report, among others, that shows no statistical evidence that putting more armed people in schools reduces school violence.

Then too, the governor has called for more collaboration between schools and local law enforcement, along with the hiring of retired police, sheriffs, and constables to work in schools. The last few years have been replete with reports of abuse of students by school police in Texas, most often involving the treatment of minority kids—remember the 14-year-old Sudanese student arrested in his Irving, Texas, school for having a “bomb” that turned out to be an alarm clock?—and special-ed kids, whose behaviors can be disruptive if not defused properly. The governor focuses on active shooter training in his plan, but that doesn’t reflect the day-to-day reality of police officers in schools, whose short training sessions—forty to eighty hours—have little to do with understanding the psychology of children or teenagers, or, for that matter, the increasing racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity of modern Texas.

Most likely, if the governor’s plan is enacted as is, it will send more kids to disciplinary programs and, if the past is any indication, make school even less enticing than it already is—test prep, anyone?—and, in turn, increase dropout rates. Texas Appleseed has already begun to receive more reports of kids funneled into juvenile courts for minor offenses. Examples include a dyslexic ten-year-old who was suspended for three days for a “terroristic threat” after an argument with another child over a video game. Then there was the sixth grader suspended for pretending to shoot zombies in the school hallway—he was charged with exhibition of a firearm, even though he didn’t have one. Another involved a 12-year-old biracial special-ed student with facial deformities and no criminal history who was bullied after a toilet accident. He threatened his persecutor in return, and then was suspended for a day, and, when he returned to school, was publicly arrested by an HISD school police officer and then sent for a night to juvenile detention. The Harris County district attorney is charging him with a felony terroristic threat. And so on.

There’s no doubt that school shootings are frightening for all, but it’s worth noting that a February 2018 study released by Northeastern University found that, overall, schools are still the safest places for kids. Before the school doors are bolted and the teachers armed and deputized, it’s worth asking whether a return to zero tolerance and even more militarized schools is going to do more harm than good.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Crime

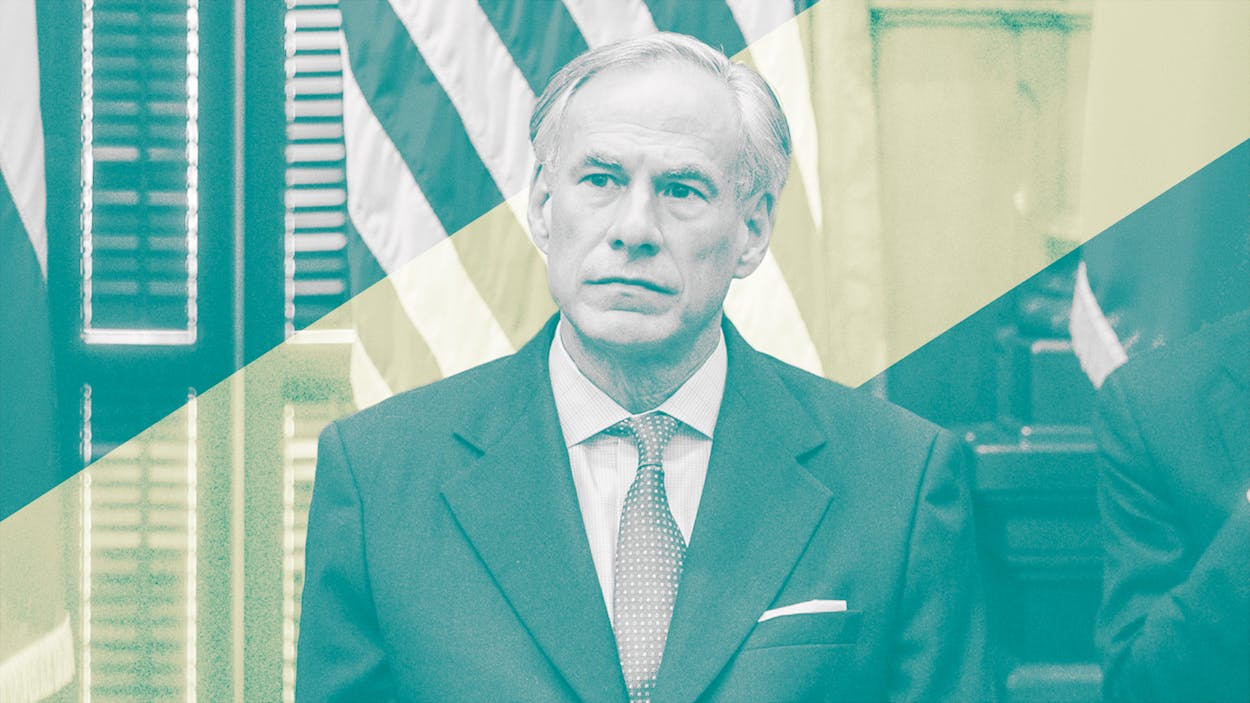

- Greg Abbott