This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

You are the most tolerant and forgiving constituency in the world.” With those truest of words, Charlie Wilson, for twelve terms the congressman from the heart of East Texas, announced his escape from politics and public scrutiny. At 62, standing atop the steps of the federal courthouse in Lufkin, he looked at least a decade younger, a lean and lanky testament to the preservative powers of a lifetime of whiskey, women, and God knows what else. Seldom has his name appeared in print without the word “flamboyant” attached to it. He has been accused of using cocaine, arrested for driving while intoxicated, and investigated for everything from misusing campaign funds to taking his girlfriend(s) along on international trips. The only sin that he hasn’t committed is losing an election. “I know that at times I’ve been a reckless and rowdy public servant,” he confessed to the hundred or so people who turned out for the formal announcement on an overcast October morning. The crowd was on the small side, but then the retirement of a congressman is not big news in American politics, especially in a year when so many Democrats are getting out. A member of Congress is 1 person among 435. Except for his escapades, Wilson had never broken loose from the pack: He had never held a committee chairmanship, never passed a major piece of legislation, never risen in the Democratic party’s ranks of leadership. His exit rated just a squib in the New York Times and hardly more in most Texas papers. At a time when character is the supreme issue in American politics, there seemed little reason to regret the departure of someone who swam so relentlessly against the moral current.

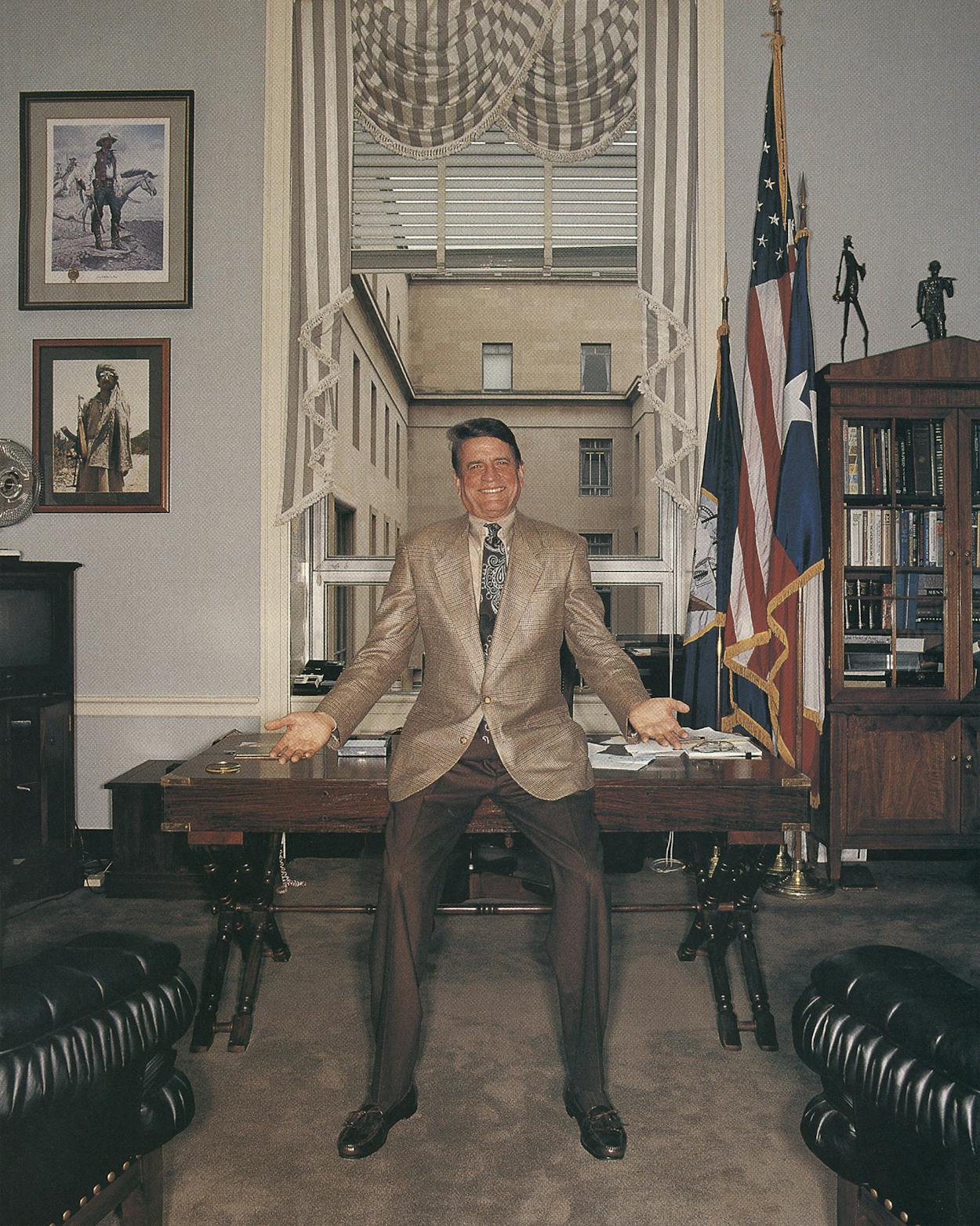

But there is more to politics than good behavior—and there is more to Charlie Wilson than a career of indiscretions. He entered politics in 1960, running for state representative in a year when John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson headed his party’s ticket. He leaves as one of the last practitioners in Congress of LBJ-style politics and the last Texas representative of a political tradition that has been all but extinguished: a pragmatic liberalism that championed both guns and butter and took up for business, especially Texas business. Like Johnson, he excels at the mysterious arts of politics you never read about in the papers or see on television. He is a superb strategist, a shrewd judge of people and of the many moods of the House, an astute vote-estimator, and the best inside operator Texas has sent to Washington in the past quarter century. He is a generalist in a body of specialists, a moderate in a body of ideologues, and such a good one-on-one politician in a body of C-SPAN speechifiers that the Almanac of American Politics has noted that “he does retail better than Wal-Mart.” His array of political skills enabled him to overcome a reputation that might otherwise have made him a pariah and gave him the opportunity to change the world. More than any other member of Congress, he helped bring about the collapse of the Soviet Union by funding the mujahedeen resistance to Soviet troops in Afghanistan.

I must admit to being a less than neutral observer, having a relationship with Wilson that goes back to the late sixties, when he was a state senator and I was a Senate aide. He cut a grand figure even then, flaunting his yellow shirts and green sport coats and miniskirted aides before a staid Senate. His reputed approach to hiring staff is still quoted around the Capitol: “You can teach ’em to type but you can’t teach ’em to grow tits.” One of his many escapes from the clutches of the law came when an excuse from his doctor miraculously metamorphosed a DWI charge into a case of driving under the influence of prescription drugs.

In debate he would stand so ramrod straight that he gave the illusion of tilting backward, as if he were still in his student days at the Naval Academy. He was reputed to be a liberal at a time when the appellation was something to be proud of, but neither the conservatives nor the liberals knew exactly what he was. He voted with independent oilmen and against the telephone company, and the difference was that oilmen were good sumbitches to be around and phone company types weren’t, which was Wilson’s instinctive way of differentiating between Texas entrepreneurs and out-of-state monopoly corporations. Sometimes he did things I found unfathomable, such as casting the decisive vote against a natural-gas tax increase that the liberals thought he supported. His wife, Jerry—yes, Wilson was married, for seventeen years—shouted from the balcony, “You fink!” But he had promised the oilmen that he would vote against a particular form of the tax, which happened to be the one that came up for a vote, and one thing that anybody would tell you about Charlie Wilson was that he never broke his word. His political behavior with his peers was impeccable.

Later, after he went to Congress and I became a journalist, he would be the first person I interviewed whenever a story took me to Washington. He could size up a political situation quicker, more accurately, and with more candor than anyone else in the delegation. He knew that the Democratic leadership’s effort to defeat Ronald Reagan’s budget in 1981 was doomed even as majority leader Jim Wright was telling me why they would win and how they would punish party members who strayed from the fold. In 1988, when Wright was Speaker and Republicans were attacking him for intervening with federal regulators during the savings-and-loan scandal, Wilson knew that Wright could not survive, long before that was the conventional wisdom. “Wright made the Republicans hate him,” he told me then, shaking his head sadly. To Wilson, enmity was the deadliest sin. He never got mad for keeps, nor did he let anyone stay mad at him—including former girlfriends. His own weaknesses kept him from judging others too harshly, and his unapologetic acknowledgement of frailty kept others from being judgmental in return. When I accused him during one long-ago interview of exaggerating his role as mediator during a battle over natural gas deregulation, he looked hurt. “Look,” he said, “I may tell you how great I am, but I don’t expect you to believe every word. I’m not like Gammage [Bob Gammage, then a congressman from Houston]. He expects you to believe it and gets offended if you don’t.” It was typical of Wilson that during his retirement announcement, he greeted the reporters by saying, “I’ll even thank the pesky news folks, who have aggravated me often, but seldom unfairly.”

And so I have come to believe that Charlie Wilson passes the character test. He is true to himself, and I have never known him to be false with the public. You would never turn on a TV newscast and see him engage in the popular sports of manipulating statistics, demonizing the opposition, and exhibiting total self-assurance that he has all the answers to the nation’s problems. The kind of finger-in-the-wind politician who doesn’t pass the character test was described by the political commentator Walter Lippmann more than forty years ago: “With exceptions so rare that they are regarded as miracles and freaks of nature, successful democratic politicians are insecure and intimidated men,” Lippmann wrote in a pessimistic tract called The Public Philosophy. “They advance politically only as they placate, appease, bribe, seduce, bamboozle, or otherwise manage to manipulate the demanding and threatening elements in their constituencies. The decisive consideration is not whether a proposition is good but whether it is popular—not whether it will work well and prove itself but whether the active talking constituents like it immediately.” These are the political vices of the modern age, but they are not Charlie Wilson’s vices.

It would be nice if our politicians were paragons of personal virtue. But it is wrong to demand it of them. Such expectations can never be met, and disappointment and disillusionment inevitably follow. Not by coincidence has our age, which is so insistent upon purity in personal behavior, also produced an insistence upon purity in political doctrine. Those expectations likewise can never be met, and more disappointment and more disillusionment with politics will be the result.

Still, one cannot flout the rules without paying a price, and Wilson has paid dearly. At the start of his career he was ambitious, not content to be just a good-time Charlie. In his second term in Congress, he out-lobbied a fellow Texan, Richard White of El Paso, for a seat on the powerful Appropriations Committee, even though White’s seniority gave him the backing of the Texas delegation. That ordinarily should have settled matters in his favor, but Wilson went straight to the members of the Democratic Steering and Policy Committee, who had the final say. He won them over with the argument that he was more liberal than White, who in any case was no match for him in face-to-face politics. On Appropriations he became the contact for anyone in Texas who depended on federal money, especially defense contractors in the Dallas–Fort Worth area. Soon Wilson had his eye on a U.S. Senate seat. Lloyd Bentsen was running for president in 1976, and if he ended up on the national ticket and won, Wilson planned to run for his seat. He might have made it too. He had the uncanny ability to make friends with implacable foes—oil and labor, the National Rifle Association and animal-rights supporters—without being two-faced. He was a liberal who could raise money from business: the East Texas lumber industry (he was so close to Arthur Temple that in Austin he had been known as Timber Charlie), independent oilmen (he convinced Northern liberals that independents were little guys who deserved to keep the tax breaks that the big oil companies were losing), and the defense contractors he befriended on the Appropriations Committee. Or perhaps he was a moderate conservative with ties to liberal groups like Jews (he was a staunch supporter of Israel) and labor. But Bentsen’s campaign cratered, and Wilson turned his eye toward Republican John Tower’s seat in 1984. “He’s the luckiest S.O.B. in Texas,” Wilson told me once. “Every time he’s run, the Democratic party has been split. Some day his luck is going to run out.” It did, of course, but not before Tower had left the Senate for an ill-starred sojourn as Secretary of Defense and Phil Gramm had taken his place.

By that time Wilson’s luck had run out too. There had been too many public escapades: a weekend at sea on an aircraft carrier with a girlfriend (“She improved the morale of the sailors,” Wilson told reporters), trips to Nicaragua as the guest of the dictator Anastasio Somoza, and the devastating charge that he had used cocaine. He was exonerated because his accuser, a prison inmate who claimed to be an eyewitness, wasn’t credible. This is the only one of his scrapes that Wilson is somber about. “I was in a hot tub with a couple of models from New York,” he told me recently when I asked about the incident, “and someone stuck a finger under my nose. Back then, every model in town had cocaine in her purse.” In Wilson’s office, aides began giving nicknames to his string of girlfriends: Snowflake, Bombshell, Tornado, Sweetums, Cupcake, Firecracker. Once he fell for a Russian woman and sponsored her way to America, despite friends’ warnings that she might be a KGB agent. When she arrived, Wilson gave her a credit card and she went on a buying spree. A Washington Post reporter saw them together in a restaurant and approached Wilson to ask if he was sure she wasn’t a Russian agent. “The only secrets she’s going to take home,” Wilson answered, “are Victoria’s.”

As his chance for statewide office faded into the past, the escapades seemed to grow more frequent—and Wilson less repentant. He collided with a car on a Potomac bridge in 1983 but didn’t stop; he said later that he thought he’d hit a guardrail. In 1992 he had 81 overdrafts on the now-defunct House bank—“If my constituents didn’t forgive sloppiness and a certain amount of eccentricity, I wouldn’t be here in the first place,” said Wilson—and just this year he paid a $90,000 fine to the Federal Election Commission for misreporting loans to his campaign. His most infamous scrape came in 1989, when he used the federal budget to get even with an offending agency. Wilson had taken a former Miss USA on a trip to Pakistan. A U.S. military plane took them to one destination, but when Wilson and his girlfriend tried to return to their starting point, a Defense Intelligence Agency colonel invoked an obscure rule and barred her way. “I just went crazy,” Wilson told me in Lufkin. “I was embarrassed. I said I would pay for her—I had a check ready for commercial airfare plus a dollar, which was standard practice at the time. I had to call President Zia, and he sent an airplane to bring us back. Evidently the president of Pakistan understood the congressional appropriations process better than the Defense Intelligence Agency.” No doubt the DIA understands it better now. The agency lost two airplanes and its exemption from Gramm-Rudman budget cuts. “One reason I hate to leave Congress,” Wilson told me, “is that the DIA might get their airplanes back.”

The cause of the mujahedeen rejuvenated Wilson, who had not been happy with the increasingly leftward drift of the House Democratic leadership following Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980. (“The right never did care about the working man,” Wilson lamented to me during our recent interview, “and now the left doesn’t care either.”) He read that “the Muj,” as he calls them, were fighting with rocks and knives during the early days of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. “I decided on the spot that if these people were brave enough to fight, then I was going to help them,” he recalled. “They wanted to kill Russians, and I wanted to kill Russians, as painfully as possible.” No one else on the Appropriations Committee seemed very interested, but Wilson had an advantage: “I didn’t have any military bases or contracts in my district. Everybody else did. They were worried about their planes and tanks. I voted for anything—anything—if they would vote for the Muj.” At first Wilson arranged for medical aid, then military. He doubled the amount of money the CIA requested. He supplied the Muj with Stinger missiles to shoot down helicopters. He even stopped drinking for a year and a half as the tide began to turn against the Soviets.

In 1988, as the mujahedeen neared victory, CBS’ 60 Minutes aired an episode called “Charlie Did It.” The title was lifted from an on-camera interview with President Zia of Pakistan, who gave Wilson total credit for bringing down the Soviets. (Later, CIA director James Woolsey would credit Wilson and Poland’s Lech Walesa as the two individuals who did the most to cause the Soviet collapse.) To see the show now is to sigh for what might have been. Early in the episode Wilson rides into a mujahedeen camp on a white horse, looking so natty in an Afghan field vest and hat that he might have been posing for a Banana Republic ad. No politician has ever looked better. “I love sticking it to the Russians,” he tells Harry Reasoner. “They’re going to lose, and I love it.”

But that was long ago and Wilson has found no great cause since. Without a global priority, he turned in the nineties to getting money for his district. Lo and behold, the defense contractors he had been helping all those years suddenly discovered a need to build plants in East Texas or to hire subcontractors there. He dipped into urban mass transit funds to get a bus system that is neither urban nor mass by telling liberals that the buses would take poor people to hospitals and telling conservatives that they would bring students to community colleges. These things matter a lot if you happen to live in East Texas, but they aren’t enough to engage Charlie Wilson’s attention forever, especially when the federal pot is going to contain fewer dollars—and fewer still for Democrats. I wasn’t surprised when word leaked out that Wilson was planning to retire.

I went to Lufkin to ask Wilson if he had any regrets, particularly about the issue of character that had always dogged him. I already knew that he responded to political attacks on his character with defiance; he never ran from his reputation. If an opponent called him a womanizer, he’d bring his girlfriend of the moment to the district to campaign. Wilson swears that the Lions and Rotary got their biggest crowds when he came to give a speech; they came out just to see what the companion du jour looked like. In 1990, when he faced a tough race for reelection, he told me, “If you live a clean life and have one bad escapade, it’ll kill you politically. People think you’re a phony. But when your whole life is escapades, they forgive you.”

We met at a steakhouse south of town the night before the speech. He was joined by aides, old friends, and an attractive woman with wise eyes whom he introduced as “my Lufkin girlfriend.” It was a night for telling old stories, and when Wilson launched into a tale about a trip he had taken to Mexico to study Spanish, the girlfriend broke in. “Charlie,” she said, “he’s not going to believe that. You’ve never been to Mexico by yourself in your life.” Wilson munched away on a huge ribeye and a baked potato amply lubricated with butter, a diet that has done no noticeable damage to his physique. Eventually people began to drift away and we had a chance to talk.

“What are you going to do?” I asked. “Are you going to lobby?”

“In Washington, we call it consulting,” he said with mock gravity. “There’s a lot of natural gas in Turkistan, and one way to get it out might be through Afghanistan and Pakistan. I know that part of the world. But for now I’ll probably serve out the rest of my term.”

I asked about regrets. Did his reputation keep him from becoming a leader in the House? “I never wanted to be a leader in the House,” Wilson said. “I’m not a caucus politician.” His face took on an uncomprehending look, as if to say: Are you seriously asking me whether I would rather spend my life being a deputy whip or being with some of the most beautiful women in the world?

What about the Senate? “I don’t think I would have made it. A liberal couldn’t raise the money.” A liberal? Charlie Wilson never was considered a liberal by the liberals. But neither was he regarded as a conservative by the conservatives. For a moment a door to his psyche was open, and I could see the effect of being someone who spent his career as the man in the middle, the supreme dealmaker lost in an age of polarization. He was always liked by everyone, but he was never invited to join a club.

The next day, after Wilson finished his speech, two gospel singers sang in harmony:

May the work that I’ve done speak for me.

May the service that I give speak for me.

When I’ve done the best I can and my friends don’t understand,

May the work that I’ve done speak for me.

As the crowd dispersed, a Wilson staffer came over to me with a wink. “You know there’s another verse, don’t you?” he said. “It begins, ‘May the deeds that I’ve done speak for me.’ But Charlie decided we’d better cut it.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Lufkin