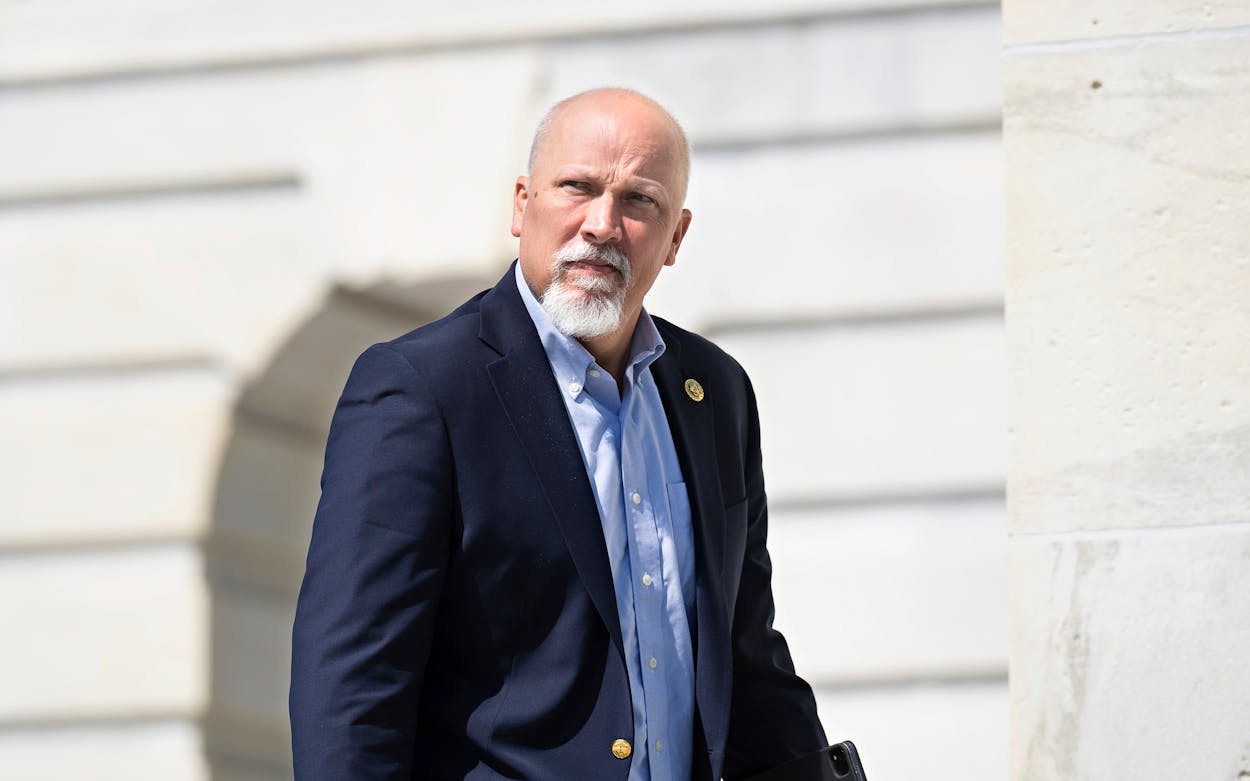

Congressman Chip Roy was in a mood. It was 2:22 on Wednesday morning. The U.S. House of Representatives had just adjourned after another day of Republican infighting over how, or whether, to keep the government open. An autumn chill had set in on Capitol Hill. “Why is everybody running around acting like their entire life comes from that shithole?” asked the Austin congressman, pointing a finger at the Capitol building. “It drives me out of my frickin’ mind.”

I’d asked Roy if Texas would be prepared if a natural disaster—such as, say, a hurricane—hit during a government shutdown. “I could do with a very non-damaging, non-harmful hurricane; come and sit over the Hill Country and give me some rains. We’re in a drought.”

I asked him to try again. What would he say if Texas really did get hit with a natural disaster during the shutdown? “Deal with it! We’re Texas. We’re the biggest g—damn economy in the world,” he said, with considerable hyperbole. (The Texas economy ranks eighth.) “Everybody’s running around going, ‘Oh my God! What if some terrible thing happens?’ I don’t know. Figure it out. My great-great grandfather didn’t run around when he was a Texas Ranger in 1870 going, ‘Oh my God, what will the federal government please do for me?’ ”

Roy, who was born in Bethesda, Maryland, has long held that Texas could get by without the federal government, even though each year the state takes $28 billion more from Washington than it pays in federal taxes. Roy’s position has made him instrumental in government shutdowns. A decade ago, he was Senator Ted Cruz’s chief of staff and helped Cruz instigate a shutdown in an attempt to defund the Affordable Care Act. That effort failed and was widely regarded, including by some leading Republicans, as a disaster for the party. For sixteen days, unemployment insurance claims surged as families scrambled against the uncertainty. Overall, 850,000 government workers were furloughed, losing the equivalent of 6.6 million work days. Depending on when they were polled, as many as 53 percent of Americans blamed Republicans in Congress, while smaller percentages blamed Democrats or the president or all the above. While the shutdown didn’t hurt Cruz’s standing among Texas Republicans, his reputation among GOP colleagues in Congress never recovered. “It wasn’t about the shutdown. It wasn’t about the Affordable Care Act. It was about launching Ted Cruz,” said Tom Coburn, a Republican senator from Oklahoma who died in 2020.

Three years later, Cruz launched his presidential primary campaign, but dropped out after a devastating loss to Donald Trump in the Indiana primary. Two years after that, the Texas senator won reelection against Beto O’Rourke by just three percentage points, the narrowest margin of victory for a Republican in a statewide race since Rick Perry was elected lieutenant governor in 1998. Cruz has been conspicuously silent on the shutdown talks this time around.

That’s not the case for Roy, who was elected to Congress in 2018, representing a district redrawn to favor Republicans. Its eastern edge runs from north San Antonio to South Austin, then extends more than one hundred miles north and west into five largely rural, red-voting counties. In this year’s funding fight, Roy is among a handful of far-right House GOP members pushing for drastic but generally nonspecific spending cuts and legislation for armed measures to block illegal immigration—measures that stand no chance of passing the Democrat-controlled Senate.

As the disarray in the House Republican conference has become a punch line in the national political debate, Roy has led floor debates and introduced amendments late into the night and the wee morning hours. On Thursday, Roy huddled with Louisiana representative Garret Graves, a close ally to House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, with whom the Texas Republican has frequently found himself at odds in this Congress.

One area of alignment between Roy and the House GOP leadership is on the Texas Republican’s much-discussed immigration bill. Known as House Resolution 2, Roy’s bill would alter migrant rights to asylum and other basic humanitarian assistance by redefining which classes of immigrant would qualify for protections and expediting removals. McCarthy now demands the Senate include the provisions of Roy’s bill in what’s known as a continuing resolution to fund the government for thirty days, a negotiating point Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer has repeatedly called a non-starter. Even minority leader Mitch McConnell opposes the deal, arguing in a floor speech on Wednesday that government shutdowns are no way to negotiate policy and, in political terms, tend to be “a loser for Republicans.”

Meanwhile, millions of federal workers, including military personnel, will stop getting paid unless Congress acts to fund the government. A federal shutdown would affect the lives of hundreds of thousands of Texans. The federal government employs roughly 114,200 active-duty members of the military and 123,000 civilian workers in the state. Some agencies have cash reserves to hold them over for a time, but those that don’t will be unable to pay their workers once the federal government shuts down. Employees deemed “essential,” such as certain law enforcement and military personnel, will be required to work without pay for the duration of the shutdown, with back pay likely (but by no means guaranteed) when the shutdown concludes.

Despite ongoing negotiations among House Republicans (Democratic leader Hakeem Jeffries told Texas Monthly on Wednesday that McCarthy was not speaking to him) about a thirty-day spending bill to keep the government open, representatives and their aides say that a deal is unlikely. To Roy, a government shutdown is a reasonable price to pay to force at least temporary federal spending cuts, and to allow Republicans to emphasize their opposition to illegal immigration—a position many swing voters now share. Roy’s message to the active-duty military personnel in his district who are concerned about the shutdown? “They’re not fighting for a bankrupt country or a country that has no borders,” he said early on Thursday morning after another grueling political day of floor debates that went past 1 a.m. “They got their paychecks on September twenty-ninth and we’ll see what happens between now and this weekend.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ted Cruz

- Chip Roy