Kevin Emr was bouncing from company to company as a product development engineer in Dallas when he got a call about a dream job he didn’t know he wanted. He had been a car enthusiast for as long as he could remember—the kind of boy who could identify any vehicle by the shape of its taillights, the kind of teenager who got his first job in a mechanic’s shop. The Houston native chose his college, the University of Texas at Arlington, because it offered a motorsports program, and imagined a career with a professional racing team. But the 2008 financial crisis sent motorsports into a slump right as he was graduating. He’d settled for building and racing sports cars on weekends.

Then came the call. It was from Bill Schofield, an executive with whom Emr (pronounced “Emmer”) had worked about ten years earlier, at a company that sold large-scale circuit breakers for power plants and other industrial customers. They hadn’t been particularly close—Schofield was twenty years older and the president of the company—but the two had bonded over their love of cars. Schofield explained to Emr that he had made a small fortune when the circuit breaker company was sold, and he had decided to retire early, at 57.

At an auction, Schofield had bought his teenage fantasy, a 1968 Chevrolet Camaro RS, one of the original muscle cars. It was Grotto Blue with a pristine white convertible top and a clean interior—not quite museum ready but close. Then he’d bought another classic Camaro, a white ’67 SS hardtop. There was only one problem: the cars were a nightmare to drive and maintain. They leaked coolant and transmission fluid and needed constant tune-ups. He kept a tow truck on speed dial. Schofield’s regular ride, a Porsche Taycan EV—and before that a Tesla Model S—accelerated faster, handled better, and didn’t break down.

“I’ve got a crazy idea,” he told Emr.

Less than two years after that fateful call, Emr sits in a small office off the showroom floor of a monster-truck-tuning shop on the Interstate 35E access road in Denton. The forty-year-old’s new job: president of E-Muscle Cars, a company he and Schofield launched to convert classic cars into electric vehicles. EVs were hardly Emr’s automotive specialty when Schofield called, but high-performance sports cars were. “I’m a gearhead, a hot-rodder,” he says, while his baby-blue polo shirt and tendency to lapse into long technical explanations betray his inner computer geek.

Schofield had bought a few pieces of commercial real estate around North Texas with his windfall from the sale of the circuit breaker company—mostly gas stations and car washes that could generate steady cash flow. One was this showroom. He planned to store his new hot rods in the garage out back and use the office to do some business consulting. That plan got a little more complicated when he decided to let the existing tenant, Havok Truck Accessories, stick around, and more complicated still when he invited Emr to join him.

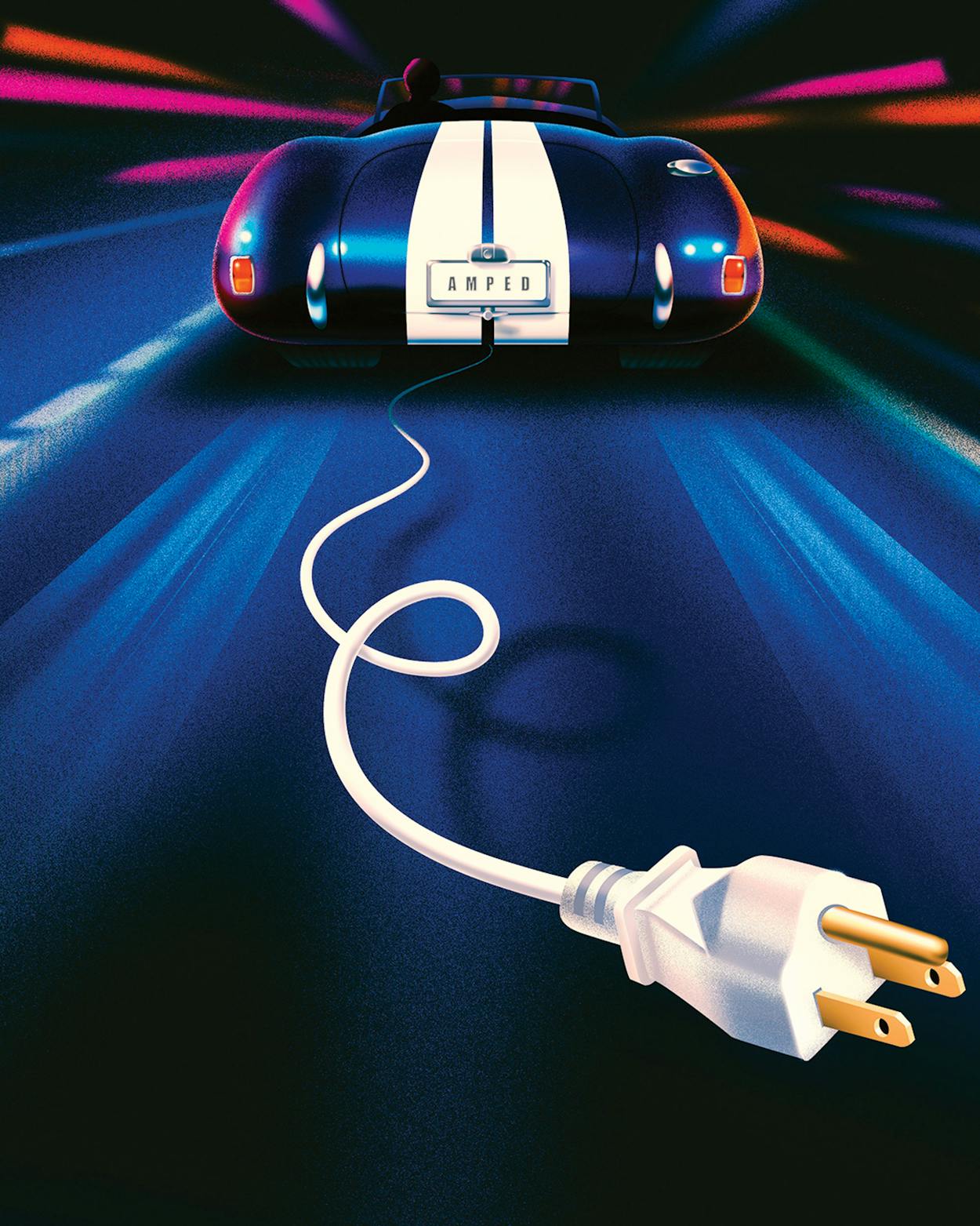

Schofield, who has the clenched-jaw energy and bravado of an NFL coach, now had a space where myriad motor trends converge. Posters for an annual spring break truck show the Havok guys put on called Rednecks With Paychecks adorn the showroom walls. In Emr’s office, his racing schedule hangs near a large portrait of the German-born Formula One legend Michael Schumacher. In the garage, an array of MAGA flags hangs over an area where two young mechanics peer into the back end of a 1965 royal blue Shelby Cobra with white Le Mans stripes. Between the rear wheels of this celebrated artifact of the golden age of internal combustion sits a cylindrical repurposed Tesla engine.

At first Schofield’s idea for the EV business was little more than a fun excuse to convert his collector cars and maybe do the same for a few of his friends. But in the fall of 2022, he and Emr visited the SEMA auto show in Las Vegas, the predominant exhibition for aftermarket car parts and hot rods, named for the Specialty Equipment Market Association. There they were motivated to pursue a much bigger opportunity. If they combined their professional skills—Emr’s electrical- and mechanical-engineering background and Schofield’s business acumen—they could create 3D computer–aided design models, build a reliable supply chain, and perfect the process of converting a handful of popular classic cars, ones with a proven market among collectors.

Today, in a corner of the showroom just outside the two men’s adjacent offices, sits Schofield’s ’68 Camaro, its hood open and most of the original parts replaced, awaiting its batteries. In the engine bay of an EV, there are no belts, and the various gears and other moving parts are contained within the compact electrical motor—but the batteries occupy even more space than those modifications free up. In the Camaro, about two thirds of the battery array will sit in the rear and another third up front.

Once it hits the road, Emr says, this car will have double the horsepower and double the torque of its original configuration as a gas burner. That means it will accelerate from 0 to 60 in about three seconds, easily twice as quickly as it used to, and will have a top speed of about 150 miles per hour. Most of E-Muscle Cars’ vehicles will offer about 150 miles of range before they require recharging, but Emr hopes this one will top 250—enough to drive nonstop from Denton to Austin.

If E-Muscle Cars were to sell the Camaro, it would go for at least $200,000. It’s an eye-popping number, but the car itself cost Schofield nearly $50,000 at auction. The company spent another $120,000 for modifications, including the battery array and motor, which cost about $40,000 each. The electronics and other upgrades made up the balance.

Those other upgrades? Not just a charging port and new gauges built to match the originals (a kilowatt meter where the tachometer was, a battery-charge display where the fuel was) but also new steering, brakes, suspension, and cooling systems. “Old cars have loose and inaccurate steering and sixty-year-old components,” Emr explains. The batteries add weight that can change the suspension needs. If you were to hammer the accelerator in a converted muscle car without any of those systems being replaced—well, “we would highly advise against that,” he says. You’d end up in a ditch.

The future of wheeled transportation this is not—but that’s not the motivation anyway. “It’s taking internal-combustion muscle and just swapping for electric muscle,” Emr says. “It actually hauls more ass.”

Schofield and Emr were hardly the first to start building EV conversions—it’s been done for decades, for much of that time by garage tinkerers frustrated that they couldn’t get an EV any other way. “Back in the day, these dudes would get a forklift motor and a bunch of batteries and make a mad-scientist experiment in their Geo Metro,” says Marc Davis, the founder of Moment Motor Company, an EV conversion shop in Austin. “They were just trying to get it down the road.”

Then along came Tesla and a few early electric models from established car companies, such as the Nissan Leaf and Chevy Volt, which quickly erased the need for homemade EVs. This also ushered in a new generation of battery tech, and by the mid to late 2010s, the focus in the conversion community turned to power and speed. If you wanted a get-around-town car, there were good, reliable ones to buy the traditional way. If you wanted something that might turn heads, there was suddenly a whole new world of automotive performance to explore.

Davis, fifty years old with white hair and piercing blue eyes, is a computer science graduate from Cornell University who started his career as an IBM software developer and then spent more than twenty years at Austin tech start-ups before he founded Moment, in 2017. In the back corner of an industrial office park in South Austin, he presides over a team of ten that works primarily on classic European sports cars.

Whereas E-Muscle Cars buys and sells its own vehicles, Moment operates as a custom shop for owners who want their cars modified. Like E-Muscle Cars, Davis’s company aims to professionalize the process enough to unlock time and money savings, especially on the more popular models that come through again and again. In its six years, Moment has completed 37 conversions, Davis says, and in the process identified several models that are becoming house specialties—Porsche 911s and Speedster replicas, Mercedes SL convertibles, and BMW 2002s.

There’s at least one other EV conversion company in Texas—Flash-Drive Motors, in tiny Coupland, about thirty miles northeast of Austin—but overall the market remains in its infancy. Luis Morales, the director of new vehicle technology at SEMA, first decided to showcase EV conversions at the association’s annual show in 2019. There were four cars that year but twice as many in 2021. Then in 2022—the year Emr and Schofield showed up—the EV exhibit covered 21,000 square feet of floor space and featured about twenty converted vehicles, as well as training programs, tools, and equipment.

Nobody’s sure how many companies have sprung up in the conversion market nationwide, but Morales’s best guess is in the dozens—“definitely less than one hundred,” he says. Many of those are little more than a couple of hot rod mechanics trying their hand at something new, turning out one-off novelty projects. Morales calls these fabricators, because the work is largely manual, more gearhead art than science. E-Muscle Cars and Moment Motor are what he calls integrators, shops that build repeatable, precision-engineered systems. (The biggest brands in the space, such as Southern California–based EV West, have evolved to supply parts and even whole conversion kits to other shops.)

As all of those types of shops proliferated, the wider market for collector cars boomed, with record numbers selling at U.S. auctions during the peak COVID-19 years, according to the Hagerty insurance company, which specializes in collector vehicles. (Sales surged in 2021, peaked in June 2022, and have since receded closer to pre-COVID levels.) A rise in gas prices during the same period helped drive up sales of EVs. And meanwhile people from all over moved to Texas.

Those factors demonstrate why Emr and Schofield believe their business is launching at just the right time and place. “We have more roads, more money, and more people in Texas,” Emr says. “And it’s a car culture here. There are racetracks and drag strips here. So it makes sense why people adopt fast, new cars.”

One phrase that neither he nor Schofield utters is “climate change.” The main reasons to be drawn to EV muscle cars, they maintain, are for their performance, ease of maintenance (relative to gas-powered classics), and “cool” factor. “The side effect is less emissions,” says Emr.

Moment’s Davis puts it another way, pointing out that old cars simply weren’t built to accommodate big, heavy batteries or designed down to the millimeter to maximize aerodynamics and drivetrain efficiency. As a result, they have a shorter battery life and require more energy per mile than a new EV—and cost several times as much.

“Cars are emotional things,” he says. “A client will bring in their dead father’s car, and it’s deeply meaningful to them, but they can’t bear to drive a combustion-engine vehicle. Does it make sense? No. It costs a gazillion dollars, and you’ll never make it back on gas savings or anything like that. But if the car is important to you, this is the way to do it.” He pauses. “Of course, some people bring us a car and just want us to make it flaming hot.”

Back in Denton, a greatest-hits list of dream machines sits in the E-Muscle Cars garage and in a parking area just behind it. There are two ’67 Camaros and a ’68, two ’59 Corvettes and a ’61, two ’66 Mustangs and a ’65. Inside the garage, Emr’s crew continue their work on the blue Cobra. They’re focused on finishing that car and the ’68 Camaro, Schofield’s baby, in order to bring both to the fall 2023 SEMA show for a public launch of the company, one year after Emr and Schofield were inspired in the same place.

But it’s another project that lights Emr up the most. Parked on a lift right next to the Cobra is a U.S. Mail truck, a Grumman LLV, with red and blue racing stripes and whitewall tires. Converting fleet vehicles to run on electricity—not just mail trucks but school buses, food trucks, and so on—is an entirely different business model and a potentially lucrative one that holds the allure of enormous scale with a single contract. As a boutique-size passion project, E-Muscle Cars isn’t anywhere near ready to tackle that kind of volume, but Emr can’t help grinning at the prospect.

For now, the mail truck is a curiosity, just the kind of oddball project that could get people’s attention and stoke their imagination at future exhibitions. “We’re going to hot-rod it out,” Emr says. “Put a flap in the side with a couple TVs. Maybe a Kegerator inside for trade shows.” Schofield sees two other auxiliary business opportunities that could emerge from the E-Muscle Cars effort: a repair shop for EVs and a battery-disposal service.

Out in front of the building, facing I-35, a twelve-foot-tall monster truck looms over the passing traffic. It’s a marvel of extreme automotive engineering from E-Muscle Cars’ officemates at Havok that requires an elevator to reach the cab—and a modified V8 gasoline engine to get it moving. Emr can’t hide another sly grin as he admits, “We already bought the website E-MonsterTruck.com.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Electrifying Performance.” Subscribe today.