Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins understood how much stress the governor was under. Last Wednesday, Jenkins and other local officials from across the state joined Greg Abbott on a conference call to discuss the coronavirus response. On the call, Jenkins wanted to avoid “second-guessing” the governor. But by this point, it wasn’t the days that mattered—hours did. Along with county judges from Harris, Travis, Bexar, and El Paso counties, Jenkins implored—practically begged—Abbott to break from his laissez-faire approach to handling the coronavirus crisis. He asked the governor to do as other states had done: close schools, limit every bar and restaurant in the state to takeout or delivery, and to make the mandate statewide, because, Jenkins argued, county-by-county restrictions were proving ineffective.

He pointed to a directive from the president to avoid gatherings of more than ten people. “If only Greg Abbott could get to where Donald Trump is,” Jenkins told me last Wednesday. “Donald Trump no less. This is the same man who said this was a hoax earlier this month.”

A few days before the call with the governor, Jenkins had met with 26 local officials within Dallas County to tell them he would be temporarily limiting bars and restaurants to takeout and delivery service. All but three tried to talk him out of it. There had to be a way to stay open and keep people safe, they argued. But Jenkins stood firm. And in Texas, state law grants enormous administrative control, during times of public crisis, to county judges—the highest elected county leaders.

The pressure on the governor seems to have worked: the morning after the call, Abbott issued an executive order closing schools, banning dine-in service at bars and restaurants statewide, and limiting gatherings to no more than ten people. But as the weekend rolled around, it became clear to Jenkins that more was needed. He now wanted the governor to implement uniform “shelter-in-place” rules for all of Texas. After Abbott neglected to issue such orders on Sunday, Jenkins quickly implemented them himself in Dallas County, becoming the first county judge in Texas to do so. Shortly after Dallas, Bexar, Travis, and Harris counties issued similar orders. “The leaders who are not at the point of the spear think these decisions are shocking and controversial,” he told me. “But then everybody else follows and those things become the norm.”

In normal times, Texas county judges preside over the county commissioners’ court and serve as budgeting officers. But when things turn atypical, county judges also handle disaster response and emergency management. Over the years, Jenkins has developed a playbook for handling public health crises that’s guiding him now: stay calm, engage the media, follow the science, be compassionate. “You might [also] try the ninety-first psalm,” he said, which reads, in part, You will not fear the terror of the night. “[It] is what I read first thing when I got up this morning.”

Clay Jenkins, who grew up in Waxahachie, is one of the most even-keeled politicians in Texas. His voice sounds like loud whispering, and he speaks in a slow, measured pace with a thick drawl. In the past week he’s led multiple half-hour-long press conferences in which reporters have hammered him with rapid-fire questions about how testing is going to work, the grim economic consequences his decisions will wreak on small businesses, and what is guiding his general approach to COVID-19.

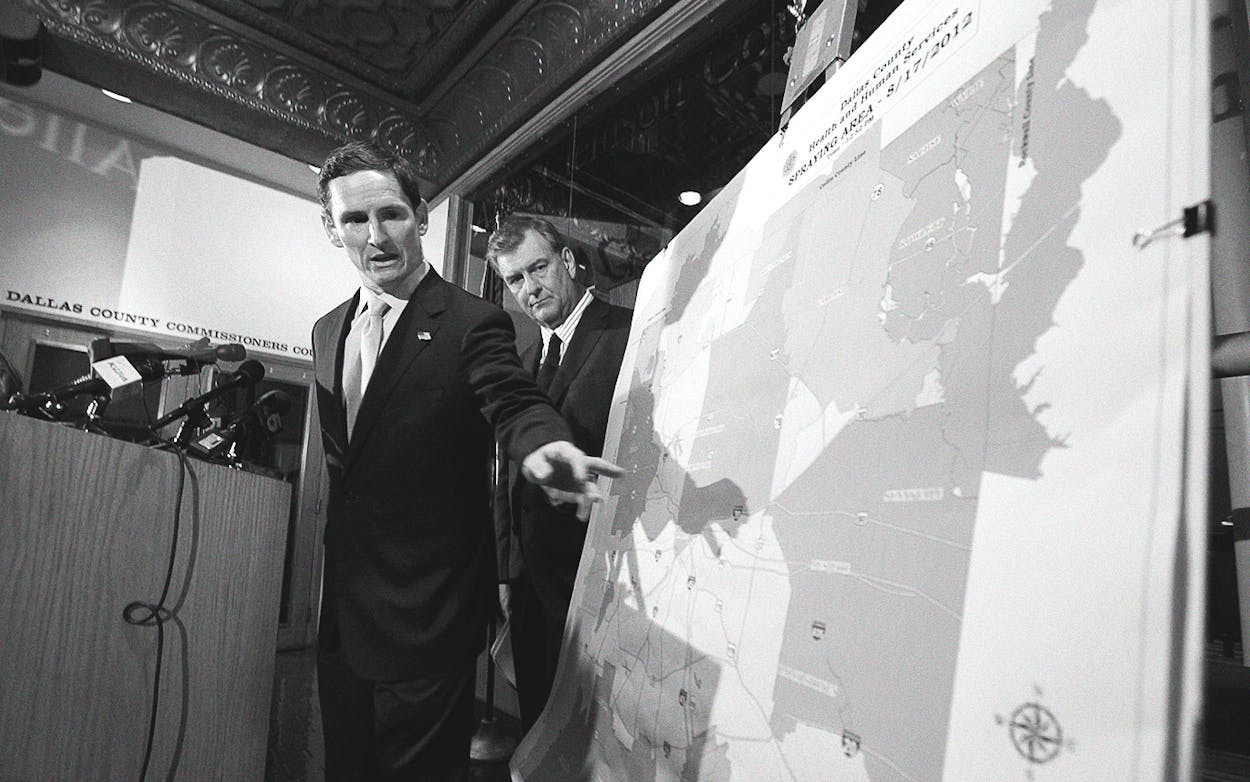

The main thing, though, is that Clay Jenkins shows up. In 2012, during Dallas’s mosquito-borne West Nile virus outbreak, he rode in the back of a pickup truck spraying the city with insecticide. In 2014 when, over a six-week span, two nurses contracted the Ebola virus and about two hundred people were monitored, Jenkins went to the apartment of Thomas Eric Duncan, who would become the outbreak’s sole fatality, without wearing protective gear. Afterward, he personally drove three of Duncan’s live-in relatives to a new temporary home.

His intention was to quell fear: Duncan’s relatives were asymptomatic, Ebola couldn’t spread through the air, and if the highest elected official in Dallas County wasn’t scared, the public shouldn’t be either. That was the judge’s thinking, at least. His wife Chrissy might have felt differently—she didn’t know about his plans until seeing it on live television.

Now that radical social distancing is the new reality for the foreseeable future, Jenkins’s hands-on leadership style will need to be metaphorical. “It’s a balancing act, always,” he said. “When you’re in a metro area of 7.6 million people the emotions and the way people deal with things will always rub together.” He says his chief responsibility to the public is the same as it was during Ebola: Stay calm.

“You are bombarded by people who are scared, and so they’re loud and they’re angry and they’re accusatory and mad because something that should have happened for them didn’t happen,” Jenkins told me. “As the leader, if you’re not calm, it doesn’t set the table for others to be calm.”

Jenkins’s approach is also to keep lines of communication open with members of the media and the public, sometimes theatrically. When it comes to media relations, Jenkins is setting the pace for public figures in Texas. Mike Rawlings, who was the Dallas mayor during the Ebola scare, said accessibility is crucial, and that his team erred on the side of overcommunicating with the public back in 2014. When they didn’t have answers, they admitted it. “Human beings are very practical. They’re much smarter than we give them credit for,” Rawlings said. “And when people don’t understand what’s going on, or why there are missteps in the testing process, it breeds more anxiety.”

But unlike prior crises, the coronavirus outbreak has not been readily contained. Jenkins’s role now isn’t just reassuring people; he also must implement unpopular but necessary orders. Because the Texas Legislature decided again in 2019 not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act—a decision Jenkins characterizes as “terrible”—Dallas County alone has around half a million uninsured people. Jenkins is particularly worried about uninsured people waiting until they’re near needing hospitalization and desperate to seek testing or medical help, and spreading the disease beforehand at their places of work—a factor in his decision to implement the shelter-in-home order. “We have to follow the science,” Jenkins said. “At this point, I have to put public health over the very real economic harm that it causes to employees. I’m very sympathetic to them. There are no easy decisions left.”

On Tuesday, amid growing pressure from health experts and state officials, Abbott hinted he might be willing to impose tighter statewide rules. “It’s clear to me that we may not be achieving the level of compliance that is needed,” he said during a press conference in Austin. But he still didn’t issue “shelter in place” orders.

Late last week, I asked Jenkins if there was anything he wanted to say to young people in the state who might not be abiding by social distancing guidelines. “Right now, we have people who are your age, in Dallas County, with this virus laid up in hospital beds,” he said. “I know you think you’re invincible. You’re wrong.”

Then he corrected himself.

“Well, I won’t say that, because you can’t tell young people they’re wrong. I know you think you’re invincible out there, but this is ‘Operation Protect Nana and Grandpa.’ That’s your mission, and you need to follow it.”

As we cover the novel coronavirus in Texas, we’d like to hear from you. Share with us your tips or stories about how the outbreak is affecting you. Email us at [email-hidden].

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott

- Dallas