There was never enough for Midland oilman Clayton Williams. Never enough crude and gas to extract. Never enough ranchland to graze. Never enough groundwater to exploit. Never enough wealth. “Money is how you keep score,” he once told journalist and social critic Vance Packard. By that measure, Williams was a winner when he died in February at age 88, having reportedly walked away with $1.3 billion from the 2017 sale of his oil company.

Yet Claytie, as he was widely called, is better known among Texans for losing the 1990 gubernatorial election to Ann Richards, the last Democrat to occupy the Governor’s Mansion. At a campaign event following his GOP primary win, he made an offhand joke about rape to the assembled press. The remark branded him as a clueless good ol’ boy, and his big lead in the polls evaporated. By Election Day, Williams’s reputation was that of an uncouth buffoon.

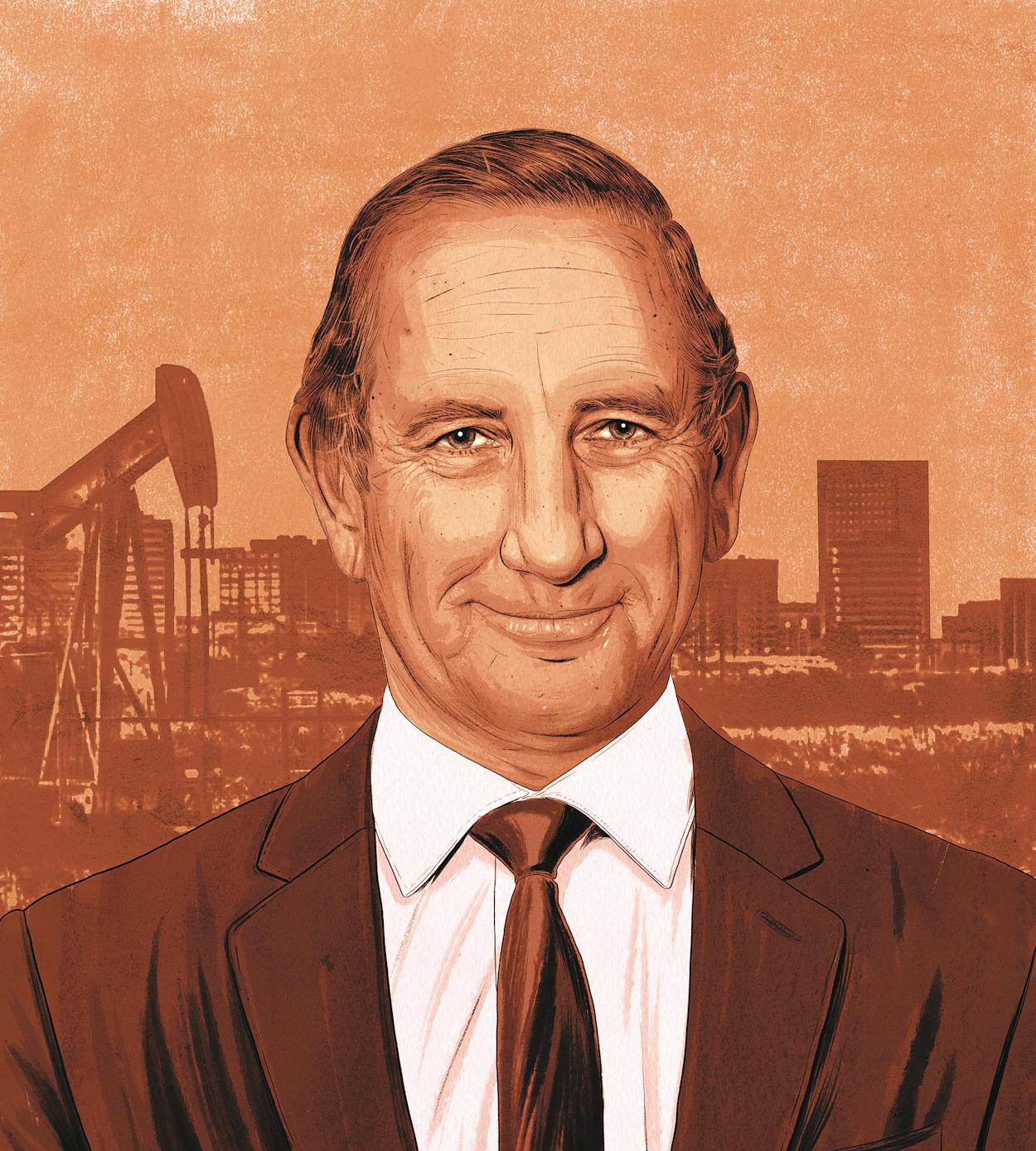

Still, he was easily likable. His dark brown eyes often sparkled, and his broad smile encouraged you to trust him. A 1954 animal husbandry graduate of Texas A&M University, Williams wept at the sound of “The Aggie War Hymn.” In his first business, selling life insurance policies, he boasted that he could get husbands to give up some beer money so that after they died, their wives could afford to live happily ever after with other men. Next he became a broker, buying natural gas and reselling it at a profit. The venture earned him enough money to invest in drilling his own wells. He set about building an empire, and at one time his company was the largest independent operator in Texas.

A plaza and an office tower in Midland bear the moniker ClayDesta—a mash-up of his name and that of his second wife, Modesta. There also were ranches, where he planted a hybrid grass developed at Texas A&M for his Brangus cattle. Williams always wanted people to like him, so he was stung by a 1985 Texas Monthly article in which his neighbors complained he was wasting precious water to keep his grass green and to reduce the dust on the roads of his ranch, lest it trouble the wealthy bidders attending his lavish annual cattle auction. Williams believed land was intended for human exploitation. He’d been raised on a farm near Fort Stockton where his father, Clayton Wheat Williams Sr., pumped so much groundwater that he dried up Comanche Springs.

Clayton Jr. became known statewide in 1984, when he launched ClayDesta Communications, one of Texas’s first wireless telecommunications companies, and was its chief busker in television commercials that played up his cowboy image. The following year, when legislation to deregulate AT&T threatened his competitive position, he galloped a horse up the lawn of the state capitol for a news conference opposing the bill.

He won the legislative battle, but at the end of that year, Saudi Arabia glutted the world oil market, and the price of West Texas crude plummeted. Savings and loan institutions across Texas went bankrupt. Unemployment statewide rose to 9 percent by the end of 1986. Williams was forced to sell ClayDesta Communications and his original gas company to pay down $500 million in debt. Even though the oil bust halved his worth, he still had $116 million to feed the political bug that had bit him as he lobbied the Legislature. For a man like Claytie, that meant running for the top job: governor.

The core issue for his campaign grew out of his son’s struggle with drug addiction. Williams promised to impose the death penalty for dealers of illicit drugs who caused the deaths of children. He wanted to set up a boot camp for youthful offenders so they could learn “the joys of busting rocks.” He poured millions of dollars of his own money into television ads to push that message, and the line became ubiquitous. In his speeches, he would mention the boot camps, say he was going to “teach them . . .” and then pause, with his hand cupped to his ear, as that salesman’s grin spread across his face. On cue, the audience would holler back, “The joys of busting rocks!”

In the Republican primary of March 1990, Williams swept aside three mainstream politicians, grabbing 60 percent of the vote. Meanwhile, Richards survived a brutal Democratic primary fight against state attorney general Jim Mattox. The bright West Texas stars seemed aligned to make Claytie the next governor. To celebrate, his campaign decided to invite the Austin news corps out to the ranch for a calving roundup. I was there to witness how badly it went—all because of fog.

Private jets shuttled the pack of journalists from Austin to Alpine, where we were spending the night. We were up around 4 a.m. on March 24, 1990, to ride out to the Happy Cove Ranch. The Brangus calves were to be herded into a corral for castration and branding. That turned out to be a metaphor for what was about to happen to Claytie’s campaign.

Three decades on, you may hear slightly differing reports from those present about the events of that day. My memory is that a thick fog had enveloped the ranch, and all we could see through the windows of the Suburban taking us there was a bit of dirt road, shrubs, and an occasional jackrabbit sprinting away. One of the journalist-filled vehicles got separated from the convoy and was lost for hours. The rest of us arrived at a large firepit where cowboys were cooking steak and eggs for our breakfast alongside a large pot of beans. There was no sign of Claytie or Modesta. Time started dragging by.

The fog was so thick that the men in the group who wandered several dozen feet away from the fire to relieve themselves were able to find their way back only by following the sound of voices. By the time the fog thinned and daylight began illuminating the land around us, I was sitting on a log, starting to nod back to sleep. That was when Claytie and Modesta came striding down the hill. They wore chaps, padded coats, and well-worn cowboy hats. Modesta saw the female journalists and announced, “If y’all need a bathroom, the house is at the top of the hill.” The women raced en masse toward the mansion.

Dead air made Claytie nervous. He was an obsessive talker. He began carrying on about the weather and the fog and how we couldn’t start until the fog lifted. Otherwise, we would miss calves in gullies and have to do the entire roundup over again. He filled a blue tin cup with beans, sat down on a metal folding chair, rocked back on the hind legs, and kept talking between bites. Nothing to be done but wait, he said. Get another cup of coffee, another cup of beans. Bad weather is like rape, he said: “If it’s inevitable, just relax and enjoy it.”

One of his aides instantly snapped, “That was off the record.” Huh? Was there a ground rule about the event that we’d missed? It was enough to create a few minutes of confusion, during which Williams left for the roundup. By the time we’d all agreed we were on the record, the women had returned and been filled in on what Claytie had said. We wouldn’t have a chance to confront him until dinner that night at an Alpine steakhouse. By then, the comment was already national news, thanks to the Associated Press, with myself and two other male reporters as the official witnesses.

When we asked Williams about the remark, he was apologetic to anyone who had been offended, but he was not contrite. It was “just a joke” made among men at a campfire. “That’s not a Republican women’s club that we were at this morning,” he said. “It’s a working cow camp, a tough world where you can get kicked in the testicles if you’re not careful.”

The #MeToo generation may be amazed that Williams’s campaign didn’t collapse immediately, or even the following month, when he admitted to patronizing prostitutes as a young man because it was the only way to get “serviced” in the West Texas of the fifties. Even today, the rape joke is often cited as the cause of his loss. It wasn’t—well, not the only reason, at least. Nearly six months after he made the remark, Williams led Richards in a Houston Chronicle statewide poll 48 percent to 33 percent. That might be because versions of the joke had been shockingly common. I’d heard it before, in my high school locker room. In 1976 the National Organization for Women organized a protest against a New York City television station when a weatherman told the joke on air. Just two years before Williams made national headlines, famed basketball coach Bobby Knight likewise received widespread criticism for uttering it during a network TV interview.

As the 1990 general election began, Texas remained in the midst of a recession, even if the worst was over. Oilmen had gone broke. New office towers sat empty. Claytie ran to “make Texas great again” and promised to govern with “traditional values.” Meanwhile, Richards envisioned a “New Texas” that broke the good ol’ boys’ network and empowered black and Hispanic voters, as well as women. She was politically savvy. He was naive. Williams once told me politics is a “parlor game for adults.” Richards was famous for saying Texas politics “is a contact sport.” She was about to teach him the joy of having his rocks busted.

Richards cast Williams as a chauvinist. “Rape is not a joke. It is a crime of violence,” she told a gathering of Democratic women. “It is time we had a governor in the state of Texas who recognized that women are not cattle, that they are not there for servicing.” Meanwhile, Claytie didn’t do himself any favors with his public remarks. When the Richards campaign predicted that she was closing the gap, Williams quipped that he hoped she “hasn’t started drinking again.” He also bragged that he was going to “head her and hoof her and drag her through the mud.”

Then Richards started comparing Williams’s businesses to those of New York developer Donald Trump. “The guy’s a Donald Trump in a cowboy hat, selling one failing business to shore up another,” said campaign manager Mary Beth Rogers. Claytie defended his business and said he was proud that he had shown integrity rather than using Trumpian tactics like junk bonds and bankruptcies to solve his problems. But Richards’s attacks kept coming, especially about questionable lending practices at ClayDesta National Bank. At a Dallas event they both attended, Claytie refused to shake Ann’s hand—at that time in Texas a serious breach of the unwritten rules of chivalry. He started to lose the support of Republican women.

The final straw had nothing to do with gender. Throughout the campaign, Richards and the media had demanded that Williams release his tax returns. He refused. On the Friday before the election, a reporter asked Williams if there was ever a year when he hadn’t paid taxes. Sure, he replied: in 1986, the year of the oil bust. Here was a wealthy oilman who had poured $8 million of his own money into what now looked like a vanity race for governor, and just four years earlier, he had paid no federal income taxes.

“It turns out he’s not such a red-hot businessman after all,” Richards told a group of Dallas supporters. Her campaign quickly churned out a radio commercial. “Millions of average Texans paid taxes while he took advantage of loopholes for the rich,” the ad said. “We ended up paying our share . . . and his.”

Ann Richards won. As Williams conceded defeat, some of his supporters chanted for him to run for governor again in 1994. “I’m an Aggie,” Williams replied, “but I’m not crazy.”

Ann’s New Texas turned out to be as fragile as the fog that once enveloped the Happy Cove Ranch. She served only one term, and then Republicans came to dominate Texas politics. Evangelical religious conservatives and tea party politics pushed Texas further right. Richards endured, though, as an icon. There were documentaries and plays about her. Claytie faded back to Midland as the man who told “the joke.”

That was a tough chew for Williams, a man who cared deeply about what people thought of him. The rape joke branded him for the rest of his life. Republican presidential candidate John McCain had to cancel a 2008 fundraiser hosted by Williams because of political blowback. In 2017 someone spray-painted a version of the joke onto the steps of the Clayton W. Williams, Jr. Alumni Center, on the Texas A&M University campus. If there was a list of stupid things politicians had said about sex or rape, Claytie’s comment almost always led the list. The joke featured prominently in seemingly every obituary written about the oilman.

The times changed. But Claytie never caught up, never really understood why his quip wasn’t funny beyond his circle of longtime associates. He once told the Midland newspaper that he tried to use humor to get past hardships. “The only place a sense of humor does not apply is politics.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Obituaries

- Ann Richards

- Midland