Don Huffines paid a lot of money to speak at the Conservative Political Action Conference, but he comes on stage like a man who, having been hit just offstage by a falling piano, is suffering from transient global amnesia. “Let me ask you something: why are we here?” he asks his audience. “What is a conservative?” What is action? What, for that matter, is a conference?

We know what CPAC is, at least. It’s the place where, for decades, American movement conservatives have gathered to hammer out what it means to be a conservative. As grassroots conservatism gained prominence and power, CPAC—a production of the American Conservative Union, which was founded shortly after Barry Goldwater’s landmark presidential-campaign defeat in 1964—provided a place for neocons, paleocons, Christian conservatives, right libertarians, hawks, Randians, napkin economists, and what have you to meet, get drunk, and figure out what they have in common.

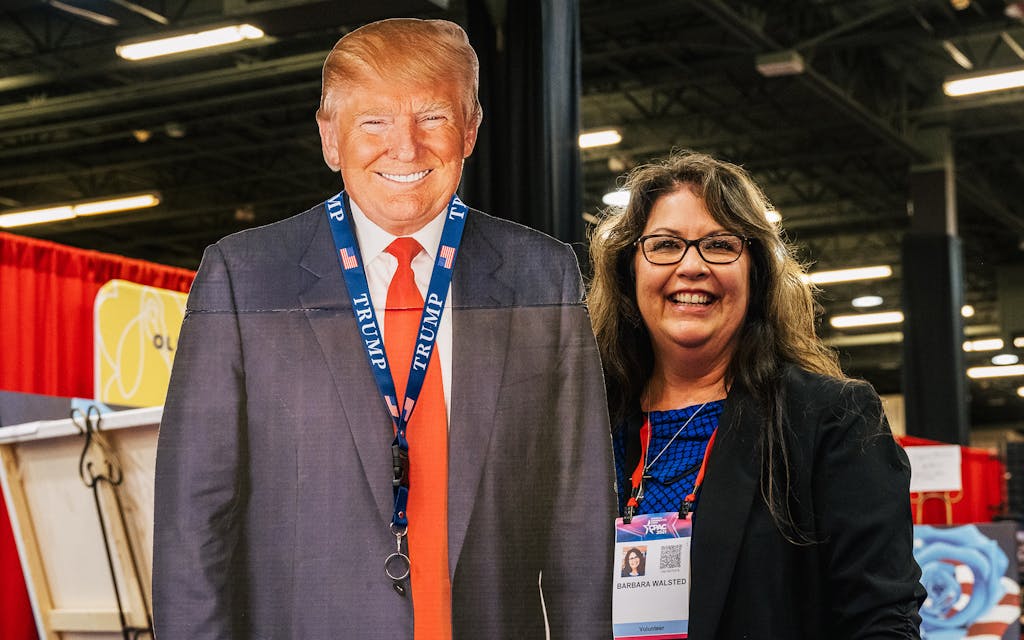

For many years, CPAC was held inside the Beltway, close to the center of power. During Trump’s presidency, it moved to Florida, and it began to multiply. The American Conservative Union began holding spinoff CPACs in foreign countries: Japan, Australia, Brazil, South Korea. This weekend, they held one in a stranger nation: Texas. At the sprawling Hilton Anatole northwest of downtown Dallas, several thousand attendees gathered to consider the past, present, and future of the movement, attending panels and listening to speakers.

Huffines’s campaign for governor of Texas is a sponsor for the convention. Seemingly in return, he is awarded a roughly ten-minute speaking slot on Saturday morning, when the room is about half full. “Have you ever met a Republican that didn’t say he was conservative? No. They all say they’re conservative,” says the former state senator. “And guess what? Almost all of them are liars. They’re liars!”

Chief among the liars is Governor Greg Abbott, Huffines declares. Whatever “conservative” is, Abbott is not that. He must be replaced. “Patriots, grab your rusted swords of liberty. Unsheath them from your sticky scabbard! Help me cut the chains of government. Awaken!” he says, spreading his arms wide for emphasis. “Awaken the sleeping sheep from their slumber!” The applause is respectful. The following day, he holds an ice cream social for activists in the Morocco room upstairs.

The history of American conservatism is inextricably bound up with the history of Texas. But there’s a tension here, just as there is nationally, between ideological conservatism and the personality-driven appeal of Trumpism. In 2016 Ted Cruz, who was and mostly still is beloved by many ideological conservatives in Texas, splattered like a bug on Donald Trump’s windshield. The discomfort with that never completely went away, even though nearly all of the conservatives learned to like the Donald in their own ways. What’s left of the right? Is Texas still at the forefront of the movement?

Perhaps not. The most notable thing about CPAC Texas, the year’s second and secondary American CPAC—CPAC 2: Tokyo Drift—is who is not here. Abbott is the most conspicuous in his absence, which Huffines makes sure to note. The governor has a plausible alibi: the special session began last Thursday. On the other hand, he decided when the session would commence. Was it a coincidence that he created a scheduling conflict between the conference and the Legislature? When the year’s first CPAC took place in Florida in February, Governor Ron DeSantis, a 2024 favorite and Abbott rival, had one of the most high-profile speaking slots. His speech got rave reviews.

Abbott is the most powerful and popular elected Republican in Texas, an ambitious man who’d like to be considered in the same category of presidential contenders as DeSantis. CPAC is one of the best chances he’ll get to speak directly to conservative activists outside of a party convention. But it seems clear why Abbott is missing the conference: he wouldn’t be welcome here. When Huffines tries out his Abbott attack lines—that he is beholden to Dr. Anthony Fauci, for example—the audience registers its approval with loud boos and cheers. Former Florida congressman and recently departed Texas GOP chair Allen West, another Abbott primary opponent, is here too, working the crowd and appearing at a private event with Florida congressman Matt Gaetz, currently in trouble for allegedly paying for sex with an underage girl (he denies the charges). “I look out at this audience, there’s quite a few white folks out there,” West consoles the crowd. “But, you know something, I don’t feel one bit oppressed. I don’t feel like a victim.”

The most powerful state Republican to attend is Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, who helps open the conference with American Conservative Union chairman Matt Schlapp. But even then, their exchange centers on the fact that the main CPAC moved to Florida, not Texas. Schlapp jokingly apologizes. Patrick makes an offer. “It would be the perfect place for CPAC to move to and establish their headquarters right here in Texas!” he says. Schlapp says he’ll need to consult his board.

Land commissioner George P. Bush, currently running against indicted Attorney General Ken Paxton, is a sponsor of the convention like Huffines, but he doesn’t speak. He, too, would likely be booed. (Paxton does address the crowd. He tells stories about his personal exchanges with Trump.) Agriculture commissioner Sid Miller, disliked by a surprising number of Texas Republicans, is present, as are a number of Texas congressmen, among them Michael Burgess and Louie Gohmert. That’s about it for Texas politicians.

Senator Ted Cruz isn’t in attendance either. Whether or not Cruz plans to run in 2024, he’d surely like to be considered. This year, neither Cruz nor Abbott nor any other Texan registers in the CPAC straw poll of presidential contenders. Trump is the clear winner, picking up 70 percent support from the attendees, with 21 percent backing DeSantis. If Trump were not to run in 2024, 68 percent say they would support DeSantis, with 5 percent backing Trump’s former secretary of state Mike Pompeo, and 4 percent favoring Donald Trump Jr. (In the poll, Trump Sr. registered 98 percent approval.) The message is clear: right now the center of gravity of American conservatism sits in Florida, somewhere between the governor’s mansion and Mar-a-Lago. Texas feels ancillary, even at CPAC Texas.

There’s another prominent absence at the conference: the story of conservatism itself. Since the first conference in 1974, CPAC has been a place where the conservative movement is shaped, and its shared history has always been a key part of what binds the various factions together. Conservatism in its most basic sense, after all, is about preserving an inherited past.

On Saturday afternoon, Glenn Beck, the conspiracy-prone pundit, pulls out his trademark blackboard and a treasure trove of artifacts from American history—FDR’s wheelchair, Jesse Owens’s Olympic torch, a rifle seized from Native Americans—to articulate his grand narrative of the story of the country, which he says the left is warping beyond recognition. “Critical race theory” is the hot topic of the whole conference, and the “1619 Project” is repeatedly denounced. But there is almost no talk about the history of the conservative movement before 2016, and as the days pass this becomes stranger and stranger. Ronald Reagan, who was a godlike presence in the movement as late as 2012, receives a few brief mentions and a quick place in a video montage that fills time on the floor. The Bushes, instrumental figures in conservatism both in Texas and nationally, receive even fewer mentions, if any. (I heard none from the floor.)

On Saturday afternoon, a panel with an audacious title sits on the main stage: “Buckley, Reagan, Trump: Now What? The Future of Conservatism.” That’s William F. Buckley, of course, the august founder of National Review. Finally, someone—Florida representative Greg Steube and two activists—would get to the bottom of things. But Reagan doesn’t come up at all. Buckley is mentioned once, by the moderator, when he asks if Buckley’s axiom, that conservatives ought to “stand athwart history yelling ‘stop,’” is outdated. Yes, the panelists say. Conservatives need to go on the offensive, they argue. Nothing else of substance is said about the movement’s past—nor is much said about the movement’s future. There is only the present, dominated by the man who speaks at the end of the conference, he of the 98 percent approval rating. Trump’s speech is the only time the hall is close to full.

Perhaps only egghead liberals care about Buckley now. But the absence of heroes from before our Year Zero, 2016, is evidence of a movement adrift. What will conservatism look like after Trump leaves the scene? If the crowd in Dallas is any indication, that could be a very long time from now.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Donald Trump

- Dallas