After this weekend’s mass shooting in West Texas that left seven dead and over a dozen more injured, the pressure is on leaders in Texas to do something about the crisis facing our state. Four of the ten deadliest mass shootings in U.S. history have occurred here—one of them just over a month ago in El Paso—and the frequency with which they’ve begun happening means that it’s no longer possible to just wait for the news cycle to move on.

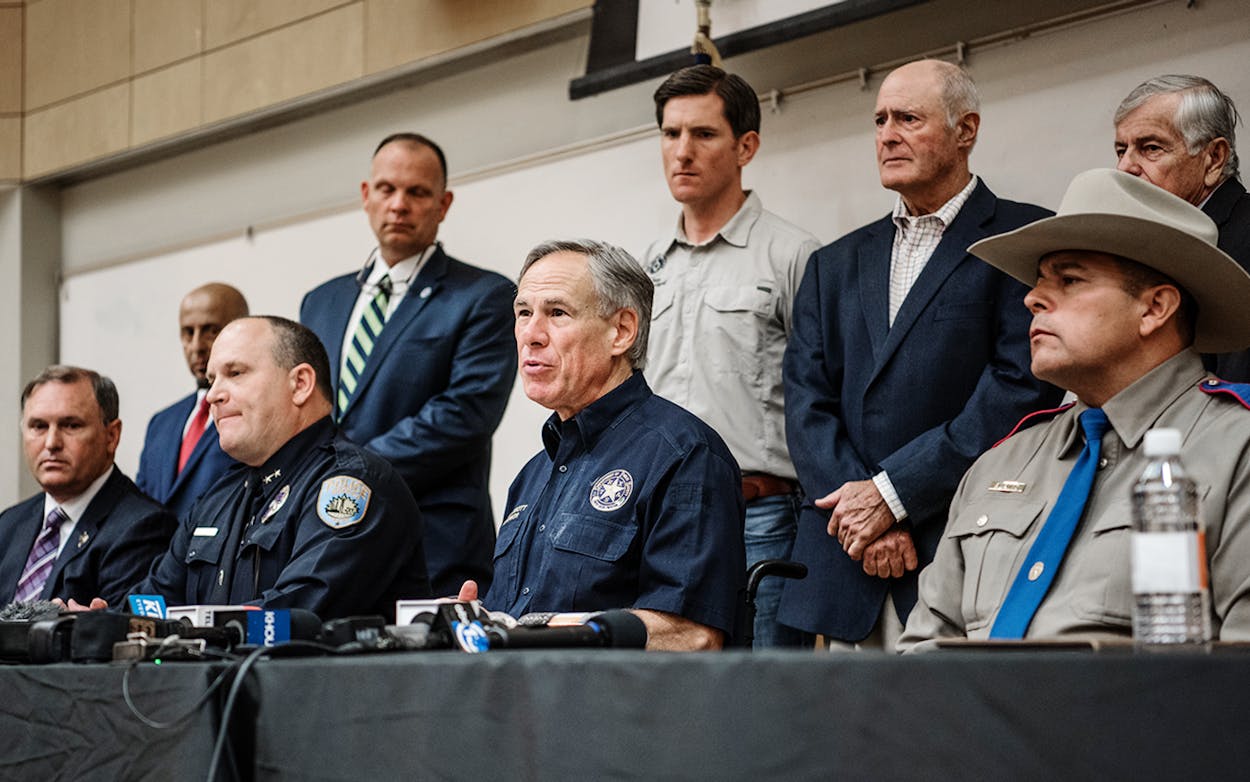

Texas Republicans have generally been slow to address the problem. For example, Representative Matt Schaefer, in a viral Twitter thread, vowed that “as an elected official with a vote in Austin,” he’s in favor of voting “YES to praying for victims” and “YES to praying for protection,” but “NO” on anything he could use his power in the Legislature to do. Nonetheless, Governor Greg Abbott is pushing an action that can only be taken by someone with the ability to make laws: He plans to call for “expedited executions” for mass shooters, in the event that they’re apprehended after their rampage.

That is a curious proposal, given the circumstances of the men responsible for recent high-profile mass shootings in Texas. The deadliest of them, the November 2017 church shooting in Sutherland Springs, was carried out by a man who expedited his own execution by shooting himself in the head after murdering 26 people in their house of worship. Last year’s shooting at Santa Fe High School was carried out by a teenager—who can’t be executed, per the U.S. Supreme Court—while the shooter in Midland-Odessa was killed by police upon being apprehended.

That leaves only the El Paso shooter, who was captured alive as a legal adult. But in his rambling screed explaining his actions, he goes into great detail about how he felt about the prospect of surviving the mass shooting:

My death is likely inevitable. If I’m not killed by the police, then I’ll probably be gunned down by one of the invaders. Capture in this case if [sic] far worse than dying during the shooting because I’ll get the death penalty anyway. Worse still is that I would live knowing that my family despises me. This is why I’m not going to surrender even if I run out of ammo. If I’m captured, it will be because I was subdued somehow.

The worst part of being captured, the man who murdered 22 people wrote, would be having to live with the knowledge that his actions meant that his family hated him. Instead, he hoped to die as quickly as possible. Expediting his execution, as Abbott suggests, would be anything other than a deterrent to someone whose desire is to avoid the pain of living with what he did—if anything, based on the shooter’s own words, it would ease his punishment.

That’s surely not Abbott’s intent, though he hasn’t explained the rationale for his proposal, so we can’t know for sure why he even thinks expediting executions are necessary or effective. Regardless, it’s hard to see the proposal as anything other than an empty gesture at solving mass shootings. Most mass shooters, especially the kind who carry out their attacks in public places with a high body count, die before being apprehended. (Of the nine mass shootings in 2019 that killed at least three people in public, six of the perpetrators died at the scene.)

Vowing to more quickly and efficiently execute people, in the wake of a shooting in which the perpetrator is already dead, is the sort of action you take when you’re scared to take action. Our leaders are a “NO” on the most obvious—and popular, even in Texas—solution of passing laws that make it harder for people who might carry out a mass shooting to get their hands on guns. With popular gun safety proposals off the table, what we’re left with is speeding up executions. We’ll see how effective that is after the next shooting, I suppose.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Execution

- Crime

- Greg Abbott