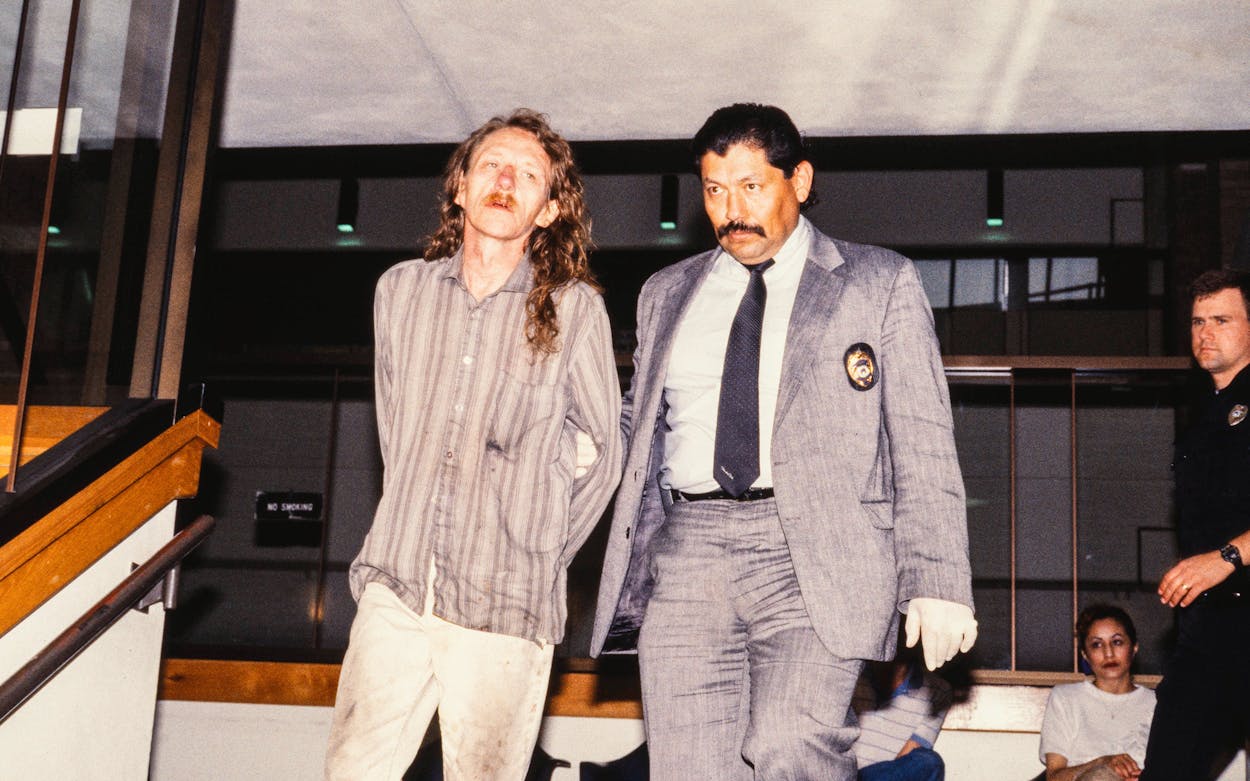

Hector Polanco was a legend—in more ways than one. He joined the Austin Police Department in 1976 and spent years as a patrolman before becoming a homicide cop. Polanco was handsome and charismatic and often found himself in the pages of the Austin American-Statesman—nabbing bad guys, rescuing infants, and, in January 1978, five weeks after University of Texas running back Earl Campbell won the Heisman Trophy, writing him a warning ticket for speeding. By August 1991, Polanco had worked himself up to being a supervisor in the homicide division, with 45 commendations over his long career and a reputation as a top-notch investigator.

But Polanco received complaints too, including eight that made it through official channels, of which he was later cleared: five for excessive force, two for verbal abuse, and one for misconduct. At a chaotic 1983 protest against the Ku Klux Klan, he was videotaped reaching over other cops to beat a protester with his billy club. It got him a reprimand from the chief of police.

Then came the infamous yogurt shop murders, after which Polanco’s reputation took its deepest dive—and kept tumbling. On December 6, 1991, four teenage girls were shot and set on fire inside an I Can’t Believe It’s Yogurt store in North Austin. After the investigation was badly botched by an overworked and undermanned police team, Polanco was appointed to lead a task force composed of men and women from the APD; the FBI; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms; the Travis County Sheriff’s Office; and the Texas Department of Public Safety. But seven weeks into their investigation, Polanco was booted off the unit for eliciting false confessions from two suspects. Six months later he would be kicked off the APD entirely for lying under oath in another case. In early 1992, when Polanco’s name showed up in yet another bad bust—he had put a suspect through two marathon interrogation sessions and badgered him into confessing to a murder he didn’t commit—city leaders announced an unprecedented investigation into police misconduct. During the inquiry, investigators turned up yet another case. This time Polanco had coerced an innocent college student to confess to a rape and murder he hadn’t committed.

The four girls’ murders at the yogurt shop went unsolved until 1999, when four teenage boys were arrested after two of them underwent protracted interrogations and then confessed. But while the confessions were full of details about the murders, the interrogations were also full of police officers yelling and swearing at the boys—one cop held a gun to a suspect’s head. Two of the boys were found guilty, but their verdicts were eventually overturned for procedural reasons and then dropped altogether when DNA was found on the body of one of the girls that matched that of none of the boys.

Polanco was retired by then, but for many in the law enforcement community, his influence remained. “Hector Polanco is the father figure of all the detectives who have come in his stead,” Berkley Bettis, the attorney of one of the boys Polanco interrogated, told me back in 2000, when I was reporting on the yogurt shop murders. “They have the same convict-at-any-cost mentality.”

That year, I also got to see Polanco’s effect on others when he testified at a pretrial hearing. There was no overstating the man’s impressive bearing, I wrote: “The much-decorated lieutenant (who until recently was on extended medical leave and would not be interviewed) shambled slowly into the room, looking like Orson Welles in Touch of Evil, his huge frame supported by crutches, while everyone—the families of the girls, the families of the suspects, and even the police—stared with a mix of awe and fear.”

Polanco was a legend, all right, but not always for the right reasons. (He declined to be interviewed for this story too.) And while many of the men who confessed to him over the years were never charged, others were not so lucky. One of those men, Allen Andre Causey, was convicted of murder back in 1992, amid the chaos that followed the yogurt shop murders, and spent more than three decades behind bars for a confession he signed after a Polanco interrogation, one he said involved threats of lethal injection and prison rape. Causey always insisted he was innocent and that he had been tricked into signing the confession.

Last week, on November 27, Causey had another day in court, in front of Judge Chantal Eldridge in Austin. He’s 58 now, his hair short and graying, and he sat next to his lawyers with the Innocence Project of Texas wearing black slacks and a black sweater. Causey was granted a new trial last year; this week’s hearing was on a writ of habeas corpus filed by his lawyers that claimed he is legally “actually innocent.” The proceedings came about in large part because last year investigators for the Travis County district attorney’s office found several boxes of documents revealing the details of the 31-year-old police-misconduct investigation—and all the resulting false confessions. Prosecutors in the DA’s office saw a pattern in those interrogations that seemed to be repeated in Causey’s case—especially the presence of Polanco—and began working with Causey’s defense team. On Monday, both sides presented that evidence, as well as new evidence that pointed to another suspect, one whom police had initially investigated back in 1991 but then discounted.

Causey sat quietly during the proceedings, intently listening to the witnesses and the lawyers. The man he claimed coerced his confession was not called to testify, but no name was said more often during the day than that of Hector Polanco.

On August 11, 1991, the body of Anita Byington was found in the grass outside an East Austin apartment complex. She had been beaten to death with a concrete rain diverter; her car was found five miles away. A crime scene bystander told police that she had noticed a Black man slowly driving a maroon Oldsmobile Toronado around the parking lot, rubbernecking. Officers tracked him down. Andre Causey was 26, a high school dropout with no criminal record who lived part-time with his girlfriend, Dellanda Harrell, at the apartment complex. Two officers, Mike Huckabay and Bruce Boardman, asked him some questions about the car, which he said he had borrowed from a friend. The officers, curious about why he had been acting suspiciously at the scene, asked him to come to the station to answer some questions.

They arrived at 8 p.m. After 30 to 45 minutes of questioning, Huckabay and Boardman decided Causey was lying about the car and might be also lying about the murder. They read him his rights and turned up the heat. They were also joined by their supervisor, Hector Polanco. Causey insisted that although he and his friend Bobby Harrell Jr., Dellanda’s brother, had been smoking crack at a nearby apartment, they had nothing to do with the murder. The police, though, developed a theory: a drug deal had gone bad in which Causey and Harrell had killed Byington.

Between 2:30 and 3 a.m.—after more than six hours of interrogation—Causey signed a confession, typed by a fourth policeman, that he and Harrell had beaten Byington to death after she had cheated Harrell out of some cocaine. The police arrested the two men. Causey immediately recanted the confession when he realized what was in it. He told his lawyer he hadn’t even read it—he had been a slow reader in school, in special ed classes—and said the officers hadn’t read it to him. Causey insisted the cops told him that the document only said they had read him his rights and hadn’t beaten him. He had been exhausted and all he wanted to do was go home, so he signed. He swore he’d had nothing to do with the murder.

It turned out that police had another suspect, a man named Kevin Harris, who was the last person to see Byington alive. They’d had sex that night; Harris swore it was consensual. He was interviewed, but once the cops had a confession from Causey, they had their man.

Seven months after Byington’s murder, Polanco was thrown off the yogurt shop murders task force. The move came after suspicions emerged that he had coerced false confessions from two suspects in the murders. One was named Tony Bell, who, when later interviewed by a federal agent, admitted he had lied but said he did so only after Polanco issued threats, including that he would have his sister raped. The other suspect, Alex Briones, had already been arrested for a San Antonio murder when, after talking with Polanco, he verbally confessed to killing the girls, though without much detail. When other officers became suspicious, Huckabay interviewed Briones again, though the suspect kept asking to speak to Polanco in private. Briones finally signed the confession but then failed a polygraph—and later said that Polanco had threatened him and told him what to say.

In the wake of the Briones revelation, the district attorney’s office and then APD’s internal affairs division began looking at other cases Polanco was involved in. One involved a man named Billy Gene Davis, whose girlfriend’s father had called the APD on August 8, 1990, to report her missing. Polanco put Davis through two marathon interrogations over consecutive days (for roughly eleven and sixteen hours, respectively), getting two different confessions to murder. But then, on August 18, the missing woman called her father from Tucson, Arizona—very much alive.

Another case involved the murder of William Redman, a correctional officer, in February 1991. A man named John Salazar had initially been questioned by Sergeant Brent McDonald, who got nowhere with him. Then Polanco got involved. Salazar later told members of the yogurt shop task force that Polanco introduced himself as “el Diablo” and started interrogating him. By the time Polanco was done, Salazar had signed a confession. Unfortunately for Polanco, fifteen minutes before Salazar confessed, other cops were getting confessions from two men who, two juries would later find, had actually committed the murder.

At those two trials, both Polanco and McDonald testified and denied taking a confession. But Salazar’s written statement was found three months after the proceedings. The APD charged Polanco with aggravated perjury and suspended him. He swore he was innocent—he later claimed he had forgotten about the statement—and chose to be fired so he could appeal. The APD gave McDonald a written reprimand; Polanco sued, alleging he was given a harsher punishment because of his Mexican heritage.

Polanco’s troubles came at an awkward time for the state’s prosecution of Causey. At a May 1992 pretrial hearing, Causey’s attorney Michael Etchison noted the official investigations of Polanco, which were front-page news in the Austin American-Statesman, and pointed out that Causey’s confession “appeared after Officer Polanco got involved. This raises a flag.” Etchison asked the court to force the state to turn over records of any questionable confessions taken by the four APD cops involved in Causey’s case; the judge eventually granted Etchison’s request, though the state never complied.

At the following month’s trial, Causey said Huckabay had been confrontational in the interrogation room—“I was just scared in my pants”—and when Polanco arrived, things got worse. Causey testified that Polanco was alone with him in the room for about an hour, and that Polanco choked him, threatened him with lethal injection, and promised that other inmates would “turn [him] out,” or rape him.

When Huckabay took the stand, he testified Polanco was never alone with Causey and that the confession came from his own mouth. Polanco swore he didn’t choke or threaten Causey or mention lethal injection or being turned out. He had never seen a “coerced confession,” he testified. “I always have told the truth.”

As for the confession, Causey insisted he didn’t read it—he reckoned the officers had typed it up while he dozed in the room—and testified that nobody read it to him. Etchison pressed him on why he hadn’t read something that he was signing. “Because I can barely read and I was under pressure. I was nervous, scared.” He said he took the cops at their word regarding what was in it because he hadn’t done anything wrong.

Unfortunately for Causey, a confession is just about the most powerful thing a jury can hear, because most jurors believe no one would confess to a crime they didn’t commit. These days, because of the hundreds of DNA exonerations over the past 34 years, we know that belief is misplaced. The truth is, false confessions are common. More than a quarter of those exonerations involved suspects who made false confessions; it turns out that when under pressure from persistent interrogators, innocent suspects (especially the young, the exhausted, and the semiliterate) will say just about anything.

But we didn’t know this in 1992, at the dawn of the DNA age. Though there was no physical evidence against him—and though Harris had left three prints in Byington’s car and could not be eliminated as the source of the semen on her blouse and underwear—Causey was found guilty and sentenced to fifty years in prison.

Four months later, on November 9, 1992, in a showing of just how bad things were in the APD homicide division, DA Ronnie Earle, Mayor Bruce Todd, and incoming chief of police Elizabeth Watson banded together at a press conference to announce an extraordinary investigation of the unit. “Specifically,” said Earle, “the police misconduct involves using improper methods to obtain confessions and statements, obtaining false and incorrect statements and confessions, and concealing evidence.” Watson sounded stunned. “It is shocking to me that there could be this breach of ethics that I see.”

Earle was careful to note that “this behavior is not the result of the work of just one person. . . . It appears to arise from attitudes among some criminal investigators of ‘anything goes.’” Yet the investigation had begun because of another bad Polanco case. In October 1992 a young man named Alva Curry had gone on trial for murder after confessing to police that he had taken part in a robbery and killing. He was found guilty, but the day after the trial, prosecutors were told by police that days before Curry confessed, a man named Bruce Bowser had also confessed—after two six-to-eight-hour interrogation sessions with Polanco and other cops. Bowser had recanted almost immediately and claimed that Polanco threatened to have his mother and grandmother killed by a man Bowser had robbed if he didn’t cooperate.

The new investigation of misconduct started with more than ninety cases, and after three months, officials whittled it down to eight. One of them involved Richard Osaze-Ediae, a Nigerian college student charged with murdering a young woman after confessing to Polanco that he had raped and killed her under the influence of crack cocaine. Osaze-Ediae told investigators that he only confessed because Polanco told him he was destined to be executed but that a confession would lead to a ten-year sentence. His case was eventually dismissed. When the final report was released April 2, 1993, Polanco’s name appeared in it three times, one of which indicated his failure to write police reports. Officers throughout the unit were also found to file incomplete reports or simply not file them at all, a practice which, the document noted, could lead to “concealing evidence possibly favorable to the accused.” The report also criticized the APD’s leadership. “It suspends belief that those in the chain of command above Sr. Sgt. Hector Polanco did not know what was going on in the homicide detail with regard to interrogation methods and incomplete report writing.”

By this point Polanco was appealing his firing over the Salazar case. He said he had forgotten about taking the suspect’s confession (a January 1993 newspaper story was titled “Polanco didn’t intend to lie, lawyer says”). In June 1993 an arbitrator put him back on the force, and he held a press conference and reiterated what he had always said: he had never committed perjury. “What I’ve gone through the last fifteen months,” he said, “I wouldn’t wish that on anybody.” He ultimately won $318,537 for his discrimination suit and retired in 2001 at age 49 with full benefits.

But Polanco would get little rest. That year had seen the release of two men he’d helped send away for murder in 1990, and one of them had a terrifying story to tell about Polanco and his interrogation methods. In October 1988 a woman named Nancy DePriest was killed at an Austin Pizza Hut. Two weeks later, two young men who worked at a different Pizza Hut—Christopher Ochoa, 22, and Richard Danziger, 18—went to her restaurant, bought a couple of beers, and toasted her. On the way out, Danziger chatted with a security guard, and suspicious employees called police, who picked up the two for questioning. Ochoa was a former high school honor student with no criminal record. But after two twelve-hour sessions with Polanco, Boardman, and Ed Balagia, Ochoa signed a confession that included important details about the murder. He implicated Danziger, pleaded guilty, and was sent to prison for life.

In 1998 another man confessed and was tied to the killing through DNA. The case was reopened, and Ochoa revealed—in an article he wrote for the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology as well as in numerous interviews (with everyone from ABC’s late-night news show Nightline to the Dallas Morning News and the Austin American-Statesman) why he had confessed to a brutal crime he didn’t commit. He told how Polanco walked into the interrogation room and announced that on the streets he was known as “el Cucuy,” or “the Bogeyman.” According to Ochoa’s account, when he said he knew nothing about the DePriest killing, Polanco pounded the table, yelled at him, and threatened him with the death penalty if he didn’t tell the truth. Once, Ochoa wrote, Polanco grabbed his arm and showed him where the executioner would insert the needle. As the hours went on, Ochoa became exhausted. Finally, when Polanco threatened to throw him in the local jail, where he would be “fresh meat,” Ochoa recalls, for the other inmates, he gave up. “I just wanted to go home,” he would later write. Polanco brought in a typewriter and began asking Ochoa questions. He put the young man through another day of interrogation, feeding him details about the murder. “My brain was mush,” Ochoa wrote. Finally, Polanco wrote out a statement and Ochoa signed it. He was taken to jail.

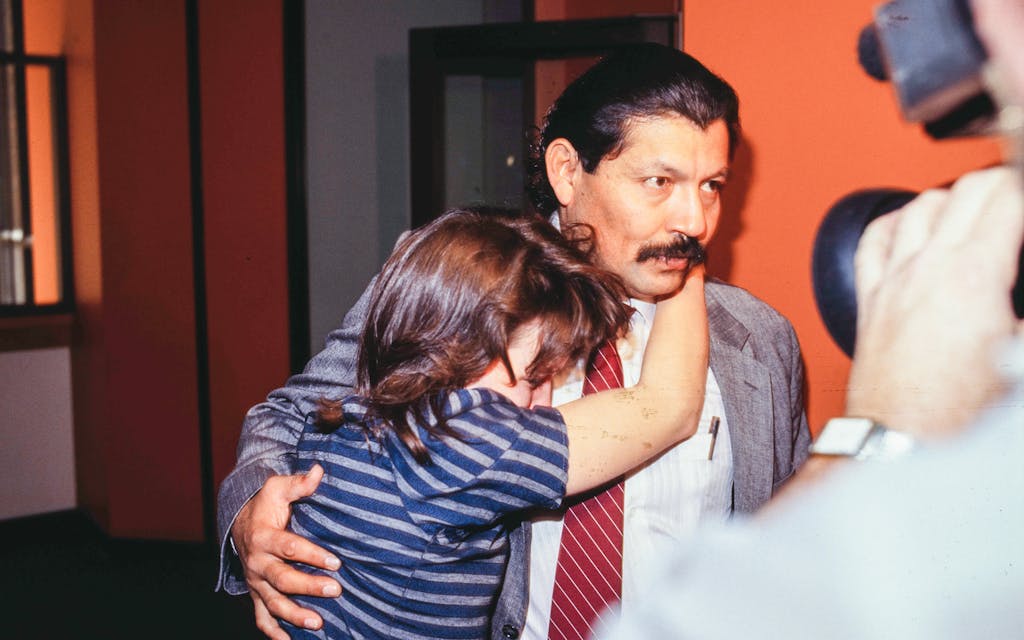

After being exonerated, Ochoa and Danziger sued the city of Austin and three of the cops, including Polanco. The city ultimately wound up paying $14.5 million to the two men. “I feel very bad for not having had the courage to stand up to the police,” said Ochoa.

Today, Andre Causey and Dellanda Harrell-Causey live in a red brick house on a quiet street in Elgin, about thirty miles northeast of Austin. They’ve been a couple for more than 33 years. They’ve been together—physically in the same space—for about two of those years.

Dellanda always liked Andre. Back in the day, he was low-key, quiet, and didn’t argue with anybody. They started dating after high school, and she returned to Austin after getting her accounting degree at Paul Quinn College, in Waco. When he was arrested, she was a bank teller. He was doing landscaping work, making $35 a day. They were opposites then and still are today—he’s quiet, with a graying goatee, laugh lines around his eyes, and a calm demeanor. He speaks softly in a deep drawl. She’s outgoing, chatty, and bubbly.

Though Causey had developed a taste for crack cocaine in 1991, he had never been in trouble before, never even been questioned by the police. When he was sitting in the interrogation room at the police department, he told me, he was terrified. “I was really lost, like, ‘This can’t be happening to me. I ain’t done nothing.’”

I compared his case to Ochoa’s—cops getting overly suspicious, asking him to come in for questions, homing in on him, badgering. The threats of execution, prison rape. “Polanco was really pissed,” said Causey. “He come in and he just started big-dogging: ‘You did it; we gonna get you.’ I’m like, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about; I ain’t done nothing.’ ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, you killed her.’ I’m like, ‘I ain’t done nothin’.’”

Later Causey would impugn himself for not at least trying to read the confession. “It was the wee hours of the morning,” he told me. “I was tired, ready to go home. In my heart and soul, I knew I hadn’t done anything wrong. They told me all I had to do was sign this, and I could go home. That was a lie.” His codefendant, Bobby Harrell, never had to go through what he did. Nine months after Causey was found guilty, prosecutors dropped the charges against Harrell for a simple reason: they had no evidence. “They just had to pin it on somebody,” Harrell told the Statesman after his 1993 release. “Andre just signed the wrong paper, and they set him up.”

After Causey was sent to prison, he and Dellanda maintained their bond. Dellanda would drive to visit him two or three times a month. She did it for her peace of mind as much as his. “Keep him going,” she said. “But sometimes I would feel down too. He’s an encouragement to me.” Sometimes she just needed to talk to him. He had always been even-keeled, and somehow even in prison he kept his composure. “He’s always been mellow, like, ‘I’m gonna ride it out.’ We just kept encouraging each other.”

In prison, Causey worked various jobs, and he learned to read. He taught himself with help from other inmates and earned his GED, or high school equivalency credential, in 2003. He worked on his writing by copying out love poems he had read in books from the library—or even poems friends of his in prison had written—and sending them to Dellanda. She kept them all.

Causey says he was turned down for parole fifteen times. “Keep the faith,” Dellanda would tell him. “We just have to wait and try again in two years.” Finally, after thirty years and three months, he was paroled in October 2022.

I asked Dellanda why she stuck with him all that time. “He was innocent, and I loved him. I tried to date other people, but they weren’t what I wanted. He had me spoiled from day one. I was waiting on him.” They got married in 2000 at the courthouse in downtown Austin when he was awaiting a court hearing and renewed their vows in June after he got out. For seventeen years she’s been an office manager for the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, based in Austin. He now has a job in a warehouse in nearby Hutto, pulling orders and shipping them.

“I don’t have no animosity toward the police,” Causey told me, “even though they’ve done what they did. It’s not going to serve me any good to go down that road. I always been laid-back and calm, and I’m like, I don’t wish nothing bad on nobody. I hate what they did to me, don’t get me wrong, but I don’t wish nothing bad on them.”

In 2022 Causey’s case was taken on by the Innocence Project of Texas, which alerted the Travis County DA about it. An investigator for the DA’s Conviction Integrity Unit subsequently found several file boxes of documents on the 1992 investigation into Polanco and the APD and shared them with Causey’s attorneys. They then filed a writ of habeas corpus presenting five grounds, including the claim that Causey is legally actually innocent. “There is now-acknowledged law enforcement misconduct involving false confessions,” the writ said, “specifically involving former Det. Hector Polanco, which corroborates Causey’s sworn version of his interrogation.” The attorneys also had new evidence that someone else committed the murder, namely, the first suspect, Kevin Harris, whose 1991 girlfriend said in a deposition that he had called her in the middle of the night after the murder and asked for help moving a car, which turned out to be Byington’s; her account was backed up by a friend, who also gave a deposition.

Working with the DA’s office, the two sides joined together in several filings to the court, which last year vacated Causey’s conviction on two of the grounds and granted him a new trial. But Causey’s lawyers had asked that he be found actually innocent, which is much harder to prove. Judge Eldridge called a hearing to investigate further.

The hearing became a primer on false confessions—and on how Polanco got them. Richard Leo, a professor at the University of San Francisco and one of the world’s foremost experts on the subject, testified that Causey’s confession was “extremely likely a false confession. It had all the characteristics you’d see in a false confession and none of the characteristics you’d see in a reliable confession.” Leo noted that Causey has a low IQ (estimated at 66), making him susceptible to manipulation, and said his case resembled seven others Polanco was involved in (those of Ochoa, Bell, Bowser, Briones, Davis, Osaze-Ediae, and Salazar): the interrogations were long and full of threats (lethal injections, prison rape) and the suspects were fed facts about the crimes. Talking about the APD during this period, Leo testified, “There was clearly a pattern of police-interrogation misconduct leading to provably false confessions, the second worst in the country.” He said the worst department by far was in Chicago, which for years has been called “the false confession capital of the U.S.”

The star witness of Monday’s hearing—the conclusion of which will take place in January, after which Eldridge will make a recommendation on Causey’s case to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals—was Chris Ochoa, who had been threatened by Polanco into falsely confessing to murder back in 1988. Ochoa is 57 now, with graying hair and black glasses. He got his law degree after getting out of prison and today is director of legal affairs for an oil company in New Mexico. His voice often cracked as he recalled Polanco’s interrogation techniques—the yelling, the threats, the slammed fist on the table. Ochoa said that for years, people have asked him why he confessed to something he didn’t do. “I was frazzled,” he testified. “I didn’t know which way was left, which way was right. I just wanted to go home.”

Causey sat quietly the whole day. The only time I saw him physically react to anything was when Ochoa was wrapping up his testimony. “I believe in the system of law,” Ochoa said. “It’s people who mess it up. If there’s a mistake, fix it. These wrongful convictions, there’s a collateral damage that people don’t know about.” Causey was nodding along with Ochoa, his brother in an exclusive club neither ever wanted to join.

Photo Credits: Zuiliani: Ralph Barrera/AS-90-37573-014/Austin American-Statesman Photographic Morgue (AR.2014.039)/Austin History Center/Austin Public Library/Texas; Scanlan: Taylor Johnson/AS-90-38253-010/Austin American-Statesman Photographic Morgue (AR.2014.039)/Austin History Center/Austin Public Library/Texas