Over a prison phone in Huntsville, Ivery Dorsey is rapping. At 6 cents a minute, time is money, but Dorsey doesn’t think he’s wasting his breath. Serving his seventeenth year of a twenty-year sentence for a murder he insists he didn’t commit, the 49-year-old Houstonian—who goes by the moniker Hallow (as in “hallowed be thy name”)—hopes to become a hip-hop artist upon release.

“I’ve always been a dreamer,” Dorsey explains. Before he went to prison, he was recording a mixtape, Almost Famous, produced by Bruce “Grim” Rhodes, who worked on well-known tracks like Lil’ Troy’s “Wanna Be a Baller.” Dorsey regales me with some bars he’s been working on. “The truth is to be sold and not to be told. See that’s the lies that they been selling just to tarnish your soul,” he raps. “We gotta remain on point with the choices we make, it’s so easy to be deceived by the two-headed snake.”

For most of his sentence, there was little chance Dorsey could get out of prison early and launch his career. He rapped as a form of “cell therapy,” to keep himself sane as the chance of release dwindled. Suicide crossed his mind at one point. But now the realization of his dream is starting to feel within reach. His third parole hearing just wrapped, and he’s got his best chance yet of leaving prison, thanks in large part to a small group of unusual champions who helped him prepare for the proceeding. In the spring semester of 2023, three students at Princeton University took an atypical college course: one that examines potential wrongful convictions. Joined by a Georgetown law school student, they began a four-month-long investigation into Dorsey’s case, compiled their findings and interviews into a documentary, and helped Dorsey get a lawyer.

Many in the murder victim’s family maintain Dorsey is guilty, but momentum has built for his case. Now, after nearly two decades of fruitless hope, those students might secure Dorsey’s release. “When I first came here I used to wake up and wonder what I’m doing here,” he said. That aimlessness is gone, as he awaits his parole decision: he has a sense of purpose.

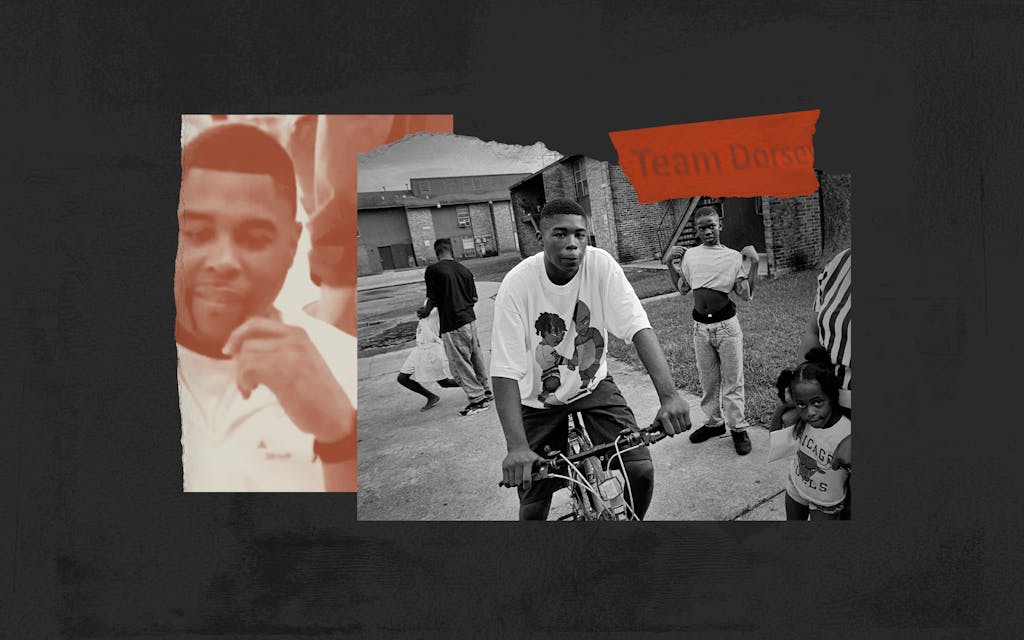

Dorsey grew up in a Houston apartment complex known as “the bricks.” This slice of the South Houston projects was, at the time, “one of America’s most squalid and violent HUD complexes,” according to former Houston Post journalist Bryan Denson, who befriended Dorsey while covering the spike of Black teen gun homicides citywide in the early nineties.

Dorsey grew up playing baseball and was an avid fan of Houston’s burgeoning rap scene. For most of his youth, his dad was absent, and his mom was a drug user. At fifteen, while vacuuming the apartment, he found a yellow carbon copy paper under a couch cushion from an HIV test his mom had taken that came back positive. Dorsey, the de facto man of the house, took care of his sister, ten years his junior.

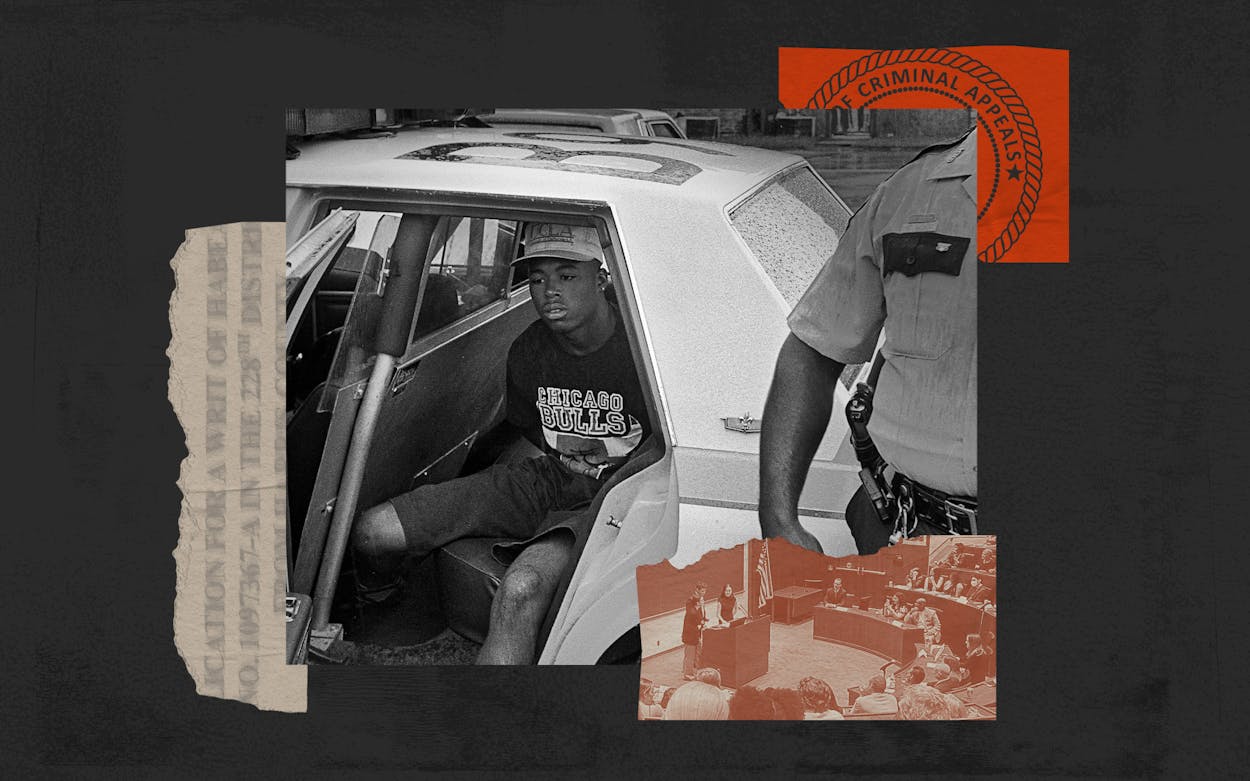

His home life was often violent: in his teens a man broke into his house and began beating his mother, accusing her of stealing drugs from him. Dorsey shot the man, who survived, and he was quickly cleared of charges by a grand jury. It was his first brush with a justice system that would soon enmesh him. At fifteen, Dorsey was arrested and placed on probation for a year by authorities for trying to steal a car. Soon after, he started hustling, selling weed and crack, to make ends meet for his family. “It was the easy way out at the time,” he explained.

When his mom’s health deteriorated, Dorsey dropped out of school as a tenth grader in 1992. His mother passed away shortly thereafter. Dorsey’s sister went off to live with their grandmother, and seventeen-year-old Dorsey started staying with a girl four years his senior who later became the mother to Ivery Jr., his first child. Denson offered him a place to stay in Montrose, but Dorsey feared looking out of place and being profiled in a more well-to-do Houston neighborhood. So he stayed put.

Soon his life would be turned over. On a warm night in July of 1994, a group of armed men holding shotguns and handguns raided a dope house in southeast Houston shortly before midnight and kicked down the door so hard it bent the dead bolt. Inside the house 23-year-old Willie Williams was cutting the hair of a fellow dope dealer, 17-year-old Clifford Tyler. They ran out the back of the house and were clipped as they escaped, but their friend and drug-dealing partner, Charles Monroe, was killed outside the home. In the immediate aftermath, neither Williams nor Tyler could identify the perpetrators, according to police reports. Williams made out only one suspect, whom he clocked as a 20- to 25-year-old Black man but of whom he’d only caught “an image” for a “split second.” Tyler recalled seeing a short and skinny Black male in his thirties but didn’t know who it was.

That was the story for twelve years—until May 2006, when a homicide detective went to Tyler’s house with a photo lineup of six potential suspects. It included Dorsey even though, at the time of the murder, he had been just under twenty and, at six-foot-one, did not meet Tyler’s description of the shooter. The state, though, had connected Dorsey to the crime after police tracked down records indicating Monroe’s cellphone had been used to call Dorsey’s residence shortly after the murder. Tyler, who had gone to middle school with Dorsey, recognized his face in the photo lineup. A couple weeks after the police drop-in, Tyler came forward and said Dorsey was the man who shot him and killed Monroe.

In the decade after the murder, Dorsey had acquired a rap sheet. In 2003, he served seven months in state jail for possession of less than one gram of cocaine, and over the course of about ten years he was intermittently jailed for marijuana possession and weapons charges.

At his trial in December of 2007, Dorsey’s defense stuck to a simple argument: that the testimonies against the defendant were weak. For one, Williams couldn’t definitively identify Dorsey. And Tyler’s testimony, Dorsey’s lawyer contended, was suspect, given the twelve-year time lapse between the murder and his identification. (Eyewitness testimony is notoriously flawed and a leading cause of wrongful convictions.) Dorsey’s attorney provided evidence that Tyler had seen Dorsey four times after the crime was committed—they even spoke once at a flea market later that same year.

The state, in turn, argued that Tyler had stayed silent for more than a decade because he didn’t want to snitch. “I’ve been trying to avoid it. . . . Feeling like I’m doing something wrong when I’m really doing something right,” he testified. Tyler also said that, as he was getting older, he felt worse about lying to his mother about what happened.

Prosecutors also called a second witness: a jailhouse informant who had reportedly heard Dorsey confess to the crime. But, once on the stand, he said he’d been intimidated into testifying by the prosecutor and homicide detective and swore he had never talked to Dorsey about the murder.

It was a potentially embarrassing misstep for the prosecution, but the state directed the jurors to follow the “one-witness rule,” a Texas standard that holds that, as long as a single witness testifies to all elements of an offense and is believed beyond a reasonable doubt, that witness’s testimony can be used to convict a defendant.

After a three-day trial, all twelve jurors found Dorsey guilty.

Dorsey went to prison, and for five years the case was closed. Then in December 2012, Exzavier Stevenson confessed to the murder after receiving a letter from the Innocence Project detailing Dorsey’s alleged crime. Stevenson, who lived on Dorsey’s street growing up and was six years older than him, was serving a sentence for a double murder over a 10 cent dispute at a convenience store. “I’m doing this affidavit because it is what I must do,” Stevenson wrote in his confession. “The right thing is to face up to my actions once again.”

Details from Stevenson’s affidavit as well as information he gave Harris County district attorneys in a subsequent evidentiary interview matched up with known facts of the case. Stevenson explained how he had hit the stash house, kicked down the door, saw one man cutting another’s hair, and saw “a white chubby guy” in the living room. (Monroe was in fact a light-skinned Black man but had the nickname “Whiteboy”). “That alone, if this was the opposite side and he was a police witness, would’ve been enough to send a person away for life,” said Dorsey’s attorney Brian Ehrenberg, a professor at Texas Southern University’s law school who took on the case pro bono. Stevenson also remembered specific characteristics of the house, like the pool table in the front room and three nice cars in the front yard.

Stevenson provided an explanation for why Monroe’s cellphone had been used to call Dorsey. He said that the phone had been taken from the house on the night of the murder and he had given it to Dorsey because “he was really the only person I talked to, that I really knew at the time.” Dorsey then tested the phone by calling his house, he said, but ultimately gave it back to Stevenson. The two men’s explanations differ: Dorsey says he returned it immediately, while Stevenson said that Dorsey returned the phone after police talked to him in the days after the murder.

Armed with the affidavit, Dorsey appealed his conviction. When Stevenson’s affidavit was presented at an August 2020 Harris County evidentiary hearing as part of Dorsey’s appeal, there were some discrepancies in his testimony: for example, whether Stevenson gave the cellphone or sold it to Dorsey; whether he lost the phone or threw it away after Dorsey returned it; his description of Monroe’s wounds; and the number of gunshots that were fired in the house. Prosecutors argued he was copping to a crime to spare his friend. The defense, though, countered that his decision could put him on death row. Dorsey’s defense also argued that Stevenson, who was intellectually disabled with an IQ of 51, could not fabricate this story with detail and maintain a consistent retelling of it.

Nonetheless, the district court ruled the affidavit was insufficient to prove Dorsey’s innocence. Dorsey began to shop his case around, to reporters, innocence nonprofits, and anyone he thought would listen.

In 1988, Marty Tankleff, a twelfth-grader from Long Island, was arrested for the murder of his parents. He was charged for the murder in 1990 and served seventeen years in prison.

His childhood best friend, Marc Howard, investigated the case for his high school newspaper and concluded Tankleff was innocent. Howard went to Yale and became a professor of political science at Georgetown University. While teaching, he also attended law school. Beginning in the early 2000s, he visited Tankleff regularly in prison and published op-eds in the New York Times and Newsday professing his innocence. He helped with Tankleff’s appeals, and in 2007 the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court determined Tankleff was innocent.

Tankleff immediately enrolled in college courses, went to law school, and became a criminal defense attorney in New York. In 2018, he and Howard launched a course at Georgetown called Making an Exoneree, in which students reinvestigate potential wrongful conviction cases for which there is no DNA evidence available.

Since its inception and subsequent expansion to Princeton, the program has been flooded with more than four hundred case inquiries. Students have handled 34 cases and have helped free seven convicts who spent a combined 187 years in prison for crimes they didn’t commit. “We’re not their lawyers,” Howard said, referring to cases the class picks up. “What we do is reinvestigation. If we find that the person is guilty, we move on.”

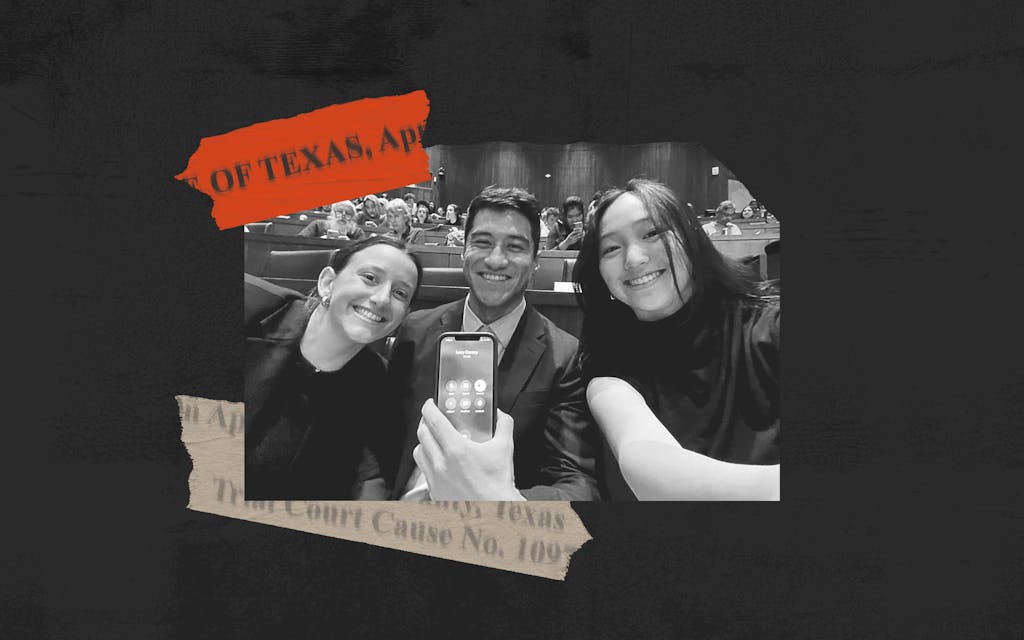

In 2022, Dorsey sent his case to a reporter who in turn forwarded his story to Howard. Three Princeton students—Ben Bograd, Kerrie Liang, and Kennedy Mattes—and Georgetown Law student Kayla Ahmed were intrigued. They began reading all relevant documents of the case—police reports and hundreds of pages of trial transcripts—and then started talking with Dorsey. They flew down to Houston and interviewed friends and others relevant to the case, met Dorsey in Huntsville, and amassed more than 580 signatures on a petition for his release. By the end of the semester their discussions with Dorsey had gone beyond his case. In one call, he taught them how to make prison cheesecake with Sprite, Oreos, cream cheese, powdered milk, and graham crackers. “I consider Ivery to be the big brother I’ve never had,” Mattes said. He thinks of the students, in turn, “like angels.”

Seeking help for Dorsey, Mattes reached out to all Texas-based innocence organizations. Ehrenberg responded. Ehrenberg eventually agreed to assist Dorsey with his parole, and even after three of the students graduated, they helped assemble facts of the case, a psychological evaluation, and letters of support.

One such letter came from DeRoyce Glenn Jackson, the brother of the victim Charles Monroe, who wrote that he was in favor of Dorsey getting parole. “I think very highly of the fact that he took the time to explain his side of the story and most of all I think he’s paid his debts to society,” Jackson wrote. Jackson told me that whether or not Dorsey actually committed the crime was irrelevant to his parole.

Many others in Monroe’s family do not support the effort to free Dorsey. Monroe’s mother, Alice, believes the legal system got it right. “We had prepared ourselves as a family that this was going to have to go back to be retried,” she said. She has forgiven Dorsey, but none of the evidence has convinced her of his innocence. Monroe’s 49-year-old sister, Felicia Richardson, says her brother’s death remains painful. “You try to move forward and then you have something you want to talk to your brother about, and you can’t,” she said. “You have to go talk to a grave.”

“He missed out a whole life. His children never got the chance to hear their father fuss at them, to discipline them,” Richardson continued. “A mother buried her child. And every December. Every July. Every May. . . . Every time you turn around it’s something that you’re wondering, ‘How would life be if he was here?’ ”

Late in 2023, as he awaited his third parole hearing, Dorsey was in good spirits, saying he felt “blessed.” He had been accepted into a six-month Christianity-based program that, if he is granted parole, would help him secure employment. He was spending his days making music on prison-provided tablets. He was also designing sneakers, drawing dozens of futuristic mockups, and in August, he secured pro bono intellectual property representation for his designs.

But he now finds himself in a catch-22. Typically, parole boards view an admission of guilt as a prerequisite for granting early release, according to Northeastern University professor of law and criminal justice Daniel S. Medwed, who wrote a letter of support for Dorsey. This complicates proceedings for those who maintain they didn’t commit the crime they were convicted of. “They can choose either to (1) continue to proclaim their innocence and harm their chance for obtaining parole or (2) they can ‘admit guilt’ to boost the odds of a favorable parole grant, yet by doing so reduce the possibility that they will ever be able to prove their innocence through litigation because the contents of their parole file may be readily accessible to prosecutors,” Medwed wrote.

For Dorsey, the decision is easy. He’d rather die with his truth than live free on the knees of insincere penance. This could pay dividends if, in the future, he chooses to pursue actual innocence, a legal verdict necessary to receive compensation for wrongful time spent behind bars. But that’s a long shot. Regardless, when he gets out of jail, either this year or 2026, when his sentence is complete, it’ll be on his own terms, to his own tune.

Update, January 30, 2024: On Friday, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles approved Ivery Dorsey’s release after his third hearing. “When they first told me the news I couldn’t do nothing but break down and cry and just thank Jesus over and over because it’s been a long time,” he said.

Dorsey will soon be going home at the age of 49, but first he must complete a reentry class. And after that, a new fight begins. “I want to be exonerated,” he told me. “I want my name cleared.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Houston