This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Room H-128 of the U.S. Capitol is not on the tour. Visitors and guides never see this obscure room, one floor below the House chamber in a remote corner of the building. Neither, for that matter, do most members of the House. It has been 25 years now since the little room has been a part of American history, 25 years since Speaker Sam Rayburn closed the door for the last time and went home to Texas to die.

On December 8 the Democratic members of the House will choose another Texan as their new Speaker. The successor to the retiring Tip O’Neill is certain to be Jim Wright of Fort Worth, and his political heritage was shaped behind the door to Room H-128. In Rayburn’s day, the room was the meeting place of the small group of Capitol Hill insiders known as the Board of Education. Late in the afternoon, after the House had adjourned for the day, they would gather to talk politics with the Speaker over bourbon and branch water. Vice President Harry Truman was there on an April afternoon in 1945 when a phone call summoned him to the White House for the news of Franklin Roosevelt’s death. Rayburn’s protégé, a young congressman named Lyndon Johnson, learned the inner workings of the House in this sanctuary. So, years later, did young Jim Wright.

The Board of Education did not survive Sam Rayburn, nor did the kind of politics it represented. Rayburn’s House operated according to his celebrated maxim, “In order to get along, you have to go along.” In his day the phrase had the status of revealed truth; today it has fallen into disrepute. It is synonymous with the excesses of good ol’ boy politics: logrolling and pork barrels and passive politicians who see, hear, and speak no evil while they await their turn. As Rayburn’s philosophy has fallen into decline, so has the office he once held. O’Neill had the image of a back-room politico who was out of touch with the country. He lost effective control of the House in the early years of the Reagan presidency; when he regained it in 1983, he did little with it.

Now it is Jim Wright’s turn. His ascension is an enormously significant event for Texas. “Ever since I’ve been in Washington,” says Congressman Charles Wilson of Lufkin, who arrived in 1972, “it’s been open season on Texas. Now hunting season is closed.” For the country, the Wright House will be a far different place than the O’Neill House. Because the Democrats have retaken control of the Senate, Wright does not bear O’Neill’s burden of being the party’s front line of defense against Ronald Reagan. He is free to set his own course. What will that course be? How did he come to be elected Speaker of the House? What sort of politician is Jim Wright? These are crucial questions for the House, the Democratic party, and the nation. Their answers lie behind the locked door to Room H-128, and Wright’s success as Speaker will ultimately depend upon whether he can restore a measure of respect to the kind of politics that used to be practiced there.

Mr. Inside

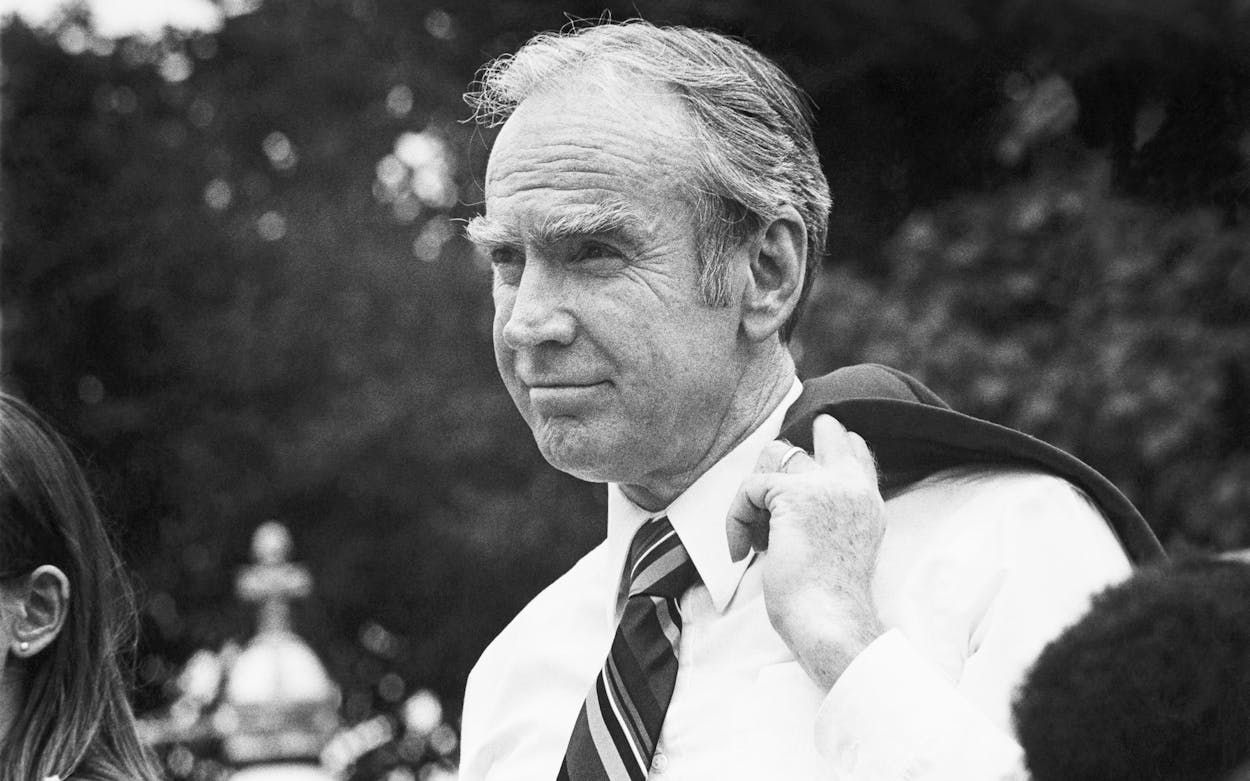

In describing Jim Wright, everybody starts with the eyebrows. They are a cartoonist’s dream, a personal characteristic as distinct as Nixon’s nose or Carter’s grin. Thick and bushy, they sprout out from his forehead like mutant moustaches.

The eyebrows, though, are false advertisements. They are obvious; everything else about Wright is hidden. After 32 years in the House Wright is still unknown to most of political Washington. He is even less well known back in Texas. This past summer there was a party at the River Oaks Country Club in Houston to introduce to the Houston establishment the man who had been majority leader of the House for ten years.

Wright is the essence of a House insider. His closest friends are staffers and former staffers. His wife is a former staffer. He is a student of the other 434 House members. He knows how they campaigned and why they won, what they want and how he can help them get it. If they are Democrats, he has probably contributed money to them (he has a personal political action committee that doled out more than $300,000 to House candidates this year) and campaigned for them in their districts. He used to keep a map on his wall with pins representing every congressional district he had campaigned in; now he says he has lost track, but it’s well over half.

His thoroughness was evident in 1976, when he was running for majority leader. All first-time Democratic congressional candidates were invited to Washington for a campaign seminar. Wright’s chief rival, Phillip Burton of California, held a cocktail party for the aspiring freshmen. Wright met with them in his office, one to one.

There is a reason why Jim Wright is such a consummate insider: he doesn’t really fit into the political world outside the House. Wright will be the last Speaker who came of age during the Great Depression. In all likelihood, he will be the last one who did not graduate from college (he was at the University of Texas when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor; when the war ended, he returned to his hometown of Weatherford and began running for the Legislature). He is out of phase with modern politics. Ideological labels like liberal and conservative offend him. “Adjectives don’t just define,” he complains. “They confine.” He resents the importance of TV, and he is frustrated by its superficiality. “Substance is my thing, not image,” Wright says, but TV projects image, not substance. He has never mastered the art of dealing with the Washington press corps and gloats that not one Washington-based reporter predicted that he would win the majority leader’s race.

He still prefers to do things for himself that other Washington politicians turned over to experts and image-makers years ago. When he had to cancel a meeting with a South American leader, Wright shunned the standard practice of asking the State Department to draft a letter of regret in Spanish and wrote one himself—in Spanish, which he learned in the sixties by attending night school at the Foreign Service Institute. He has been known to drive campaign consultants batty by trying to write his own material. Wright still hands out copies of the newspaper ad he composed 32 years ago, which helped him win his first congressional race. It was a 27-paragraph open letter to Fort Worth’s political kingmaker, Amon Carter, whose newspaper had shut Wright out of its news columns and endorsed his opponent. A Star-Telegram editorial had charged that Wright had kept his positions on issues well concealed. “Let’s tell the truth, Mr. Carter,” Wright wrote. “YOU and your personal newspaper have kept them well concealed.”

Wright is acknowledged to be the finest debater and orator in the House. But even this talent is vestigial, serving to underscore his estrangement from the media age. Wright’s style of oratory is better suited to the stump than the studio. It is full of images and metaphors and literary allusions. In the televised sessions from the House floor, younger, made-for-TV politicians deliver their vapid speeches straight into the camera. Their gazes never waver. When Wright speaks, he constantly looks left and right, his hands gesticulating, his face intense. The words are elegant, but on TV the elegance is lost. He looks like a country preacher chastising sinners.

Jim Wright’s politics are out of style, too. He’s drawn to the center in an age of extremes, given to bridge-building in an age of partisanship. He spent most of his career in the House on the Public Works Committee, and he has an instinctive faith in the kind of big government projects that are regarded as boondoggles today. Along with the GI bill, the civil rights acts, and Medicare, the interstate highway system is high on Wright’s list of the few achievements of Congress since World War II that have really improved the quality of life in America. He’s right, of course, but not many politicians would have thought to include it.

In 1981, when Ronald Reagan set out to cut the federal budget, Jim Wright drew his own line in the dirt not at rescuing social welfare programs but at saving the synthetic fuels corporation. The program was an expensive subsidy that enabled big energy companies to make synfuels at a price competitive with oil, and it was notorious for waste and mismanagement. Wright found practically no support for synfuels, from liberals or conservatives, Republicans or Democrats, and the program was dismantled. Today, with oil at $15 a barrel, almost every profile of Wright by a Washington reporter second-guesses his support for synfuels. Wright still believes that in the long run the synthetic fuels program was as essential to the national security as the Star Wars project. But in the eighties, the long run, like Wright himself, is out of fashion.

In a way, he always has been. He was a liberal in the conservative Texas of the fifties, a hawk among doves in the sixties, and a conservative elected to a leadership position by a liberal, reform-minded Democratic caucus in the seventies, and now is an unrepentant defender of government projects in the tightfisted eighties. Jim Wright has had as strange a career as anyone ever to ascend to the office of Speaker.

Man of the House

When Jim Wright went to Washington in 1955, the U.S. Senate, not the House of Representatives, was his ultimate destination. Intensely ambitious, he was not suited to the long years of waiting that were a prerequisite to power in the House. In 1961 he saw his big chance. One year earlier, the Texas Legislature had changed state election law so that Senator Lyndon Johnson could hedge his bets. Johnson was John Kennedy’s running mate that year, but just in case the national ticket lost, he was allowed to seek reelection as senator at the same time. When Kennedy won, Johnson resigned his seat. The special election that followed was one of the wildest episodes in Texas political history. It also proved to be one of the most significant.

Wright was the first person to announce for the race. His idea was to scare off other opponents. The strategy didn’t quite work. Seventy-one contenders followed him into the fray. Among them were William Blakley, an extreme conservative Democrat who had been appointed to fill the vacant seat until the election, and a Republican government professor from Midwestern University in Wichita Falls named John Tower.

At first Wright’s chances of making the runoff appeared excellent, and he stood to receive most of the state’s sizable liberal vote. He had an almost spotless liberal record. In 1947 he had been the most liberal member of the first postwar Legislature. He voted to let women serve on juries, spoke against the poll tax, tried to tax oil—and was defeated for reelection. Elected to Congress in 1954, he became the foremost liberal in the Texas delegation, a designation for which there was scant competition. But in counting on support from Texas liberals, Wright failed to reckon with their suicidal purity. In 1959 he had voted for a labor reform known as the Landrum-Griffin Act, which mandated elections for union officials. When Wright announced for the Senate, Texas labor leaders decided to punish him. They recruited Maury Maverick, Jr., of San Antonio to take votes away from Wright. Meanwhile, Henry B. Gonzalez, then a state senator from San Antonio, had joined the growing list of liberal candidates.

Wright made one last play to avoid the fracture. The first vote at the AFL-CIO convention would be whether labor should make any endorsement. Wright tried to form an alliance with Gonzalez to keep labor neutral. Gonzalez, however, insisted on trying for labor’s backing, and his forces joined with Maverick’s to vote for making an endorsement. In the end labor sided with Maverick, and the liberals were hopelessly split.

The Republicans made no such mistake: John Tower was their only entry in the nonpartisan race. On election night Tower led the field by 137,000 votes. Wright finished third, a scant 20,000 votes behind Blakley. Maverick got the labor vote but ran a poor fifth. Gonzalez carried the minorities but ran sixth. In the runoff the liberals, having fouled their own nest, then set about to foul the conservative Democrats’. They voted for Tower, who beat Blakley by 11,000 votes. No one doubts that had Wright reached the runoff, he would have beaten Tower with ease. Instead, Texas got a Republican senator.

The liberals learned nothing from the race. When Tower ran for reelection in 1966, they spurned conservative Democrat Waggoner Carr and provided Tower with his margin of victory. But Jim Wright learned a lot. He learned that his future was in the House, not in the Senate. And he learned that he did not belong in the liberal wing of the Democratic party.

Heir to the Throne

The sixties were dreary years for Wright. People who have tasted defeat are the exception in the political arena, and Wright had partaken of the bitter potion twice. His Senate ambitions were thwarted, and his role in Congress was minuscule. The liberal reputation of his youth had prompted the conservative Texas delegation to keep him off the major committees. Instead, he was sent to Public Works, which hands out money for dams, highways, and federal buildings.

There was nothing to do except collect seniority and wait. Colleagues from those years remember him as frustrated and cautious. He brooded over his first defeat as well as the second. His politics changed as much as his personality. “I had made the mistake of thinking I could get way out ahead of the public,” Wright recalls. “I felt invincible. I didn’t get beat because I was a liberal; I got beat because I was too outspoken. Nobody loves a crusader.”

No one was going to accuse him of being a crusader again. He became just another pork barrel congressman. He won authorization for a barge canal for the Trinity River (it was never funded). He took advantage of Dallas’ right-wing reputation to make Fort Worth the regional center for federal office buildings. In 1966 he made an exploratory pass at getting into the Senate race against Tower, but although his voting record was getting steadily more conservative—he had even opposed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964—he found that the money men back in Texas still didn’t trust him. More waiting, more caution. He backed Lyndon Johnson and then Richard Nixon on the Vietnam War. He voted to require food stamp recipients to work. He voted for school prayer and against busing.

Only in the area of economics did Wright remain an old-fashioned liberal. He had, after all, been a child of the Great Depression. It had changed his life, taken him out of Weatherford as a boy and uprooted him to Dallas. Wright’s grandfather had lost his job—his employer had fired everyone with more than 20 years of service in order to avoid having to pay an annuity that accrued after 25 years—and was about to lose his house. There was no Social Security. Wright’s family moved in with his grandparents and paid enough rent to stave off foreclosure. It was not the sort of experience one cast off lightly.

Because of his record on social issues and the Vietnam War, the liberal Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) consistently rated his voting record below 50 per cent. Because of his record on economic issues, so did the conservative National Association of Business. That was a rare combination outside the Texas delegation, but a familiar one inside it. Unlike other conservative Democrats, Texans had no philosophical objection to government spending, so long as enough money found its way to Texas—and enough Texans were in positions of influence to see that it did. Jim Wright had joined the Texas mainstream.

More years went by. Waiting was not paying off. In 1975 Wright marked his twentieth anniversary in the House, and he still was not a committee chairman. He did hold the post of deputy whip, a foot soldier in the Democratic leadership, mainly because he served as a bridge between Northern and Southern Democrats. At last, in 1976, the chairman of Public Works announced his retirement, and Wright stood on the verge of a chairmanship. But he was destined for a different gavel.

Another retirement was occurring that year: House Speaker Carl Albert’s. Majority leader Tip O’Neill was certain to replace Albert. The race to fill O’Neill’s old job, however, was a different matter. Majority whip John McFall wanted to move up, but he had been tarnished by his association with a controversial South Korean lobbyist. The other announced contenders were Phillip Burton of California and Richard Bolling of Missouri. On the surface they were a formidable pair. Burton was the leader of the liberals and a brilliant tactician. Bolling was an intellectual, a student of how the House worked, and a voluble proponent of reforms to make it work better.

Wright did not have a legislative record to match Burton’s or Bolling’s. His one moment in the limelight had come in 1973, when he had led a successful floor fight against an attempt to divert highway trust funds for mass transit. But if he wasn’t a legislative giant, he was a student of the House, and he knew that Burton and Bolling had enemies. Burton had been an instigator of the 1974 reforms that had diluted the seniority system. If the young liberals adored him for it, the older members who had been waiting their turns were not so enamored. As for Bolling, the quality that was regarded by some as intelligence was regarded by others—especially Southerners—as arrogance.

Wright told trusted friends that he thought he saw an opening. Without exception, they counseled against his getting in the race. He was too late, they said. He was too conservative for the liberal-dominated Democratic caucus. Try for whip, they advised. But he understood that the voting system in the Democratic caucus would work to his advantage. The first secret ballot would eliminate only the candidate with the lowest number of votes. Another would fall on the second ballot, and another on the third, until only one was left. He knew that he wouldn’t be the first choice of very many of his colleagues—but he would be the second choice of many more.

On the first ballot, as expected, McFall fell: Burton 106, Bolling 88, Wright 77, McFall 31. Southerners and Texans made up Wright’s base. Fifteen minutes later the Democratic caucus voted again. Burton 107, Wright 95, Bolling 93. Now it was down to Burton and Wright, and a rumor swept through the caucus: Burton had told some of his backers to vote for Wright, whom he thought would be easier to beat than Bolling. No one knows where the rumor started or whether it was true (Wright says emphatically that it wasn’t), but some of Bolling’s lieutenants were outraged. On the third ballot Wright won by a single vote, 148–147. Burton, the tactical master, was so shocked that he failed to ask for a recount. After 22 years, Jim Wright had stopped waiting.

The Final Step

It is obvious now that the 1986 Speaker’s race was really decided when Wright was elected majority leader in 1976. But it was not at all obvious then. In its 1978 profile of Wright, the Almanac of American Politics said, “Part of his appeal for his present post is the argument that there was need for a moderate counterweight to liberal Speaker O’Neill; that doesn’t wash if Wright runs for Speaker himself. . . . If a speakership race were held today, he would probably lose to Burton or Bolling.”

Wright’s position remained vulnerable through the early Reagan years. The low point came in 1981, after he had intervened to assure plum committee assignments for two young Democrats from Texas, Phil Gramm and Kent Hance. Relying on their pledges to be loyal to the Democratic leadership, Wright saw that Gramm got a seat on the Budget Committee and Hance got a seat on Ways and Means. The appointments backfired horribly. Gramm promptly became a cosponsor of Reagan’s budget cuts, while Hance promptly became a cosponsor of Reagan’s tax cut. The Republican-conservative Democrat alliance overwhelmed the remaining Democrats, and O’Neill lost effective control of the House. To some Democrats, Wright was to blame.

But Bolling retired in 1982, and Burton died in 1983. The Republicans lost ground in the 1982 elections, allowing O’Neill to regain control. The opposition to Wright was without a leader or at issue. Meanwhile, Wright doused liberal suspicions by remaining unfalteringly loyal to O’Neill and opposed to Reagan. (The loyalty continues: in the face of ample evidence to the contrary, Wright ranks O’Neill as “a great Speaker.”) As word began to circulate that O’Neill did not intend to serve many more years, Wright’s voting record moved slightly to the left. His ADA rating in 1982 climbed above 50 per cent for the first time since the fateful Senate race of 1961. At the same time, he continued to do the little things that count so much more than voting records or legislative achievements when the time comes to pick a Speaker: handing out campaign contributions, making campaign appearances, doing little favors on the floor. He used his position to court the younger House members by tapping them to make speeches and get vote counts. When O’Neill announced in 1984 that he would serve only one more term, Wright made a preemptive strike by revealing that he had pledges of support for Speaker from 184 of 267 Democrats.

The last potential challenger to Wright was the powerful chairman of Ways and Means, Dan Rostenkowski of Illinois. Wright could hardly have asked for a better opponent. (In an unflattering article about Wright last spring in the neoliberal journal, the Washington Monthly, Rostenkowski is called “as much of an old-style hack as Wright.”) As one of the principal architects of the 1986 tax reform law, Rostenkowski might have been swept into the Speaker’s office on a tide of adulation over the law. The tide, and Rostenkowski’s candidacy, failed to rise.

One reason that Wright is in such good shape on the eve of the December 8 election is that the House is ready for a change. O’Neill had enormous personal popularity in the House, at least among Democrats, and in official Washington. But he was too easy a target for Republicans (a freshman Republican said in 1981, “He’s just like the federal budget: fat, bloated, and out of control”).

Every faction in the House has a reason to want a new Speaker. This is because the speakership is a strange office with many roles, most neglected by O’Neill. The Speaker is an engineer who must make the Rube Goldberg contraption that is the House run smoothly. But younger members protest that the House functioned ponderously under O’Neill and that its traditional three-day work week was too short. (“There’s not a single member of the House who doesn’t believe it can work better,” says Charles Stenholm of Stamford.) The Speaker is a national figure who should understand the mood of the country apart from politics. But O’Neill shut the Republicans out; he never negotiated for their votes. The Speaker is still a regional representative, and Wright’s Texas roots are a comfort to conservative Democrats, who want their party to move closer to the center. For most of O’Neill’s tenure, conservative Democrats were blocked from major committee assignments; only after Stenholm threatened to challenge O’Neill in 1984 did conservatives get more consideration.

Finally, the Speaker is a leader of his party. This was O’Neill’s strongest suit. After losing the budget and tax cut battles in 1981, O’Neill was able to hold the Democrats in line against the Reagan revolution and wait it out. Yet even House liberals are not entirely happy with his passive opposition to Reagan. The Speaker failed to promote a Democratic agenda or even provide clear Democratic alternatives to Reagan programs. “Tip is not a man who is interested in substance,” John Dingell of Michigan, the chairman of the Energy and Commerce Committee, said in the Congressional Quarterly this year. O’Neill preferred to play defense, taking the British view that the duty of the loyal opposition is to oppose. As the Reagan era enters its sunset years, many House Democrats are hungry for legislative initiatives from the Speaker’s office that can define what the party stands for.

Late in the summer, Wright gave the House an indication of how things could work with a different kind of Speaker. The Reagan administration was making headlines with its concern about the drug problem. At the same time, drug legislation in the House was bogged down in committees with overlapping jurisdictions. With O’Neill’s approval, Wright decided to use the drug issue as a showcase for his leadership. (It proved to be a sad and ironic choice: Wright’s daughter and son-in-law were arrested in October under drug-related circumstances.) He gave committee chairmen tight schedules to complete their hearings. Taking the various committee proposals, Wright assembled an omnibus bill and quickly moved it onto the floor. He refrained from using House rules to block the consideration of amendments sought by conservatives—a tactic O’Neill often employed. The result: a tough bill that passed by a 392–16 vote, the kind of bipartisan margin that has been rarely seen on major issues during the Reagan years. The Wright era had begun.

The Lesson of Room H-128

A quarter of a century has passed since the House last had a Speaker from Texas. Neither the House nor American politics bears much resemblance to the things Sam Rayburn knew. But Rayburn would have no trouble recognizing Jim Wright. “The next Speaker of the House is the last triumphant gasp of the go-along-to-get-along Democrats,” the New Republic wrote a year ago. After all these years, Wright still has more in common with Rayburn than with any member of the current House.

One October afternoon, Wright settled back en route to another fundraiser and talked about Rayburn: “Everybody trusted him. He never asked you to do anything that could cause you political trouble. During my ’61 Senate race, he was trying to enlarge the Rules Committee. It was a big fight, very close, but he didn’t ask me to come back from Texas for the vote. I came anyway, and he told everybody, ‘I knew Jim would come back.’ ”

The similarities between the two Texas Speakers are striking. Both came to the House as liberals and moved to the center. Both faced a turning point in their sixth year (for Rayburn, the Democrats lost the House; for Wright, he lost the Senate race) and entered a long, dark waiting period. Rayburn was wedded to the House, even more than Wright. Like Wright, he found it hard to adjust to TV. (When President Eisenhower went on television to plug the Taft-Hartley labor bill, Rayburn gave the Democratic rebuttal on radio.) Rayburn was a partisan Democrat, but he helped pass a Republican president’s program and ran a bipartisan House, just as Wright did on the drug bill.

“I would very much like to have a relationship with the White House like Sam Rayburn had,” Wright says, “but I don’t see any possibility of that happening. Conversations with Ronald Reagan are not a two-way street.” Reagan treats House Democrats in much the same way as O’Neill has treated House Republicans: he doesn’t believe in negotiating.

In 1982 Wright went to the White House to talk about the budget. “I tried to talk in terms the president would understand,” Wright says. “I said I foresaw trouble for our national defense in the future. We’ll need highly skilled people to operate sophisticated weapons, but we’re making it more difficult for two million Americans to go to college.

“I lost him there. ‘Jim,’ he said, ‘I hear that a lot of these kids are taking our money and investing it in CDs.’ ”

Wright shook his head. “Well, what do you say?”

Wright will try to give the House some bargaining power by seizing the initiative. “I’d like to single out four or five major objectives in a year and marshal the House to them,” he says. “We can’t be passive.” Wright wants to do something about the budget deficit, the trade deficit, energy, and economic growth.

Fine—but what? For the moment, Jim Wright is not saying. He stopped being the kind of politician who had answers in 1961 and began being the kind of politician who lets others find them. Only then do his skills come into play. In Sam Rayburn’s time, this was no burden. Today it is. Consequently Jim Wright will have to endure the suspicion in the press and in the ideological left wing of his own party that he is, after all, just another back-room operator, a Tip O’Neill in Texas clothing, but without O’Neill’s Irish charm or moral compass.

For a hint about what Wright might do in the future—and how he might do it—look to his past. He has consistently supported laws that shore up lagging U.S. industries. He favored giving U.S. flagships a guaranteed share of oil import traffic. He supported a requirement that foreign cars be built with some U.S. parts and labor. He backed the Chrysler loan guarantee. None of this is compatible with Reagan’s free-market philosophy. But Wright has found ways to bring together the unlikeliest of bedfellows. In 1978 he passed an amendment that resolved a long and acrimonious dispute over whether Southwest Airlines could continue to use Love Field in Dallas. To preserve the status of DFW Airport as the primary interstate terminal—something crucial to Fort Worth—the Wright amendment restricts flights departing from Love Field to destinations only in Texas and the four adjacent states. It’s not perfect, but in classic conservative Democratic style it gets the problem out of the way and lets business go on.

That’s the way Sam Rayburn did things. But in his time, the Speaker could run the House with the compliance of a few key chairmen. Today reforms have undercut the absolute power of the chairmen, who can be removed by a vote of the Democratic caucus, regardless of seniority. With the decline of the seniority system, the custom that young members have to wait their turn is abrogated. Moreover, power is much more diffused. As the chairmen become weakened, power is inherited by dozens of subcommittee chairmen, many of whom have more power over legislation than the chairmen do.

Still, the modern Speaker is not as weak as he might appear. In the old days, the Speaker had no control over committee assignments; vacancies were filled by the majority party’s members on Ways and Means. Today that power belongs to Steering and Policy, which is controlled by the leadership. The House may operate in a more democratic fashion, but democracy should not be confused with power. Indeed, the diffusion of power can work to a Speaker’s advantage: the smaller the baronies, the harder it is to challenge the prince. Ultimately, a Speaker’s authority depends on the same thing it always has: the force of his own personality.

And that brings us back to Room H-128. One afternoon in January, after the House has adjourned, James C. Wright of Texas, third in the line of succession for the presidency of the United States, will unlock the door and reconvene the Board of Education. Then he will set about the task on which his success as Speaker depends. He must resurrect the values implicit in the idea of going along to get along: that pragmatism and compromise are preferable to the ideology and confrontation that have dominated American politics since Sam Rayburn died.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fort Worth