That’s All for Now, Folks

Ben Rowen, 5:31 p.m.

Thanks for following along today, folks. We’ll be back tomorrow with Day Two coverage.

Recapping Day One

Christopher Hooks, 5:24 p.m.

The squabbling over rules of evidence proved too much. The court adjourned about an hour earlier than expected so the teams of well-heeled lawyers could argue more in private.

This was the first day of what may be a marathon trial, and a lot of today—resolving pretrial motions, debates about evidentiary rules—was admittedly quite dull and probably not all that indicative of the eventual result. But we do know a few more things now than we did at the start of the day.

First, Paxton’s attempts to do an end run around the trial and throw out the charges before they could be presented fell flat. None came close to winning a majority vote to dismiss, though a few motions on specific charges had enough votes to give reason to doubt that Paxton can be convicted on them later on. (To convict on the sixteen charges, there will need to be a two-thirds vote, versus the simple majority vote to allow their consideration.)

Second, Dan Patrick gives every sign of wanting to handle this straight, as he has continued to do since the House impeached Paxton in the spring. That itself is bad news for the attorney general. The longer this goes on, and the more seriously the Senate takes it, the more damage this is likely to do to Paxton’s standing and reputation.

Third, the legal teams are pursuing very different strategies. Paxton’s top attorney is high-powered trial lawyer Tony Buzbee, who gave a bombastic opening speech that sought to, well, put the whole damn court on trial. That may well pay off, but senators like to be talked to in a particular kind of way. The prosecution has its own high-powered lawyers. But the team is led by lawmakers, and they know how to communicate to other lawmakers. (Only state representative Andrew Murr spoke today, to give the opening statement, but many of the other House impeachment managers are good lawyers and good communicators, and are respected by the Senate.)

Two more small things that should worry Paxton. The Capitol was packed with local TV-news crews today—each one a much more formidable force than all the writers in the building put together. Today might have been slow, but TV audiences love a courtroom drama, and this trial is going to get a lot of airtime before it’s over. In terms of the battle for public opinion, that’s not great for Paxton.

Relatedly, it would have been a tremendous thing for his defenders to see a few hundred conservative activists pack the gallery today to back Paxton—as a show of force. Ideally for his side, they’d be here every day. But not many showed up. The best scenario for Paxton is one in which normal people are tuned out and the base is fired up. At the Capitol today, at least, there was some reason to believe the opposite was the case.

The Elephant Not in the Room

Mimi Swartz, 5:11 p.m.

As proceedings conclude on day one, I’m hearing a lot of buzz about that empty seat at the defense table: the AG who is MIA. The whole Senate has to sit there while Buzbee and Hardin go at it. Even Paxton’s long-suffering wife—who might get a plotline on The Good Wife, it if were still on—is there. But Ken has left the building.

One lawyer friend has suggested that Paxton’s absence is a Trumpian move, making the proceedings look so meaningless that he doesn’t even have to show up. Here’s how that legal expert put it: “Trump acted like impeachment was so frivolous it was beneath him, but I would never have allowed it. You would want him to smile and wave at breaks. You want him to look aggrieved. You want his wife to comfort him. He just looks like a cad. It’s the classic scenario in which politician guy confesses and wife has to stand there; she has to stand there, and he is gone.”

A Brief Look Outside the Capitol

Dan Solomon, 5:05 p.m.

The Paxton trial is the most interesting thing to happen in the Texas Capitol since Wendy Davis donned her pink sneakers during her abortion filibuster ten years ago. Throughout the summer, every lawyer I talked with about the impeachment was salivating at the chance to see the biggest names in the Texas legal profession—Tony Buzbee, Dick DeGuerin, Rusty Hardin—face off in the novel courtroom that is the Texas Senate, with unusual rules and an incredibly high-profile jury. They would talk about it like they were awaiting the Super Bowl of Texas lawyering, giddy at the prospect of seeing these attorneys sling motions and make arguments in a case that, by its nature, couldn’t end with an undisclosed settlement and a quick press release.

State politics don’t always attract the same attention as national politics, though. Wherever that enthusiasm is now, it’s not visible around Austin. The ticketing system set up by the Senate to manage the in-person crowd proved unnecessary today—one can just walk up and claim one of the numerous empty seats—and the televisions of a handful various Capitol-area bars I stopped by, which on an election night would be tuned to cable news for an audience of anxious, hollering political junkies, are showing ESPN talking heads or the U.S. Open. This is somewhat curious. On the one hand: this is the first day of a week-long affair happening in the state Senate chamber on a Tuesday afternoon. On the other: we live in an era during which the line between politics and entertainment is increasingly blurry. U.S. House committee hearings are prime-time appointment television and politicians from Beto O’Rourke to Donald Trump hold rallies that attract crowds like a Phish concert.

As Paxton’s defenders have argued, much of what’s been alleged in the impeachment has been public knowledge for years, and voters have declined to hold those claims against him in election after election. Polling suggests, however, that the issue is less that voters have forgiven or disbelieve the allegations and more that they just haven’t been paying much attention. Today, at least, the early signs point to the impeachment being no more of a flash point than any of the whistleblower complaints, indictments, or court filings that preceded it.

Another Reminder That This Is Not a Criminal Trial

Christopher Hooks, 4:58 p.m.

We’ve hit our first significant stumbling block, with the testimony of Paxton’s former first assistant AG Jeff Mateer on pause while the legal teams approach the bench to resolve a debate about the use of evidence. The prosecutors thought a document had been cleared for use at the trial: the defendant’s legal team objected. They’re all in a big scrum at the front right now, and it looks like it does when the Texas House resolves a point of order. Dan Patrick has adjourned the trial for the day as the issue is resolved.

According to a senior source somewhat familiar with the proceedings (some friendly lawyers sitting next to me in the gallery) this kind of thing—I’m skipping over the details—is the kind of thing that would be pretty easily resolved in a normal court or that an experienced judge might have resolved beforehand. But this isn’t a normal court, and Patrick is not a judge. It’s a trial-ish with some elements of a criminal trial and some elements of a civil trial, and at the end of the day it may not be a trial at all—it’s a meeting of the Senate with an unusual purpose and special rules.

So there may be a lot of moments like this—pretty dull moments, where Patrick, with the advice of actual lawyers behind him, tries to work through procedural issues. There’s not a lot of precedent to rely on—this is the first impeachment the Senate has handled in a half century and the first of a high political official in a century. By necessity, they’re going to have to make a lot of this stuff up as it goes along.

While Patrick is taking his time with this one, though, it has seemed notable that Patrick has felt comfortable dismissing a lot of Buzbee’s objections quickly. Buzbee has argued that much of Mateer’s testimony is hearsay—and that Mateer’s discussions with Paxton are covered by attorney-client privilege. (Paxton was not Mateer’s client, of course—Mateer was an employee of the State of Texas.) Patrick may have given these motions all the consideration they deserved—but he dispensed with them quickly.

How Rusty Hardin Is Prosecuting the Case

Mimi Swartz, 4:46 p.m.

Rusty Hardin’s prosecution is not subtle. He’s taking great pains to establish that Jeff Mateer, one of the whistleblowers, who is currently on the stand, is far to the right. He had a question about where Mateer would rank himself on a conservative scale of one to ten; “ten,” Mateer replied, denying for good measure that he was a Republican in Name Only. Hardin also tried to drive home the fact that Mateer couldn’t get a job as a federal judge because of his right-wing stances on LGBTQ issues and has highlighted Mateer’s Federalist Society membership, a badge of honor on the right.

At one point, Hardin led Mateer to explain his values as a lawyer in the attorney general’s office. Mateer said he recruited lawyers there who excelled at the three c‘s: calling, character, and competence, in that order. The “calling” in this case was advancing right-wing causes, such as restricting access to abortion.

The whole notion Hardin is trying to establish is that there are guys on the far right who are critical of Paxton whom Republican senators can go along with. Don’t look for anyone testifying to their Bush-era bona fides. Those folks are useless here.

The First Witness

Michael Hardy, 4:04 p.m.

The first witness for the House impeachment managers is Jeff Mateer, a former first assistant attorney general of Texas and one of the eight whistleblowers who accused Paxton of accepting a bribe from Nate Paul, but not one of the four who sued him. Mateer has impeccable conservative credentials—he currently serves as chief legal officer of the right-wing Plano-based First Liberty Institute, which defends religious freedom. On the stand, Mateer has denied being a Republican in Name Only (RINO), describing himself as “far to the right of center” politically. In 2018 Donald Trump nominated Mateer for a U.S. district judgeship, but he withdrew following controversy over anti-transgender remarks he had made.

We Now Know What the Defense Will Be

Mimi Swartz, 3:28 p.m.

Okay, well, now we know, essentially, what the defense will be, according to one of Paxton’s attorneys, Tony Buzbee: the whistleblowers acted improperly, the press has told lie after lie after lie, and the poor lawyers for Paxton have been burdened by Dan Patrick’s gag order, which forbids them from responding to any of the terrible, horrible, no good very bad accusations against the duly elected attorney general of the state of Texas. To quote the extremely well-dressed, well-tanned Buzbee, “He did nuthin’ wrong. Nu-thin’.”

Buzbee, donning a white shirt and canary-yellow tie, posed a little bit of sartorial dissonance to the down-home Paxtons, who, he basically said, lived in a dinky house and had to go to Home Depot themselves to upgrade their home. (The suggestion being that, if Nate Paul had paid for their repairs as alleged, their house might look more like . . . Buzbee’s manse back in River Oaks.) Mostly Buzbee stuck to his earlier accusations that Paxton, who has defeated at the ballot box, in no particular order, everyone from Dan Branch to Eva Guzman—oh, and Louie Gohmert—is the victim of a vicious political plot by elites.

Buzbee also attacked the whistleblowers as whiners, and carpers, and ungrateful subordinates—who never went directly to their boss, Paxton, to complain about his actions. (There is evidence, released by the House managers, that they warned him to stay away from Paul frequently and that, when they asked for a meeting, he was out of town or otherwise occupied.)

Dan Cogdell, who can be pretty laconic in person, was far more animated and a bit more intimate with the crowd, invoking his dead father and his sick wife, who told him, “No, you go on to that trial to defend Ken Paxton. Because . . . democracy is at stake.” (“Is Cogdell going to start crying?” a friend texted.)

Both stressed the “nothing-to-see-here” defense. Paxton did nothing but serve the people of Texas. He helped Paul because he, Paxton, knew what it was like to be unfairly persecuted.

It maybe was not a novel defense. Still, as my lawyer friend pointed out, reasonable doubt is the name of the game, and that’s all it will take to persuade—or provide an excuse for—ten senators to let Paxton skate.

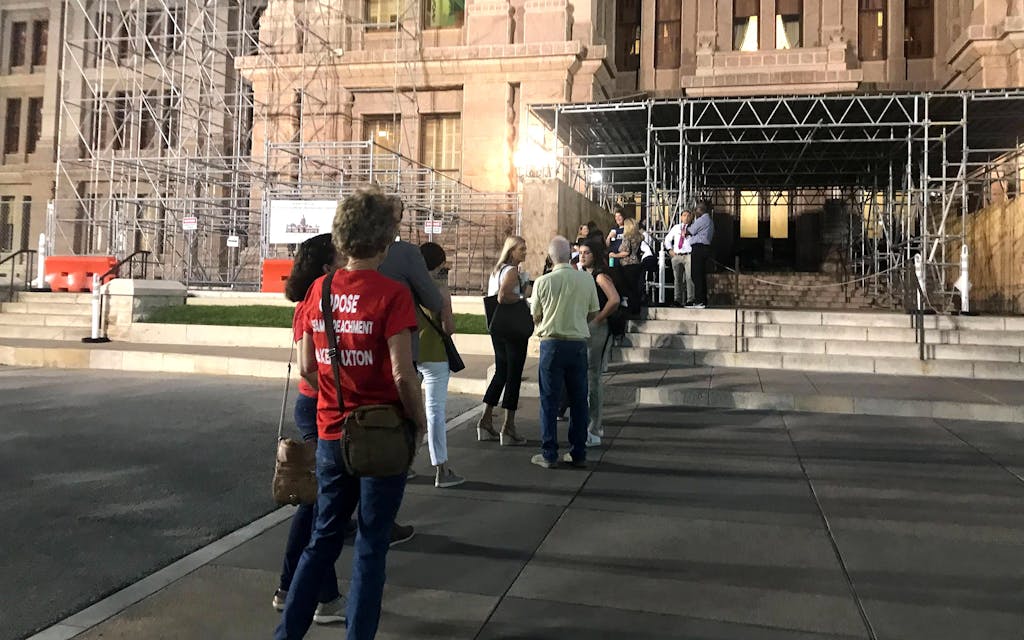

Surveying the Crowd

Mimi Swartz, 2:48 p.m.

Call me Joan Rivers but, during this break in the proceedings, let’s take a look at the fashion in the gallery. There are some folks in flag-based shirts and caps—stars and stripes, red, white, and blue. One or two are donning glittery gimme caps. There’s some MAGA wear—caps and T-shirts with the image of Trump. But mostly there is a small sea of red pro-Paxton T-shirts, including those worn by one group of women. The T-shirts mostly, but not entirely, support Angela Paxton—backing of the betrayed wife looks to be running high.

Around the gallery there’s lots of fightin’ words as slogans: “I’m a god fearin’, gun supportin’ conservative Votin’ CHRISTIAN.” And “OPPOSE SHAM IMPEACHMENT OF KEN PAXTON.” And “I am a True Texan.” That last slogan seems like grounds for fisticuffs, but so far the anti-Paxton forces are steering clear.

Dan Cogdell’s Opening Statement

Christopher Hooks, 2:35 p.m.

The first part of Paxton’s opening statement came from Tony Buzbee, who came with characteristic trial lawyer bombast. But the rest of his opening statement was delivered by Dan Cogdell, a highly regarded Houston criminal-defense lawyer. Unlike his colleague, Cogdell steered clear of potentially offending the sensibilities of the stuffy Senate, but his statement was otherwise pretty remarkable. His wife is ill, he said, and he probably shouldn’t be here, but his wife rallied him with the admonition that he had to go save democracy. This is bigger than Ken Paxton, he said, apologizing to Ken Paxton, who was no longer in the room.

Buzbee gave the defense’s big thesis—this is all a sham—and it fell to Cogdell to deliver a more intensive refutation of the facts. Which he did, running through some challenges to the evidence his side intends to make.

At one point Cogdell quoted Einstein: “Assumptions are made, and most assumptions are wrong.” To underline the point he added: “When you assume, you make an ass out of you and me.” Later he turned around to Patrick. “How much time do I have left?” About twenty minutes, he was told. “I may give some of those back,” said Cogdell. He ended up yielding only one minute.

The (Alleged) Affair Is No Longer Being Talked Around

Alexandra Samuels, 2:25 p.m.

Tony Buzbee, one of Paxton’s attorneys, was the first person in the impeachment trial to name Paxton’s alleged mistress: Laura Olson. As most who’ve been following the proceedings know by now, Olson’s name was in the House manager’s impeachment documents, and the alleged affair has been reported by a number of media outlets (including Texas Monthly). It’s interesting, still, that Paxton’s defense dropped her name first—almost as if it is trying to get ahead of whatever House impeachment managers (and their lawyers) might say about her. Buzbee claimed, under oath, that there was not a bribe when Nate Paul employed Olson and that her employment was not offered as a favor to Paxton. “It doesn’t hold any water,” Buzbee says of the allegations. “Laura Olson applied for a job. Laura Olson got a job.” Buzbee also said Olson is still doing that same job today.

For those just now catching up, Olson has also worked for state senator Donna Campbell. For the prosecution, Olson is an important figure because in addition to the charges of bribery, an affair will help them show that Paxton wasn’t living up to the Christian values he espoused.

A Lawmaker’s Appeal Versus a Lawyer’s

Christopher Hooks, 2:02 p.m.

The opening statements today were given by state representative Andrew Murr, for the prosecution, and Houston trial lawyer Tony Buzbee, for Paxton’s defense. It was quite a contrast. Buzbee sported an almost Trump-grade tan, an expensive suit, and slicked-back hair. His speech (still ongoing) has been full of bombast. He has attacked the rules set by Dan Patrick, especially the gag order the lieutenant governor placed in the run-up to the trial. He has wondered petulantly if senators had already made up their minds—if there was any point to making the case for the defense at all. And he offered, belatedly, a partial rebuttal of some of the claims made by the defense—launching, at length, into a description of Paxton’s countertopss, which Paul allegedly paid for, as “ratty.” But he primarily made a political case. “If campaign donations were bribes,” he said “everybody in this town would be impeached.”

Murr leaned heavily on Texas imagery and appeals to morality and decency, looking, as he always does, like an Old West lawman, with his prominent moustache. By using his office to benefit a donor, Murr said, Paxton had violated his oath of office, which was, after all, an “oath to God.” Murr says he grew up in rural Texas “in a family deeply affected by political corruption.” Murr’s grandfather was Coke Stevenson, who famously lost the (tainted) 1948 Senate election to Lyndon Johnson. Murr emphasized that Paxton’s accusers, who will later be testifying, were “movement conservatives guided by their faith” and that “until they refused to follow Paxton demands, they were his most trusted advisers.” Paxton was “not the man they thought he was.”

Buzbee is a much more successful lawyer than I am. But the tone he is taking—hectoring and scolding senators, who have extremely healthy self-regard—seems ill-suited to this audience. He’s making a case much better fit for a public rally than for the upper chamber. Murr is a legislator, and he knows how lawmakers like to think of themselves as the embodiment of a certain set of values and political traditions. His case seems better fit for this room. But, of course, it may not make a difference.

Different Inspirations for the Opening Statements

Michael Hardy, 1:47 p.m.

Representative Andrew Murr, a House impeachment manager, began his opening statement with what he called a favorite Abraham Lincoln quote of his grandfather, Texas governor Coke Stevenson: “Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.” Unfortunately for Stevenson and Murr, Lincoln never said that. Ken Paxton’s attorney Tony Buzbee took a different tack, opening his remarks with a quote from Shakespeare’s Macbeth, slamming the case against his client as “full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Where Is Ken Paxton?

Alexandra Samuels, 1:20 p.m.

After Paxton’s lawyer, Tony Buzbee, pleaded not guilty to all sixteen impeachment articles for which his client is currently being tried, it appears that Paxton . . . skedaddled. Rusty Hardin, one of the lawyers for the House impeachment team, pointed out that Paxton is no longer on the Senate floor and questioned why that is—to which Paxton’s defense responded that the attorney general simply doesn’t have to be! The rules, they said, require Paxton to be present only at the beginning of proceedings. Patrick’s legal advisory team and some members of the Texas House impeachment team are deliberating the rules now and whether Paxton is required to be on the Senate floor as the trial proceeds.

What the Motion-to-Dismiss Votes Tell Us About Paxton’s Prospects

Christopher Hooks, 12:58 p.m.

Are there votes in the Senate to convict Ken Paxton of anything? Is he in any real danger here? Sure. There’s no reason so far to doubt it. The first test was whether Paxton could get any of the impeachment charges dismissed on the trial’s first day. He failed to do so, by pretty lopsided margins.

But for the purposes of making the math easier, we should perhaps ask whether Paxton can put together the ten votes he needs to be acquitted. This morning, he had ten votes on one motion to skip a single charge and between six and eight on most others. On at least one charge, then, he would seem to already have the number he needs to be acquitted. (It’s difficult, if not impossible, to imagine the folks who didn’t want to hear the evidence changing their minds once they’ve heard the evidence.) On other charges, he needs to win one more. On quite a few others, he would seem to need four more—four votes out of the twelve Republicans who did not vote to dismiss.

He needs to win those votes either with a substantive argument—the evidence is wrong—or a political argument, which is to say, convincing senators that the charge does not warrant the dramatic step of his removal from office. It’s easy to imagine that happening. But it’s also not guaranteed. And Paxton’s team needs to win on all sixteen counts, while the House impeachment managers need to convince senators on only one count.

Paxton’s best shot is if his friends are able to apply enough pressure to convince a few more senators that conviction, even if warranted, would be inadvisable. Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s former adviser, made a lot of noise recently when he announced he was going to war in Texas on behalf of Paxton. He would be targeting a different set of six senators—Kelly Hancock, Bryan Hughes, Mayes Middleton, Charles Perry, Charles Schwertner, and Drew Springer—who he said were squishes on impeachment.

There’s time for this plan to work, of course, but it has shown little evidence of bearing fruit so far. Of the six, only Perry and Schwertner voted yes on any of the dismissal motions. All others, solid conservatives, voted no on every one.

What Comes Next?

Alexandra Samuels, 12:30 p.m.

While the trial is on break, a few notes on what’s to come. The Senate, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick said today, “is committed to conducting a fair and impartial trial.”

- Each day will begin at 9 a.m. central and last until at least 6 p.m.

- Jurors (or, senators) will occasionally meet on Saturdays too—though not this week.

- Patrick also says that senators will break for lunch at around 12:15 p.m. each day and take additional twenty-minute breaks after every ninety minutes or so.

Paxton Is Pleading Not Guilty—With Some Tony Buzbee Flair

Mimi Swartz, 11:57 a.m.

While the articles of impeachment are being read before Paxton’s team states how it will plead, Paxton attorney Tony Buzbee provided the answers. “Not guilty” does not suffice. “Those are all false” and “those allegations are offensive,” Buzbee said, after hearing charges read, only then adding, “therefore Ken Paxton pleads not guilty.”

Hardin eventually objected to the “speech making” by Buzbee, and Dan Patrick sustained the objection. Buzbee then began using his body language and his word emphasis—“NOT guilty”—to radiate outrage.

Ken Paxton Won’t Be Compelled to Take the Stand

Christopher Hooks, 11:40 a.m.

The Senate is taking a short break, but just before, Patrick made a significant announcement: Paxton cannot be compelled to testify. And it feels safe to assume that if he is not forced to, he won’t. We’ll likely be spared the spectacle of Dick DeGuerin asking Paxton why his allegedly affair-related Uber account recorded so many trips to fast-food joints.

This is an eminently sensible ruling for a criminal trial. If Paxton was accused of murder, he could not be forced to testify against himself either, of course. The issue is that the political message of Paxton’s team has been that Paxton would love absolutely nothing more than to clear the air, that he had only been impeached in the first place because the House had been acting in the dark of night. When Paxton could speak for himself, they promised, the light would shine and the air would clear.

Not so much, it turns out. And because this is not actually a murder trial but a political spectacle masquerading as a trial, we are within our rights to judge Paxton on his willingness to speak for himself.

Angela Paxton Watch

Mimi Swartz, 11:24 a.m.

It’s hard to say whether Angela Paxton had a tough morning. Like her husband, she was as still as a sphinx, occasionally reading papers, often just quietly listening, letting her red suit do the talking. At one point she did stand and turn to the gallery, blowing a kiss to someone. I don’t think she was aiming for the reporters in the balcony.

Where We Go From Here

Alexandra Samuels, 11:19 a.m.

Paxton’s team lost on all of its pretrial motions that required a Senate vote. Here’s how the trial will proceed, according to Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick:

Each side has:

1 hour for opening statements

24 hours to present evidence

1 hour of rebuttal

1 hour for closing arguments

Patrick also has said that Paxton cannot be compelled to testify.

A Closer Look at Who’s Standing by Paxton and Who Isn’t

Christopher Hooks, 11:05 a.m.

We promised you excitement, and so far we’re liars: the trial so far has mostly consisted of votes on procedural motions to dismiss some or all of the articles of impeachment Paxton will eventually face. Each motion has been different, and the voting contingents have varied a little, but most (failed) efforts to dismiss charges have had six or eight yes votes (with a few earning nine and ten). That’s out of thirty voting senators, eighteen of whom are Republicans.

Who are the always-yes votes? Folks you’d expect. Strongly ideological right-wingers. Good soldiers. Lois Kolkhorst and Donna Campbell, of Brenham and New Braunfels, respectively. Paul Bettencourt of Houston, normally a close ally of Dan Patrick’s. Brandon Creighton, of Montgomery County. Tan Parker, crown prince of Flower Mound. Bob Hall, the state’s foremost activist on the issue of electromagnetic pulse weapons. Hall has managed to inject just a little bit of the Senate’s characteristic grandstanding into today’s events. As the voice votes on the motions proceed, he has been particularly enthusiastic about his “yeas.”

None of the six are voting yes because of the much-discussed pressure campaign against state senators. This is all squarely in line with what they believe. Indeed, the pressure campaign, the promises to primary anyone who supports the impeachment, does not show evidence of carrying the day here. Of the six senators up for reelection in 2024—this will probably be too distant in 2026 to matter much—three are voting to dismiss and three are voting to continue.

It isn’t terribly surprising that these motions are failing, but Paxton’s supporters in the room seem tense, with one woman holding her face in her hands as the first vote failed. If you take in mostly conservative media, it’s possible you thought the Senate was going to throw out impeachment managers on their ass today.

Kevin Sparks Bites the Hand That Feeds Him

Michael Hardy, 10:53 a.m.

Perhaps no senator owes more to Dan Patrick than Kevin Sparks. A right-wing Midland oilman, Sparks won election in 2022 after Patrick forced his predecessor, Kel Seliger, into early retirement by gerrymandering his district. Sparks received endorsements from Donald Trump and financial backing from Defend Texas Liberty—a PAC funded by right-wing billionaires Tim Dunn and Farris Wilks. Dunn and Wilks have also been among the biggest supporters of Ken Paxton—which makes it all the more surprising that Sparks has regularly voted against Paxton this morning. On the major motions, Sparks has voted to proceed with the trial. That doesn’t mean he’s going to convict, but it does show a somewhat unusual degree of independence.

Early Losses for Team Paxton

Mimi Swartz, 10:35 a.m.

Torpor is setting in. I wonder if the defense is reconsidering all the motions they filed in Paxton’s favor. The tallies aren’t going their way, and folks in the gallery are beginning to use these votes, especially the recounts, as an opportunity for restroom breaks.

The Senate Is Proving (Somewhat) Unpredictable. That’s Unusual.

Christopher Hooks, 10:21 a.m.

The Texas Senate is boring, conventional wisdom says. In this case, conventional wisdom is right. When the legislative session starts, journalists in their bureaus have to divvy up responsibilities. Nearly everyone wants the House. The House is exciting and chaotic and makes news regularly. The Senate is quiet and next to nothing ever happens on the floor that hasn’t been carefully choreographed behind closed doors hours, or days, beforehand. The carpet is an unpleasant shade of green and the room reeks of futility. To be in this room, where so much hangs in the balance and the outcome feels genuinely uncertain, is a rather shocking inversion of some of the fundamental rules of Texas politics.

What the First Senate Votes Tell Us About Conviction Prospects

Christopher Hooks, 10:02 a.m.

The first three votes on attempts to dismiss certain impeachment charges—a referendum on whether this trial should be happening at all—did not go well for Ken Paxton. The first, which would have ended the whole proceeding, failed 6 to 24; the second, which would have nullified impeachment charges relating to subjects from before the beginning of Paxton’s current term, failed 8 to 22. A third, similar motion also failed 8 to 22. There were yea votes from right-wing senators including Bob Hall, Donna Campbell, and Brandon Creighton—no surprise there—but also no votes from a few Republican stalwarts such as Bryan Hughes.

You can look at this either way. On the one hand, a majority of Republican senators are opting out of an easy opportunity to cut the proceedings short. On the other, nearly half—eight of eighteen Republican senators, since Angela Paxton is not voting—are ready to end this now. And while it’s easy to imagine Republican senators voting to proceed and then voting against conviction later, it is much more difficult to imagine today’s eight votes to dismiss becoming votes to convict.

Trump World Weighs In Again

Alexandra Samuels, 9:50 a.m.

As the impeachment trial gets underway, former President Donald Trump’s son Don Jr. issued a tweet predicting that Paxton will “survive and will continue to combat the Swamp in Texas to put America First.” Many of Paxton’s allies, including Don Jr., have publicly and privately threatened to fund primary challengers against any Republican senators who might vote against Paxton. In his tweet, Don Jr. said he was “looking forward to the upcoming 2024 primary season. RINO hunting season starts soon!!!”

The Trial Will Go On, for Now

Christopher Hooks, 9:46 a.m.

Our first test of what Republican senators are thinking about the proceedings has commenced. The two sides have filed 24 pretrial motions, some of which would see some or all of the impeachment charges dismissed. The senators will vote on each one, in what could be a lengthy process.

First up: Motion 22. A simple majority vote could have made this a very short day, but it failed 24–6.

Determining What Will Be Discussed at the Trial

Mimi Swartz, 9:39 a.m.

The first order of business is procedural: determining by majority vote which of the sixteen counts against Paxton might be eliminated by the judge and Senate. Or, to paraphrase one of the attorneys close to the proceedings, the lawyers will find out which case they are actually trying.

The first vote is on Motion 22, “No Evidence motion for Summary Judgment.” If a majority votes yes, this could end the trial before it begins.

Checking In on Angela Paxton

Mimi Swartz, 9:31 a.m.

Angela Paxton wasn’t sworn in—Dan Patrick noted that only voting jurors are being sworn in. She looks resplendent watching in a scarlet suit, driving the point home.

So, About That Bible the Senators Are Swearing On

Michael Hardy, 9:18 a.m.

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick is currently swearing in each Texas senator on what he described as the Sam Houston Bible. The bible is certainly old—its title page states it was printed in 1816, and it’s been used to inaugurate Texas governors and other elected officials for more than 150 years—but there is little evidence that it ever belonged to the first president of the Republic of Texas. According to the Texas Supreme Court’s website, “a well-known but apocryphal legend claims that Sam Houston owned the Bible, and personally gifted it to the Supreme Court during the Republic.”

For those of you who skipped English class, apocryphal means “things that ain’t so.”

The Opening Prayer

Christopher Hooks, 9:13 a.m.

At 8:59, Dan Patrick walked into the chamber to begin the trial. Senators filed in: Angela Paxton, who will face a bright spotlight for the rest of the trial, is wearing bright red, seemingly a show of defiance.

Patrick explained, to what he knows is an audience unfamiliar with the upper chamber, that each day will start with a prayer from a different senator. State senator Phil King , today’s pick, beseeched God for wisdom in the face of the task at hand. God willing, Senator King, but if God granted wisdom to those who merely asked for it, the Texas Legislature would look a lot different.

And We’re Off

Mimi Swartz, 9:03 a.m.

The proceedings are opening with a prayer from Phil King, a Republican state senator from Weatherford.

What We’re Watching Closely Today

TM Staff, 8:55 a.m.

Right ahead of the start of our live blog our team members are picking the things they’ll be paying special attention to today:

Michael Hardy: I’m excited to see the hundred-plus witnesses assembled all together in the Senate chamber, as Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick has ordered. It sounds like the final episode of Seinfeld, in which all the bit characters from the show’s nine seasons return to testify against Jerry and the gang.

Christopher Hooks: I’m looking forward to seeing how Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick handles what might be the most high-profile, and high-pressure, event of his career in public office

Ben Rowen: Senator Angela Paxton, who will not be voting in the trial but will be present, and will hear salacious testimony concerning her husband’s (alleged) infidelity. In the past, she’s told audiences at rallies that she’s come to terms with him coming home late from long days “su[ing] Obama” . . . no word yet on her reaction to him coming home late from the club.

Alexandra Samuels: Before managers can start presenting evidence, senators will vote on whether to grant Paxton’s requests to dismiss every article of impeachment. (A simple majority—sixteen senators—is needed to dismiss an article prior to the trial). Do I think it’s likely that the entire case will get thrown out before the trial even begins? No. But we might get some insight into what certain Republican senators (particularly those with ties/conflicts of interest related to Paxton) are thinking based on their yea or nay votes for dismissal.

Dan Solomon: I’m curious whether Steve Bannon or other national carnival barkers will make an appearance. And I’m hoping that I emerge from this experience having learned as little as possible about Paxton’s sex life.

Mimi Swartz: I want to feel the mood of the room, as opposed to seeing who is there. How tense will it be? And I also look forward to the defense’s opening statements, so I can finally hear their . . . defense.

Forrest Wilder: The main action will, of course, be happening in the Texas Senate. But I’m also going to be paying close attention to the proxy war unfolding outside the Capitol between the two super-wealthy special-interest coalitions that are lined up on either side of the impeachment trial. How will Texans for Lawsuit Reform and its anti-Paxton allies try to apply pressure? What other surprises does pro-Paxton Defend Texas Liberty have in store? Expect dirty tricks and plenty of rat f—ing.

Where Is Everyone?

Christopher Hooks, 8:50 am.

One question about today’s hearings: how many gawkers would show up. There are a fair amount of folks in the Senate gallery for a Tuesday morning outside of session, but not that many, all told. The trial starts at nine, so a few are still filtering in, but there are only maybe 150 folks in seats, about a quarter of the gallery’s capacity. Maybe half of the gallery is off limits: most notably, the bank of seats at the front wall of the Senate, where spectators could watch the faces of senators as they take in the trial, is cordoned off.

During session, it’s common for activists to show up in the gallery wearing shirts with the same color, showing those on the floor that they’re here and they care. There are maybe two dozen in red shirts offering Paxton their support, many of them in shirts advertising the True Texas Project, which evolved from a DFW-area tea party group. They applauded just now as Angela Paxton, Ken’s wife, came onto the floor and hugged him.

But that’s a pretty small turnout. Most folks here seem like rubberneckers. In line I spoke to one man who said he was a Republican voter who knew Paxton from his time living in DFW. Paxton, he said, had the unsettling habit of claiming to be a regular attendee of whatever church congregation he happened to be speaking before. This was an early sign to the man that the attorney general wasn’t to be trusted. Subsequent events, he said, had borne this impression out.

The Man of the Hour Arrives

Mimi Swartz, 8:46 a.m.

Ken Paxton just showed up. Looks calm and good-natured, not like a man facing potential loss of employment. But maybe because that’s not what he’s facing. We will see.

Surveying the Crowd

Mimi Swartz, 8:43 a.m.

Well, for an impeachment as big a deal as this, it’s pretty quiet. Most of the people here are reporters, except for a red-T-shirted group who identify as Paxton lovers and RINO hunters. The lawyers are here. Cogdell hasn’t put his jacket on, Tony Buzbee has the best tan and is practicing already at the lectern, and Rusty Hardin is donning a nice tan summer suit and looking cheerful. (“Rusty’s suit matches his hair,” someone in the crowd behind me just said.) One or two members of the jury—that is, the Senate—are here now, but most appear to be waiting until the appointed hour, 9 a.m., to show up.

The “Don’t Boo, You Already Voted” Defense

Ben Rowen, 8:39 a.m.

A key part of the Paxton defense is that his alleged misdeeds have been so well-known for years that Texans, in reelecting him, decided to give him a pass. Belief in direct democracy is not a typical principle of the Texas attorney general’s office, nor is Paxton’s defense one that would hold up in a court of law—nor is it certain to hold up in a court of the Texas Senate. But Paxton is correct on one thing: voters have given him a pass for years, electing him as AG three times after he’d furbished a reputation for (alleged) petty grift, twice after he was indicted on felony securities fraud charges, and once after whistleblowers in his office accused him of bribery. Why?

Well, in part—even though there was tons of reporting on it—voters simply didn’t know much about Paxton’s alleged criminality: in April of last year, a poll found only 18 percent of registered voters, and 12 percent of Republican ones, had “heard a lot” about the reported misdeeds. That appears to be changing (see Alex’s post below). But the main reason is that folks just care less these days about political scandal. Bodies of research on the topic have found voters care a lot less in today’s hyperpartisan climate than they did in the past—so much so that one researcher told me his advice to any candidate beset by impropriety would be to never resign. As one Republican voter told my colleague Michael Hardy as she dismissed the allegations against Paxton, “The government wants to discredit anyone trying to improve the country and uphold the Constitution.”

Last year, I set out to find an “Edwin Edwards” test for Paxton—that is, a standard for what type of misdeed could sink him electorally, à la the one a former Louisiana governor set for himself (“The only way I can lose is if I’m caught in bed with either a dead girl or a live boy,” Edwards said in 1983). A group of political scientists I chatted with didn’t think there was one. “If there was something that we might think of as bad enough that he would surely lose,” Scott Basinger, a political scientist at the University of Houston who runs a database of political scandals, told me, “as long as there were a couple weeks before the election, I think there’s also something ‘good enough’ for his base that he could do that would probably distract people from it.”

Unfortunately for Paxton, while his base can win elections in Texas, whether it can win trials in the Texas Senate by proxy is ever so slightly less certain. Live girls, too, might matter there.

Dispatches From the Court of Public Opinion

Alexandra Samuels, 8:19 a.m.

For months, Paxton and his political allies—at least those not under Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick’s gag order—have dismissed all talk of the attorney general’s alleged shady ethics, suggesting that Paxton is a victim of political persecution. But while Paxton’s friends have taken up his defense in recent weeks, voters have been somewhat less forgiving.

A poll of registered voters, conducted by the University of Texas at Austin from August 19–28, registered Paxton’s lowest job approval rating in the survey’s history. Just 27 percent of respondents said that they approved of his job performance, compared with 46 percent who disapproved. In June, a little after the House voted to impeach Paxton, the split was 30–41, and in April, before impeachment was on anyone’s mind, it was 39–35.

The same August survey also found that 47 percent of Texas’s voters think that Paxton did things as attorney general that justify removing him from office; 18 percent did not. The rest said they didn’t have an opinion.

Even when Democrats and independents are factored out, Paxton is no longer overwhelmingly popular. Among his fellow Republicans, about one fourth (24 percent) said Paxton’s removal from office was legitimate. Another plurality of Republicans (32 percent) said that Paxton’s actions weren’t enough to warrant him losing his seat in the AG’s office. Most Republicans (43 percent) said they did not know or had no opinion.

The poll also showed Paxton’s approval rating slipping well behind those of nearly all of the top statewide Republicans. Governor Greg Abbott, for instance, had a 47 percent approval rating as of June, compared with a 42 percent disapproval rating. U.S. senator Ted Cruz, who is up for reelection in 2026, netted similar numbers: 45–42, according to the Texas Politics Project.

Greetings From the Line at the Capitol

Katy Vine, 8:13 a.m.

Though not quite attracting the throngs of a Taylor Swift concert, the trial has proven to be a crowd drawer. Before dawn, two women held places for reporters out in front of the wrought iron gates of the Capitol complex. On the east side of the building, someone tried to run onto the lawn before 6 a.m. and a trooper asked her to back up behind the gates. Then at 6, the gates opened and it was a Black Friday scene: folks began forming a queue—mostly reporters, although there was a group that drove in from the McKinney area wearing red T-shirts supporting Paxton.

Putting Paxton in His Texas Context

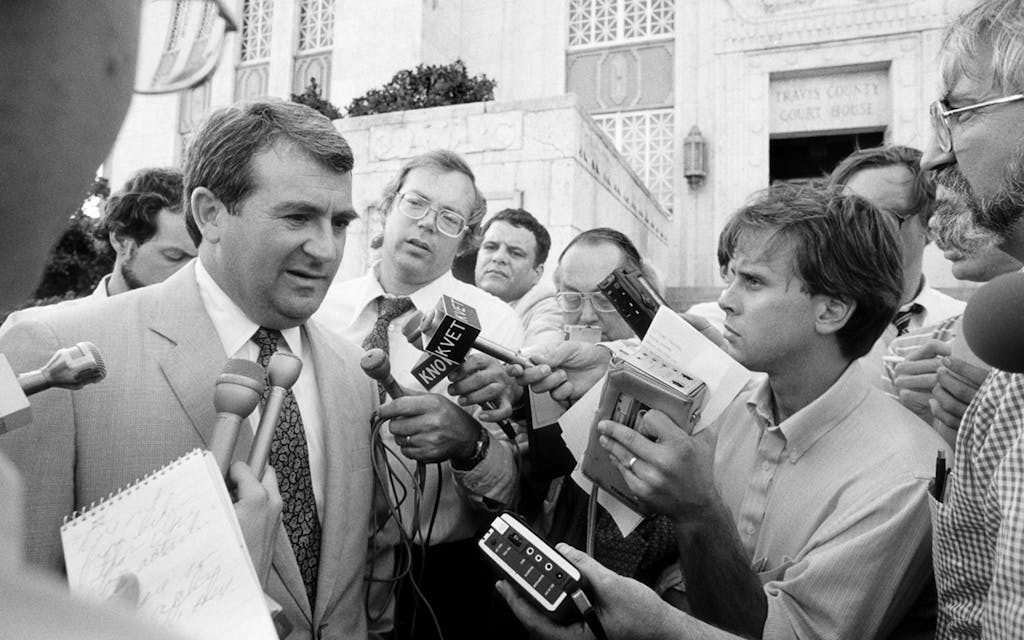

Michael Hardy, 8:00 a.m.

Ken Paxton isn’t the first Texas attorney general to receive a felony indictment. That dubious distinction belongs to Jim Mattox, the late Dallas Democrat who called himself “the people’s lawyer” and served as the state’s top law enforcement official from 1983 to 1991. Like Paxton—whose cozy relationship with Austin developer Nate Paul is at the center of his Senate trial—Mattox got in trouble for helping out a deep-pocketed friend, rancher and oil tycoon Clinton Manges. (In 1984, the mercurial Manges was the subject of a two-part, National Magazine Award–winning Texas Monthly profile by Paul Burka.)

In 1983, Mattox used his position as attorney general to intervene in a $1.7 billion lawsuit Manges had filed against Mobil Oil for allegedly violating the terms of its leases on his South Texas ranch. Mattox claimed he was representing the state’s interest—if they won, both Manges and Texas stood to make a windfall—but a questionable financial transaction raised the possibility of a quid pro quo. During the previous year’s political campaign, Mattox’s siblings had taken out a $125,000 loan from a Manges-affiliated bank. Around the same time, Mattox loaned his campaign $125,000.

Mobil Oil’s lawyers at Fulbright and Jaworski found out about the loan and blew the whistle. Mattox responded by threatening, during a taped phone call, to cut off the Houston law firm’s lucrative bond business. That call led a Travis County grand jury to indict Mattox on a felony charge of commercial bribery. A jury acquitted Mattox in 1985—it didn’t always take eight years to bring a case against a sitting AG to trial—and Texas voters reelected him the following year. But the indictment cast a shadow over Mattox’s reputation. He spent the next two decades making unsuccessful runs for governor, U.S. Senate, and attorney general (again), before dying in 2008 at the age of 65.

Is Paxton Even a Good Lawyer?

Michael Hardy, 7:47 a.m.

When Ken Paxton was sworn in as Texas attorney general in 2015, he had some big shoes to fill. His two immediate predecessors, John Cornyn and Greg Abbott, had turned the office into a national powerhouse, attracting some of the most talented conservative attorneys in the country to Austin to wage war on liberalism. (Abbott famously described his job thusly: “I go into the office in the morning, I sue Barack Obama, and then I go home.”) But while Cornyn and Abbott had previously served as Texas Supreme Court justices, Paxton’s legal background was distinctly less impressive, including stints as in-house counsel at J. C. Penney and as a probate attorney.

Still, Paxton had inherited the conservative legal machine built by Cornyn and Abbott. At first it appeared that little would change. Paxton’s indictment on felony securities fraud less than a year into his tenure was an embarrassing distraction for the office’s approximately 750 attorneys, but there was no indication that the well-oiled legal apparatus was in danger of breaking down.

Then, in 2020, eight of Paxton’s top aides accused him of accepting bribes from Austin real estate developer Nate Paul. All of the aides were either fired or resigned, sparking an office-wide exodus. “There was a big brain drain,” said Josh Blackman, a conservative legal scholar at the South Texas College of Law Houston. “A lot of the top lawyers started leaving. It became more difficult for Paxton to keep and recruit talent, because there were a lot of distractions on the side.” At times, some divisions had job vacancy rates of as much as 40 percent.

In December 2020, in a Hail Mary attempt to overturn the presidential election, Paxton filed his infamous, ultimately unsuccessful lawsuit against Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Conspicuously missing from the lawsuit was the name of Texas solicitor general Kyle Hawkins, who resigned the following month. “Paxton has secured some victories in court, but there are a lot of big cases where the lawyers withdrew,” Blackman said.

In fairness, Texas Republicans don’t seem to mind the dysfunction. They’ve elected Paxton three times, picking him over former Texas Supreme Court justices, Bush family scions, and conservative folk heroes. From the base’s perspective, what appears to matter is not Paxton’s effectiveness but his willingness to fight—something he’ll have plenty of opportunities to demonstrate over the coming weeks.

Ken Paxton’s Most Egregious Act Will Not Be Part of His Impeachment Trial

Forrest Wilder, 7:28 a.m.

During the trial of Ken Paxton, we will hear in lurid detail about his many alleged misdeeds—the infidelity, the self-dealing, the greed, the cronyism, the burner phones and the fake Uber account, the Montblanc fountain pen, his bizarre relationship with Nate Paul, the $20,000 countertops (perhaps we’ll finally settle the question of whether they were title or granite), his meddling in his own criminal prosecution in Collin County. . . . Well, it’s tedious to even list it all. Paxton’s years in office have been such a farrago of corruption and scandal that only the most dedicated Paxtonologists can keep up. But what we won’t hear at the trial is much, if any, talk about arguably the worst thing Paxton has ever done.

Lest you’ve forgotten, Ken Paxton tried to overturn the 2020 election. He filed a frivolous lawsuit—one that staffers in the Republican Florida AG’s office called “batshit”—to toss out the election results in four swing states that Joe Biden won in order to install Donald Trump as president. The suit itself was famously a slapdash effort, larded with falsehoods already rejected by the courts and statistical gibberish cooked up by a Trump donor. It was so bad that many observers could only conclude that Paxton was angling for a future pardon from Trump. Regardless, the U.S. Supreme Court briskly dismissed the suit and Paxton now faces two misconduct cases pending before the Texas state bar, either of which could result in his losing his law license.

Paxton may get his comeuppance for attacking democracy, but it won’t come through the impeachment process. As Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick has said, the Senate process is neither a civil trial nor a criminal trial. It’s a political trial. And GOP politics in 2023 means near-total fealty to the party’s de facto leader, Trump. In other words, they ain’t going there. None of the twenty articles filed by the Texas House concern Paxton’s role in the 2020 election. Without a catalyst, the wall-to-wall media coverage of the Senate trial will deal with everything but Paxton’s most egregious act. If anything, it will be Paxton’s attorneys who indirectly raise the issue. In a grand irony, one of Paxton’s chief defenses is that the voters knew about this conduct when they reelected him last year, so removing him from office would be undemocratic! See, overturning elections is contemptible.

Corruption, both the legal and illegal varieties, is endemic to Texas political life. Three of the last five Texas attorneys general—Jim Mattox, Dan Morales, and Paxton—have been criminally indicted. (Mattox was acquitted.) That’s not to say serially unethical officials shouldn’t be held to account. They should. But trying to erase the voters’ choice in order to install your preferred candidate is the stuff of world-historical villainy. Fifty years from now, will anyone remember (the admittedly juicy detail) that Texas’s fifty-first attorney general created a fake Uber account under the name Dave P. to usher his mistress around town? If he’s remembered at all, it will be for his role in one of the nation’s lowest moments.

The MAGA Elephants Never Forget

Alexandra Samuels, 7:14 a.m.

Ken Paxton couldn’t overturn the 2020 election in favor of Donald Trump. But he got something from his efforts to do so: a who’s who of the far right have taken up Paxton’s defense to help him beat the allegations ahead of today’s impeachment proceedings—beginning with his most important friend, the former president.

“Dade Phelan, who is barely a Republican at all and failed the test on voter integrity, wants to impeach one of the most hard working and effective Attorney Generals in the United States, Ken Paxton, who just won re-election with a large number of American Patriots strongly voting for him,” Trump wrote in May on Truth Social, his social media platform, when the Texas House took up impeachment. In another post, he decried the proceedings as “ELECTION INTERFERENCE.”

Trump was joined in defending Paxton by his son, Don Jr., who called the impeachment a “disgrace,” and U.S. senator Ted Cruz, who called it a “travesty.” Like Trump, Cruz implied that the ballot box was the proper venue to judge Paxton’s fitness.

More recently, former Trump aide Steve Bannon interviewed Dallas County GOP activist Lauren Davis and urged his podcast listeners to apply pressure to six Republican senators to vote to acquit: Kelly Hancock of North Richland Hills, Bryan Hughes of Mineola, Mayes Middleton of Galveston, Charles Perry of Lubbock, Charles Schwertner of Georgetown, and Drew Springer of Muenster. “We’re gonna make all these six famous in the days ahead,” Bannon said. Davis elaborated on why she called out at least some of those members in another appearance on Bannon’s show. She claimed that four of them—Hughes, Middleton, Perry, and Springer—may be listening to certain consultants who have “vendettas” against Paxton. While she didn’t name a consultant explicitly, it’s likely that she’s referring to Jordan Berry, an Austin-based consultant who previously worked for Paxton but resigned in 2020.

Conflicts (and Agreements) of Interests

Ben Rowen, 7:01 a.m.

So who exactly does Dan Patrick control? There are 31 senators. Two thirds of them (21) are needed to convict Paxton.

Twelve Democrats serve in the chamber. In typical times, they are kindly thought of as furniture, and unkindly as the victims of Stockholm syndrome. They are usually pliant to Patrick’s will, but with impeachment, as Michael Hardy wrote earlier, all are expected to vote to convict.

That means the pro-impeachment side will need nine Republicans to vote to oust Paxton. You almost never see a single Republican break from his or her caucus in the Senate, for the reasons outlined in prior posts, so getting to nine is a tall order. It’s complicated by three senators having a direct conflict of interest.

- Angela Paxton: Ken’s wife, who represents McKinney and most of Collin County. Per the Senate rules, she will not have a vote, but her presence at the trial leaves the math the same: conviction requires two thirds of the senators present to vote in favor.

- Bryan Hughes: the primary legislative mind behind the infamous abortion bounty law and the leader of the fight against “woke” acronyms: anti-ESG (environmental and social governance), anti-DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion), and anti-CRT (critical race theory). He was a roommate of Paxton’s when they both were early-career legislators (this is a literal jury of peers), but his conflict of interest, legally, is that he is the unnamed “straw requester” in the second article of impeachment. It’s complicated, but in short: Paxton needed someone to request a legal opinion from him on an issue that allegedly would benefit Nate Paul, the developer at the center of many of the bribery charges. Unwittingly, Hughes agreed to do so.

- Donna Campbell: a mostly down-the-line senator from New Braunfels who has long been a Patrick acolyte and is occasionally, in turn for her faithful service, allowed to tilt at windmills such as preventing the United Nations from taking control of the Alamo (it simply wanted to name the Alamo a UNESCO World Heritage site). Paxton’s alleged mistress previously worked for Campbell and is on the House manager’s list of potential witnesses, sources close to the proceedings told Texas Monthly.

Throughout the day we’ll be sharing analysis on which Republicans are considered the likeliest—relatively, of course—to vote to oust Paxton.

Whatever Dan Patrick Wants, Dan Patrick Gets. But What Does He Want?

Ben Rowen, 6:44 a.m.

The Texas Senate is a laboratory of democracy, insofar as the members who compose it are a control (and controlled) group. There isn’t much experimentation in the body: What Dan Patrick, the lieutenant governor, wants, he more or less always gets. So what does Dan Patrick, the judge of the trial, want here?

That’s a tricky question. Patrick is a chronic oversharer—a former radio host who famously got an on-air vasectomy and vowed he was willing to sacrifice himself to save the economy during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. But he imposed a gag order on those involved in the proceedings, and he has been studiously tight-lipped here.

We’re left to read the horoscopes—or in this case, reporting circling around the question while Patrick doesn’t talk about it. On one hand, Patrick and Paxton have long shared a statewide ticket, and are ideologically aligned—freedom fighters against the tyranny of the minority party (Texas libs). On the other hand, there’s a brewing sense the two have a relationship only of convenience: Patrick took a curiously long time to endorse Paxton in 2022, when he had a slate of viable Republican primary opponents, much to the chagrin of the AG’s campaign team.

If convenience is the central concern, pro-Paxton groups are tantalizing Patrick with the promise of a life of leisure on future campaign trails should the Senate let the attorney general skate. Patrick has received a $2 million loan—in addition to a $1 million campaign donation—from Defend Texas Liberty PAC, a pro-Paxton arm of West Texas oilman and far-right megadonor Tim Dunn. That loan, crucially, can be forgiven. Might the Senate’s performance in the trial determine whether Patrick gets the millions, no strings attached?

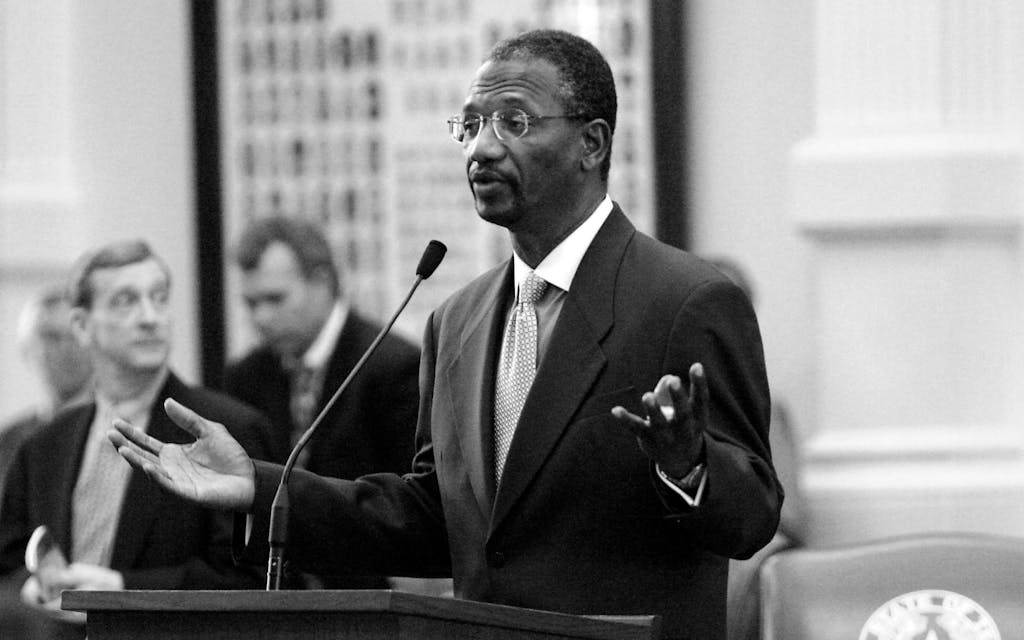

Democrats in Array

Michael Hardy, 6:34 a.m.

Democratic state representative Harold Dutton, who has represented northeast Houston since 1985, has a well-earned reputation for contrarianism. In 2015 he sponsored a bill amendment giving the Texas Education Agency the power to take over school districts if even a single campus earns a failing grade for five straight years. (The TEA used Dutton’s amendment to take over the Houston Independent School District this year—a move opposed by nearly every Houston official.) In 2021 he once again bucked his party by voting for a Republican-sponsored bill banning transgender children from participating in school sports. Earlier this year, tensions between Dutton and fellow lawmakers became so intense that Dutton resigned from the Texas Legislative Black Caucus, accusing the caucus chair of “engaging in stank leadership.”

So it wasn’t a total surprise when the 78-year-old Dutton went his own way during Ken Paxton’s May impeachment hearing in the House. Dutton, who is Black, took the House floor to compare the impeachment hearing to Jim Crow–era discrimination. “There was a time in my history, and in the history of Black people in this country and in this state, that we didn’t get due process,” Dutton declared. “Sometimes they found us guilty and then they had the trial.” This was too much for even some Republican legislators, with representatives Briscoe Cain and Charlie Geren asking Dutton pointed questions about whether Paxton had truly been denied due process.

True to his reputation, Dutton was not swayed. He voted present.

Unfortunately for Paxton, there aren’t any Democrats likely to follow Harold Dutton’s footsteps in the Senate; University of Houston political scientist Brandon Rottinghaus said he expects the chamber’s twelve Democrats to uniformly vote for removal. “I think the party is pretty unified,” he said.

So How Likely Is Conviction?

Christopher Hooks, 6:05 a.m.

Is there a chance that the Senate could convict, and remove Paxton from office permanently? Strong opinions abound. In the Wall Street Journal, strategist Karl Rove, who consulted for Republican campaigns in Texas in the eighties and nineties, wrote that “the end is near” for Paxton. The evidence against Paxton was damning, Rove wrote, and the legal arguments his team had offered—based on the so-called “forgiveness doctrine”—were without factual merit. Both are true. But these days, Rove is more of a commentator on national politics than Texas politics, and his predictive powers have not proved especially strong in either case. It’s perhaps better to understand Rove’s column, along with a similar column in the Journal by former governor Rick Perry, as messaging—attempts by Paxton-skeptical Republicans to push back on the idea, in the discourse, that acquittal is preordained.

And many insiders are happy to say that Paxton’s acquittal is preordained. One told Texas Monthly’s Mimi Swartz that the odds of K-Pax skating were “99.9 percent.” Another told her that “the rule of law doesn’t matter to people anymore.” (I would like to object to that statement, but I’m not sure if I can find the factual grounds to do so.) Intuitively, it makes sense. In the last two decades, you can count times when high-level Texas politicians were held accountable for wrongdoing on no hands. Lethargy and nihilism have set in.

The rest of us, I think, should feel much less certainty. Texas politics is full of events whose outcomes are preordained. The Senate itself never convenes, during regular session, without having a plan for the day cooked up behind closed doors. But this event is unprecedented. We will need to see how it happens, and the form it takes as the days go by, to get a sense of what’s really happening and where it might lead.

This is not a jury trial, and the Senate is not a courtroom. It might be better to think of the impeachment as a stage play, a theatrical event. The quality of the performances put in by the House impeachment managers as well as Paxton’s defense team, and the public’s reaction to them, could affect the calculations made by senators.

It would be naive to expect that Republican senators have fully open minds going into this. But they do have a somewhat difficult decision to make. Let’s say that you’re a Republican senator who will be voting at the end of this trial, and that you have no particular scruples here—that you’re going to vote the way that is best for you. And let’s say the trial goes poorly for Paxton—that House impeachment managers do a great job of prosecuting, the evidence is strong, and Paxton’s team doesn’t have much in the way of answers.

You know a few things. You know that the AG’s office is a mess under Paxton, unable to prosecute slam-dunk cases, hemorrhaging legal talent, and unable to fill many vacancies, and is not likely to get better, because Paxton’s legal problems are only going to get worse. You also know that Paxton stands a decent chance of being convicted of a felony sometime soon after the impeachment trial, for crimes which will have been just run by you. That would be either the state felony securities fraud charges, the trial for which he’s delayed eight years but will finally happen after the Senate impeachment proceedings, or possible future indictments, probably federal ones, to come from the Nate Paul mess. You also know that Paxton has many fans in the Republican Party, and several powerful backers. How do you vote?

Senators have a difficult choice. If they let Paxton skate and he goes to prison, they have avoided Republican anger but look quite bad to everyone else. They have also given Paxton months or years more to let his scandals drag down the party—and possibly the wider Republican brand. On the other hand, most Republican senators are in safe districts. They may not be that worried about looking sleazy if they acquit Paxton and he goes to jail.

On the other hand, they could convict Paxton and incur the wrath of certain parts of the Republican Party. Paxton’s backers, chiefly West Texas oil magnates Tim Dunn and Farris Wilks, are a sometimes formidable force within the party. But they’re not as fearsome as people say. They have a less-than-impressive record of beating their targets in the House, where representatives, with their small districts, are more vulnerable to challenge. In the Senate, their track record is worse, even when their targets are apostate moderates in deep red districts, such as former senator Kel Seliger. And some are not up for reelection until 2026, at which point Paxton may be a distant memory.

Where does a senator with an eye to survival fall? Well, that may depend on how the next few weeks go. Until now, Paxton has shown an almost preternatural, folk hero–esque ability to avoid accountability. But this is the widest gulch he’s ever had to cross, and the shock absorbers on the General Lee are looking pretty worn. Let’s see.

A Nonexhaustive Recap of the Many Allegations Against Paxton

Christopher Hooks, 5:47 a.m.

Hear ye, hear ye: come we now to the Texas Senate, where, after much delay, Johnny Law is finally coming for our boy. The Senate convenes today to hear the impeachment trial of Ken Paxton, the currently suspended attorney general of Texas. Some fifteen years after the then–state representative from McKinney’s first brushes with alleged impropriety, and some eight years after he was indicted on securities fraud charges, Paxton is the closest he’s ever been to experiencing the consequences of his actions.

A few of the impeachment charges Paxton faces relate to the case that resulted in the felony indictments back in 2015, for which he has not yet faced trial. In that case, Paxton allegedly violated securities law by encouraging his legal clients to invest in a technology company—without telling them he was getting a cut. When he was indicted, his allies sought to postpone the trial by using procedural delaying tactics and political pressure, knowing that if he was convicted, he would be barred from serving as attorney general.

But most have to do with the extraordinary relationship between Paxton and Nate Paul, an Austin real estate magnate under federal investigation who was recently indicted on eight felony counts of making false statements to investors. The Senate has published tranches of evidence from House impeachment managers justifying the claim, first made by Paxton’s handpicked aides, that Paxton helped Paul fight that federal investigation in exchange for personal and financial favors, including the employment of Paxton’s alleged mistress.

Some Texans may know that Paxton has a history of ethical improprieties. But few can recite all the details. For many Republican voters, Paxton is simply a member of the team—perhaps a flawed one, but a figure who has been vouched for repeatedly by his ticket mates, such as Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick. Over the month of September, if the Senate trial proceeds as it should, the state is going to become much more familiar with why Paxton is in trouble. The allegations won’t come from, say, his Democratic challenger. They’ll come in the form of testimony from the people who knew him best.

Paxton’s lawyers’ arguments so far have been mostly procedural—that the Senate shouldn’t even consider the charges. But if the Senate does proceed, it is hard to imagine what they might offer as a substantive rebuttal to the underlying charges. If the facts are on your side, the old saying goes, pound the facts. If the law is on your side, pound the law. If the law and facts are against you, pound the table. There are unlikely to be any tables left in the Senate by the time this thing concludes.

The Ken Paxton political project, so far, has depended on voters not looking too closely at the man, while he uses sleight of hand to convince a requisite number of Republican primary voters that he’s on their “team.” He’s about to be subjected to the brightest spotlight of his career.

Welcome, Y’all!

Ben Rowen, 5:30 a.m.

Welcome to day one of the Texas Monthly Ken Paxton impeachment live blog. If you’re like us, you’ve gotten up extra early to prepare to follow the proceedings, which start at 9 a.m. Maybe you’re angling to get one of the first come, first served tickets for entry into the Senate Gallery. If so, good luck! Maybe the burner phone on which you keep your secret Uber account was irritatingly buzzing. We’re not judging (we’ll leave that to the senators). Or maybe you’re just plain excited for some political theatrics. We are too, and we’ll be here for you through the end of today’s proceedings at 6 p.m., and back again tomorrow.

This morning the circus finally arrives in town. It’s been ten years since Ken Paxton was first caught on a security camera pilfering another lawyer’s Montblanc pen, eight years since he was indicted on felony securities fraud charges, three years since eight whistleblowers went to the FBI with allegations that Paxton was abusing his office, three months since the House impeached Paxton on twenty counts, and a month and a half since Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick issued a gag order preventing parties involved in the proceedings from speaking about it. Now, at long last, we will get to hear allegations from witnesses, the defense from Paxton’s team, and hours of sordid testimony. Through it all, Texas Monthly will bring you insight and analysis of what’s happening—from inside the chamber, from outside the Capitol, and, perhaps, from a bar or two where insiders are watching the trial like it’s the Super Bowl.

Much more to come. For now, if you want to catch up on how we got here, what will be discussed, and who will be here, here’s a cheat sheet, courtesy of Mimi Swartz. Christopher Hooks has you covered on the story of how the Texas House came to impeach Paxton back in May. And, if you want to dive deeper into the archives, here’s a page with all our Paxton coverage over the years.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Legislature

- Ken Paxton

- Dan Patrick