For years, the tantalizing prospect of Texas becoming a “purple” battleground state has motivated Democrats—who have had their hopes dashed in election after election. However, the 2018 midterms showed cracks in the GOP’s hold on the state, with Democrats picking up congressional seats in districts that were drawn by Republican mapmakers to be easy holds. Now polling suggests that 2020 could see further gains by Democrats.

While all eyes are on the presidential campaign, and, er, some eyes are on the surprisingly low-profile Senate race between GOP incumbent John Cornyn and Democratic challenger MJ Hegar, the fiercest battles in Texas are over seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Four years ago, the state had just one competitive congressional race; this year, there are a dozen races both parties are acting as if they’ve got a real shot at winning.

Today, we’re continuing our “Get to Know a Swing District” series with a look at Texas’s Tenth Congressional District.

The District

History

Texas’s Tenth Congressional District was first drawn back in 1883 and held by pro-Union Democrat John Hancock (not the one with the fancy signature). Outside of a four-year blip near the turn of the twentieth century, the district—which then contained the majority of Austin—remained a Democratic stronghold for 120 years. Most notably, Lyndon Baines Johnson represented the Tenth from 1937 to 1949, before leaving to pursue a seat in the U.S. Senate and, eventually, the presidency. Just two decades ago, the district was as blue as it got: Republicans didn’t even bother fielding an opponent to Democrat Lloyd Doggett from 1998 to 2002.

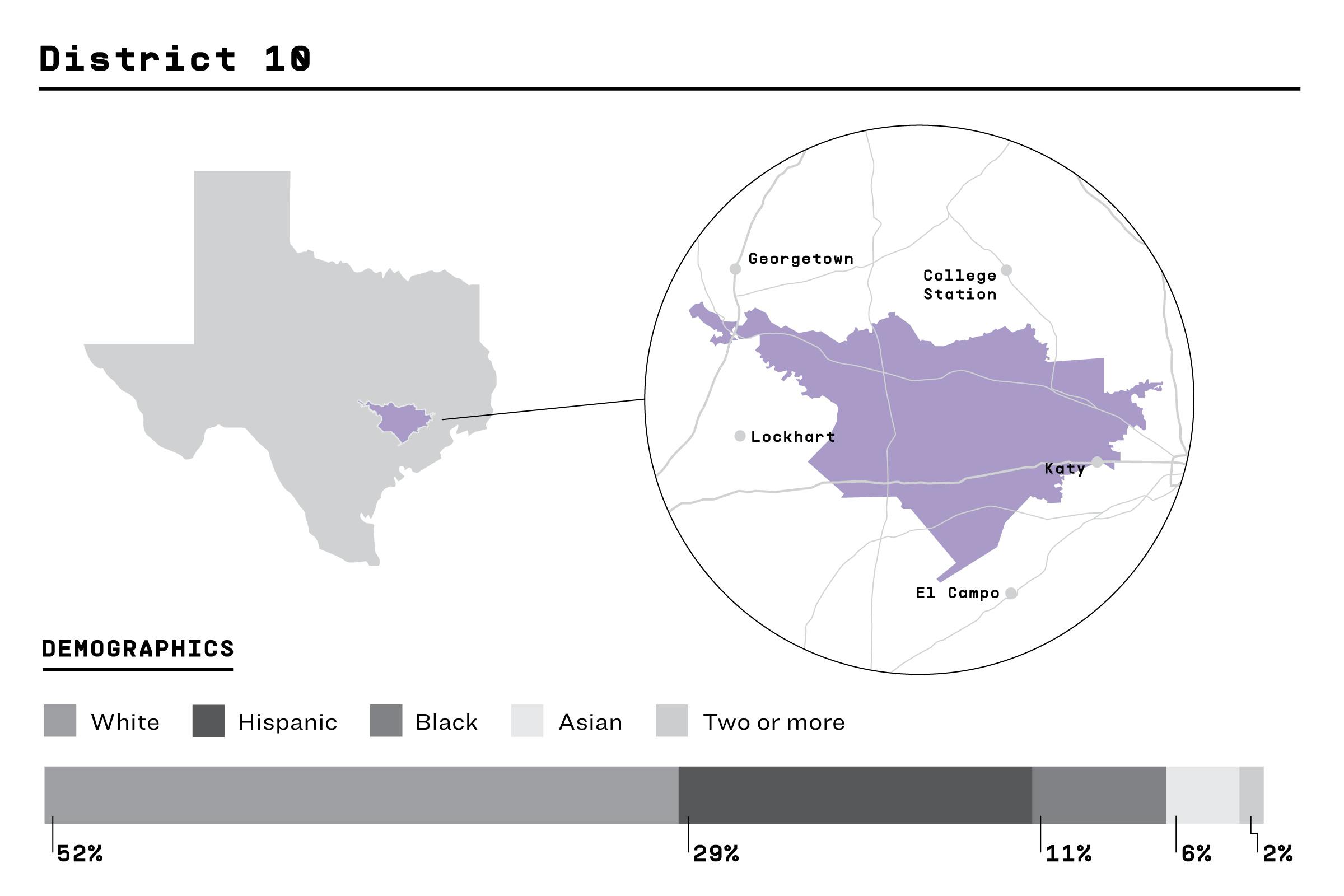

Redistricting did a number on TX-10, though. It was one of several districts redrawn in 2003 to dilute Democratic-voting Austinites by dividing them among multiple districts dominated by GOP-leaning voters in rural parts of the state (see also: TX-17, TX-21, and TX-25). The Tenth now includes a tiny sliver of Travis County, where Austin is located, as well as parts of Harris County, home of Houston, and stretches through the rural areas between those two cities. The dynamics of the Tenth have flipped: in 2004, after Doggett was redistricted out of TX-10, Democrats declined to put up a challenger to Republican Michael McCaul, who’s held the seat ever since.

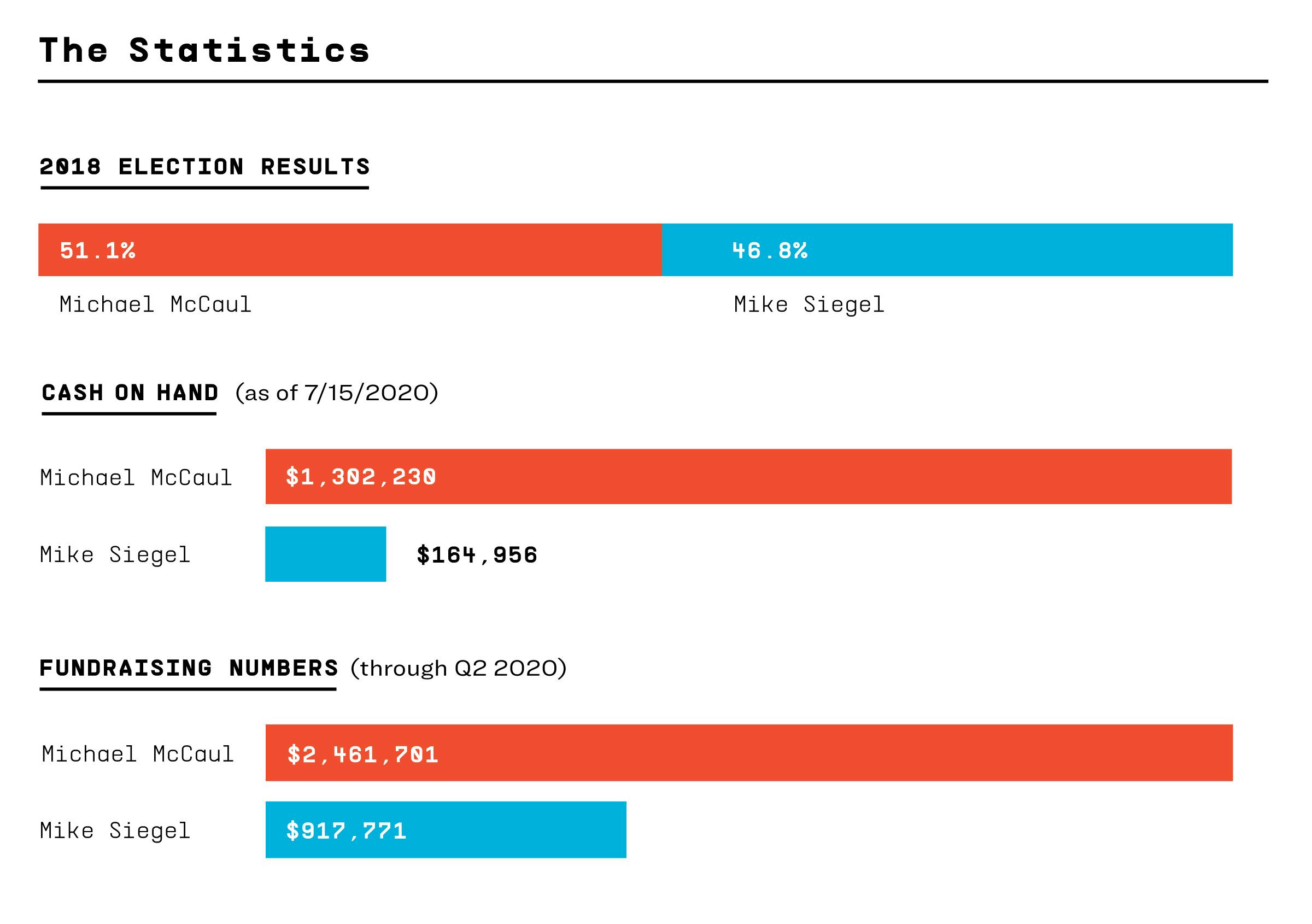

Democrats have run in the Tenth since then, but for most of McCaul’s tenure, their presence on the ballot barely registered in the ultra-red district. But in 2018, Mike Siegel, running as a progressive Democrat, came within 4.3 points of unseating McCaul. In 2020, Siegel won the Democratic primary again, setting up a rematch of one of 2018’s more surprisingly competitive races.

What It’s Shaped Like

The district looks like the silhouette of a predatory bird in mid-flight. Its talon is poised at the edge of Lavaca County, its beak overlooks Interstate 10 around Gonzalez, and one wing stretches west of Austin toward Cedar Park, while the other, in mid-flap, reaches as far east as the Houston suburb of Tomball.

The Tenth is big and oddly shaped is what we’re saying. The district includes Austin’s more conservative and wealthy western suburbs, as well as its more diverse north-central core—where many voters are represented by a different member of Congress than their neighbors across the street. Those folks do share representation with Texans who live 150 miles away in the Houston suburb of Cypress, as well as those near the infamous Chicken Ranch in La Grange and the Blue Bell ice cream factory in Brenham.

The Candidates

Meet Michael McCaul

Among the 22 Republican members of the state’s Congressional delegation, McCaul, a former federal prosecutor, has been in office longer than 15. He’s built an important role in his party, serving on the Foreign Affairs and Homeland Security committees, and chairing the latter for three terms before Democrats took control of the House in 2018.

As a pre-Trump, pre–tea party GOP congressman, McCaul’s more in the George W. Bush mold than are some of his Trumpier colleagues. His campaign de-emphasizes partisan politics: on the “economy, education, and energy” section of his website, the first words are “Michael McCaul is working with Democrats.” But he has cast votes with the current president more than 95 percent of the time, including on the border wall and the Trump tax cuts. He also found himself at the center of the mask-wearing debate earlier this month after Trump tested positive for COVID, when photos and video surfaced of him going without a face mask on a United Airlines flight. (McCaul claimed the mask fell off while he was sleeping, though subsequent video indicates he didn’t wear it while awake, either.)

McCaul, whose father-in-law is the founder and former chairman of radio and advertising giant Clear Channel Communications, is one of the richest members of Congress, with a net worth estimated at $113 million. He’s also well funded, having raised more than $2.5 million this cycle, $1.3 million of which he had on hand at of the end of the year’s second quarter.

Meet Mike Siegel

Many of the Democrats looking to flip traditionally red districts in Texas are running as moderates and trying to court conservative suburban voters who may feel alienated by the Trump-era GOP. Not Mike Siegel, a labor lawyer and former public school teacher, whose platform touts issues including the Green New Deal, racial justice, and Medicare for all. Siegel is also focused on labor reform—especially ending “at-will” employment, which allows workers to be fired for any (or no) reason—and dramatically reshaping U.S. housing policy amid the COVID-19 pandemic. He boasts a trio of high-profile endorsements from former Democratic presidential candidates—Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Beto O’Rourke—as well as those of prominent national organizations including the AFL-CIO and Planned Parenthood, and a slew of local politicians, organizations, and newspapers (including the Houston Chronicle).

Siegel has raised $900,000 according to his most recent FEC filing. It’s money he’s been spending at a steady clip: just $164,000 remained as cash on hand at the end of Q2.

The Upshot

Why It Could Flip

The Tenth is changing. Mitt Romney won the district by twenty points in 2012, Trump won by nine points in 2016, and Ted Cruz lost by two-tenths of a percent in 2018. Much of this change has been driven by growth in the urban parts of the district over the last decade, a trend that seems to have kept up after Siegel’s close loss in the 2018 contest: in the last two years, Travis County has added more than 70,000 new voters, while Harris County has added 111,360 to its rolls. (Not every newly registered voter in either county lives in TX-10, of course, but enough of them do to identify the district as one that’s rapidly changing.)

Siegel won Austin by a huge margin in 2018, while McCaul won over voters in the Houston suburbs that year by a narrower (but still comfortable) amount. The rural middle part of the district, meanwhile, also favored McCaul—but 2018 Libertarian party candidate Mike Ryan pulled a whopping 8 percent of the vote outside of Harris and Travis Counties. Siegel could win this year if he runs up the numbers in Austin, keeps it closer in the Houston suburbs, and if the Libertarian on the ballot, Roy Eriksen, can pull votes from McCaul outside of the two cities. (The possibility that third-party candidates could have an impact on close House races led the Texas GOP to sue to keep 44 Libertarians off the ballot earlier this year, though they lost the suit.)

There’s been only one nonpartisan poll of TX-10, and it was an unusual one, focused primarily on congressional term limits—an issue that neither candidate has taken a stance on—and paid for by a pro–term limits organization. Conducted in late July and early August, it found McCaul up by seven points (though the pollsters also said Siegel would win the district if he added term limits to his platform, a finding that is probably dubious). Siegel’s campaign, meanwhile, released an internal poll in early October that showed him behind by two points.

Why It Probably Won’t

The Cook Political Report described the progressive Siegel’s primary triumph over the centrist and better funded Pritesh Ghandi as a “setback” for Democrats looking to take the seat. McCaul has tapped his campaign war chest in an attempt to prove why: In recent weeks, he’s tried to paint Siegel as a police-defunding prison abolitionist with ties to the Austin City Council, which recently cut the city’s law enforcement budget.

Siegel avoids using the phrase “defund the police,” but he does support abolishing private prisons, and one of his high-profile allies is progressive Austin councilmember Greg Casar. Siegel’s progressive platform allows McCaul to draw a contrast between himself and the challenger that candidates in other swing districts can’t do with much sincerity. That may prove useful, as voters in the district don’t seem to cast their ballots based strictly along party lines. Even though Beto O’Rourke got more votes in TX-10 than Ted Cruz in 2018, McCaul won reelection over Siegel. It’s plausible that Biden could get more votes than Trump in the district in November and that McCaul could keep his seat.

The Bottom Line

If Austin turns out in big numbers, and the Houston suburbs prove receptive to a Democrat in the Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez mold, Siegel could win., But the safe assessment here is that the district is more likely to go to the conservative. Cook Political Report rates the district as having a nine-point Republican tilt, and most well-funded, influential incumbents in districts that were drawn specifically for them to win tend to do well during presidential years.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- La Grange

- Brenham

- Austin