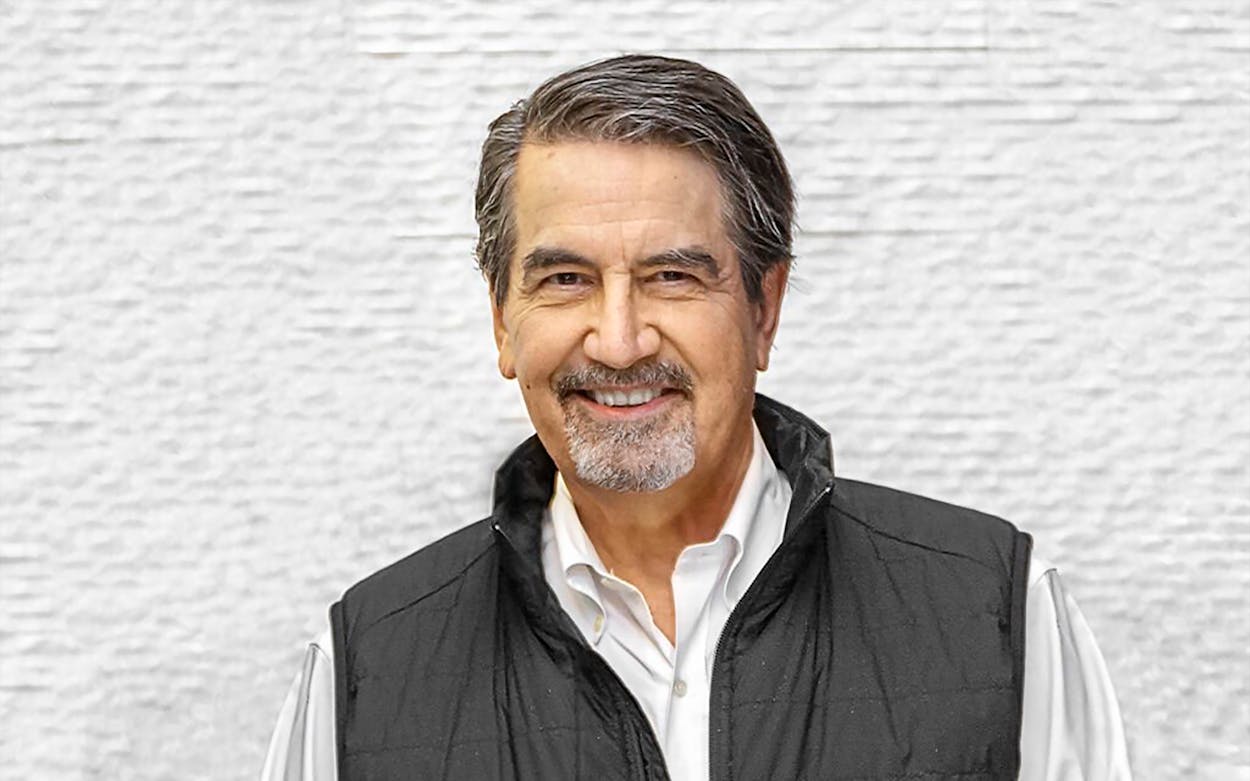

Few people seemed to relish the rough-and-tumble of Dallas politics more than Wick Allison. He loved the city and spent much of his life pushing, prodding, and browbeating to make it a better place. When he cofounded D Magazine, he created for himself an ideal vantage point from which he could shape public opinion and hold local leaders to account. The cover story of the magazine’s first issue, dated October 1974, signaled his ambition: “Power in Dallas: Who Holds the Cards?”

Even now, after hearing the news of his death on Tuesday from bladder cancer, I picture Wick turning his incredulous, withering gaze—eyes narrowed, lips flattened—on dunderheaded decisions by the Dallas establishment. It’s a look I faced myself countless times during the decade-plus when I worked for him. He was an unreasonably demanding boss, which made it all the more rewarding when he was pleased. He might throw back his head and cackle in delight. The remembrances that have piled up in the comments on the obituary by longtime D Magazine editor Tim Rogers testify to how many careers, including my own, he influenced over the decades. “He could make you feel great about yourself or sick to your stomach, sometimes on the same day. He created things—publications, careers, political movements—with a fearless abandon that drove those in his orbit dizzy. Wick was something to behold,” Tim wrote.

Wick (short for his first name, “Lodowick”) was born in Dallas on March 17, 1948, and he grew up in the island suburb of Highland Park, though he would tell you that was in the days before you had to possess the wealth of a hedge fund manager to live there. He graduated from the University of Texas at Austin, where he was editor of the student humor magazine. Following a couple of years in the Army, he attended SMU’s business school just long enough to work out a business plan for the city magazine he envisioned for Dallas. He enlisted his friend Jim Atkinson (now a Texas Monthly contributing editor) to help start D. Financial backing from oil scion Ray Hunt and an assist from Stanley Marcus, who recommended subscriptions to Neiman Marcus customers, led to a successful launch.

The siren song of the New York mediascape took Wick away from Dallas in the eighties, when he founded another magazine, Art and Antiques, and later became publisher of National Review. But he returned to Texas with his wife, Christine, and four daughters, to repurchase D Magazine (with developer Harlan Crow, whom he later bought out) in 1995. Since then, he’s rebuilt the magazine into an influential force in Dallas media. While it often traffics in the service-oriented food, travel, and shopping fare that helps pay the bills for many city magazines, Wick also didn’t hesitate to use D as a bully pulpit from which to influence policy. Perhaps at no time was this more apparent than when, in 2014, it devoted an issue to making the case for tearing down a section of elevated highway through downtown Dallas.

Wick believed in the power of journalism, but he was also keenly aware of its limits. So he co-founded a political action committee, the Coalition for a New Dallas, in 2015 that advocates for a “new urbanism” approach to development, including by tearing out highways and stitching back together the neighborhoods those roads devastated decades before. The organization was run out of the D Magazine office, but its operations were entirely separate (so much so that, more than once, D editors got scooped by other outlets about coalition-generated news).

It’s strange to write all these sentences in past tense. Wick was such an outsized, forceful presence to those of us who spent considerable time learning from and working for him that it’s hard to imagine him gone. He mellowed considerably over the course of the sixteen years I knew him. And while always an avowed conservative, his political views shifted somewhat too, as when he endorsed Barack Obama for president in 2008.

In an age when so many newspapers and magazines have been struggling to stay afloat because of ad revenue getting hoovered up by the likes of Google and Facebook, I appreciated that D’s owners, Wick and Christine, were at the end of the hall and were personally and emotionally invested in the magazine’s success. Wick believed that any diminishment in the quality of our journalism would negatively affect the financial bottom line, a dismayingly rare point of view among today’s media owners. He wasn’t afraid to invest in a good idea, and, just as important, he wasn’t afraid of failing if that idea didn’t work out. I wish every news organization had a fearless champion like Wick at the helm. Our cities, and the whole country, would be the better for it.