It had been two years since Riaz and Zarmeena Sardar Khil had seen their families. In 2019, the husband and wife and their baby daughter, Lina, had emigrated from a rural town in Afghanistan to seek safety in the U.S., leaving behind their siblings. But in mid-December 2021, their families finally had occasion for a reunion. Riaz’s brother, and Zarmeena’s brothers, were U.S. contractors and had been evacuated from Afghanistan as U.S. troops withdrew from the country and it fell under Taliban control. They had made it to San Antonio, where the Sardar Khils had settled. As Riaz wrapped up his shift at a logistics company on December 20, he was eagerly awaiting his first full family dinner since arriving in the U.S.

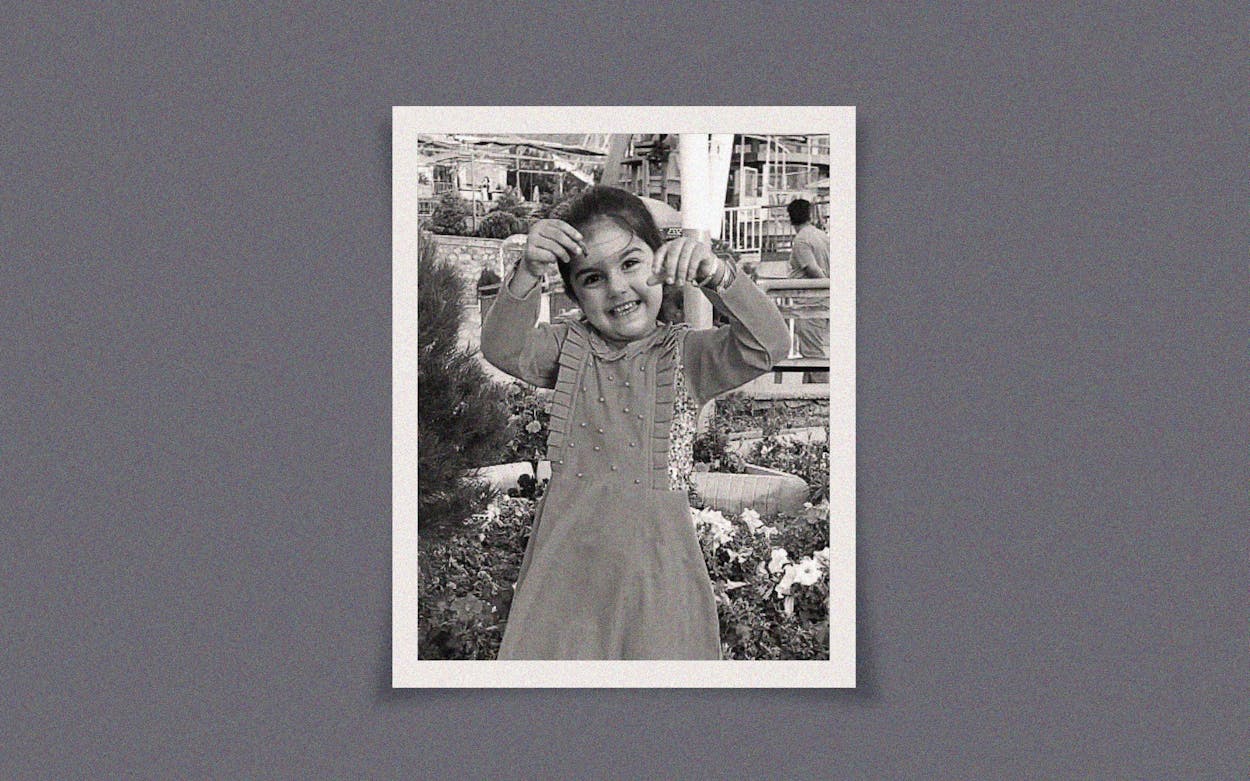

Around 5:30 p.m., however, Zarmeena, who was pregnant with a third child, called, and sounded frantic: she could not find Lina anywhere. The three-year-old had been frolicking in the courtyard pavilion of their apartment complex, near the Medical Center, where a scrum of Afghan kids usually ran around playing. The two-story complex is a maze of narrow footpaths and three-foot stone retaining walls that offer plenty of ways for kids to disappear from any single line of sight; usually there were enough eyes on the courtyard that someone in the community could keep track of the children. But on that day, no one saw what happened to Lina. None of the other kids. No one living in the surrounding apartments. No surveillance camera.

Zarmeena called her husband when it became clear their child was not in any of the usual outdoor spaces. She knew it was one of the shortest days of the year, and it would soon be dark. The family canceled dinner and spent the evening together going door to door in the complex. Maybe, Riaz thought at first, one of the newer families had let her in, unsure who her parents were, and didn’t know how to get in touch. But after they completed their rounds of the complex at around 7:15 p.m., with no sign of Lina, they called the police to report their child missing. At 10:30 p.m., the Texas Department of Public Safety issued an Amber Alert. Many in San Antonio’s Afghan community crackled with panic that night, exchanging texts and messages in a desperate, and ultimately fruitless, search for information.

The Afghan community in San Antonio is small, with a population of around six hundred. Fewer than a quarter are refugees, but many have been trying to help family members get out of Afghanistan following the U.S. military withdrawal. Refugee resettlement agencies in San Antonio help those family members settle into apartment complexes where they can form playgroups and support networks among others who speak their language or come from their region. Many afternoons mothers and children gather in parks, and swing by one another’s apartments unannounced. For the Sardar Khils, it was a near facsimile of life back home in their rural town, with its open-door policies and courtyard playgroups. But when Lina went missing, and days stretched into months, that vision of re-creating life back home was shattered.

“We came here for a good life,” Riaz Sardar Khil told Texas Monthly three months after Lina went missing, his friend Lawang Mangal translating from Pashto. “Now I cannot say this is a safe place for children. Not for me. Not for my family.”

The night Lina disappeared, Pamela Allen saw the Amber Alert on her phone in Boerne, 35 miles northwest of San Antonio. Allen runs Eagles Flight Advocacy and Outreach, a nonprofit that works with immigrants as they settle into the United States and often serves as a pro bono liaison between families in crisis and state agencies such as the police or Child Protective Services. She had experience with missing children cases, and at first thought Lina would be found by the morning at another family’s house.

When she awoke the next morning, however, board members and others she had worked with on past cases called to suggest she offer her services to the Sardar Khils. She contacted the family and was soon a regular fixture at their side. She’s no stranger to intense situations, she said, but what she’s experienced alongside the family the last six months is something new. “I had no idea the craziness that would ensue.”

As the disappearance became news, Afghans around the city began to worry about targeted discrimination. Hessena Sadat, who lives in a different apartment complex across town where many Afghan immigrants reside and didn’t know the Sardar Khils, said the fear was immediate. Even though most of the Afghans in San Antonio are in the country on Special Immigrant Visas, earned based on their service to the U.S. government abroad, they are not always treated like allies. Sadat’s family has been harassed intermittently since they arrived in 2017. She said harassers have banged on their doors late at night, and once even fired guns in the air outside their apartment to intimidate them. “Especially against those who wear a headscarf,” she said, “some people are very biased.” After she saw the Amber Alert, Sadat said, her children and neighbors were scared and wondered if the child been targeted because her family were Afghans, Muslim, or just immigrants in general.

Indeed, almost immediately, theories proliferated on social media, mostly in the comments under each news story about the disappearance, but also in both closed and public Facebook groups dedicated to “finding Lina.” Some speculated that the Sardar Khils were complicit in the disappearance. Parents are always heavily scrutinized by the public in missing persons cases, and law enforcement questioned the Sardar Khils early on. But internet sleuths were more focused on theories based on Islamophobia than on actual leads. They questioned the family’s nationality, spread misinformation about Islam and Afghan culture, and proliferated theories that the couple had trafficked their child, sold her as a child bride, or gotten rid of her because she was not a boy. “There’s definitely a desperation to find the villain here and they’re looking for the easy target,” said Abel Peña, a missing persons private investigator who is assisting the Sardar Khils and worked for 26 years with the FBI.

Tarot readers began posting videos early in the search, offering readings and encouraging viewers to speculate on the case. Several portended death; one claimed one of the other mothers in the complex was responsible. Others devoted less time to mysticism and more to opinion gathering. A YouTube call-in show furthered the Islamophobic theories, and at least one other YouTube livestream began trying to crowdsource information on Allen to implicate her in the disappearance.

In those initial days, Zarmeena’s absence from the cameras struck many amateur sleuths as suspicious. Riaz said he was worried about her being on screen. The Taliban is cracking down on women showing their faces or voices in public media, and even on television dramas. “I have family back in Afghanistan. If they saw that she was in the media it would impact their lives too,” said Riaz.

All the conspiracy theories and Islamophobia has taken a toll, Mangal said. Anyone close to the family has been subject to harassment and speculation, Mangal said. “It’s making their pain more, but not helping.”

Almost immediately after Lina went missing, the San Antonio police called for FBI assistance with their search. Neither SAPD or the FBI would comment on the investigation, as it is officially ongoing. No one aiding the Sardar Khils said they had seen enough evidence to mount any specific theories of who might have taken Lina.

Amid the early Islamophobic reaction, Allen organized an interfaith Christmas Eve prayer vigil to unite San Antonians behind the Sardar Khil family. Elected officials and around two hundred others gathered, from the Afghan community and beyond. Prayers from interfaith clergy were offered in English and Pashto, and Riaz lit a candle as a symbol of hope and faith. Mangal, who sits on the board of the Afghan community council in San Antonio, said his fellow Muslims were happy to join with Jews and Christians to pray for Lina’s safe return. “We have the same pain,” he said, “Our community was thinking, ‘We are not alone.’”

Potential leads brought both terror and hope, Riaz said. The reward offered by the Islamic Center of San Antonio and San Antonio Crime Stoppers San Antonio, an interagency and community crime solving initiative, eventually amounted to $250,000. Tips began to filter in, but most weren’t credible. One tip, however, led to a flurry of action in early 2022. On January 4, the FBI sent a dive team to a pond near the Sardar Khils’ apartment complex, unbeknownst to the family. (The San Antonio Police Department and the FBI would not share the details of what led the FBI to send the team to the pond.)

As word got out and media flocked to the search, someone called Allen to ask if she knew what was going on. She didn’t, and quickly she and Mangal rushed to get Riaz to the pond so that he could hear directly from law enforcement. When they arrived, the divers were surfacing empty-handed. Allen was frustrated at the lack of communication with the family and continues to feel that cultural barriers have gotten in the way. “If they were an American family they would be having that communication,” she said.

When weeks passed without new investigative information being shared with the family, the Sardar Khils and Allen began organizing efforts of their own in late January. Riaz left his well-paying job as a commercial trucker and began driving locally for Amazon, so that he could devote most of his time to the search. The Afghan community and Eagles Flight, Allen’s organization, rallied search parties to comb 27 miles of the nearby Leon Creek Greenway, the type of secluded place where bodies are often disposed. Riaz was always among the searchers, and Allen said she cringed every time he lifted a tarp or once when he unzipped a suitcase. “I couldn’t breathe thinking he might see his baby.”

Soon local psychics and tarot readers also showed up at the searches, and amateur sleuths filmed participants—often to surveil the searchers. Harassment of the family and anyone helping them persisted as volunteers came up empty-handed. Hecklers showed up at the Sardar Khils’ home, followed them in public, and maligned them on the internet. Allen and Mangal too have been harassed, they said, to the point that Allen had to increase security for herself, her mother, and her adult son with special needs.

But more heartening was the diversity of people who came out for those long days of searching on the greenway, Allen said, including families who knew the search process all too well. One of her former clients, a teenage girl with a disability who had been abducted and recovered early in the pandemic, approached Riaz around noon of one search day. “Don’t give up,” she told Riaz. “My parents didn’t give up, and they found me.”

The search continued for eight weeks, until volunteers had walked the entire greenway. The conclusion was “bittersweet,” Eagles Flight posted on Facebook: while the family was relieved not to find the worst, finding nothing was maddening in a different way.

Missing persons files are retained “indefinitely,” according to the FBI, and SAPD told local media that missing persons cases are never considered closed until the person is found. But as time goes on, the police department said, the flow of information coming in determines activity on a case. Recently, reliable information and leads on Lina have been scant, producing little for investigators to look into. It’s chilling, as 94 percent of missing children are found within 72 hours, while the outlook in the days, months, and years beyond that are much bleaker. Yet, with no body having been discovered, Allen believes Lina was kidnapped, not killed. “I absolutely feel that someone is holding her,” she said.

On June 10, nearly six months after Lina’s disappearance, Zarmeena gave birth to a baby boy, Saud. It’s an optimistic name, meaning “fortunate” or “prosperous,” expressing the aspirations any parents would have for their child. The Sardar Khils have been excited to welcome a new member of their family, and have placed one foot firmly into the future they look ahead to. But their other foot is still firmly planted in the past, on December 20, the last time their family was truly whole. They say they still want to see more from law enforcement, but in the absence of information, they remain hopeful. It’s all, Riaz said, that they can do.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Refugees

- San Antonio