Working in the Texas Capitol is not for the faint of heart. Convening for just a few months every two years—for a regular January-to-May session and sometimes a few special sessions through the summer—the Legislature can foster an intense and punishing environment. Pay is low, stakes are high, and drinking on the job is prevalent. Under the circumstances, it’s not uncommon for staff members to call it quits after just one session. As a Capitol staffer told me, “You can probably ask somebody in mid-April if they like it and if they say yes, they’re probably a lifer. If they say no, you will never see that person again.”

But where is the line between a high-pressure workplace and a toxic one? In some instances, as in the case of former Republican representative Bryan Slaton, who in May was expelled from the Texas House for providing alcohol to his nineteen-year-old legislative aide and then having sex with her while she was intoxicated, the answer was incontrovertible. The House voted unanimously to remove him. In other cases, the boundary is more nebulous. In March, about halfway through the session, the entire full-time staff of representative Jolanda Jones, a Houston Democrat, quit and published a four-page letter that cited an “abusive and hostile” work environment, focusing criticism on a romantic relationship between Jones’s 31-year-old son and her 26-year-old staff intern that the letter called “inappropriate.” The House General Investigating Committee (GIC), a five-member group that initiates inquiries into such complaints, announced an investigation into Jones’s workplace conduct. “I welcome that investigation and look forward to being vindicated of any wrong doing [sic],” Jones wrote in a statement she issued in response. The committee has issued no further statements on the matter and Jones remains in office.

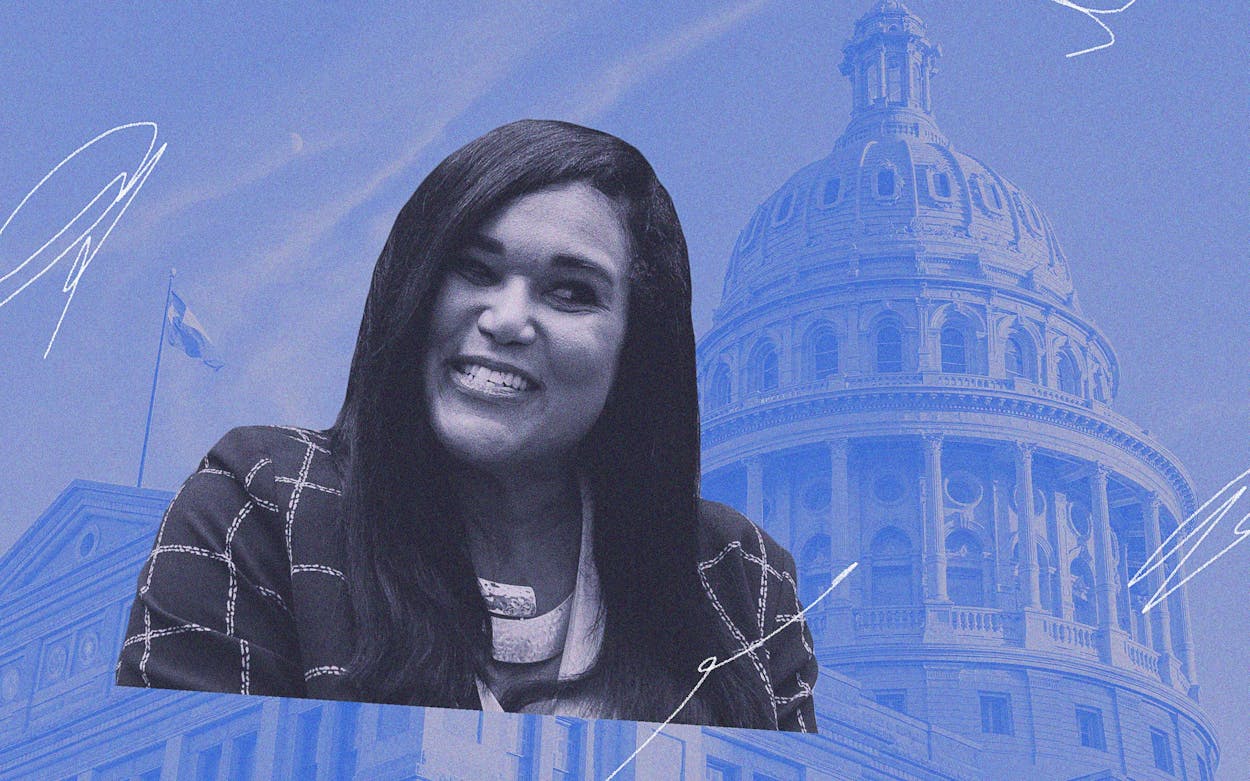

And then there’s the flowerpot incident, a story nearly every lawmaker with whom I talked during this session had heard some version of. In March 2021, representative Shawn Thierry, a Democrat from Houston then serving her third term, had two small, decorative flowerpots delivered to her office. According to D. Powell, Thierry’s former legislative director and senior policy analyst, who for privacy asked that her first name not be published, Thierry was displeased that staffers did not immediately inform her of the flowerpots’ arrival. She began to yell, multiple former staffers say, and then, according to Yisel Covarrubias, her then–legislative assistant, Thierry threw the pots across the room, aiming one at her. “She always wanted to know everything that happened as soon as it happened—every phone call, every email, every person who came into the office, every letter,” Powell, who was sitting outside the interior office and recalled hearing the pots shatter, said. “I don’t know what about the flowerpots in particular was so inciting.”

Thierry denies she threw the flowerpots at staffers and says that she simply dropped them and they broke on the floor. “I’ve heard that allegation before,” she told me, calling it “patently false.”

A group of four of Thierry’s aides reported the incident, along with a few other complaints, to the House GIC and resigned on May 2, 2021. In a letter, the staffers asked the committee to investigate Thierry in confidentiality, “as we have concerns about retaliation or reprisal from our harasser.”

Though rumors of the allegations spread across the Capitol, staffers say the General Investigating Committee ultimately did not act on their complaint or even interview them about it. But this session, after Capitol insiders not associated with the office began circulating rumors about the incident on social media, some of Thierry’s former staffers—none of whom still work in the Legislature—came forward to tell Texas Monthly about their experiences working in Thierry’s office.

Apart from the flowerpot incident, most of what Covarrubias and two other former staffers who spoke to Texas Monthly described occurring in Thierry’s office ranged from extreme micromanagement to daily invectives. Covarrubias said Thierry’s office was “the most abusive environment I’ve ever worked in.”

Some said the pressure was so high that their mental health deteriorated. Covarrubias recalled that a fellow staff member suffered anxiety attacks on a couple of occasions, including once when Covarrubias found her curled up under her desk in the fetal position. Another former staffer who declined to be named said that a stressed-out coworker “lost so much weight over the course of three months, she needed me to help her safety-pin her skirt.”

Like many aides in the Capitol, Thierry’s staffers were expected to work exceptionally long hours throughout the session. In most cases those late hours are required for urgent legislative business. But in Thierry’s office, on one occasion, staffers alleged in their complaint, she made staff stay past two in the morning to redecorate. Employees also say their boss demanded that “Team Thierry” be present at all times when she was in the office, even late at night, regardless of whether they had pressing tasks to accomplish. For a time, the representative had staff members account in writing in five-minute intervals for every single action they took, said Powell. The demands became so overbearing, some staffers say, that they were afraid to even step out to use the bathroom.

Of course, most Capitol job listings specify that candidates “work a flexible schedule including long hours, nights, and weekends.” As Thierry put it, “it’s part of the job.” Thierry also denied each specific allegation levied by staffers against her. She said she never demanded that they record how they used their time, nor did she prohibit them from using the bathroom. “The bathroom was right at the end of the hallway,” she said. “Of course they can go to the bathroom.”

But Thierry’s office has had high staff turnover, even by the standards of the Legislature. Powell, who had earlier worked as Thierry’s intern, said that in the courses of the Eighty-sixth and Eighty-seventh Legislative Sessions, she saw some twenty staffers come and go. According to staff rosters, of those who worked for Thierry during her first session, in 2017, none stayed for her second session, and Powell was her only employee who stayed between the second and third sessions. None of her staff stayed on between her third session and her fourth, this year. Indeed, many of Thierry’s Democratic colleagues are aware of her reputation with staff, with one representative telling me her behavior was “an embarrassment to the caucus.”

Thierry, who denied she had struggled to retain staff and cited one staffer who left after the 2019 session but returned this year as her chief of staff, had a theory for why some had come forward with allegations of abuse. She said her accusers were retaliating for her vote this spring in favor of Senate Bill 14, legislation now signed into law that will prohibit Texans younger than eighteen from accessing gender-affirming care. Almost the entire Democratic caucus voted against the bill, but Thierry publicly announced her support in a long speech on the House floor.

“I’m not surprised,” Thierry said of the allegations, identifying specific staffers she thought might be surfacing them, some of whose names Texas Monthly is redacting to protect their privacy. “I mean, [redacted] is gay. Yisel was bisexual. I think [redacted] may have been bisexual. I think [redacted] told a consultant that came into the office that she was bisexual.” She added, “I really just feel a lot of this is retaliatory for my vote on SB 14.”

Two years before that vote, on the same day they resigned, Covarrubias, Powell, and two others submitted their formal complaint to the House GIC. They say leaders of the committee never got back to them, as they are required to do by House rules. Nearly a month after they had sent the original complaint, one of Powell’s coworkers requested a status update, and the group was sent a new complaint form they were told to complete if they wanted to pursue further action. “To the best of my knowledge, the initial complaint satisfied the GIC complaint rules,” Powell said. She added, “At this point, I chose not to complete the form, as I was already in the process of moving out of state.”

Former representative Matt Krause, who chaired the House GIC last session; Darren Keyes, who served as clerk then; and 2021 committee member representative Stephanie Klick did not respond to requests for an interview. Representative Andrew Murr, who chairs the committee this session, declined Texas Monthly‘s request for an interview.

Slaton’s expulsion from office this session, the first time a member was ousted since 1927, provided some former Thierry staffers with hope that workplace-culture issues might be taken more seriously at the Lege now. Others, however, thought the Slaton response was an exception to the rule. One issue is that there are few resources available to employees who feel they’ve been mistreated other than the GIC. “There’s no HR,” Covarrubias said. “There was no one we could go to to help talk about what was happening.”

Cait Wittman, the communications director for House Speaker Dade Phelan, told me that members are given complete authority over all personnel actions in their offices. “As the employing authority for their respective staff, members are responsible for ensuring compliance with applicable personnel policies and procedures,” she said. That means that even though they collectively function within the institution of the Texas state legislature, each member’s office operates independently from the whole. Members have the power to determine their staffs’ salaries.

Where hostile workplace issues are concerned, Wittman said, staffers “have a couple of options.” They can seek out their employing authority—that is, their member—which in the Thierry case was not an option. The next step is going to the House Administration to seek informal resolution or to the House General Investigating Committee to file a formal complaint.

“I wouldn’t have known what the recourse was to file an official complaint,” one former legislative staffer, who didn’t work for Thierry, told me. What’s more, taking formal measures poses risks. “Are you creating a problem for the next person you work for?” she said. “Are you bringing that baggage to another elected official? Is your former boss going to get mad at your new boss? Are they going to retaliate? Are they going to say bad things about you to everyone?”

The staffer cited the Jolanda Jones incident as an example of how reporting hostile workplace behavior can cause backlash. After Jones’s staff resigned, Jones remarked in a statement that working at the Texas Lege is a “demanding job” and that some of her staff “decided this job is not for them,” suggesting they couldn’t cut it in a tough work environment and potentially harming their chances of being hired in the future. “I think people are trying different things but they’re always going to get attacked, no matter whatever mechanism they use to try to stop this behavior,” the staffer said.

Others echoed that sentiment. Powell said that her understanding of harassment claims—not just in the House, but in Texas more broadly—was that there was often a stigma attached to those who bring them and that the claims were often not addressed. “It was a feeling that I had, and the feeling came to fruition,” Powell said.

Covarrubias, who now works as a paralegal in a personal injury law firm, maintains that her career at the Lege was spoiled by her experience with Thierry. “The thing about the Capitol is that if you share what happened in an office, it is common knowledge that you get blacklisted,” she said. “You can’t return to work for another member. And as someone who loves the work,” she added, starting to cry, “that really terrified me because I’m a first-generation daughter of immigrants. It took a lot to build the relationships, the credibility to have my name in that building.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Lege

- Houston