John Henry Ramirez doesn’t want to be executed, though he knows why a lot of Texans—including the state attorney general and the head of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ)—wish him dead. One night in July 2004, Ramirez, high on cocaine, marijuana, and vodka, drove around Corpus Christi to find someone to rob so he could buy more drugs. He saw Pablo Castro emptying the trash outside the convenience store where he worked. Ramirez stabbed Castro, a 45-year-old father of nine, 29 times, and went through his pockets, stealing $1.25. Castro died, and Ramirez was caught, found guilty of capital murder, and sentenced to die.

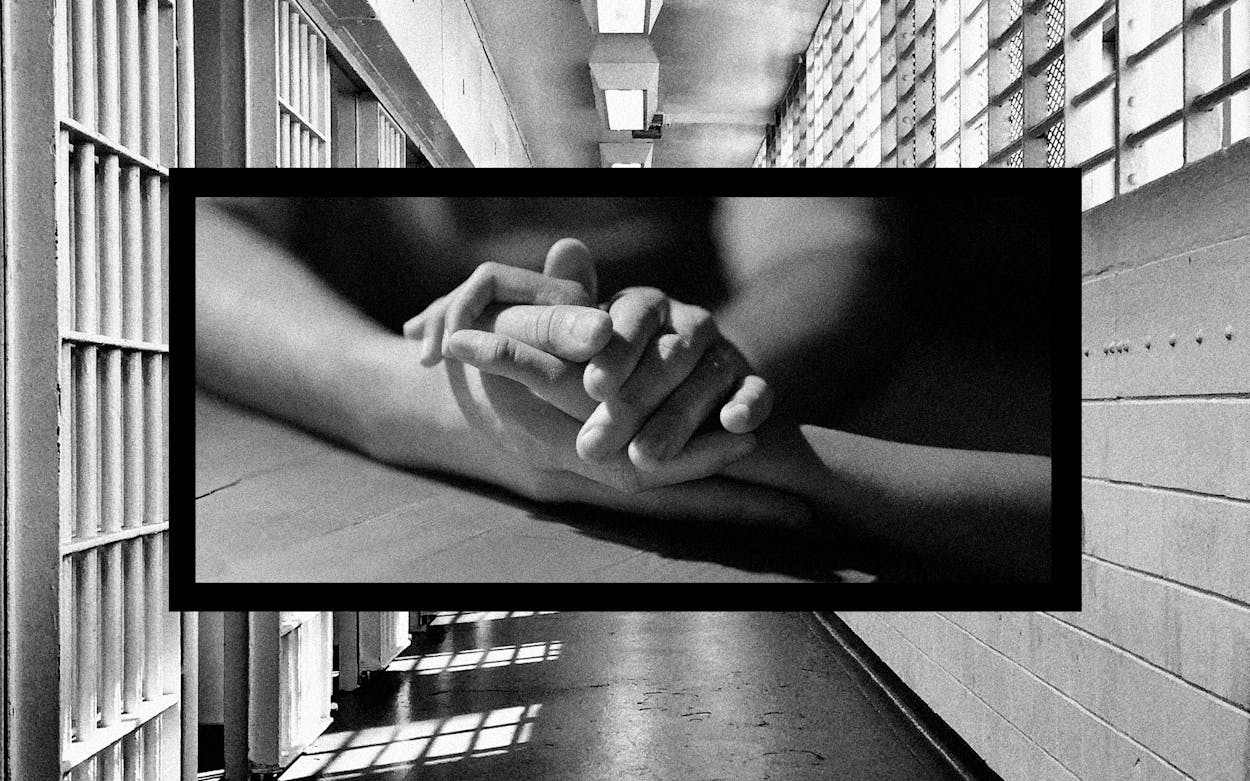

Ramirez, now 37, has never claimed innocence. At his 2008 trial he admitted to the murder, and during the punishment phase he instructed his lawyers to stop trying to save him and just read Psalm 51:3 aloud: “For I acknowledge my transgressions and my sin is ever before me.” Today he knows he is destined to die. All Ramirez wants is for his spiritual adviser, Dana Moore, the senior pastor at Second Baptist Church in Corpus Christi, whom he met on death row in 2016, to be at his side when he meets his maker. Ramirez wants Moore to be able to touch him and pray aloud with him. But this summer, the State of Texas denied Ramirez’s request and prepared to execute him. He appealed the decision and, on September 8, when he was scheduled to die, the U. S. Supreme Court stopped the execution until it formally ruled on a question that has vexed the body for several years: Just what do we owe those we have condemned to die at the moment of their deaths?

Ramirez doesn’t think he’s asking for too much. In fact, for almost four decades, Texas allowed ministers into the execution chamber to do exactly what he is requesting. Beginning in 1982, when Texas resumed the execution of inmates with the okay from the Supreme Court (which had ruled capital punishment unconstitutional a decade earlier), the TDCJ allowed state-employed ministers to be present in the death chamber—and they prayed aloud with the condemned and laid hands on them as part of their work. Reverend Carroll Pickett, the TDCJ chaplain from 1980 to 1995, stood by 95 of the condemned as they died and usually put his hand on their right leg. His successor, Jim Brazzil, did the same, just below the knee. “I usually give ’em a squeeze,” he said in 2000, to “let ’em know I’m right there.” Texas has executed 573 convicts since 1982 and never once had a disruption caused by a minister—a testament to the efficiency and control of the people who run the system.

But everything changed in February 2019, when condemned inmate Patrick Murphy asked for a Buddhist spiritual adviser in the execution chamber—and TDCJ, which employed only Christian and Muslim chaplains, said no. Murphy was granted a stay by the Supreme Court, which ruled a month later that it was up to the states to decide who could be in the execution chamber, but they couldn’t discriminate on the basis of denomination. Texas chose the route of least resistance: although it would allow in the viewing room spiritual advisers of all faiths (whether employed by the state or not), none could go in the execution chamber.

In June 2020 Ruben Gutierrez, convicted of a 1998 murder, tested the new protocol when he filed for a stay because he wanted his non-TDCJ pastor with him. The U.S. Supreme Court granted it and in April 2021, TDCJ changed its policy again, allowing ministers into the chamber again, though now they had to have a background check and go through a staff orientation. The policy didn’t say anything about restrictions on pastors’ touching or praying, but when Ramirez’s attorneys asked about both, they were told neither would be allowed: Moore could stand in the chamber with Ramirez but couldn’t pray out loud or lay hands on him.

After the U.S. Supreme Court stayed Ramirez’s execution in September, it granted him a writ of certiorari, meaning the full body would review his case on the merits. The issue comes down to two implacable social ideals: religious freedom versus law and order. For Ramirez, having Moore by his side in the chamber is a matter of being allowed to practice his faith, something guaranteed by the federal Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, a 2000 law that prevents prisons from placing a burden on “any exercise of religion” by inmates. A ban on touching and praying, wrote Ramirez’s lawyer Seth Kretzer in a brief, would turn the execution chamber into a “godless vacuum.”

For the State of Texas, the issue is security, not God—though in its briefs, the state has questioned the sincerity of Ramirez’s beliefs and accused him of filing motions to delay the inevitable. According to the state, the very nature of prisons requires that some religious behavior will be limited in the name of security, and bringing in a non-TDCJ chaplain is too big a risk, especially when it comes to laying on hands. As the state wrote in one of its briefs, “An outsider touching the inmate during lethal injection poses an unacceptable risk to the security, integrity, and solemnity of the execution.” The brief goes on to note potential trouble in the chamber, citing “inadvertent interference with the IV lines” and saying that “vocalizing during the lethal injection would interfere with the drug team’s ability to monitor and respond to unexpected occurrences.”

On Tuesday, the two sides met for oral arguments at the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. The stakes of the hearings were high for both Texas and the nation. Texas would like to start executing inmates again, but executions in the state have ground to a halt as state courts wait to see what the high court says about the issue. (Four other Texas inmates slated to die this fall had their executions stopped on similar religious-freedom grounds.) The Ramirez case also gives the court the chance to make a ruling that will be binding across the country after several years of hearing death row religious freedom cases in a piecemeal and sometimes contradictory fashion.

Almost immediately, the justices signaled where they stood on the issue. Clarence Thomas questioned the sincerity of Ramirez’s religious beliefs. Brett Kavanaugh challenged Kretzer numerous times about the risk that an outsider chaplain in the execution chamber could cause. Samuel Alito speculated that a flood of new cases would hit the court’s docket if it ruled in Ramirez’s favor. “What’s going to happen when the next prisoner says that I have a religious belief that he should touch my knee?” he asked Kretzer. Only liberal justice Sonia Sotomayor expressed much sympathy for Ramirez’s wish to have his pastor next to him.

Outside the Supreme Court, on a stone bench in a shaded area, sat Dana Moore, who had flown from Corpus Christi to hear the arguments over a set of outdoor speakers. The mild-mannered, silver-haired preacher smiled when he heard his name mentioned by the justices but didn’t like it when they questioned Ramirez’s sincerity. “I understand their line of questioning,” he said later, “but with John, the sincerity is there—it has been there for several years. He and I talked about it. ‘Why can’t I hold your hand? Why can’t I hold your foot?’ That’s it, that’s the whole point, a little thing like that.”

Touch, Moore said, is a huge part of his ministry, whether he’s holding hands at Bible study or ministering to a dying congregant in a hospital—where, if he can’t hold a hand, he’ll touch a forehead or even a foot. “It’s not written in doctrine, it’s just what we do. It’s a sign of encouragement, fellowship, peace, love, acceptance. It has a calming effect.”

After the arguments, Moore said he was impressed by Kretzer’s performance in front of the court and thought things looked promising. “I’m not a legal expert, but I think it went well for John.”

Douglas Laycock, a former law professor at the University of Texas, who has argued before the Supreme Court five times and is one of the country’s top authorities on the law of religious liberty, isn’t so sure. Laycock filed an amicus brief with a dozen other law professors urging the court to allow Moore in the execution chamber unencumbered by rules on touching and praying. (Dozens of officials and religious and political groups, some of them conservative, also filed briefs in support of Ramirez; the right-wing First Liberty Institute wrote, “Government failure to allow for the exercise of an individual’s sincerely held religious beliefs threatens religious individuals’ fundamental rights as protected by the Constitution and as intended by Congress.”) Laycock, though, doesn’t expect the court to rule in Ramirez’s favor. “All the justices support the right to free exercise of liberty,” he said, “but each has other things he or she cares about more. Liberals care more about gay rights, so that trumps religious liberty. Conservatives care more about accelerating capital punishment—so that trumps religious liberty. I think they want to get Ramirez executed as quickly as possible.” Laycock predicts the court will rule against Ramirez 6–3, along partisan lines.

For his part, Moore doesn’t think the state’s refusal to allow him to minister to a dying man speaks well for us as a society. He references Matthew 25:40, Jesus’s call for compassion for the poor, strangers, and the imprisoned: Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me. “When Jesus talks about the least in society,” he said, “it’s difficult to find someone lesser than those who are on death row.”

What do we owe those we’ve condemned to death? For Moore, it’s simple: treat them as human beings, not monsters. “Every person is made in the image of God,” he said. “We don’t lose that by our actions. John was made in the image of God.” He’s convinced Ramirez will go to heaven upon his death. “He’s already received saving grace—his eternity is set in Christ, because of God’s grace through John’s faith.”

Moore has never touched Ramirez—they have only seen each other through plexiglass in the visiting room at death row. If the pastor finally gets the chance, it will be during his friend’s last moments on earth. But in that moment, Moore knows, all of his work will have been worth it.

- More About:

- Supreme Court

- Death Penalty