The nation is beset by dangerous radicals, according to those who lead the Republican Party of Texas. But some are more dangerous than others. To see the face of radicalism in Texas today—to bear witness to a truly dangerous and seditious man—skip over the purple-haired anarcho-communists of Deep Ellum and Montrose. Turn instead to Palo Pinto County, an hour west of Fort Worth, and the frightening visage, if you can bear it, of Glenn Rogers, representative for Texas House District 60.

Rogers doesn’t look particularly dangerous: He’s a bespectacled, Texas A&M University–trained rural veterinarian and sixth-generation rancher with a shock of salt-and-pepper hair and a cowboy hat to match. He owns land on the Brazos River, which he surveys, through transition lenses, from his Ford F-350. His politics are conservative—pro–border wall, antiabortion, anti–gun control—and his brow seems perpetually furrowed. In the family of man, Rogers comes from the Hank Hill branch.

But looks can be deceiving. Since 2020 Rogers has been making unaccountable decisions. He ran that year for a state House seat against Jon Francis, son-in-law of Farris Wilks (of Cisco, east of Abilene). Farris and his brother Dan Wilks are prodigious GOP funders and ideologues who hail from one of the furthest-right wings of the party. They could be called Christian nationalists—if they didn’t adhere to a religion invented by their father and grandfather (who were thrown out of the local Church of Christ).

They’d heaped millions of dollars upon many state representatives with whom they had no familial relationship, and here was Rogers going against their kin. He was heavily outraised yet he won, just barely, by 677 votes out of about 23,000 cast. He was boosted by the endorsements of former governor Rick Perry, who has been known to help out a fellow Aggie, and Governor Greg Abbott. But Rogers now had a target on his back, and he won renomination in 2022 by an even smaller margin—beating conservative activist Mike Olcott by 318 votes, out of about 20,000 cast.

In the 2023 session, Rogers was on notice. By the unofficial laws of Texas politics, he should veer to the right and otherwise avoid attracting negative attention. He didn’t. When the House impeached Attorney General Ken Paxton, Rogers joined the majority of the Republican caucus to vote in favor of the move. And when Abbott pushed hard for his voucher program—which would divert funding from public schools to private ones—dragging the House into two miserable special sessions in which he promised retribution unless representatives such as Rogers went along, Rogers refused to bend. He became one of 21 rural and small-town Republicans who said the proposal would permanently weaken the Texas public school system on which their communities depend. Meanwhile, he wrote an op-ed in the Mineral Wells Area News criticizing far-right activists in his district for their associations with further-right figures who consort with white supremacist Nick Fuentes.

In the case of the voucher bill, Rogers arguably was following former House Speaker Pete Laney’s old-fashioned advice to “vote your district,” placing the needs and preferences of constituents ahead of ideological questions or political expediency. But there’s little room for that sort of independence in today’s state GOP, whose leaders regularly champion policy positions dear to the far-right 3 percent of Texans who decide Republican primary elections, even when that puts those leaders at odds not only with the majority of voters but with what the majority of Republicans tell pollsters they want. Regarding the impeachment, Rogers said he voted against fellow Republican Paxton simply because, after considering the abundant evidence of the attorney general’s corruption, he believed it to be “the right thing to do.” But it all came at a cost. This year, his old rival Olcott is running again, and Rogers has powerful enemies aligned against him.

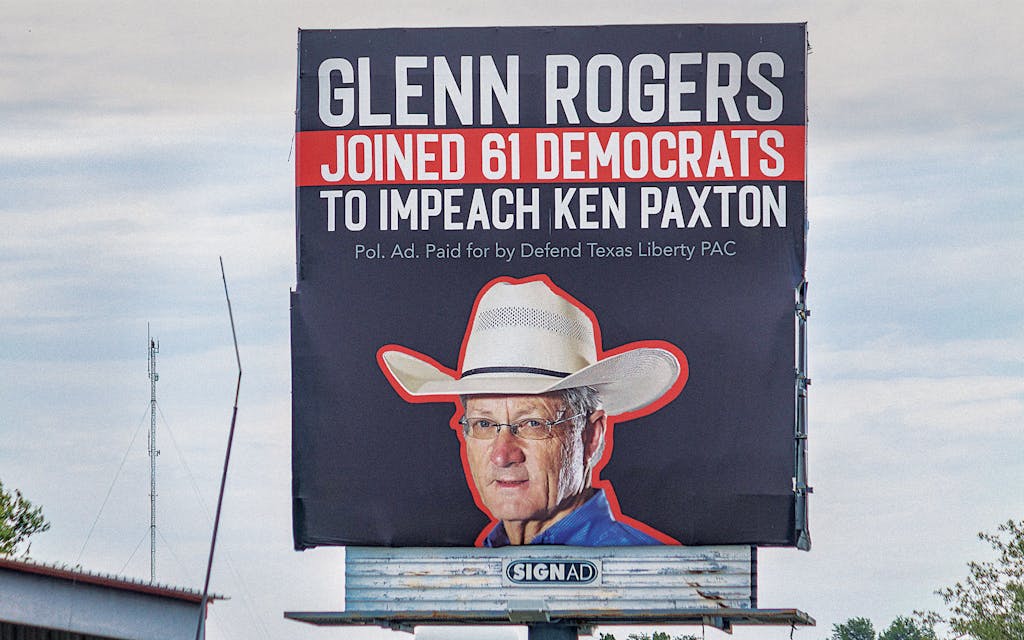

Defend Texas Liberty PAC, largely funded by the Wilks brothers and Midland oilman Tim Dunn, put up billboards in Rogers’s district last year slamming his impeachment vote—even as the PAC was, by all appearances, lobbying for Paxton’s acquittal in the Senate trial by giving its presiding judge, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, $3 million in loans and donations. Paxton has endorsed Olcott. So has Greg Abbott, Rogers’s onetime benefactor. So has Ted Cruz (long funded by the Wilks brothers); Ted’s father, Rafael (an evangelical pastor); agriculture commissioner Sid Miller; state party chairman Matt Rinaldi (who has worked as an attorney for Farris Wilks); former party chairman Allen West; and a long list of notable statewide right-wing activists. At the end of the year, as the primary season was beginning to ramp up, Rogers’s campaign had just $70,000 on hand compared with Olcott’s $210,000.

It would be a minor miracle if Rogers can once again skate through. But he isn’t going quietly. In December, Miller posted a picture of himself holding a shotgun with the warning that he was on a “RINO [Republican in Name Only] hunt,” on his way to “tak[e] back the Texas GOP from the double dealers, the backstabbers, the liberals, and the teachers’ union shills!” He means folks like Rogers, who appears to have texted Miller—per screenshots posted by Miller on X—to up the ante. “If you had any honor, you would challenge me, or any of my Republican colleagues to a duel instead of strutting around posting pictures with a rifle threatening to shoot

RINOS. A RINO is any conservative Republican not bought and paid for by Wilks and Dunn. You are an embarrassment to agriculture and the State of Texas.”

For a backbench lawmaker, the easiest way to stay in office is to do what powerful Texans—the governor, the party, the lobbyists, right-wing billionaires—tell you to do. If you don’t, you get punished and sometimes banished. House Republicans in the Eighty-eighth Legislature told influential figures, on several notable occasions, to get bent. This March those influential figures will try to punish these GOP apostates. If they succeed, the House will become more compliant, more docile. It will be even less likely to try to hold Republicans accountable for criminal activity and other wrongdoing. It would accede more often to the governor and lieutenant governor’s priorities, first among them school vouchers.

For the past fifteen years or so, the GOP primaries for the Texas House have been virtually the only elections that matter in Texas. Almost none of the 38 congressional or 31 state Senate districts are really competitive in the general election; races for statewide office are very rarely competitive. As far as Texas democracy goes, the House has become a load-bearing institution. Only the lower chamber engenders the back-and-forth debate, negotiation, and compromise that we’ve long associated with what we call politics.

Over those fifteen years, more-centrist conservatives have fought the far right for control of the House. The struggle has resembled trench warfare. Much has been hypothetically at stake, but the contest has been defined by numbing futility. Vast riches have been wasted and a few lives ruined in the Republican primaries, only for the two factions to go back to work in Austin in roughly the same numbers. Dulce et decorum est, said the consultant on his way to cash a check from a losing candidate who laid down his career and his marriage for some Permian plutocrat or Texans for Lawsuit Reform.

The House was conservative to start with and has drifted further right in recent years. That’s not because right-wing donors, such as Dunn and the Wilks brothers, have succeeded at the ballot box—their candidates often lose. The cumulative pressure of many years of primary challenges has brought the chamber more in line with the activist base than it has been in a long time. Ordinary turnover plays a role too. The House seems like a more unhappy workplace than it used to be, and some of the better members eventually hit eject. Former House Speaker Joe Straus did, in 2019. This year’s crop of retiring moderate Republicans includes Kyle Kacal, of College Station, and Andrew Murr, of Junction, who led the impeachment of Paxton. Murr pointed to the toll his time in public service had taken on his family as a reason for quitting.

What’s different this election year is the number of interested parties trying to put their stamp on the House—to extract from it some measure of loyalty or dependency going into the 2025 legislative session. Confusingly, these crusades, by Abbott and Paxton and Dunn and the Wilks brothers and the rest, don’t always overlap in the way they have against poor Glenn Rogers. All the crusaders are trying to elect friends and beat back perceived enemies, but their level of commitment across their supported candidates varies wildly, and sometimes they’re fighting with one another. To track all the conflicting agendas, you need a bulletin board, a stack of mug shots, and some string, like Matthew McConaughey in True Detective. Maybe also, for good measure, a case of Lone Star.

The Texas GOP is under the leadership of former state representative Matt Rinaldi, a long-ago-purchased princeling of Dunn, the Wilks brothers, and Dallas hotel magnate Monty Bennett. Rinaldi is a veteran of the civil war against Straus, when he was Speaker from 2009 to 2019. The GOP chairman, in line with his owners, hates current Speaker Dade Phelan and House leadership more generally, and most often cites Phelan’s willingness to appoint Democrats as committee chairs—a common practice in the House as long as Republicans have held the chamber, even under Straus’s right-wing predecessor, Tom Craddick—as the reason. Rinaldi is supporting Phelan’s primary opponent, David Covey, in Beaumont, and the party is supporting anti-Phelan candidates in other ways and other places.

Paxton says he wants retribution for his impeachment, and he has endorsed challengers of several House impeachment managers. But mostly he’s put his special imprint on the folks that his backers are supporting anyway. Like Rinaldi, Paxton is a veteran of the House civil war, supported for most of his colorful career by the likes of Dunn and the Wilks brothers. Paxton once ran against Straus for the speakership but withdrew just before the vote, when a straw poll in the Republican caucus showed he was about to lose. He’s supporting candidates such as Devvie Duke, a local Republican activist running to replace the retiring Charles “Doc” Anderson, in Waco. Duke is backed by tea party–descended activist groups and has the same supporters as Paxton. For this open seat, Abbott is supporting Duke’s challenger, Pat Curry, a businessman who touts his experience in the trucking industry.

While Rinaldi and Paxton are empire building, others are making more surgical interventions. Somehow state representative DeWayne Burns, a mildly independent Republican investment manager from Cleburne, south of Fort Worth, earned the kind of enmity from Dan Patrick that led the lieutenant governor to endorse Burns’s challenger, Helen Kerwin, the former mayor of Glen Rose. (The Speaker and the lieutenant governor typically don’t endorse candidates in each other’s chambers.) And Rick Perry, back in Texas with time to kill, has endorsed a variety of candidates who support House leadership. He’s the only Republican grandee to endorse Dade Phelan over his generally unremarkable challengers.

Abbott has threatened to single out opponents of his school voucher bill for special ministrations of justice. But if his more general plan is to build prestige for the governor’s office—to win influence in the House next session—his vengeance crusade poses a problem. His endorsement, plus a lot of money, is probably not enough for his candidate to win in many of the districts held by apostate Republicans. At the beginning of this year, challengers had more cash on hand than incumbents in only three of those sixteen districts. One incumbent, the well-connected Charlie Geren, of Lake Worth, friend to many Austin lobbyists, had a more than 455-to-1 cash advantage over his opponent, Jack Reynolds, a former part-time economics professor in Tarrant County, who reported a little more than $2,000 in his campaign account.

Abbott has been doing something notably different from what he pledged to do. He has strongly backed several of the Republican House impeachment managers from the Paxton trial, among them Briscoe Cain, of Deer Park, east of Houston, and Jeff Leach, of Plano, just north of Dallas. Abbott has also thrown his weight behind incumbents who have been generally supportive of House leadership, including Kronda Thimesch, cofounder of a landscaping company from Denton County, just north of Fort Worth. While Paxton and those who bankroll him seek to overhaul the House, Abbott just wants a cheering section in it—and is willing to obtain one by helping to reinforce the status quo.

In Deer Park, Abbott endorsed Cain at Battleground Golf Course, to a roomful of cheering fans. Cain was a stalwart soldier of Abbott’s voucher plan during the session, and he’ll no doubt support the governor next year. But Cain is a living example of how hard it can be to carve out spheres of influence in the House. He was elected as part of the Dunn-and-Wilks faction. He was a right-wing troublemaker whose deskmate on the House floor was the legendary troll Jonathan Stickland.

But then Cain moderated. He got co-opted. Woke, his old friends might say. He voted to impeach Paxton and served as an impeachment manager. He is a stalwart supporter of Phelan. His allegiance has shifted.

Abbott’s happy to have him. The governor delivered a fumbling endorsement speech in front of Cain’s five children, who were visibly bored to death and squirming. They didn’t fall far from the tree: in time Cain started to look a little bored too. (His wife, Bergundi, dutifully continued nodding.) Abbott briefly mentioned the voucher fight, then spent the next five minutes outlining his recent actions on the border, the brave stands he’s taken, and the cowardly actions with which Biden has responded. He accused the president of “traitorship.”

At some point, it seems, he remembered Cain. Referring back to his own long list of accomplishments, Abbott said, “I can’t do stuff like this on my own. That’s why I’m here today, because I need Briscoe Cain back with me in the Texas House of Representatives.” This was perplexing, because most of what Abbott had described he could and did do on his own—his border standoff needs no help from lawmakers. Abbott hasn’t identified anything he needs Cain to do or anything that Cain has done.

But perhaps, at this advanced stage of his governorship, it is enough to have a man in Deer Park who calls himself the governor’s friend. Men like Glenn Rogers will buck and fight, and they may even duel you. Briscoe Cain requires little care and feeding, and he’ll come when you call.

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “House Hunters.” Subscribe today.