This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

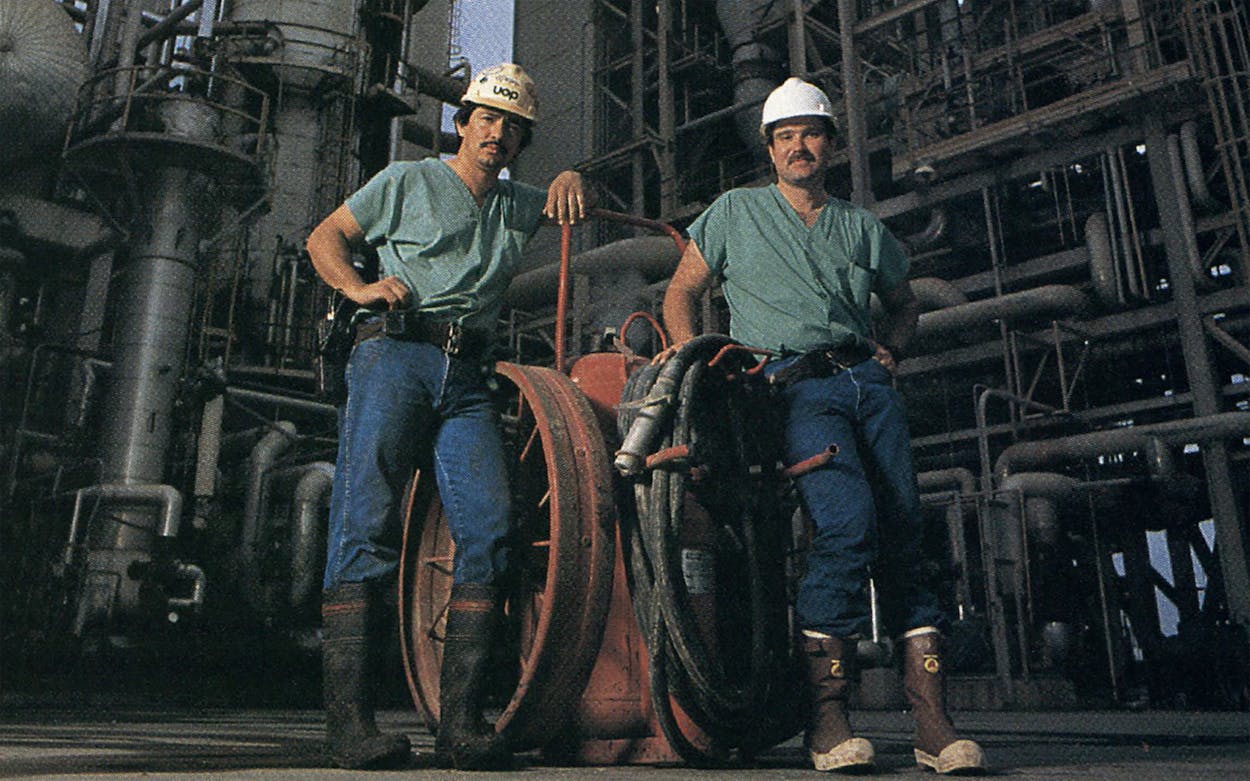

It isn’t difficult to find the Diamond Shamrock petroleum refinery in Three Rivers. As you approach the small South Texas town, the horizon is dotted with tall, brownish furnaces and miles of steel piping. A sour smell hangs in the air, although the old-timers who work at the refinery insist they don’t smell a thing. Neither, apparently, do the thousands of pigeons that roost happily on $200 million worth of hardware. The refinery looks like an adult version of a child’s Lego set, including rhythmic hissing and clanking. The critical moment occurs when the vaporized oil rises into the tall stacks and mixes with a yellow powdery catalyst, and two seconds later—presto—gasoline is swirling around in the warren of connected pipes.

“Making gasoline is like building a cake—you have to follow the recipe and keep a sharp eye on your ingredients,” said Dewey Mark, Diamond Shamrock’s grizzly-voiced, cigar-chewing executive vice president, who oversees the production of 4.2 million gallons of gasoline per day at the Three Rivers refinery and at a larger one near Dumas in the Texas Panhandle.

Mark is not a happy baker. His two refineries are running night and day at capacity, turning out gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel seven days a week, yet his company is hardly earning enough money to pay the overhead. In 1987 Diamond Shamrock, which refines crude oil and sells gasoline at two thousand stations in the Southwest, earned only $1.6 million on revenues of $1.7 billion.

Mark’s dilemma illustrates the fundamental problem facing petroleum refineries in Texas. Prices for the products they sell—gasoline and jet fuel, for instance—have fallen even faster than the price of crude. The difference between the price of crude oil and the price of an equivalent amount of product sold has fallen from an average of $5 in 1985 to a low of $1.50 in 1987. (Petrochemical refineries, however, are enjoying fat profits because of increased demand for such products as plastics.) Mark estimates that most Gulf Coast gasoline refineries are living on a $2.50 to $3.50 difference, higher than in 1987 but still not enough to satisfy the expectations of shareholders.

What hurts Texas refineries even more than supply-and-demand economics is the volatility of the price of crude oil. Like oilmen, Mark feels the frustration of being in the grip of economic forces he cannot control. Bulk purchasers of gasoline—marketers and speculators—see the price of crude futures falling and postpone buying gasoline in the expectation of getting a better deal. Refineries, in effect, have to buy high and sell low, causing profit margins to get squeezed.

Also like oilmen, refiners are paying the price of rising expectations during the boom. When oil prices were high, many of the major oil companies spent millions of dollars upgrading their refineries to use a cheaper grade of high-sulphur oil known as sour crude. When the price of oil dropped, the huge price differential between sweet and sour crude vanished. In the long run, the investment in high-tech refineries may pay off, but for now it is wasted; sour crude doesn’t yield as much gasoline.

In addition to oil prices, the other shadow hanging over Texas refiners is foreign invasion. Saudi Arabia has been reported to be considering the purchase of a 50 percent interest in three of Texaco’s refineries. More than seventy miles from Three Rivers, in Corpus Christi, the Champlin refinery is now half owned by the national oil company of Venezuela. No one knows what the foreigners might do, but there are fears that the Saudis’ long-range plans might include shutting down U.S. refineries to open markets to products refined in Saudi Arabia.

The Three Rivers refinery, like the rest of the Texas oil industry, no longer has control of its own destiny. The refinery is by far the largest employer in Live Oak County, and workers have seen a 25 percent reduction in personnel since 1978. In the boom years, broken pumps were sent out for repair; now pumps are rebuilt in the refinery’s own machine shop. “Something has to be done so refineries can make more profits,” said Art Gamez, a $13-an-hour employee at the plant. “I’m a family man with three children. I depend on this plant.”

- More About:

- Energy

- Business

- TM Classics