For years, the tantalizing prospect of Texas becoming a “purple” battleground state has motivated Democrats—who have had their hopes dashed in election after election. However, the 2018 midterms showed cracks in the GOP’s hold on the state, with Democrats picking up congressional seats in districts that were drawn by Republican mapmakers to be easy holds. Now polling suggests that 2020 could see further gains by Democrats.

While all eyes are on the presidential campaign, and, er, some eyes are on the surprisingly low-profile Senate race between GOP incumbent John Cornyn and Democratic challenger MJ Hegar, the fiercest battles in Texas are over seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Four years ago, the state had just one competitive congressional race; this year, there are a dozen races both parties are acting as if they’ve got a real shot at winning.

Today, we’re continuing our “Get to Know a Swing District” series with a look at Texas’s Twenty-first Congressional District.

The District

History

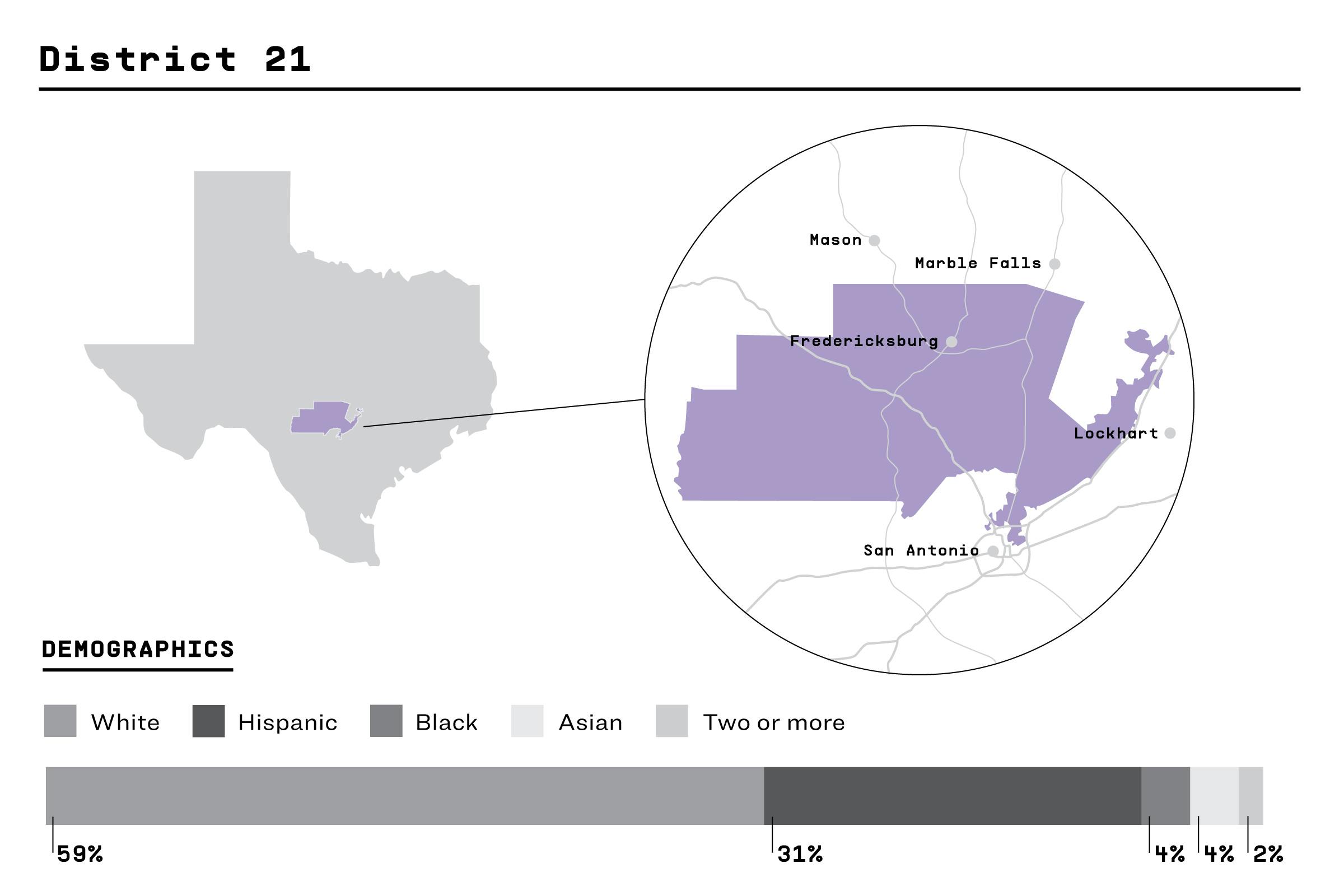

Republicans have held Texas’s Twenty-first Congressional District—which covers parts of Austin, San Antonio, and a big chunk of the Hill Country—since 1979. From 1987 to 2019, Lamar Smith represented it, typically winning by 20-point margins. Sometimes, as in 2008 and 2014, Democrats didn’t even field an opponent.

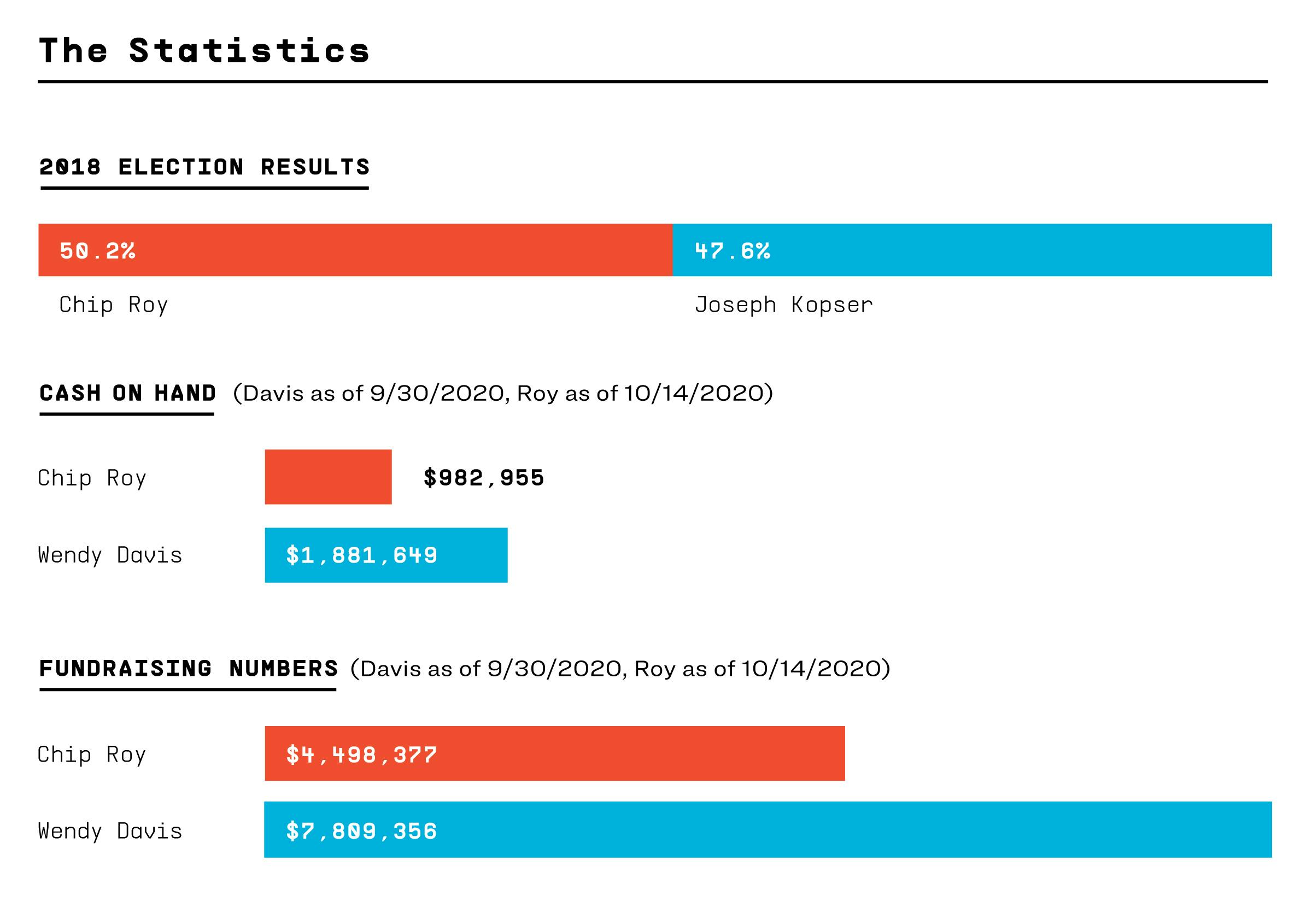

In 2017, Smith announced that he would retire at the end of his term, presaging the “Texodus” from Congress of a half-dozen Republicans who decided not seek reelection in 2018 and 2020. A free-for-all ensued: eighteen candidates received votes to replace Smith in the GOP primary, and four Democrats sought their party’s nomination. In November of that year, Republican Chip Roy—former chief of staff to Ted Cruz and a first assistant attorney general to Ken Paxton—prevailed over Democrat Joseph Kopser, an entrepreneur and Army veteran. But Roy’s narrow margin of victory—only 2.8 points—immediately made TX-21 a district Democrats eyed to flip in 2020.

What It’s Shaped Like

Nothing in nature is shaped like Texas’s Twenty-first District. Maybe, if you’re imaginative, it looks like one of those cartoon whales with a giant head, poised to swallow Brackettville. The district comprises a large, block-shaped western portion connected narrowly to a slender eastern edge. That edge pulls in a small selection of Austin and San Antonio voters and many—but not all—of those who live along the west side of Interstate 35 between the two cities (there’s a narrow carve-out in San Marcos that, not coincidentally, keeps Texas State University students out of the district). The golf course across the street from Schlitterbahn is in the district, but the water park is not.

In San Antonio, the district includes some of the more affluent and conservative North Side neighborhoods, as well as the airport and municipal enclaves including Alamo Heights. In Austin, the district includes wealthy, and liberal-leaning, urban neighborhoods including Travis Heights and the South Congress strip. The district’s rural western block—combined with the more affluent and suburban residents outside of San Antonio and Austin—have kept it a GOP stronghold.

The Candidates

Meet Chip Roy

Many Republican candidates running in unexpectedly competitive districts have tacked to the middle. Not Roy, who has followed in his former boss Cruz’s footsteps by alienating members of his own party, including through actions costly to Texas. In 2019, he held up a $19.1 billion disaster-relief package that would have expedited aid for the state and that had already cleared the U.S. Senate, objecting on procedural grounds. In March 2020, he voted against the coronavirus relief bill—one of just a few dozen representatives to do so—and argued that Americans should return to business as usual and develop “herd immunity” by becoming infected with the virus in such large numbers that it will run out of susceptible hosts—an approach that experts in epidemiology say would result in millions of needless deaths.

While other Texas Republicans talk about repealing the Affordable Care Act but preserving its protections for pre-existing conditions, Roy doesn’t even pay lip service to that portion of the law. He describes the vows of his party-mates to repeal the ACA as “a broken campaign promise,” and calls for a private insurance system he dubs “healthcare freedom.” He argues against restrictions on carbon emissions and for increased usage of renewables only as they become “financially viable.” Roy’s not only for a border wall, but wants “to stem the tide of illegal presence” through increased Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids and arrests inside the U.S.

The incumbent has built his reelection campaign’s fundraising pitch around his opposition to defunding the police. He’s raised more than $4.2 million through the third quarter of 2020 and has just under a million on hand for the campaign’s final stretch.

Meet Wendy Davis

You’ve probably already met her. If you lived in Texas in 2014, you may have cast a ballot in her race for governor. If you’re new to Texas, you might recognize her as the star of the 2013 filibuster of Senate Bill 5, which would have banned a slew of abortion procedures around the state. The pink running shoes she wore on the Senate floor became iconic, she published a memoir, and a biopic of Davis has been in development for several years. (Sandra Bullock, at one point, was attached to play the former state senator).

After losing her campaign for governor by a 20-point margin, Davis took a few years to regroup, moving from Fort Worth to Austin before setting her sights on Congress. She’s not on her party’s leftmost flank, but there’s nonetheless a stark contrast between her platform and Roy’s. Davis proposes a public option allowing individuals to buy into Medicare, but not Medicare for All. She wants the U.S. to re-enter the Paris Climate Accords and end Trump administration rollbacks of EPA regulations, but does not embrace a fracking ban or the Green New Deal. She also wants to raise the federal minimum wage to $15, institute universal background checks for gun purchases, ban the sale of military assault-style weapons, and create a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants currently in the U.S. Her campaign platform conspicuously makes no mention of abortion, though she’s still pro-choice.

Davis’s high profile has helped her raise a staggering amount of money. At the end of the third quarter, she’d brought in just shy of $8 million, of which nearly $1.9 million remained in the bank for the race’s home stretch.

The Upshot

Why It Could Flip

Davis would benefit if Joe Biden performs well across the state, but the district is close enough in its partisan alignments that she’s not reliant on coattails to succeed. Her path to victory runs through the once-Republican suburbs along the I-35 corridor that some Democrats now regard as the “blue spine” of Texas, and turning out voters there who may be put off by a GOP candidate who has eschewed moderation. The Twenty-first also covers one of the fastest-growing parts of the state, which gives Davis new voters to court.

There hasn’t been any non-partisan polling of the district, but Davis’s own surveys have consistently shown a race within the margin of error.

Why It Might Not

Roy triumphed over an attractive, centrist opponent in what was a strong year for Democrats in 2018. This cycle he could benefit from running against an opponent about whom many voters have strong opinions: Davis’s high name ID comes with established negatives. There are parts of TX-21 that Davis lost by 60 points in her gubernatorial run. And those parts (think New Braunfels) have been growing as rapidly as any in the district. If those conservative voters turn out in high numbers, and the overall dynamics statewide aren’t appreciably better for Democrats than they were in 2018, Roy is well-positioned to keep his seat.

The Bottom Line

This race is a toss-up according to the Cook Political Report, while the pollsters at FiveThirtyEight are slightly more bullish on Roy.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Wendy Davis

- Chip Roy

- San Marcos

- San Antonio

- Austin