In the years after unarmed teenager Trayvon Martin was fatally shot by a member of a neighborhood watch group in Florida in 2012, James Nortey, an attorney, felt called to get involved in his community in Austin. He began attending forums about policing, where he noticed that representatives from the Austin Police Department typically deflected when asked critical questions about the department’s use of force, encouraging those who asked them to sign up for the Citizen Police Academy. “That kind of gave them cover to avoid tough questions or give authentic answers,” Nortey said. So in September 2016, he signed up for the fourteen-week, 56-hour, taxpayer-funded course that, according to APD’s Public Information Office, is meant “to build relationships between Austin police officers and the community we serve, and create awareness about how the police department operates.”

Nortey, who is Black, had had mixed experiences with police: he’d gotten along with neighbors who were cops and had interned with the police and sheriff’s departments in Waco, but he’d also been racially profiled before—once, he was stopped while leaving a Baylor University basketball game by police who, according to Nortey, were looking for someone wearing green and gold, the school colors. He found the CPA course in-depth and informative. Most of the classes involved presentations from officers in APD’s various specialized units, moderated by the academy’s lead instructor, Surei Scanlon, who works in APD’s Public Information Office. Nortey took notes as officers explained the inner workings of the department’s SWAT and K-9 units, the ways APD investigates cold homicide cases, and its recruitment of future cops. Curious why police unions often defended bad police behavior, he even successfully lobbied for the leadership of the Austin Police Association to give a presentation to the class.

According to interviews with four students who’ve taken the CPA in the last four years, the program reinforced some participants’ sympathy and support for the police, particularly regarding situations when officers use lethal force. But students, including Nortey, said some of the classes also seemed to downplay community concerns about systemic racism and police brutality and that critical questions were met with defensiveness. In one class, students were shown raw video footage of police killing and violently arresting citizens—including some unarmed Black men and women—and were told the police actions were justified. In another, students role-played as police officers, were given fake guns, and responded to interactive video scenarios, including one in which a Black man becomes violent during a traffic stop.

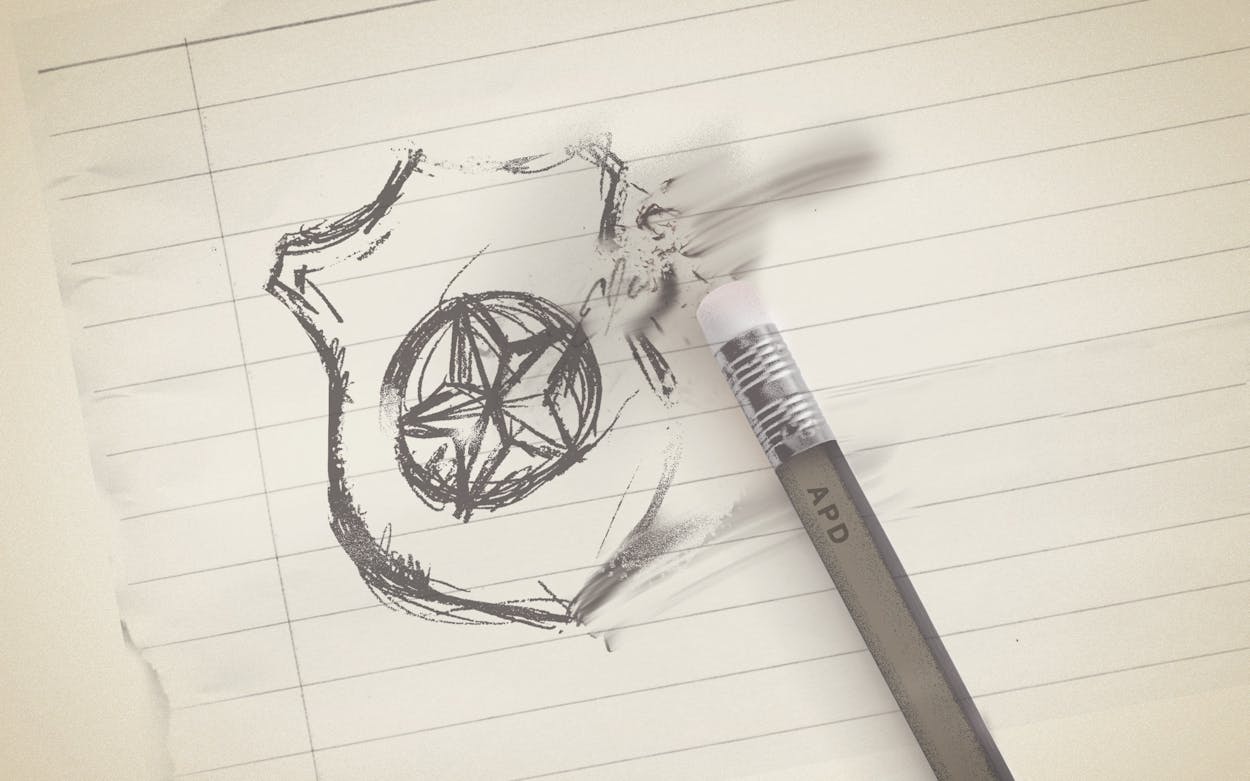

These classes left participants, particularly those of color, disheartened. Some wondered whether the academy serves to build trust between APD and the community, or whether it’s mostly a tool for enlisting citizens to spread unquestioning support for the police. The recruitment of ambassadors for APD doesn’t end with the academy. Many graduates continue as members of the Austin Citizen Police Academy Alumni Association—a nonprofit organization independent of APD—and in that role are asked to raise money for the department and, according to email records reviewed by Texas Monthly, to advocate for law enforcement in front of the city council. Local social justice activists question whether the CPA exists to serve APD’s interests rather than those of the taxpayers who fund it.

APD confirmed in interviews the contents of the course, but rejected multiple requests for an interview about the alumni association and students’ criticisms of the class.

Nortey said there was no indication that the questions and concerns he raised during the course resulted in APD taking any action to address deep-seated problems in policing. “It’s not a two-way conversation at all,” Nortey said. “The CPA gave me a greater empathy for what it’s like to be an officer. But it’s not clear to me that they have much sympathy for the devastation and pain and loss the community feels” when some officers use excessive force or discriminate against suspects because of their race.

The first citizen police academy was launched in Orlando in 1985, and the idea spread throughout the United States, reaching Austin just two years later. Since then, more than 2,700 Austinites have completed APD’s course. The application to enroll is extremely thorough. Potential students must consent to a criminal background check and disclose personal information including any amputations, scars or tattoos on their body, and any “civic or social groups” that they participate in. A long list of factors may disqualify applicants from taking the class, including having been charged with a felony, having been convicted of various misdemeanors, or being a “known associate of a convicted felon,” while other “indications of criminal history” are evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Nortey’s class was mostly white, in a city where just over half the residents are people of color. Shawntea Degrate, a biracial paralegal who took the class in 2018, said her class was slightly more diverse, but still majority white. Questions about the necessity of lethal force were typically raised by people of color in the class, Degrate and others say, while their white classmates often expressed pro-police sentiments, or otherwise were noticeably quiet on controversial subjects such as racism and use of force.

Kathryn Statos, a psychology instructor at Austin Community College who took the class in 2017, said she encourages her students to take it, and even persuaded her mother to do so. “I have a lot of students that are, you know, I don’t like to say this, but [have] a real hatred for the police,” Statos, who is white, said. “This is one way to encourage them to gain education and more understanding so that they don’t have such a jaded thought process toward the police.”

But some people of color who found the course informative at first became jaded by the end. For them, two lessons stood out. One of the final classes was titled “Response to Resistance,” and covered use of force. Three students remembered being shown footage of the fatal police shooting in 2018 of 22-year-old Stephon Clark, an unarmed Black man who was shot multiple times in the back after police mistook his cellphone for a gun. The shooting took place in his grandmother’s backyard in Sacramento, California. Prosecutors ultimately deemed the shooting justified, and the officers who killed Clark did not face criminal charges and retained their jobs.

Rosemary Hook, a Hispanic woman in Degrate’s 2018 class, recalled that the APD representative who presented the class didn’t seem to take Clark’s killing seriously, and some students even laughed during the discussion, with the video paused on an image of Clark lying dead in his grandmother’s backyard. “They were showing us videos that I think they thought demonstrated how use of force was necessary,” she said. “And it really had the exact opposite effect for me.”

Hook became so disillusioned that she ultimately decided not to attend the graduation ceremony or participate in the alumni association, even though she was voted vice president of her class. “As a person of color, there were a couple of times during that fourteen-week class that I was equally horrified at the blasé attitude toward overuse of force, and at my Anglo classmates’ indifference to unarmed Black men being shot,” she said.

In another lesson, members of three graduating classes of the program recall, students were taken to an off-site training facility, where those who agreed to participate were given fake guns and tasked with responding to situations that unfolded before them on an interactive video screen. There were two scenarios. In one, an older white man who appeared to be experiencing homelessness was acting erratically while trying to get inside a building, and at one point he reached for his waistband and pulled out a gun. The other video showed a large Black man getting out of his car during a traffic stop, posturing, and acting aggressively. In both scenarios, the men begin to attack if the “responding officers” don’t shoot their guns, students said.

Texas Monthly filed an open records request seeking copies of the videos, but APD said it could no longer access the video files, writing in an email that the technology system used for the video training exercise “is no longer functional and will not be repaired for future use.” In an interview, Surei Scanlon, the lead instructor of the CPA, confirmed the details of the videos used in the training exercise and the scenarios they depicted.

Scanlon said that students could choose not to participate in the exercise if they didn’t want to, and were not forced to fire their fake weapons during the training. “These were just thought-provoking scenarios,” she said. “It’s all about perspective and recognizing what an officer is going to potentially encounter, and how quickly that officer is going to have to make that decision. It’s been a very powerful experience for people to have a better understanding.”

The training exercise seemed to solidify Statos’s support of police. “It was very eye-opening,” she said. “It’s gratifying to know that there are people that are willing to go out and do such a difficult job.”

But other students say that the video scenarios played into harmful stereotypes. “I think implicit in the message is that homeless people are inherently dangerous, Black people are inherently dangerous,” Nortey said.

Another CPA student, who requested anonymity out of fear of facing retaliation from APD and its supporters for speaking critically about the police department, said that after participating in the video training, her questions about potential alternative responses that didn’t involve lethal force were left unanswered. “Right away, I was like, why is that our only choice? Why do we only have a gun? What about having pepper spray or a Taser?” the student said she asked in class. “They said, ‘We don’t have time for that.’ To me, it was sort of subtly putting in your mind that these are our only choices.”

APD spokesperson Angelique Myers rejected an interview request specifically focused on the way the CPA addresses use of force and, in an emailed statement to Texas Monthly, did not address any of the claims students made about their experiences.

Near the end of the class, students are offered the opportunity to join the CPA’s nonprofit alumni association, whose members sometimes serve as stand-ins in police training exercises and often hold fundraisers for APD. According to public posts on the Austin Citizen Police Academy Alumni Association’s website and emails obtained by Texas Monthly, the alumni association’s leadership has also asked members to help create positive press coverage for the department, and to lobby the city council to increase APD’s funding.

In early June, the APD Twitter account posted a photo of officers smiling in front of a banner that read “Thank you for your Service” as they opened hundreds of thank-you cards the department had recently received. “We can’t express enough how grateful we are to serve you, Austin,” the department wrote in a tweet, alongside photos of the cards. “Our officers have been working around the clock during these unprecedented times and thank everyone who took the time to write and make our day a little brighter.”

The tweet came days after the department had drawn criticism for excessive use of force by some of its officers at several protests in late May following the extrajudicial killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis. At least 41 protesters had been injured by police armed with “less-lethal weapons,” including dangerous beanbag rounds, which broke ribs, fractured skulls and jaws, and ripped through cheeks. Degrate had attended one of the demonstrations, curious to see how APD handled them, and had felt her eyes burn after police sprayed a type of irritant. “I didn’t see those officers try to engage in a positive way,” she said. “They would smirk and just stand there.”

APD’s tweet prompted speculation that the cards had been faked, after Twitter users noted many of the envelopes had identical handwriting. As Texas Monthly reported in July, some of the cards contained bizarre messages, including telling officers “your butt is perfect.” APD released a statement to reporters after the Twitter post stating that the cards came from “several community members,” including “kindergartners and Austin families who wanted to show support for APD officers.”

According to emails obtained by Texas Monthly, the alumni group coordinated the thank-you card drive with APD’s help, putting out a call to its members to write them before dropping them off at APD headquarters. Even the banner was made by the president of the most recent CPA class.

On June 3, Scanlon sent an email to the president of the alumni association, commenting on the pandemic and recent protests. The alumni association president forwarded the message to the alumni members at Scanlon’s request, adding “suggested items” to donate including Gatorade, bags of trail mix, and “hand-written cards with words of encouragement.”

Three days later, and two hours after APD posted the tweet about the cards, Scanlon sent an email to three other officers in APD’s Public Information Office, with the alumni association’s president copied. “The CPA Alumni’s mission is to support law enforcement,” she wrote. “Alumni members are ambassadors of APD and Law Enforcement as a whole.”

Meanwhile, the city’s police oversight commission received hundreds of complaints about APD’s use of force during the protests, and the city council scheduled an emergency meeting in early June. Amid public discussion about reallocating police resources, APD was suddenly at risk of losing millions of dollars.

In Scanlon’s June 3 email, she called George Floyd’s death “senseless.” In the next paragraph, she encouraged the alumni association members to attend the upcoming emergency council meeting. (Members of the CPA alumni association had been urged to advocate for APD before the city council in the past, other email records show.) “Let me be clear, I am not requesting anyone speak, or that anyone speak on behalf of APD,” Scanlon wrote to the “ambassadors” of APD. “I am just providing you information that a meeting is taking place today and that you can observe or participate.”

While Scanlon carefully avoided appearing to directly ask the alumni members to advocate for APD before the council, the message still troubles local criminal justice reform advocates, who believe it further muddies the relationship between APD, the students in taxpayer-funded CPA classes, and alumni of the program. “This email raises serious questions about whether the police department is using city funds to enable people to lobby the city on their behalf,” Chris Harris, a member of Austin’s Public Safety Commission and director of Texas Appleseed’s Criminal Justice Project, a social and economic justice advocacy organization, said after being shown Scanlon’s email. “This also appears to further justify efforts to move the public information office, among other units, out of the police department so that their activities serve the public’s interests, not the interests of the police department.”

When shown the same email from Scanlon, Nortey, who is not part of the alumni association, said he was not surprised. “You’ve already preapproved and screened them so you know what they’re going to say,” Nortey said. “Then people think that this group of alumni are representative of the community, when they’re not.”

Only a few Austinites spoke in support of APD at the city council meeting—none immediately identifiable as CPAAA members. After hours of testimony from Austinites, the council unanimously voted to ban APD from using “less lethal” weapons, such as beanbag rounds and tear gas, at protests. Later, in August, the council unanimously approved a budget that included $150 million in cuts to APD’s budget, making Austin one of the few cities in the country to reallocate public funds from its police department in the wake of protests this summer. According to the Texas Tribune, funds that APD had earmarked for planned future cadet classes will be redistributed to violence prevention and food and abortion access programs, while some of APD’s publicly funded civilian functions, like forensic sciences, will be moved under other wings of the city’s government.

Meanwhile, this semester’s CPA class is delayed because of the coronavirus. It remains unclear whether APD will make changes to the course to address concerns about the department’s use of force. “To be more than just a marketing scheme, it needs to do more,” Nortey said. “It’s not clear to me that my attendance, or the questions I raised, that any of that effort was used in moving the ball along and leading to reform.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- George Floyd