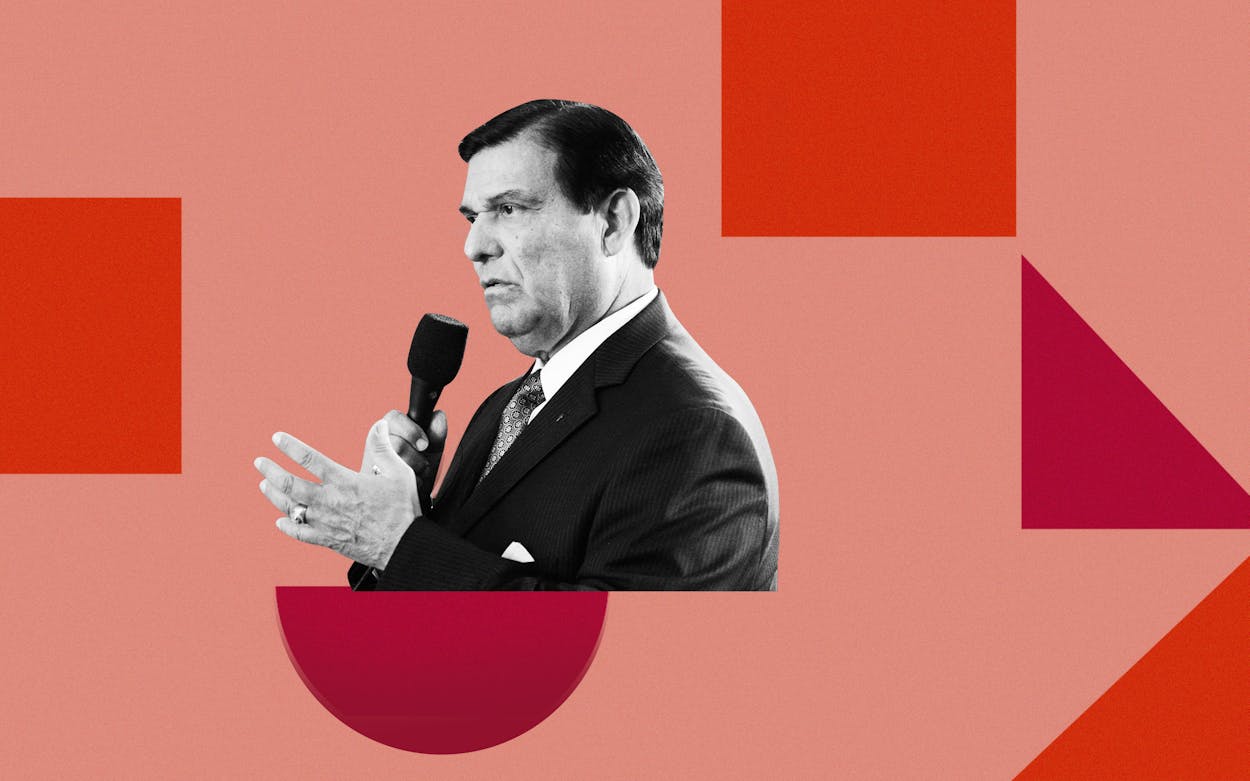

Generating attention for the months-delayed primary runoffs has not been easy in state Senate District 27, where the COVID-19 pandemic is ravaging border communities from Kingsville to Brownsville. That changed, however, at the height of early voting, when a direct-mail piece opposing 29-year incumbent Senator Eddie Lucio Jr., who faces a challenge from attorney Sara Stapleton-Barrera, hit mailboxes.

The mailer, sent in late June and financed by civil-liberties nonprofit the Texas Freedom Network (TFN) and Planned Parenthood Texas Votes (PPTV), leveled all the criticisms Lucio has faced for years. In his three-decade legislative career, the literature noted, the state senator has joined Republicans to support measures including school vouchers, bathroom restrictions for transgender Texans, and abortion rollbacks. It was the mailer’s banner, however, that incited a wave of impassioned responses from Lucio’s allies, and then a counterreaction from his foes: in bold red letters, the incumbent was identified as “Sucio Lucio,” a nickname derived from the Spanish term for dirty.

Within days of the handbill’s arrival in mailboxes, state Representative Eddie Lucio III, the senator’s son, attacked the political action committees behind it for “disparaging our family name with derogatory and racial slurs” over their “traditional Catholic values.” Lucio III, who disagrees with his father on the issues the mailer highlighted, accused outside agitators of initiating a smear campaign against Lucio Jr., noting the “deeper connotations” of portraying Texans of Mexican descent as grimy.

Immediately, several of Lucio III’s Democratic colleagues and allies took to social media to support his comments. Within an hour, Stapleton-Barrera’s allies heard that the Mexican American Legislative Caucus (MALC), the often powerful, bipartisan forty-member body in the Texas House, was planning to weigh in, potentially targeting her campaign, TFN, and PPTV. It appeared to be a pointed display of institutional force in the making. When the MALC statement came, however, it was just a few short lines, vaguely decrying “discriminatory undertones that have crept in campaigns.” The caucus, notably, had abstained from commenting on other news this cycle where racist rhetoric grabbed headlines.

The entire spectacle seemed disproportionate to the race, in which Lucio Jr. has been heavily favored. In a three-candidate race in March, the senator finished just short of the 50 percent mark to win outright and avoid a runoff. While even uncompetitive races in Texas can receive a “knives out” treatment, “Sucio Lucio” is hardly a new nickname. Stapleton-Barrera, 36, who clarified that the mailer “didn’t come from my campaign,” said she remembers the term being around since she was a child in Brownsville. Lucio Jr., 74, told me that he had heard it before. Why, then, was it now inciting such a hasty uproar?

The reaction is a function, in part, of the fact the senator is not accustomed to protracted primary fights. The four-month runoff, delayed by the coronavirus, has allowed anti-Lucio energy to draw out longer than it ever has before. But the debacle also exposes growing generational confrontations in the Rio Grande Valley, a reliable Democratic stronghold where many community groups and institutions are tied to the Catholic church and remain socially conservative. Other elected officials in the region, while Catholic as well, are farther left on social issues than Lucio Jr., including his son. But Valley politics can often be at odds with those of other Democratic strongholds around the nation. Young progressives in South Texas are now vying to change that.

Lucio Jr. has made a name for himself aisle-crossing in a chamber where Republicans have outnumbered Democrats since 1996. He’s proud of his voting history and says there is nothing “dirty” about it, but younger Democrats in the region consider his collaboration with the other party inexcusable. A more progressive District 27 senator, such as Stapleton-Barrera, might be elected more easily in the near future. Whether progressive challengers can threaten incumbents in the short term, however, depends on their ability to spotlight records they see as “dirty” long enough to convince newer voters the stances are an electoral liability. Stapleton-Barrera and her supporters have attempted this with dogged regularity on social media, which Lucio Jr. mentions as a key source of agitation against him that he has not been able to match because of a lower online profile.

The social media machine of Stapleton-Barrera’s supporters was ready when politicians rallied in the Lucios’ defense. “Initially when we saw it, it was hilarious,” said Brownsville organizer Joe Uvalles. “We thought, ‘We can handle this—we can use our platforms.’ The community was being gaslit.”

Stapleton-Barrera supporters pushed back on Lucio III’s characterization of the mailer and of opposition to his father as outside meddling. Ofelia Alonso, TFN’s field coordinator in the Valley, immediately began organizing a response to the “disrespectful dismissal.” Shared widely on organizers’ social media accounts, their statement said MALC had “blatantly ignored” the senator’s record “that has harmed our Valley community for over 30 years.” Within days, their response had nearly one hundred signatures from local organizers and residents, and they followed with an online town hall about the controversy that reached an estimated viewership of two thousand.

Lucio III, who did not respond to requests for interview, notably followed up with a string of tweets explaining his support of progressive and LGBT causes in the Valley, but he stood by his claim that the mailer had employed a “derogatory context.”

Stapleton-Barrera’s support of abortion and LGBT rights—or as she pointedly puts it, “my plan not to discriminate against anyone”—has been a key part of her appeal to younger voters. It has also served as a singular target of attack for Lucio Jr. and his allies, including powerhouse conservative groups such as Texas Right to Life and the Koch-backed Texans for Lawsuit Reform and Libre Initiative Action. That Lucio III issued a partial walk-back seemed, to some Valley activists, a significant measure of their power to control the narrative when it mattered.

“I don’t think he expected the backlash from his initial statement,” TFN’s Alonso said. “He realized that he had gotten himself in a situation where he had been called out for a very similar thing his father has, which is not listening to his LGBT constituents.”

Cindy Gonzales, a three-term Kenedy County commissioner who endorsed Lucio Jr., cautioned that online buzz is no substitute for a ground game, but she acknowledged its power. “Ms. Stapleton-Barrera seems gung ho and, on Facebook, many young people gravitate to that,” she said, “but he has the experience.”

PPTV and several progressive organizers in Brownsville also repudiated the charge that the group had parachuted into South Texas. Longtime adversaries of Lucio Jr.’s, the group has been involved in advocacy and training in the Valley for seven years and in the SD-27 race since January, according to Dyana Limon-Mercado, PPTV’s executive director. “They wouldn’t have used that term, ‘Sucio Lucio,’ if it were not for constituents calling him that,” Uvalles said in the group’s defense.

Progressive challengers have started to run closer in the Rio Grande Valley in recent years, which Stapleton-Barrera cites as a hopeful trend. In March, U.S. representative Henry Cuellar, the conservative Laredo Democrat and 15-year incumbent, narrowly fended off his primary challenger, the 26-year-old, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez–endorsed attorney Jessica Cisneros, by 3.6 percentage points. “If [Cuellar] was so loved by his community, then he wouldn’t have just barely won that race,” said Valley activist Denisce Palacios, who estimates that fifteen volunteers she knew from the Cisneros campaign joined Stapleton-Barrera’s after Super Tuesday.

“People thought I was crazy, but over the past year, it’s taken a drastic turn,” Stapleton-Barrera, who garnered 35 percent of the vote in March, told me of her support. “People are recognizing there’s a shift. Once I started feeling that in the air, I got a real sense I may be able to do this.”

While Lucio Jr. told me that he accepts that “time brings change,” he cannot imagine the next legislative session—which he says will be his last—without him on the redistricting committee. He’s warned since last year that a post-census apportionment session is no time for a young freshman legislator. He also is not convinced his politics are being left behind quite yet.

“I represent the vast majority of people here,” he told me on the last day of early voting. “You’d be surprised how many young people are pro-life or who practice their faith. I respect people who need to live another lifestyle. I pray for them, but religion should never change—that’s been around for centuries now. Young people are still lost.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Rio Grande Valley