Can museum audiences, or museums themselves, be trusted with potentially traumatic, inflammatory, and divisive imagery? When is it a museum’s role to provide context about provocative art—and why is it seemingly such a daunting task? Who gets to make and display paintings about the Ku Klux Klan? These questions and more have become flash points of debate in the American art world in recent weeks, as controversy has swirled around the four-year delay of a much-awaited retrospective exhibition of work by the late American artist Philip Guston. The four participating museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), announced last month that they are postponing the show until 2024, “a time at which we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.”

Guston, who died at age 66 in 1980, was a white, Jewish artist who often used images of hooded Ku Klux Klan members in his later paintings. Though his work is increasingly relevant to public discussions of systemic racism, he has not been the subject of a major museum retrospective for more than fifteen years.

Cherise Smith, an art history professor and chair of the African and African Diaspora Studies Department at the University of Texas at Austin, has a guess about the institutional motivations behind the delay. “Given the fact that we’re in the middle of the Black Lives Matter movement and we are besieged as a country by a surge of white supremacy … I am sure that the museums just felt like it was a topic that was too hot to handle,” Smith says.

If the museums involved in the show—the MFAH; the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.; the Tate Modern in London; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—were hoping to avoid controversy by pushing back the Guston show, the move has backfired. Their joint statement of September 21, which emphasized the need to “step back, and bring in additional perspectives and voices to shape how we present Guston’s work to our public,” has been roundly lambasted in the press and by a diverse array of art-world figures. A cocurator of the exhibition called the delay “extremely patronizing” to audiences, and Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, told the New York Times, “The danger is not in looking at Philip Guston’s work, but in looking away.”

Gary Tinterow, director of the MFAH, says he believes it was the right call to delay the show. “The commentary that I’ve seen tends to corroborate our feeling that emotion is so heightened now that it is difficult to have a reasonable exchange of views in the current climate,” Tinterow says. “We expected that the exhibition, to be properly understood, would require a reasonable exchange of views. The vehement response, to me, corroborates that rational discourse is more difficult in this moment.” He adds, however, that he and his collaborators are now tentatively considering opening the show before 2024: “We are looking to see … whether an earlier presentation is possible, and it looks like it may be.”

That move comes in the wake of widespread criticism. On September 30, Brooklyn Rail published an open letter initially signed by nearly one hundred prominent artists—from big international names such as Isaac Julien, Julie Mehretu, and Matthew Barney to major Texas artists including Mel Chin and Vincent Valdez—and eventually cosigned by thousands of supporters. The letter excoriated the museums for their “longstanding failure to have educated, integrated, and prepared themselves to meet the challenge of the renewed pressure for racial justice.”

San Antonio–born Valdez, who has depicted historic lynchings of Hispanic Americans and an imagined meeting of the modern-day KKK in his paintings, says he looks to Guston as an “extremely pivotal teacher” who “found it absolutely essential to use his work to challenge his audience to think critically.”

“For me personally, the decision to postpone is quite alarming,” Valdez says. “I can’t help but feel that it echoes a much larger symptom about a real inability of our nation’s leading institutions, at all levels, to confront our most urgent and pressing issues.”

Guston, like Valdez, began his art career as a muralist, with wall paintings promoting racial justice and anti-fascism in the 1930s. In the postwar period, Guston shifted gears and became a leading abstract expressionist, but during and after the Vietnam War, he returned to figurative and politically committed painting with a series of disturbing, cartoonish canvases featuring roly-poly, almost comical Klansmen figures going about ordinary American lives—driving in cars, lying in bed, looking out a window at a cityscape, and even, in one instance, painting a self-portrait.

Guston’s Klansmen paintings first provocatively depict, then satirically critique, the role of white supremacy as a force in everyday life. “The iconography is very fraught, and what’s useful about what Guston did was to show the ridiculousness of it,” explains Smith.

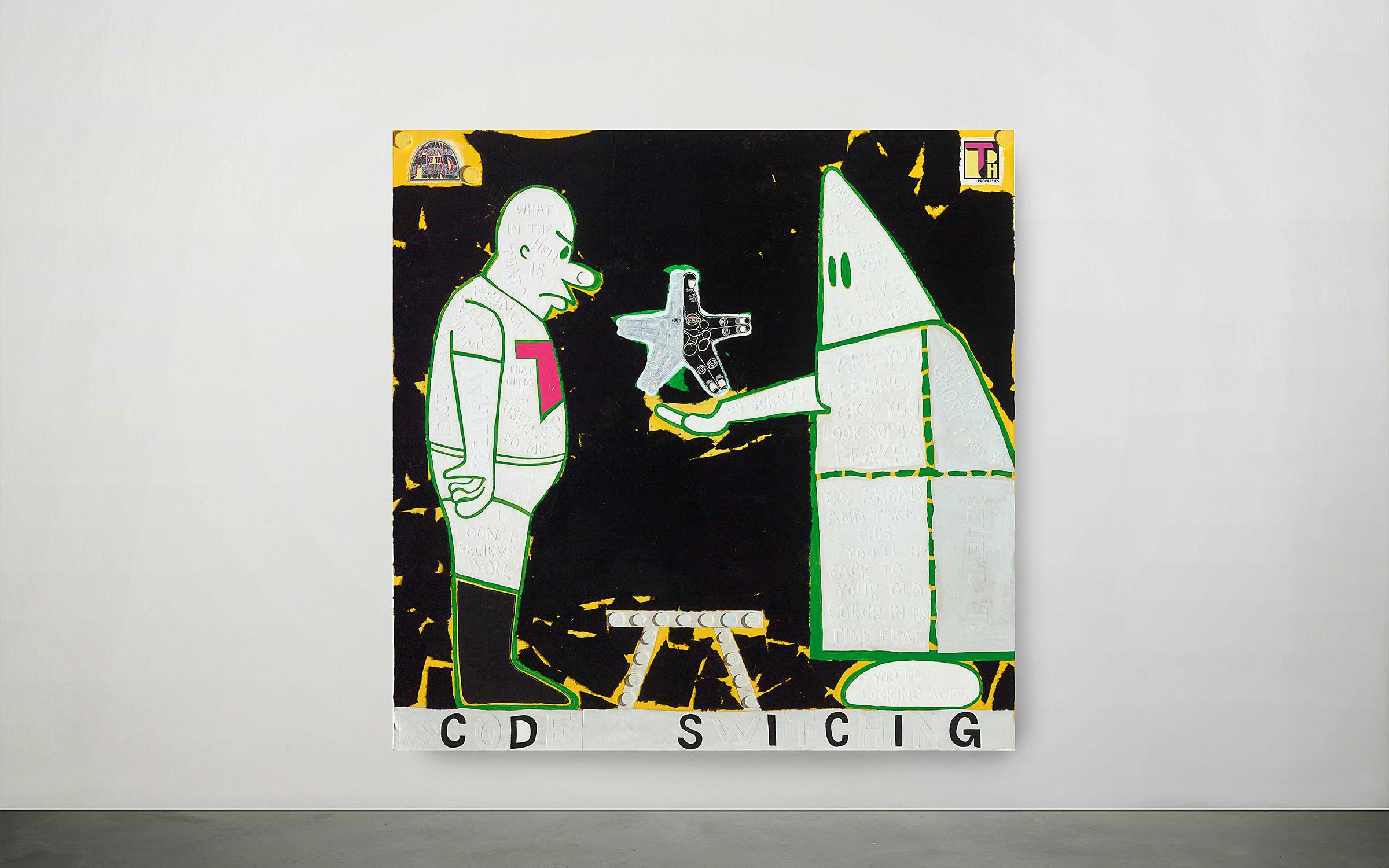

Trenton Doyle Hancock, a Houston-based painter and sculptor, is another prominent Texas artist who has grappled directly with Guston’s legacy in his work. Hancock recently had a solo show at the James Cohan gallery in New York City that featured several paintings in which his on-canvas alter ego, a Black superhero named Torpedo Boy, faces off against or otherwise interacts with cartoonish Klansmen in the style of Guston.

Guston’s work spoke to Hancock early in his career. “I learned about Philip Guston when I was an undergraduate,” Hancock says. “I had been making work based on the Klan image and some attempts to sort of reclaim the power back from the organization for myself. And then I learned about Philip Guston, that he had done that exact same thing for years … I really fell in love with the work at that time.”

Hancock wrote about his perspective on Guston in an essay for the show’s catalog, which was published and made available despite the delay of the exhibition. Like Valdez and Smith, he is suspicious of the museums’ claim that an extensive delay is necessary to provide context. “If the museums are saying that it was an issue of not being able to properly give the voices of context and diversity that are needed … I think they could approach that and we could start to solve those problems,” he says. “I don’t necessarily think that we need to wait four years.”

Smith echoes this suggestion, praising the concept of museum-organized contextual programming, but suggesting that a website or photographs of other artworks in the museum’s gallery space might be appropriate and achievable on a shorter timeline. “I would say that the museum seemed to not trust that it can do the necessary work,” Smith says.

Valdez knows something about curatorial caution around provocative, KKK-related artwork. His Klan-themed painting series The City was displayed at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin in 2018 after a yearlong delay that the museum’s director, Simone Wicha, attributed to the election of Donald Trump and a desire not to have the work be seen as a protest of the president. The Blanton launched a major contextualization program around Valdez’s work, including building a website, hiring six gallery hosts, adding a sign outside the gallery reading “May elicit strong emotions,” and hosting a series of public panels and conversations about the work—including one led by Smith.

“I think that it didn’t do any kind of disservice to the work itself, because these kinds of conversations within the institutions are more necessary, more important, than ever,” Valdez says of the Blanton’s efforts. “But I also think in many ways [museums] are still lacking, and this is the problem.”

Valdez sees today’s museums as hamstrung to take on exhibitions of work like his and Guston’s because of a lack of diversity on their staffs. In 2018, people of color held only 20 percent of all leadership roles at U.S. art museums; of those, 4 percent were Black.

“I feel very strongly the notion that if institutions were really connected and aware of what was most urgently pressing in their community outside of the art world … then they’d have a better understanding of how to articulate and present exhibitions and topics such as Guston’s work,” Valdez says.

Tinterow clarifies that, for the MFAH’s part at least, the delay was not about a four-year process of developing resources to put the art in context. “It’s not that we need some specified amount of time,” he says. “From my perspective, it was more about an external environment and heightened emotion that we’re seeing in all intellectual discourse.”

Museums have been criticized for presenting racially provocative works by white artists before. In 2017, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City displayed “Open Casket,” Dana Schutz’s gruesome painting of the beaten and drowned corpse of Black civil rights martyr Emmett Till. Protests ensued, with some Black artists and activists demanding that the museum take down the painting. (The Whitney did not curtail the exhibit but did host a discussion in response to the debate.) With this and other recent controversies in mind, it seems likely that the museums involved in the Guston show were fearful of a backlash. Michael Auping, the former chief curator at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth who organized a Guston show there in 2003, told Art News that he thinks that’s the case.

“I’m sensing uncertainty and paralysis in a lot of cultural institutions, given all the changes that are happening,” Auping said. “… They’re afraid to be called out on something.” Museums may be especially reluctant to take risks now, as they face severe financial pressures during the pandemic. Staring down large budget shortfalls, many art museums have resorted to furloughs and layoffs, and at least one, the Brooklyn Museum, has begun selling off paintings in order to stay afloat. The MFAH, whose $1.3 billion endowment makes it one of the nation’s wealthiest art museums, is in a relatively strong position.

Was Guston, as a white man, entitled to depict the KKK? Hancock believes the answer hinges on what Guston was trying to do in his work—demanding, against prevailing societal pressures of his era, that his audience reimagine white supremacy as a visible, intricate part of American daily life. “Getting the image out in front of people is an important first step, because if people can’t see it, you’re not going to talk about it,” Hancock says. “As far as it being offered by a Black artist or a white artist or whoever, I think you have to look at context and intent. What is this artist trying to approach with the symbol? Because no symbol is good or bad. It’s how you use it.”

For Smith, Guston’s art certainly merits contextualization for today’s public, but that sort of work is what museums should exist to do. “It is controversial work, but the artist himself had a commitment against white supremacy and the Klan’s nationalism, and the museum should trust that they would be able to … unpack this work intelligently,” Smith says. “It’s exactly the right place to debate and talk down this white nationalist thinking that’s so prevalent right now.”

To Valdez, above all, Guston is a giant of American art, and what is problematic in this moment is not his work but the idea of major art institutions requiring a lengthy delay to figure out how to more fully face up to his vision.

“I can’t help but think about this decision and consider reversing the logic behind it,” Valdez says. “What I mean by this is, take for example artists like Guston, James Baldwin, Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, Maya Angelou, and the countless other thinkers who have found it necessary in their moments to challenge American society. Imagine that they postponed those radical creative moments until they found it a more suitable time to comprehend and confront racial injustice. They are who they are, as pillars in the canon of American history, because they realized that that time was not later, it was now. It is now.”