I won’t try to convince you that $2 a day was a lot of money to earn in 1972, though it was if you happened to be eight years old and had no money of your own because this was your first job. Saturday and Sunday, noon to sundown, we were hired to place little kids on Shetland ponies and guide them in a big loop around an empty field, which sat across the street from the Pancake House. One loop cost a quarter.

The four ponies—Red, JoJo, Happy, and Whitey—belonged to Mr. De la Rosa, who kept them in a corral just down the alley from his trailer home. My father had gotten me the job. A tick inspector for the USDA, my father used a quarter horse to patrol the banks of the Rio Grande, looking for any livestock that might have crossed over from Mexico. He rode his horse five days a week, in all kinds of weather and even after back surgery laid him out and it was a year before he could ride again. His work also involved issuing permits for livestock in the county, which is how he met Mr. De la Rosa, who was in his seventies and retired, except for his pony business.

The best part of my job was when there weren’t any customers and Mr. De la Rosa would leave to run an errand. It felt good to know he trusted us to watch his business for a few minutes, that he had that much confidence in us. Then again, he was leaving four ponies with four boys, none of us over the age of ten, and it was only a matter of time before we started acting our age. After trying to see who could get Red, the fastest of the bunch, to circle the field in less than thirty seconds, we’d move on to trick riding. Balancing on his saddle, I managed to get around the loop standing on Happy, the brown-and-white pinto who clomped along with his eyes half shut. Later we took turns leapfrogging onto the saddle as we’d seen cowboys do on TV. But we were also smart enough to keep an eye out for the old man’s green truck.

One night, as my father drove me home, I mentioned that I’d made it around the loop faster than all the other boys, thinking he might be impressed.

“That’s not what the man is paying you for,” he said, “to be playing games with his animals.” He kept his eyes on the road.

“It wasn’t just me,” I said.

“You’re the only one who’s in this car.”

I felt stupid, not for what I had done but for telling him, for thinking he might understand we were just having fun. I hadn’t even mentioned the trick riding. It made me not want to tell him the good news, that Mr. De la Rosa had asked us to ride the ponies in the Charro Days parade. Then I remembered that my father, because of his work, was already aware that the ponies would be in the parade, along with all the other horses he’d signed permits for.

Everyone I knew had been in, or wanted to be in, the parade. Charro Days was the biggest, most special thing that happened in Brownsville, an annual celebration, since 1938, of our cultural ties with our sister city of Matamoros. Like a second Christmas only two months after the first one, we couldn’t wait for it to come around. Men and women, boys and girls, young and old, we all attended in the thousands, many dressed up as the Mexican cowboys that the four-day festival was named after. Regardless of where you were from or how long you’d been here or how well you spoke Spanish or what your last name happened to be, it was the one time of year that everyone in Brownsville was Mexican. On the first day, city officials from Brownsville and Matamoros stood on their respective ends of the international bridge and, at the appropriate time, belted out a grito, the legendary call of the cowboy. The bridge then stayed open for everyone to pass back and forth and the party to continue on both sides of the river. Classes were canceled Thursday and Friday, kids performed traditional Mexican dances dressed as campesinos and señoritas, and the carnival came to town, which for most of us was about as close as we were going to get to a real amusement park.

I knew people who had been on floats in the parade but no one who had ridden a horse down the middle of the street. After the dancers, the marching bands, the Shriners honking their horns, and the politicians waving from the backs of convertibles, it was the horsemen, los charros, who closed the parade. These charros were like the ones we’d seen on TV and at the Grande Theatre, over on Washington, their images blazing across the screen and into our imaginations. These were the charros whom mothers dressed their children like every year, making sure to draw proper mustaches on the boys. These were the charros whom fathers lifted up their girls and boys to see as they passed in the parade, saying, “Someday, that’ll be you.”

On the day we were to ride the ponies, we showed up two hours before the start of the parade and, together with the other riders and their horses, waited in a lot next to the stadium. Through the chain-link fence, I could see two pretty girls sitting on a float, also waiting. They posed for a last-minute photo, one adjusting her rebozo, the other fanning out the vibrant flowers embroidered across her china poblana skirt.

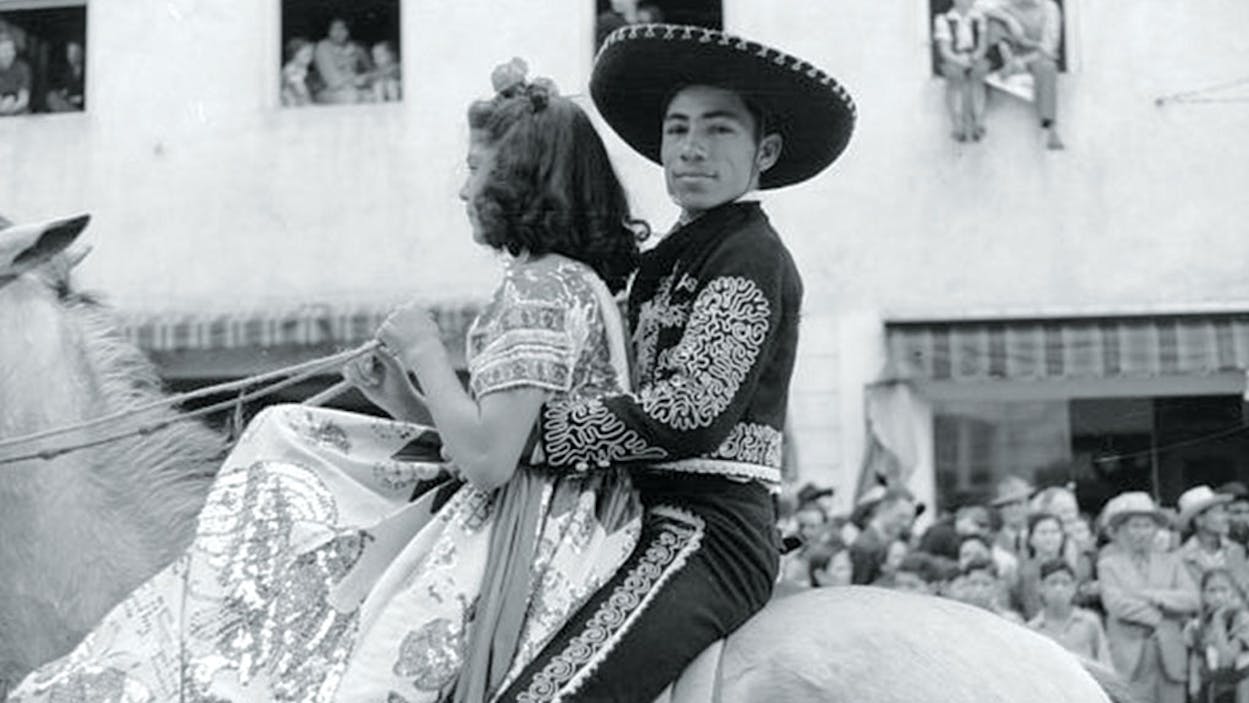

Mr. De la Rosa had bought us wool poncho vests, sombreros, and giant red bow ties that clipped onto our white shirts. He would be walking alongside us wearing the same outfit, but his white hair and browline glasses made him look more dignified, even debonair, as if he were only out for a stroll with his muchachos. The other horsemen, twenty or so of them, were dressed like real charros, with immaculate sombreros, silver spurs strapped to their botines, and embroidered pants and jackets, some adorned across the back with Mexico’s iconic eagle and snake, others with fighting cocks. A few were dressed more modestly, with chaps and sheathed rifles that made them look like rancheros who had just pulled up to water their horses.

Most of these men knew my father, who was also there, in his work clothes, walking around and checking the final animal permits. That morning, over breakfast, he had told me he needed to take me to the farm where he kept his horse. When I asked why, he said that some day I would be riding his horse in the parade. “You should start practicing now,” he said. He’d looked at me, and all I could do was nod. Riding a pony was one thing. To ride a real horse in the parade was altogether different, something I hadn’t considered or thought I might be ready for.

It was time to line up. One of the charros decided that the four boys riding the ponies and Mr. De la Rosa should be the first to exit the gate, followed by the three horsemen holding up the Mexican, Texas, and American flags, then the rest of the charros. Today I would be leading the men; maybe next year or the year after, when I turned ten, I would be holding a flag.

But as I turned toward the gate, the wail of a police siren spooked Red, and I was thrown backward. I had been holding the reins loosely, and now they slid down, past the edge of the saddle and beyond my reach. My right boot tangled with the stirrup before I landed on my back in the dirt. I looked up in time to see Red galloping away.

At the far end of the lot, my father raised his hands chest-high and calmed the pony, until it trotted and finally came up to him. The charros and I watched as he clutched the reins and walked toward us, his gait favoring his left side. He stopped in front of me.

“Are you going to stand up?” he said. He wasn’t reaching down; he was only asking.

Nothing felt broken. The sombrero had probably softened my fall. What I felt was not pain. It was the shock of being thrown. It was the shame of lying in the dirt in my poncho vest and the red bow tie that had managed to stay on as the men, on their horses, loomed over me. It was not knowing if they wanted to laugh at me and weren’t, out of respect for my father. A sob caught in my throat, and I felt myself clenching my teeth, as if I had a bit in my mouth.

“¿Entonces qué?” he said.

My father held out the reins and waited for me to dust myself off. And then I rode out into the parade, the men not far behind.