It is worth remembering this moment. The date is January 7, 2010. The Texas Longhorns are playing the Alabama Crimson Tide for the BCS National Championship at the Rose Bowl, in Pasadena, California. Exactly 3 minutes and 31 seconds have elapsed in the first quarter. Texas defensive back Blake Gideon has intercepted an Alabama pass, and his undefeated team, which is ranked number two in the country, has easily moved the ball to the Alabama 11-yard line. Longhorns star Colt McCoy, the winningest college quarterback in history, is under center. Though this is only Texas’s fifth play from scrimmage, many of his teammates will later recall feeling, in that moment, that they are simply better than their number-one-ranked opponent. They already believe that whatever Alabama does, it cannot stop McCoy.

There is a sense too that something even larger than the national title is at stake. A victory for head coach Mack Brown—his second championship in four years, on top of his already-stunning record at UT of 128 wins and 26 losses—would guarantee his canonization. After a four-decade wait, the Longhorns football program would finally be restored to its Darrell Royal–era glory. Brown would retire a conquering hero, while his designated head-coach-in-waiting, the brilliant Will Muschamp, would seamlessly take his place.

McCoy takes the snap. He keeps the ball, moving to his left and turning upfield. At the line of scrimmage he is tackled by Crimson Tide defensive end Marcell Dareus. As McCoy rises from the pile, there is no immediate evidence that anything is wrong. But in fact the world has changed—deeply and catastrophically.

That’s because Dareus has hit a nerve in McCoy’s right shoulder, which has caused his throwing arm to go limp. McCoy leaves the game, never to return. For Texas players and fans, what happens next is pure heartbreak. Backup quarterback Garrett Gilbert, a true freshman who has thrown only 26 passes in his college career, will throw four interceptions. In spite of those errors, the Longhorns manage to draw within three points of the Crimson Tide with 6 minutes and 15 seconds left to play. But Gilbert fumbles, then throws the game away. Final score: Alabama 37, Texas 21.

Thus do dreams die. Mack Brown’s moon shot burned itself out in the eucalyptus-scented air of Southern California, and the team lugged itself back to Austin, shattered by its strange defeat. But the nightmare wasn’t over—not by a long shot. That school year, 2009–2010, was the culmination of one of the greatest runs in the history of college sports. In 2002 Sports Illustrated had named the University of Texas the “Best Sports College” in the country. Three years later, the Longhorn men won eight Big 12 titles in five sports and two national championships, in football and baseball. The women did almost as well, winning track and field national championships at the outdoor level in 2005 and indoors in 2006. The softball team went to the College World Series in 2005 and 2006 with its incomparable ace, Cat Osterman, while the women’s tennis team finished second at the 2005 NCAA tournament. In 2009–2010 the men’s basketball team started 17-0 and was ranked number one. That spring the baseball team was the second national seed in the NCAAs. Men’s swimming won the national championship that same year. The University of Texas, it seemed, was unstoppable.

And then in a sudden, epic collapse, it all went to hell. In the fall of 2010, Brown’s bizarrely inept Longhorns football team went 5-7. At the end of that season Muschamp abandoned UT to become the head coach at Florida. Over the four years that followed the loss to Alabama, the Longhorns football team’s record in the Big 12 was 18-17. In other words: full-blown mediocrity. The other big men’s sports, the so-called revenue sports, went into weirdly simultaneous swoons. Men’s basketball had two NCAA tournament victories in four years. In 2012 the baseball team failed to make the NCAA tournament. In 2013 its record was so bad it did not even make the Big 12 tournament.

The list of woes was not limited to win-loss records. Augie Garrido, Texas’s legendary baseball coach, was convicted of drunk driving in 2009. Its equally legendary women’s track coach, Bev Kearney, was forced to resign in 2013 for having an affair with a student-athlete. That case led to revelations that Major Applewhite, a former UT quarterback and current offensive coordinator, had had an affair with a student trainer at a bowl game a few years earlier. Later in 2013, basketball coach Rick Barnes watched helplessly as his four highest scorers defected, three to other colleges and one to the NBA draft, where he failed to be selected.

The football team’s lowest point came in a single week in September 2013, when it was humiliated first by BYU 40–21 and then by Ole Miss 44–23. As though to underscore the dysfunctional mess that UT football had become, five days later the Associated Press ran a story saying that UT System regent Wallace Hall and former regent Tom Hicks had, without the knowledge or authorization of UT officials, contacted the agent for Nick Saban, the head coach for Alabama, to ask if Saban was interested in taking Brown’s job.

All of this was happening at the same time that in-state rivals Baylor and Texas A&M were lighting up the college football world with Robert Griffin III and Johnny Manziel, local boys who had attended high school within two hours of Austin and went on to win back-to-back Heisman Trophies in 2011 and 2012.

The final straw came last December, after UT’s lopsided 30–10 loss to Baylor in the final regular-season game. The Longhorn community dissolved into a frenzy of anger, blame, and recrimination, and Brown was called everything from a “has-been” to a “clown.” “The game has blown by Mack Brown like he is in reverse,” read a typical blog post. “Mack is a failure,” read another. The attacks raged for a full week and culminated in Brown’s departure on December 14. It was a cruel end for one of Texas’s greatest coaches. “I think Mack’s departure was handled poorly,” says Steve Hicks, the vice chairman for the UT System Board of Regents. “It should have been a celebration of his accomplishments and not something that embarrassed him the way it did.”

Two months earlier, the empire had suffered another blow: legendary UT athletics director DeLoss Dodds announced that he was resigning. Dodds, who had held the job since 1981, had been the architect of Texas’s athletic dominance. He had engineered the enormous money machine that ran it all and used that wealth to lure the best athletes, build the best facilities, and hire the best coaches, including Brown. Thus did the University of Texas’s most successful sports era end in more than a little pain and turmoil. It wasn’t supposed to be this way. With all this bitterness and controversy, and with Dodds and Brown gone, what would happen next?

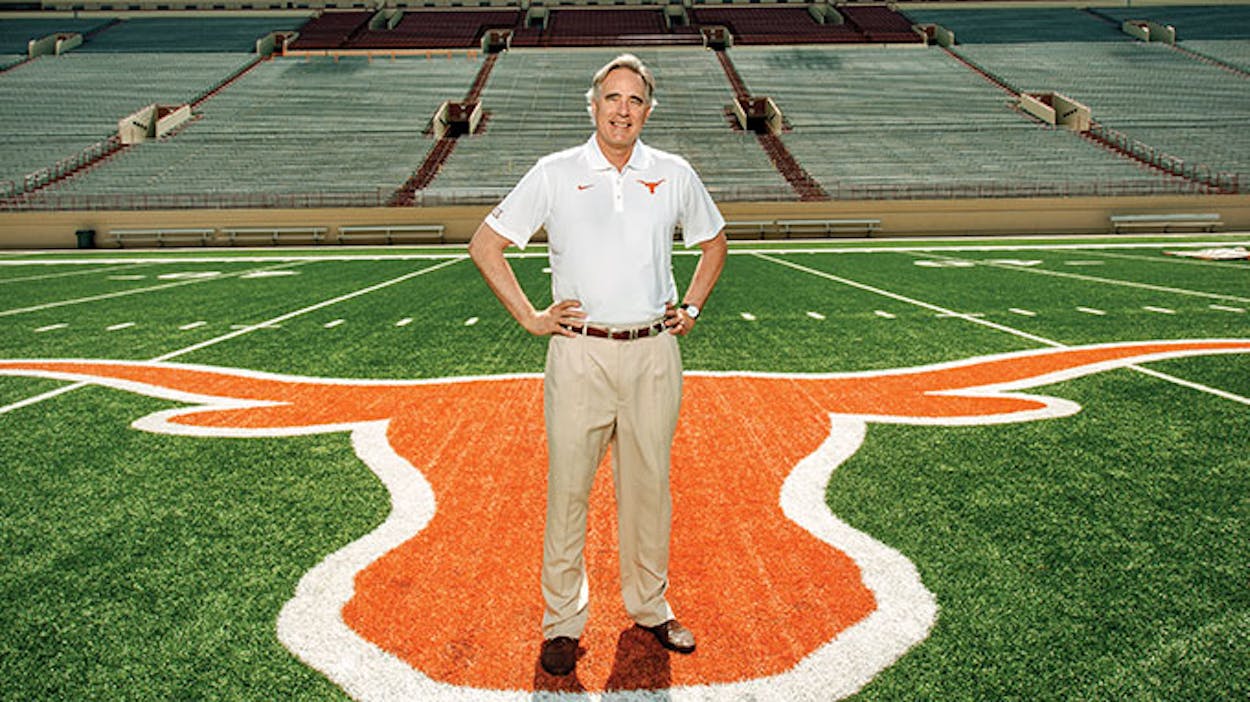

On a clear, sunny spring day in Central Texas, four anda half months after Brown’s resignation, I am cruising on Interstate 35 in Steve Patterson’s black Cadillac Escalade. The 56-year-old Patterson, who was hired away from Arizona State in November 2013 to become UT’s athletics director, is a rangy six feet four inches tall, with graying hair swept back off his forehead. He has a handsome, open face and an easygoing manner that makes you like him right away. He is wearing one of the dark, conservative, chalk-stripe suits he favors, with a tie that looks like it has a swirl of retro paisley in it.

Patterson had been on the job a little more than a month when Brown either resigned or was forced out, depending on whom you talk to. The university is sticking with the resignation story, as is Patterson. Though he was happy to engage on any and all other questions, he declined to comment on what happened in the last few days of Brown’s tenure, which consisted of a series of conversations between himself, Brown, and UT-Austin president William Powers. Many insiders believe that Powers, under pressure from the board of regents, in effect gave Brown little choice other than to resign. As though to confirm that Brown left unwillingly, the university later announced that Brown would be paid a settlement that happened to be exactly what his contract stipulated he would be paid if he were to be fired: $2.75 million over four years.

But in the cool, quiet air inside the Escalade, there is no sense at all that Patterson arrived in the middle of a—what should we call it? A firestorm? An unfolding disaster? The temporary stumbling of a once dominant sports program? With Brown out, Patterson’s first job was to hire a football coach, perhaps the riskiest and most important decision an AD at a major university can make. He did so quickly and decisively, largely ignoring the handpicked search committee that was supposed to help him. He selected the University of Louisville’s Charlie Strong, who would be the first black head coach in Texas football history. Strong, however, was emphatically not at the top of many Texas boosters’ lists. One of the most powerful of those boosters, Red McCombs, who has given more than $100 million to the university and whose name adorns the business school, the north end of the football stadium, and the softball field, called Strong’s hiring, during an ESPN radio interview, “a kick in the face. . . . I don’t believe [he belongs] at what should be one of the three most powerful university programs in the world right now.” He added that UT—meaning Patterson—“went about it wrong and made the selection wrong.”

Patterson, who studied business as an undergraduate at UT before earning his JD at UT Law, was unfazed by the criticism. He was convinced he had found his man. “We looked at about thirty people initially and had serious conversations with six,” Patterson tells me as we head to San Antonio, where he happens to be having lunch with McCombs at his office later in the day. (The two have known each other for forty years, and McCombs has since recanted his remarks.) Patterson speaks with the trace of an accent that betrays his small-town Wisconsin roots. “With Charlie, it was a little different. When you interview somebody, you usually do it in your office, in their office, or maybe a hotel or a restaurant. With Charlie it was ‘Why don’t you come over to the house? I want you to meet my wife and family.’ So I flew up to Louisville and spent four hours in his kitchen with his wife and kids. He was exactly what I wanted. Tough, good recruiter, cares a lot about academics, and can deal with donors, alums, media, and all the constituencies he has to deal with.”

Patterson knows how crucial Strong will be. In November 2008 I wrote a cover story for Texas Monthly with the headline “Longhorns Inc.: How UT Built the Most Successful College Sports Program of All Time.” The premise was unchallengeable back then. Without Brown the success would not have been possible. Today, much of Patterson’s own success rests on Strong’s shoulders, which is why we are driving to San Antonio to attend a stop on the “Comin’ on Strong Tour,” an idea the marketing department came up with to introduce the new coach to the state.

A longtime assistant coach at Florida, Strong became head coach at the University of Louisville in 2009. He built his team into a national powerhouse, going 23-3 over the past two years and doing it with often-unheralded players who both behaved themselves and completed their degrees. He arrived in Texas with a blunt message: Texas players—criticized in the past by Longhorns fans as “too soft”—were in for a major cultural overhaul. Under the new regime, players would live in dorms on campus, not scattered around Austin in apartments. (Seniors with certain GPA levels may be exempt.) They would eat together and there would be “no cliques.” They would no longer enjoy the luxury of a special bus to take them to the air-conditioned indoor practice field. They would not wear earrings in the football facilities. Players would not only attend all classes but sit in the front two rows. Players who missed class would run until it hurt. On the second infraction their entire position unit would run—and on the third their position coaches would run. And, oh yes, there would be no “rebuilding.” The team would be expected to win now. “There’s no time for a rebuild,” he was quoted as saying. But he was also more than happy to tell alumni and boosters exactly how far he thought the team could go. “Right now we won’t be in the national championship game,” he placidly told a crowd in Dallas. When later challenged about the remark, he added, “A lot of times people don’t like to hear the truth.” The message was clear: there would be no pumped-up expectations and no entitlement under Strong. The boys would have to earn whatever they got.

By the time Patterson and I arrive in San Antonio, the event is in full cry. The cheerleaders jump and pirouette, Smokey the Cannon booms away, an alumni band plays Texas songs, and the orange-clad crowd sings along. There is plenty of Mexican food, a thirty-foot inflated Hook ’em sign, and a pantheon of current and former Texas coaches and athletes revving up the crowd. Strong, a big man with a big smile, looks happy and confident. He speaks in a rapid-fire cadence that is the antithesis of Brown’s honeyed Tennessee drawl. “I have an unbelievable job and a lot of support from both the academic side of the university and the athletic side,” he tells the crowd. “When you are in the top one percent of one percent, you expect pressure, and I welcome the challenge.” While there is something weirdly disorienting about watching Strong flash the Hook ’em sign, the crowd erupts in loud cheers. Brown’s name comes up once or twice, briefly and respectfully—his final, dismal loss to Oregon in the Alamo Bowl in December occurred about four hundred yards from here—but the crowd seems focused on the future.

Though Patterson arrived at a time of turmoil, he also walked into one of the best jobs in American sports. Maybe the best. He will make $1.4 million a year, a threefold increase from his salary at Arizona State. With its $165 million budget this year, Texas is by far the richest collegiate sports program in the country. Last year Forbes named UT—in spite of its troubles—the most valuable college athletics program in the nation, based on its success in ticket sales, licensing and merchandising, sponsorships, media rights, and fund-raising. Of course, it is also true that the pressure to win at the University of Texas is unrelenting, and the stakes are far higher than they have ever been. When Brown arrived, in 1997, UT’s entire budget for athletics was $21 million. In 2014 the debt alone is $242 million. Dodds and Brown, in effect, created a ravenous beast that must now be fed. These days failure is not a financial option.

Since no college in history has ever run a sports program on this financial scale, it is appropriate that the man hired to run it comes from the hard-edged, unsentimental world of professional sports. Patterson was the product of a national search for someone who could not only produce the wins and uphold the ethical and academic standards of the Dodds era but also understand sports finance. “He was the only one from professional sports who made it to the finals,” says Pamela Willeford, a former president of the Texas Exes and onetime ambassador to Switzerland who served on the search committee. “Integrity was extremely important to us, but we liked that he had so much experience in running enterprises, marketing, branding, facilities development.”

Though Patterson’s previous job was a seventeen-month stint as athletics director at Arizona State, he has spent nearly his entire career in the pros. He first entered that world through his father, a certified icon in professional sports. A basketball star at the University of Wisconsin, Ray Patterson managed to steal Steve’s mother, Ruth, away from football legend Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch. Ray became the president of the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks in 1968 and won a championship in 1971 with a team that featured Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Oscar Robertson. In 1972 he moved his family, including his fourteen-year-old son, to Houston to become the general manager of the Houston Rockets. Steve worked for his father during the summer and eventually joined the Rockets’ organization, where the two had a happy and productive partnership. Their lineups featured the “Twin Towers,” Ralph Sampson and Hakeem Olajuwon, and they mounted a successful bid to host the 1989 NBA All-Star Game at the Astrodome, which drew 44,735 fans, setting an all-time NBA attendance record that stood for 21 years.

At the age of 32, Patterson succeeded his father as general manager of the Rockets. As the youngest GM in the league, he quickly came of age in the NBA’s school of hard knocks. In 1992 he was embroiled in a public feud with Olajuwon over whether the superstar was well enough to play after an injury. “I don’t care if Hakeem doesn’t like me,” Patterson told the Houston Chronicle after being blasted by Olajuwon. “I don’t expect him to like me.” Patterson became the architect of the Rockets teams that won back-to-back NBA titles under Rudy Tomjanovich. Unfortunately, Patterson was not around long enough to enjoy them. In 1993 he was fired by new owner Les Alexander. “I wasn’t his own guy,” says Patterson.

Patterson’s greatest success in Houston came with Bob McNair’s NFL expansion group. He helped bring the Texans to Houston and cobbled together the remarkable public and private sector coalition that built Reliant Stadium. But Patterson faced a real trial by fire in 2003, when he became president of the NBA’s Portland Trail Blazers. Patterson, who was hired by billionaire owner Paul Allen to run the team, encountered a far worse situation than he would face at Texas. At the time he was hired, members of the team were being arrested so frequently that the team became known as the “Jail Blazers.” The team was losing an average of $33 million a year. Patterson responded by firing more than one hundred people.

“I had no choice,” he says. “The finances were not sustainable. There was no other way.” He also got rid of the team’s unsavory elements. Unfortunately some of them—like Rasheed Wallace, who was once suspended for threatening an official after a game—happened to also be immensely talented players, and their departure resulted in the team’s posting the worst record in the NBA. Nothing was easy. Patterson feuded with the media and lost in a very public bid to renegotiate the debt on the team’s stadium, the Rose Garden. In the newspapers, he was often referred to as the Trail Blazers’ “embattled” president.

But he persisted. Over a four-year period he cut the team’s financial losses by more than $70 million. During the 2006 draft, he set an NBA record with a dizzying six draft-day trades and produced a superb class of rookies who would soon turn the team’s fortunes around. Yet here too Patterson was not around to enjoy the fruits of his labor. He resigned in 2007 after his contract was not renewed, but it wasn’t long before Arizona State came calling.

Winning and making sure UT’s revenues stay ahead of those of competitors like Ohio State, Florida, Michigan, and Alabama are things Patterson must do to keep his job. His biggest challenge in his first years, however, may well have nothing to do with how his teams perform.

The sports world is engaged in a contentious debate over the issue of paying student-athletes. It is no secret that they generate huge revenues for colleges but get no cut of the profits. Meanwhile, universities who pay executives and coaches record salaries—Charlie Strong is in the $5 million–plus range—stand accused of the “systematic, ongoing, prolonged abuse of thousands and thousands of innocent young men and women,” in the words of Illinois congressman Bobby Rush. The NCAA and its members have recently faced an endless barrage of complaints, and the critics are abetted by recent studies, such as the one conducted by the National College Players Association, showing the purported “fair market value” of players. For a Texas football player, that would be $567,922. The study also showed that the average full athletic scholarship fell $3,285 per year short of covering the actual cost of college attendance.

The issue has coalesced in a wave of lawsuits that challenge the very nature of the NCAA’s amateurism model. One led to a ruling in March by the National Labor Relations Board that Northwestern University football players are employees and have the right to unionize. Though the case is being appealed, college athletics is collectively holding its breath. If the ruling is sustained, similar cases, with major union support, will likely be brought against public schools like Texas. Another alleges that universities deliberately set limits on scholarships, which fall below the actual cost of attendance, and yet another argues that colleges unfairly make billions off athletes’ likenesses without compensating them.

With the largest budget in college sports, Texas is perhaps the preeminent example of collegiate amateurism in America. One might not expect Patterson, with his largely professional sports background, to voice passionate opinions on this subject. But at a time when many NCAA officials are running for cover, he is one of the few major college ADs publicly defending the current system.

“We have allowed ourselves to be trapped,” he says. “All of us, the NCAA, colleges, coaches, and athletics directors. We have done a very poor job of talking about what college athletics really is all about for the 99.5 percent of student-athletes who will never play professional sports. We have allowed ourselves to have a discussion about that half percent.” He points out that athletes who make it to the pros have an average playing career of only four years. “They have a half century ahead of them after they are done playing,” he says.

Patterson’s argument begins with his conviction that both the scholarship and the college degree are enormous benefits to student-athletes, many of whom would not have gone to college otherwise. “I don’t think college athletes are the equivalent of minor-league football players,” he says. “They are students who wouldn’t get into the university but for the athletics and wouldn’t stay in the university but for the sports. If you look at them as a group, approximately eighty percent of them are the first in their families to go to college. In American colleges in general that group has about a fifteen percent graduation rate. With athletes, the rate jumps to between seventy-five and eighty percent. That is because of the resources the university puts toward helping them.” At the University of Texas, the tuition, room, board, books, fees, and other support in a scholarship are worth an average of $65,000 a year. “That is more than the average household income in the United States,” he says. “I don’t see how they are being shorted.”

But what about athletes like Vince Young and Johnny Manziel, who create huge benefits and revenues for their universities, from fund-raising to ticket sales to sponsorships and licensing? Shouldn’t they at least be allowed to monetize their famous names? “No,” he says categorically. “I am not saying they did not benefit the university. But you have to understand that both parties benefit. The university is largely creating the value. The athletes are trading on the value the universities have created. No corporations are going to be lining up to pay them money out of high school. They also get a huge benefit on the college stage by having such assets as strength coaches, nutritionists, psychological support, tutors, mentors, media training. All of that costs money. It is too easy for those in the sports press to say, ‘You are manipulating and using these kids. You are giving them nothing.’ We are not giving them nothing.”

There are also practical problems with paying athletes, Patterson says. He suggests that if schools pay Young or Manziel, they are going to be sued by athletes on the soccer or basketball or rowing teams, looking for equal pay. “That would almost certainly happen,” he says. “And if you have a situation where the students are employees, you will have to either hugely increase revenues or cut costs and eliminate teams.”

Patterson insists, at the same time, that he is not opposed to high school students’ turning pro immediately. It’s just that he thinks it is usually a poor option. He cites baseball as an example. “If you want to go to the minor leagues, ride the bus from Biloxi to Beloit and sleep in a Motel 6 and not have nutritionists, tutors, trainers, strength coaches, and everybody else who works with you at UT, if you think that is a better deal, God bless you, go do it,” he says. “I personally think it’s a better deal to come to UT and get a degree, even with Augie screaming at you for four years.”

DeLoss Dodds was fond of saying that at the University of Texas, no one worries about keeping up with the Joneses. “We are the Joneses,” he said. Other schools flirted with financial ruin to keep up. Indeed, it can be said that Texas’s spectacular success has had a destabilizing effect on college sports in general. Its athletics program is one of the dozen or so in the country that is entirely self-supporting—even to the point of returning millions to the academic side—while at most schools, sports and their pricey facilities are a massive drain on university revenues.

It has thus been enormously gratifying for Texas’s enemies to watch its teams struggle. It was fun to cluck over the football team’s failure to recruit three successive Heisman Trophy winners—Baylor’s Robert Griffin III, A&M’s Johnny Manziel, and Florida State’s Jameis Winston—all of whom wanted to wear burnt orange. It was fun to snicker this spring as UT, for the first time in 77 years, failed to have any of its players drafted by the NFL, while the spurned Garrett Gilbert, who eventually left UT to play for SMU, was chosen by the St. Louis Rams. But as rewarding as such schadenfreudehas been, it is likely to be a very short-lived entertainment.

The fact is, though UT athletics has certainly gone through a bad cycle—something programs like Alabama and Notre Dame know about—and though the pressure to win in everything from rowing to softball to soccer to golf is greater than ever, in most ways the future of the program Patterson has inherited seems dazzlingly bright. The evidence for this starts with UT’s financial performance during the four years when its revenue sports took a dive. You would think that, with a nasty recession that clobbered portfolios and drastically reduced giving across the country, fund-raising would be down. You would think that, based on mediocre performance on the field and court, ticket sales would be down. You might even suspect that Texas was about to have trouble paying down the whopping debt it acquired to pay for the renovation of its stadiums.

But none of those things happened. Ticket sales are up 11 percent since the recession. Contributions have held steady since 2008–2009 at $37 million and even showed a small increase, to a record $41 million, in 2011–2012. More significantly, during the five-year period from 2008 to 2013, overall UT sports revenue increased by nearly 20 percent, from a nation-leading $139 million to a nation-leading $166 million (total sports revenue at Texas A&M during 2012–2013 was $85 million). Today no other school in the country even comes close to Texas’s $332,000 per capita expenditure—the overall budget divided by the school’s five hundred athletes. “Steve has inherited a cash-flow machine,” says UT alumnus Mike Myers, for whom the track stadium and soccer field is named. “We haven’t been great, but the money has not fallen off a cliff. I would say, yes, that is bad news for our opponents. We have an incredibly powerful engine.” It is an engine whose investment and financial strategy has been fundamentally conservative. “We planned for stability,” says Chris Plonsky, the women’s athletics director. “We did things like putting people on three- to seven-year leases when the north end zone of Darrell K Royal–Texas Memorial Stadium opened. So we had a long-term guarantee of revenue. We had new television revenues that came in at just the right time.” In simpler terms, that means the debt can be easily paid down.

Then there is the much-maligned Longhorn Network, which is in fact one of the most glittering gems of the Dodds legacy. Though it gained initial infamy as the reason many Texas fans could not watch certain Longhorns football games on television and was seen by many as a failure because its principal owner, ESPN, could not come to terms with the companies that distribute television to customers, LHN is a potent asset. The University of Texas is the only college with its own network, and according to ESPN president John Skipper, it is the only school that will ever have such a network. “I don’t think you are going to see anybody else come behind them,” Skipper says.

What does Texas get out of it? An exclusive twenty-year contract with ESPN that will pay the Longhorns $300 million. An Austin-based studio with seventy employees that broadcasts two hundred athletic and academic events a year to 25 million households. A recruiting tool that no one else has. Imagine parents who live on the West Coast being able to watch their daughter play tennis on a high-quality broadcast without leaving home. Imagine a soccer recruit watching in-depth profiles of current players. Says Rick Burton, a sports management professor at Syracuse University who has worked with Nike and taught at the University of Oregon: “Texas changed all the rules when it signed an individual college deal with ESPN, just as Notre Dame changed all the rules when it signed an exclusive deal with NBC in 1991.” And like Notre Dame, UT might be the last college ever to have such an opportunity. As much as anything else, LHN guarantees a huge, long-term revenue stream.

“All of our finances are on a more stable footing now,” says President Powers. “The conference is stable, and therefore television revenues are stable. We have the LHN and it has distribution. We went through the challenge of conference realignment; I think that is behind us. We now have a very stable conference, and it’s stronger than I have seen it in eight years.”

To all of that must be added the performance of Texas’s teams themselves. Since Patterson’s arrival in November, baseball and basketball have turned themselves around. Rick Barnes’s team finished a strong third in the Big 12 after being picked to finish eighth and made it to the third round of the NCAA tournament. Most of its talented young team is returning, along with a top-ten national prospect, the six-foot-eleven-inch freshman Myles Turner. The baseball team finished third at the College World Series this spring. Last year volleyball made the Final Four and softball returned to the College World Series. Men’s swimming and diving finished second in the NCAAs this year. All that money buys the best facilities and the best coaches, who continue to draw top recruits. Texas remains stacked with world-class athletes.

Its sports programs also remain insatiable spenders of cash. Though a $166 million sports budget is beyond the wildest dreams of the vast majority of schools, that figure will not be enough to cover Texas’s growing needs. “We’re going to have to be north of two hundred million dollars soon enough,” Patterson says, citing a number that would make eyeballs pop out of heads at most colleges. What does he conceivably need that much money for? Well, there is the coaching transition from Brown to Strong, which will cost $7 million or more. There is the new tennis facility to be built on the intramural fields for $15 million. There is the expansion of the south end zone at Royal-Memorial, which Patterson is studying now and which could cost $100 million or more. There is the replacement for the Frank Erwin Center basketball and special events arena, which might be needed in five or six years, at a cost of more than $200 million. And there is the possibility that, if the NCAA allows it, schools from the five major conferences will increase the value of their scholarships to more closely match the cost of attendance—perhaps by an additional $3,000 or more per athlete per year. That will add untold millions in the future.

Keeping pace with these additional cash demands is, in effect, the baseline of Patterson’s job. “This is what Steve is really good at,” says Plonsky. “You are always about where you are from, and he comes from the entrepreneurial side because of his NBA and NFL experience. He has had experience with building buildings, naming rights, private and public partnerships, so he sees the world a little differently.” Patterson has said that he plans to greatly expand UT’s relationship with its sponsors, along the lines of what he did with his professional teams. This means a lot more commercialization of everything related to UT sports. Fortunately the Texas community loves the idea of signage everywhere (unlike, say, Stanford, which hates it). For Orangebloods, there is nothing better than a giant Godzillatron jammed with the names of corporate sponsors floating above a sea of burnt orange. (The aging Godzillatron will soon have to be replaced too.)

Though Patterson has only modest experience with fund-raising, this is the area in which he may make his biggest mark. Under Dodds, UT focused on building stadiums and arenas and on tying much of the fund-raising to the purchase of seats, club seats, and boxes. While all of that will continue as before, Patterson is already focused on what he calls the “Stanford model” of fund-raising, essentially creating endowments to fund individual sports and scholarships rather than raising money for bricks and mortar. Right now Texas has a mere $17 million in endowments for the various sports, third in the Big 12, less than half of A&M’s $70 million and far behind Stanford’s $500 million. “DeLoss’s view was, we have tremendous interest in football and we can get a better return on our investment if a donation goes into the stadium as opposed to an endowment,” says Patterson. “But at some point you start getting to the outside edge of it. How many suites can you build?”

That means raising money for the sports that do not generate revenue—everything except football, men’s basketball, and baseball—with the goal of making them self-sufficient. “I want to take each team and look at it as a separate enterprise,” says Patterson. “How can we create a model that makes the golf team self-sustaining? The endowment of our fantastic women’s track and field program is zero. I don’t think it should be zero.” (In fact, shortly before press time, Patterson and his wife, Jasmin Michael, signed the paperwork to endow a scholarship for the program themselves. In case you are interested, it costs $775,000 to endow a single full scholarship.) Currently the football team, which generated $109 million in revenue last year, supports those types of programs. But will Patterson succeed in squeezing more money from the faithful? “They won’t have any problem raising money at all,” says Myers. “They will be able to raise money as easily in the future as they have in the past.” Plonsky agrees: “We have had consultants come in here and look at us and say, with 450,000 living alumni, you guys haven’t even scratched the surface. We have never done true philanthropic fund-raising.”

Patterson is also interested in building what he calls the University of Texas’s “global brand.” This concept is light-years away from the old Southwest Conference, in which Texas was merely a regional power, whose name and reputation were largely confined to the state. Patterson, who became the first general manager to take an NBA team to Mexico (the Rockets), has international ambitions for Texas too. He has already booked the first basketball game of the 2015 season against the University of Washington in Shanghai, China, and is in the early stages of planning a football game in Mexico City. His idea is to try to link the sports contests with the interests of the larger university. “There are a lot of reasons to do this,” he says. “We have the opportunity to grow potential students, potential faculty members, business relationships between various schools on campus. Athletics drives tremendous viewership and interest around the planet. Notre Dame plays a football game in Ireland. UCLA has more than seventy retail shops in China. Athletics is the front door of the university, and if we don’t leverage the international opportunities, someone else will.”

If you listen to Patterson long enough, you realize that his job is really all about the brand: protecting it, nurturing it, expanding its reach. He also knows that his first decision could be his most important decision: hiring Strong. If the football team does well, then the rest of the pieces will fall into place. If not, his tenure could be rocky. In the short time that Strong has been on campus, he has already dismissed or suspended ten players for getting into legal trouble or for violating team rules. “My message to them is that we’re not going to become you,” Strong said. “You are going to become us.”

Yet Patterson is fortunate enough to be starting with what is already one of the best-known American institutions. “When you put up the biggest sports names in the world—Manchester United, the New York Yankees—the University of Texas is going to be on that list,” says marketing expert Burton. “The amount of coverage they generate, both domestically and, surprisingly, internationally, means that Steve has got to realize, ‘This is what Manchester United is doing globally, and we’re not doing anything. We have to be in that space.’ ” Lucky for Texas fans, that is exactly what Patterson is thinking.

- More About:

- Sports

- College Football