In 2014, Schlitterbahn’s Kansas City location opened what was thought to be one of the New Braunfels-based company’s crowning achievements: a 168-foot waterslide called “Verrückt” (a German word for “crazy”) that was, according to Guinness World Records, the tallest in the world. The opening was fraught. It was reported that test dummies went airborne after reaching the slide’s second hump—a claim the company denied at the time—and its debut was delayed multiple times, which Schlitterbahn said was because of an issue with the conveyor belt system on the seventeen-story ride.

After ten-year-old Caleb Schwab was decapitated on the ride in 2016, however, the hesitancy surrounding the ride turned out to be well founded. Schwab’s death was described at the time as a freak accident, but an indictment that came out of a Kansas City grand jury late in the day on Friday alleges that, while accidental, the rider’s death was less of a freak occurrence and more of an inevitability. According to a lifeguard who went to detectives after Schwab’s death, the company had altered reports from staff to hide the fact that more than a dozen people had been injured prior to the boy’s death. Schlitterbahn was indicted on charges including involuntary manslaughter, as was the local operations manager, Tyler Miles.

What does the indictment say?

The 47-page indictment is full of internal communications suggesting that rider safety was anything but a top priority when Verrückt was opening at the park. According to the indictment, lead designer John Schooley “possessed no engineering credential relevant to amusement ride design or safety,” and neither did Schlitterbahn co-owner Jeff Henry, whose emails describe a desire to “micro manage” the project because “speed is 100% required.”

What was the rush to open the ride?

According to the indictment, Henry proposed the ride to “impress producers of Travel Channel’s Xtreme Waterparks series.” In an email, he urged the swift pace on the ride’s development and construction because Verrückt was “a design product for TV,” requiring “a floor a day” on the ride’s construction. Schooley, meanwhile, wrote that “If we actually knew how to do this, and it could be done that easily, it wouldn’t be that spectacular.”

Was Schwab’s death the first time someone was injured on the ride?

No. According to the indictment, a seventeen-year-old lifeguard informed authorities that he’d been forced to amend reports detailing injuries suffered by other patrons who rode the Verrückt slide.

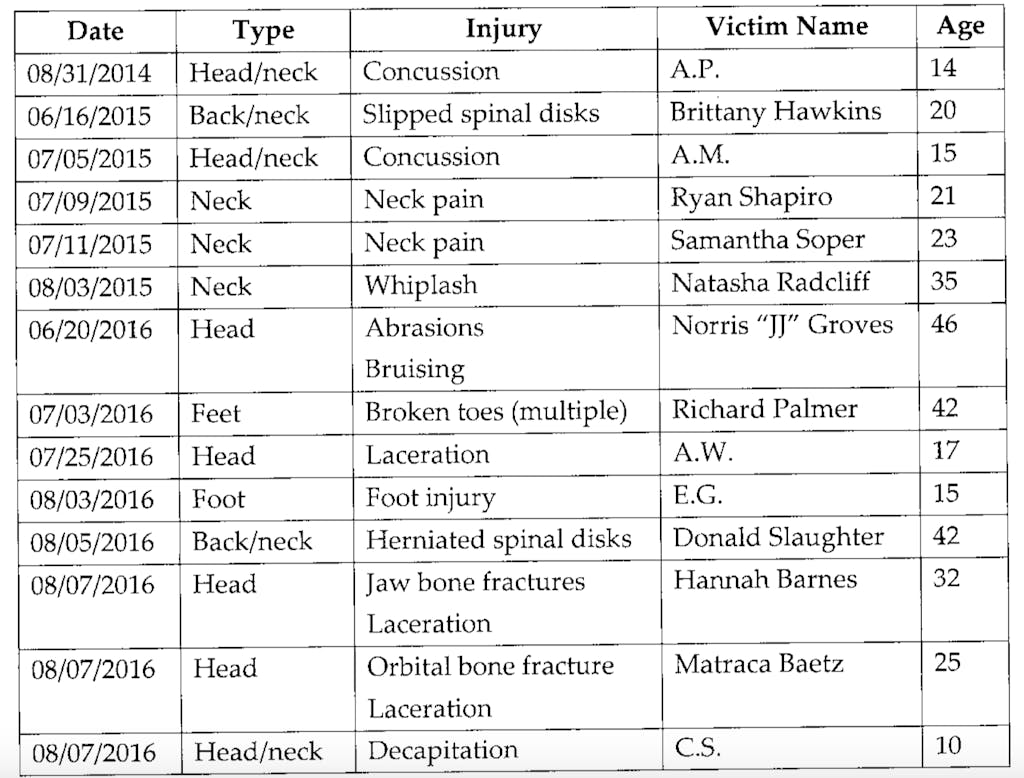

The indictment details fourteen injuries suffered by guests who rode the slide. The first report was of a fourteen-year-old’s concussion in 2014. Other injured riders included a 46-year-old man whose eye was swollen shut after his raft collided with a concrete wall (which led operations manager Miles, according to the indictment, to force medical staff to alter their reports), and the ten-year-old Schwab, whose injury is described in the document as “decapitation.”

What happened after the whistleblower went to police?

According to the indictment, after the lifeguard talked to police about the park’s attempt to cover up the injuries, an attorney for Schlitterbahn showed up unannounced at the young man’s house. The indictment says that the attorney told the teen’s mother that the investigating detective had requested her son turn over a copy of the report. She refused, and asked the attorney to leave; after he did, she called the detective and confirmed that he had made no such request.

Was there any indication that the ride was dangerous before it opened?

After reports that test dummies were being launched into the air, the company said that the ride was “not behaving properly,” but spokesman Layne Pitcher insisted that “I can tell you no test riders have gone airborne on the Verrückt.” However, the indictment alleges that Schooley and Henry began testing the ride at night to avoid people seeing what happened when they sent the sandbag test riders down the slide. Furthermore, some of their comments in the indictment seem to indicate that they were in over their heads. When asked why they didn’t have the design science down, Henry replied, “I’m not quite sure yet. Many things, I think. There’s a whole bunch of factors that creeped in on this one that we just didn’t know about. Obviously things do fall faster than Newton said.”

According to the indictment, Henry explained the danger presented by the ride in frank detail. The exact context of these statements was unclear from the indictment. After this story published, a representative from Schlitterbahn reached out to say that the quotes came out of “a reality TV show that was scripted for dramatic effect that in no way reflects the design and construction of the ride.” The statement continues, “Quotes were purported to be from definitive design meetings, when they were, in fact, ‘acting.’”

Regardless of the context, Henry’s statements as quoted in the indictment are troubling. “[Verrückt] could hurt me, it could kill me, it is a seriously dangerous piece of equipment today because there are things that we don’t know about it. Every day we learn more,” he’s quoted as saying. “I’ve seen what this one has done to the crash dummies and to the boats we sent down it. Ever since the prototype. And we had boats flying in the prototype too. It’s complex, it’s fast, it’s mean. If we mess up, it could be the end. I could die going down this ride.”

Did the passengers who were hurt follow the park’s safety guidelines?

According to the indictment, they did. The indictment also alleges that, prior to Verrückt’s opening, a consultant advised the company to set a minimum age of sixteen to ride; instead, they decided to print signs indicating that passengers had to be fourteen or older to ride Verrückt, but the day before the ride opened, struck that restriction and used stickers to cover the signs.

In the indictment, Henry seems to cast the industry’s guidelines as arbitrary and unnecessary—at one point, he’s quoted as saying, “we’re gonna redefine many of the definables that have been defined in the industry that we couldn’t find good reasons for. Like a 48-inch height rule. Why 48 inches? I could never figure out why not 47 inches. It made no sense to me. And so we’re gonna change all that now in this park, and hopefully change it worldwide in all parks and get back to rational reasonable scientific decisions as to why and how we run our facilities.” Furthermore, the indictment lists twelve different examples of the ride violating standards set by the American Society for Testing & Materials, which creates guidelines for amusement park rides. Schooley signed a document certifying that the ride was in compliance. The indictment describes the netting and support hoops above the ride as “obviously defective and ultimately lethal.”

Is it rare for a corporation to face criminal charges for manslaughter?

It is. Corporations, as legal entities, can be held responsible for criminal conduct. It doesn’t happen often, though, especially in cases involving crimes like homicide. (With crimes like fraud, as in the emissions case against Volkswagen, it’s less rare to see both executives and the corporation itself charged.) NYU law professor Jennifer Arlen explained the circumstances under which it can happen to Fortune in 2015, when asked if GM could be held criminally liable for deaths related to a faulty ignition switch. “First, prosecutors would have to be able to find a specific person whose actions led to people dying,” she said. “Second, that person would have to have taken those actions for the benefit of the company and within the scope of their employment, and have been ‘in the right mental state’ when they took the actions.”

What happens if Schlitterbahn is convicted?

Using the 2013 criminal case against BP in connection to the Deepwater Horizon explosion as an example (in which the company was charged with eleven counts of felony manslaughter), a corporation like Schlitterbahn is likely to face heavy fines and probation if convicted. BP was fined $4 billion—the largest criminal fine in the nation’s history—and given five years probation.

Have any executives been indicted?

The only individual named in the indictment was Miles, the 29-year-old former operations director at the park. However, on Monday afternoon, Henry was arrested in Cameron County. The indictment against him hasn’t been released yet, so it’s unclear exactly what charges he faces. His inmate page on the Cameron County website lists murder, twelve counts of aggravated battery, and five counts of aggravated endangerment of a child. Because the body that charged Henry is different from the one that made the arrest, though, we can’t confirm that the charge he faces is a murder charge. At this time, no other Schlitterbahn executives (nor lead designer Schooley) have been arrested.