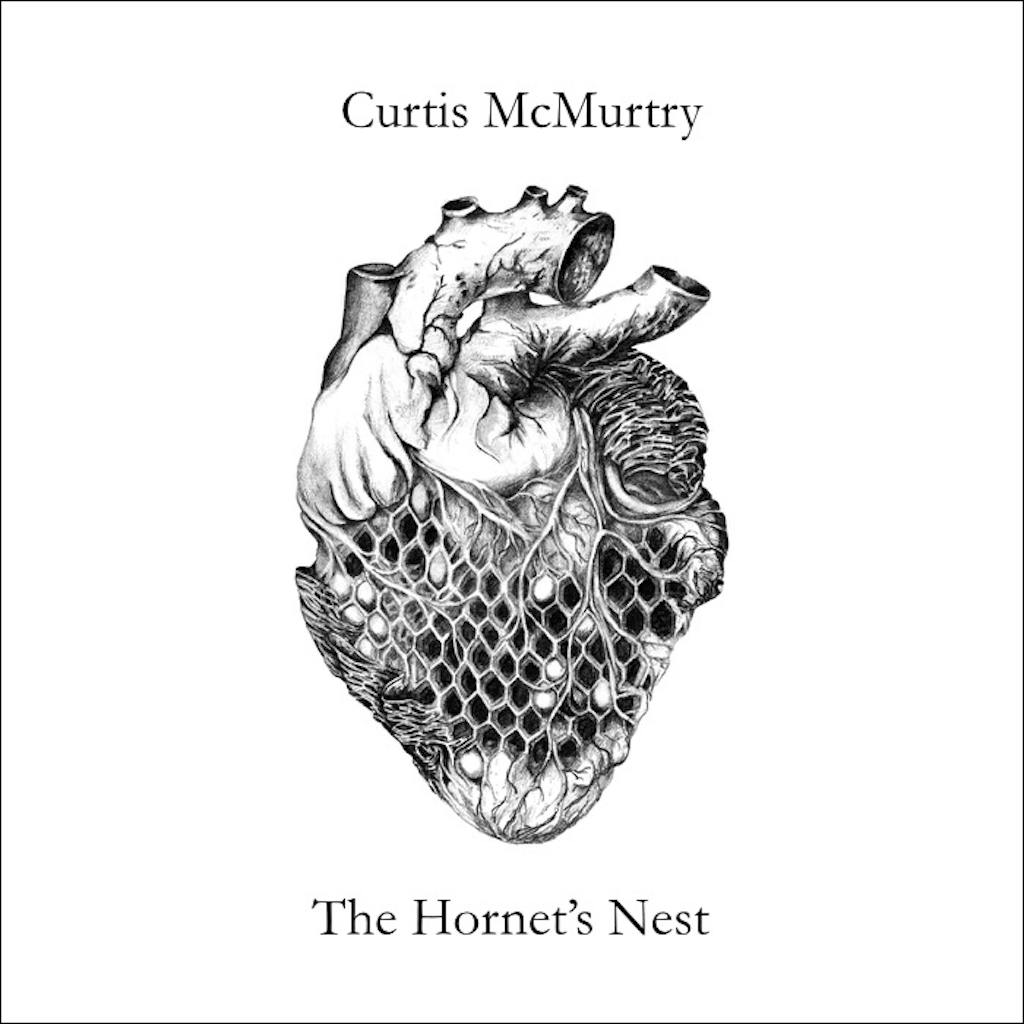

The loss of a child, and the subsequent collapse of a marriage as a result of it, is a harsh emotional terrain that few artists are willing to explore. Those who are able to successfully render such devastation into accessible artistic expression typically rank among our most serious auteurs such as Nick Cave. At 26, Curtis McMurtry could hardly be considered a seasoned veteran, but on his sophomore record, The Hornet’s Nest, the Austin-based singer-songwriter displays an aptitude for mining our bleakest, blackest moments to create music that challenges, provokes, and demands repeated listens.

McMurtry has not personally experienced the death of a child, but his character in “Bayonet” certainly has. Although the full story is never fully revealed, the suffering comes through in the elegiac tone of Diana Burgess’s cello (borrowed from Austin chamber-pop outfit Mother Falcon) and the lyrical glimpses into his world. “All that I’ve built us has worn down to rubble/Now all this rubble is all that we’re worth,” McMurtry sings in the last verse.

The sparse arrangement on “Bayonet” is consistent with the twelve other songs on The Hornet’s Nest, but elsewhere on the album McMurtry, who produced the album himself, makes use of Burgess’s wispy vocals to add a spectral harmony to his tenor. Also at the foreground on many of the tracks is Nathan Calzada’s muted trumpet, which often lends a back-alley early Tom Waits vibe to songs featuring the album’s seediest characters, such as the stalker on “Tracker.” The play between Burgess’s classical cello, Calzada’s jazzy trumpet, and McMurtry’s sprinkled-in banjo is a testament to the time McMurtry spent studying musical composition and ethnomusicology at Sarah Lawrence College in New York.

His unique musical palate makes neatly defining the album a fool’s errand. But those who are willing to follow McMurtry down the new path he’s forging will be rewarded. Yes, the subject matter can be unflinchingly grim (though not always) and the melody is often more haunting than bright, but each track is an opportunity to assume a different perspective that affords insight into the nature of loss and other dark corners of humanity we typically like to avoid. But once you’ve seen it through McMurtry’s gaze, it’s hard to look away.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Christian Wallace: The album has been described as a “sharply focused study of human relationships.” The songs are, more or less, thirteen different vignettes. Did you have a theme you were working toward from the beginning, or did you write them as you went and later tied them together musically?

Curtis McMurtry: Both, I would say. I’m frequently working with the same characters and the same sort of themes. I was thinking, or a lot of the characters on this record are thinking, about impermanence—about how nothing lasts, really. Love, relationships, life, work, legacy, any of that. And that means different things for different characters on the record. Some of them are completely at ease with the notion that they’re going to die, their bones will turn to dust, they’ll blow away, and no one will remember them. Some are completely opposite of that. There are a few songs on the record—“Bayonet” being one of them—that were pulled from other song cycles that I’ve written with the general theme of this one. [“Bayonet”] comes from a song cycle that I wrote in college about an older couple who had lost a child, and with that loss, all love and connection they had for each other. So, the character in “Bayonet” is dealing with both the loss of a child and the loss of a marriage.

CW: On your first album, Respectable Enemy, and again on Hornet’s Nest, you write from the perspective of characters who are not only contemplating impermanence, several are outright malevolent. What draws you to those kinds of figures?

CM: I think there’s an honesty to selfishness; that’s what draws me to it. If I can imagine someone in their darkest moment, when they’re feeling the most spiteful, the most self-absorbed, that can be easier to inhabit repeatedly. I think spite and selfishness are easier emotions to bottle than, say, love and happiness. It’s harder for me to really work and add depth to a character who is feeling overwhelming bliss.

CW: When I saw you and [Curtis’s father] James McMurtry at Strange Brew in December 2015, you played “Rebecca,” “Loves Me More,” and several other tracks from the new album. How long have you been working on these songs?

CM: Well, they were written across more than a few years. I recorded the album back in June, but then was on tour for most of the summer, so I couldn’t get back to mix and master it until the end of the summer/start of the fall. I got the masters back in October. A lot of people are more prolific than me, but I try to always be writing and crafting the next thing. I had a draft of The Hornet’s Nest before Respectable Enemy was out, but it can take me that long to get the funds together to get back in the studio and make something.

CW: I went back and listened to Respectable Enemy this week. Although it’s not overtly country, it’s definitely more Americana than Hornet’s Nest, which leans more toward the chamber ensemble sound. What made you decide to take a different musical route on this album?

CM: To be honest, this is the first [record] for a while that I was able to produce completely on my own. Respectable Enemy was co-produced with Will Sexton, who had more of an Americana idea for it. Admittedly, there was bit of a push-and-pull in terms of the sound on that record. Will wanted more of just me and guitar to court the Americana audience. While I was in agreement that that was a good way to go, I may have sabotaged it by needing to add strings and horns to everything because that’s the sound I wanted to chase. Getting to produce by myself this time allowed me to pursue the more chamber ensemble side of things. I got to cut loose without worrying too much about commercial stability.

CW: Tell me a little about the musicians you gathered for this album.

CM: Diana Burgess is all over this album. She’s incredible. She’s on the last record too, but, because I got to produce this one myself, I got to push her more to the forefront and put an actual duet on it. Diana’s incredible—amazing cellist, amazing vocalist. There’s also Taylor Turner, who plays upright bass throughout the record. Nathan Calzada plays trumpet. His inclusion was essential for me. It was really great trying to balance the jazz and classical elements between the cello and the trumpet, while also trying to make the statement that if Americana is just “three chords and the truth,” that erases so much music. It’s actually oppressive to decide that’s what Americana has to be. I think Americana is jazz. I think it is American and Western classical music. I think it’s everything that’s made here. The American myth is that we’re this melting pot; Americana should reflect that. I don’t feel it does currently. I think it has kind of a snippet of that, but this album—if anyone notices it—could be an argument for why Americana should be a bigger umbrella. Or maybe they’ll decide that Americana doesn’t mean that, that it essentially means guitar, bass, and drums. It’s a fascinating debate to me.

CW: Do you feel like there’s value in assigning that type of genre label to your sound?

CM: I think the point of genre is marketing, but I think Americana has—or at least the Americana Association, and by that I essentially mean the radio format—been inconsistent in a way that makes the term irrelevant. If both alt-country and, say, soul bands are Americana, but jazz is not, that doesn’t make sense to me. But when I look at the Americana Awards, that’s what I see. And in terms of gender, in terms of race, in terms of sound, it’s hard to argue right now that Americana is that much more diverse than the mainstream national country that it claims to be an alternative to.

CW: You’re the grandson of Pulitzer-Prize winner Larry McMurtry and the son of singer-songwriter James McMurtry. How does your family legacy affect the way you approach your own career ?

CM: Honestly, I don’t think about their work that much in reference to my own. I kind of think whatever influences I’ve taken from them are already within me now, and that’s not something I consciously guard or push forward.

CW: You went to college in New York, spent a year writing songs in Nashville, and have since returned to Austin where you’ve been living and making records for the past two years. Why stay in Texas?

CM: It’s a good central place to travel from. You can do the East Coast and then come back, then go up do the West Coast and come back, then go up the middle. And it’s easier to play in Austin than it is in Nashville. It’s easy to get gigs in Nashville if you’re touring and just passing through, but it was really difficult to play a lot while I was living there. It’s easier if you’re a session musician. A pub will give residencies to bands of session musicians, but, for songwriters, you’re really pushing just to play open mics. In terms of number of venues, Austin is far superior to Nashville. That’s a big part of it. And also the food. Austin wins on food. If I’m fortunate enough to be traveling a lot, when I do come home, I want the food I like to be there.

CW: Amen. The last thing I wanted to ask you about, while you were living in Nashville you were mentored by Guy Clark. Since he passed away earlier this year, I was wondering if you have some thoughts on him you’d like to share?

CM: The first thing that springs to mind is he was way more kind to me than he needed to be. He was just very sweet to me, and I know he wasn’t that way to everyone. I’m not sure why he treated me so kindly, but he let me write some songs with him. It kind of worked where I would have to have the seed of the song, and Guy would either perk his ears up or not. That’s how, by process of elimination, we would discover what we were going to work on. The one that excited him the most—I had this song that was from the perspective of Lady Macbeth, or at least a character similar to her, and that was the one that Guy really got into. By the time I knew Guy, he wasn’t in the best of health. He couldn’t play guitar that well. He was just kind of spinning between cigarettes and coffee. He needed his substances. He could still carry a conversation, but most of the time the cigarette was not going to leave his hand long enough for a guitar to be put into it. But for whatever reason he locked into the Lady Macbeth song and got really excited about it, and that was a wonderful feeling to have someone you look up to like that, to that extreme, really take an interest in one of your ideas.

The Hornet’s Nest is due out February 24, 2017.