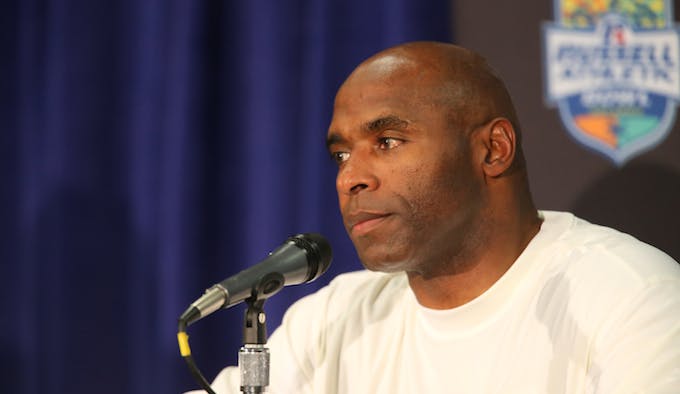

You’d think there would be a bit of cautious optimism as the Texas Longhorns head into another offseason under coach Charlie Strong.

Yes, the team is coming off its second losing season in a row, one marked by embarrassing defeats to TCU, Notre Dame, and Iowa State. But there were some bright spots in 2015. Remember the titanic upset over Oklahoma, the dispelling of Bill Snyder’s dark magic, and the victory over Baylor to end the season?

Even better, in most cases, the team’s youngest players were its best, Electric receiver John Burt hurdled defensive backs, Malik Jefferson wrecked shop in opposing backfields, and offensive linemen Connor Williams and Patrick Vahe cleared holes the size of Palo Duro Canyon for backs D’Onta Foreman and Chris Warren III. All of them, save for sophomore Foreman, are freshmen.

And yes, the quarterback position remains a huge question mark, but next year the Horns will have two experienced QBs competing against at least three more scholarship signal callers in spring practice, including blue-chip true freshman Shane Buechele.

But UT’s too busy fussing with its coaching staff. Shawn Watson, Strong’s right hand man from his Louisville days, was demoted as offensive coordinator after the team’s poor showing against Notre Dame and was let go last week. Joe Wickline, a wizard of teaching offensive line technique but reportedly a grumpy malcontent in all other facets of his job, was also released.

And it was in the tumultuous reeling in of their replacements—the Tulsa University duo of offensive coordinator Sterlin Gilbert and line coach Matt Mattox—that the Forty Acres revealed itself to be what it long has been, at least when the team isn’t contending for national championships year in and year out: a toxic stew of intrigue, backstabbing, treachery, and incompetence. And this time around, for the first time in UT coaching history.

The Gilbert hiring was tortuous and far more exciting than it needed to be. To recap briefly: last Thursday virtually every media source in Austin reported that Gilbert was in the bag, while sources in Tulsa were saying that wasn’t so. The next day, the Tulsa version won out. Gilbert was not coming to Austin, though sources vary as to why, with some claiming he had turned down UT’s offer (OMG things are so messed up even a Tulsa coach won’t come here anymore, went an oft-cried Internet lament), while others claimed that he not yet been offered at all.

We’ll likely never know exactly what happened, but at any rate, on Friday, a squad of Longhorn heavy hitters including Strong, newly minted athletic director Mike Perrin, and no less than the university President Gregory Fenves flew to Tulsa and got the deal done. The puff of white smoke coming from the Tower was not a mirage this time; the woeful offense of years past had its innovative young pope.

And yet you’d think the Horns had just suffered another Bob Stoops beat down if you spent some time in a few corners of the Longhorn Internet.

During and after all this drama, the fan blogs have been in a tizzy, most controversially in the form of reports by 247 Sports’s longtime Longhorn reporter Bobby Burton and an Inside Texas article co-authored by Eric Nahlin and Jesus Shuttlesworth.

Burton’s report essentially blamed Strong for the near-fiasco, claiming that the coach pulled a bait-and-switch by offering Gilbert a lowball contract offer not in keeping with what the Tulsa coach had been led to believe he would be getting. Perrin and Fenves had to bail him out, and the breakdown is just another sign of Charlie Strong being “in over his head,” as he is so often described. (“Deer in the headlights” is another fave of the anti-Strong crowd.)

Nahlin and Shuttlesworth are openly in the Strong-must-go camp, and while their report was ostensibly sympathetic to Strong the person if not Strong the football coach at Texas, it caused even more of a ruckus on the Forty. In short, they alleged that the Gilbert contract drama was engineered by a nefarious fifth column of boosters and athletic department insiders led by Mike Perrin himself, who, they allege, believes that “Strong needs to be gone after 2016 so Texas can get on with the business of winning.”

And so, they claim, Perrin passively interfered with Strong’s attempt to hire TCU’s Sonny Cumbie and Gilbert both by making himself scarce at Ricky Williams’s College Football Hall of Fame induction ceremony when Strong needed him most. Inside Texas further alleges that Perrin’s athletic department is leak-filled with his approval (one example: that persistent rumor that it might be best for all parties if Strong left for a “soft landing” in Miami), and that Perrin wanted Strong to fail in his contract negotiations with both Cumbie and Gilbert so he could put it down as a black mark against him in his work performance record, and so on.

It gets even more Machiavellian after that.

As someone who is privy to how the sausage is made, why not just fire the guy if you’re going to allow a drip, drip, drip of bad news in the program including but not limited to the clown show that was the offensive coordinator hiring process? The answer simply is that the Texas program and specifically the athletic director think the biggest risk for the program is to win nine football games next season. It’s sad but true.

Got that? The worst nightmare is a nine-win season next year, and they are doing everything they can to stop such a hellish scenario from unfolding. Apparently, this possibly nonexistent cabal believes that is Strong’s plateau—good, but not “Texas good.” (If so, they conveniently forget that Mack Brown didn’t break ten until his fourth season, despite inheriting a wealth of talent from John Mackovic.)

On the face of it, that’s a little tin-foil hat even for me, but if you look back through Longhorn history, such a move is not without precedent.

You know that old saying about mediocre teams: the most popular man on campus is the second-string quarterback, the guy waiting in the wings to turn it all around.

For others, the kind of people who write checks with a half-dozen or so zeroes on them, the most popular man is not on campus at all, but some trendy coach at another school. And in this case, that man is most often said to be University of Houston coach Tom Herman, strongly rumored to be the anointed one should some powerful donors with anti-Strong agendas get their way. (Chip Kelly is another, while some deluded souls still pine for Nick Saban or Jon Gruden.)

Texas has a long history of donor meddling, going all the way back to shortly after the end of Darrell Royal’s long and glorious reign as coach. When Royal stepped down and assumed the role of athletic director in 1976, he and his faction wanted to anoint long-term assistant Mike Campbell as his successor.

As usual, personal and political beefs trumped football considerations. The anti-Royalists were led by Allan Shivers, a former Texas governor and chairman of the UT Board of Regents. Shivers hated the folksy Royal’s nascent cosmic cowboy leanings, his hanging out at Armadillo World Headquarters with Waylon and Willie and the boys. Shivers also never forgave Royal’s devotion to his foe LBJ, or his televised endorsement of a bank that competed with one Shivers ran. So the regent enlisted the support of another aging bigwig: Frank Erwin, another former board of regents chairman and the namesake of the Longhorns’ doomed basketball arena. The anti-Royalists had other ideas and won out in the end, bringing in Fred Akers over Royal’s objections.

Needless to say, things got a little tense. An athletic department divided against itself cannot stand. Looking back, it’s a little amazing even with all that interference—verging on outright sabotage—working against him, Akers was able to keep the Horns in the national title hunt off and on from 1977 to 1983. Royal left the program flush with talent in 1977, true enough, but Akers’s 1983 national title contending team was all his. Many a coach stepping into the shadow of a legend has done far worse than Akers; think of the parade of short-lived coaches who followed both Bear Bryant at Alabama and Bud Wilkinson at Oklahoma. And in the rare cases where it does work, such as the Bob Devaney-Tom Osborne handoff at Nebraska, there are often good feelings on both sides.

There was no such bonhomie between Akers and Royal, just as there is little apparent goodwill between Mack Brown and Charlie Strong (and less between partisans of the two camps).

At any rate, nothing short of a national title would satisfy Akers-haters, and his failure to win not one but two vital Cotton Bowls (and a string of losses in lesser bowls) was proof enough that he was not up for the job, no matter that he had gotten them close on several occasions. And though it’s true that Akers’ program was in a downward spiral after 1983, how much of that was his own doing, and how much was it that of the forces arrayed against him from within?

As Texas law school professor Charles Alan Wright put in near the end of Akers’s time on the Forty: “The question I don’t have the answer to, and I’m glad others get paid to find it, is whether the public controversy has destroyed his effectiveness.”

After two straight disappointing seasons, public controversy is again rife, this time in regards to Charlie Strong. Indeed, thanks to the ‘net, that controversy is now more public than ever, and in reading computer, iPad, and phone screens of chatter and anonymously-sourced reports over the last couple of weeks, it feels like 1986 all over again.

Check out these quotes from a preseason Houston Chronicle report from that year:

“I think Fred is going to have to win a minimum of nine games to have a chance to stay,” says Houston insurance man Fred Curry, a longtime Akers supporter. “The problem is if he wins nine games and stays, then wins only eight the next year, the same thing is going to happen again.”

“The situation is hopeless,” says one prominent UT alum. “Akers is gone. They’re just waiting for the right reason to do it.”

“I’m very concerned that we have a situation that is not reversible,” says an Akers supporter. “Anything short of 10-1 will have these people asking for his neck again. It’s incredible.”

Sound familiar?

Akers failed to win nine and was unceremoniously dumped that year, and the team would wander lost, a stranger to January national title hunts, every year from 1984 through 2004.

Which brings us to where we are now, with Strong in the Akers role and Brown as Royal. A few things have changed. Unlike the talent Royal left for Akers, Brown didn’t leave Strong with a mighty arsenal at his disposal, as even the most ardent anti-Strongite will admit. And unlike the last few years of the Akers regime, Strong is bringing blue-chip talent to campus.

But there’s another difference separating the Strong-Brown saga, one I’ll explore on Friday. Stay tuned.