The wealth of world-class venues and attentive audiences within Texas have made us a destination for performers both native to the state and from around the world. From time to time, we check in on these performances in “It Happened In Texas.” This time out, we caught Kendrick Lamar’s taping of an Austin City Limits taping at the Moody Theater in Austin on October 30th.

The list of capital-A Artists making important music in 2015 starts with rapper Kendrick Lamar. Pulling equally from the influence of John Coltrane and Bob Dylan, Kendrick Lamar’s music is making an impact on a level that few artists will ever achieve. His most recent album, To Pimp A Butterfly, is a sprawling masterpiece expressing difficult themes like self-doubt, black liberation, violence within the black community, and radical self-acceptance in a mélange of genres filtered through free jazz, funk, seventies AM soul, and pop with joyful abandon. In short, there aren’t two artists just like Kendrick Lamar right now, and that alone makes his appearance on Austin City Limits a hell of a get for the PBS institution.

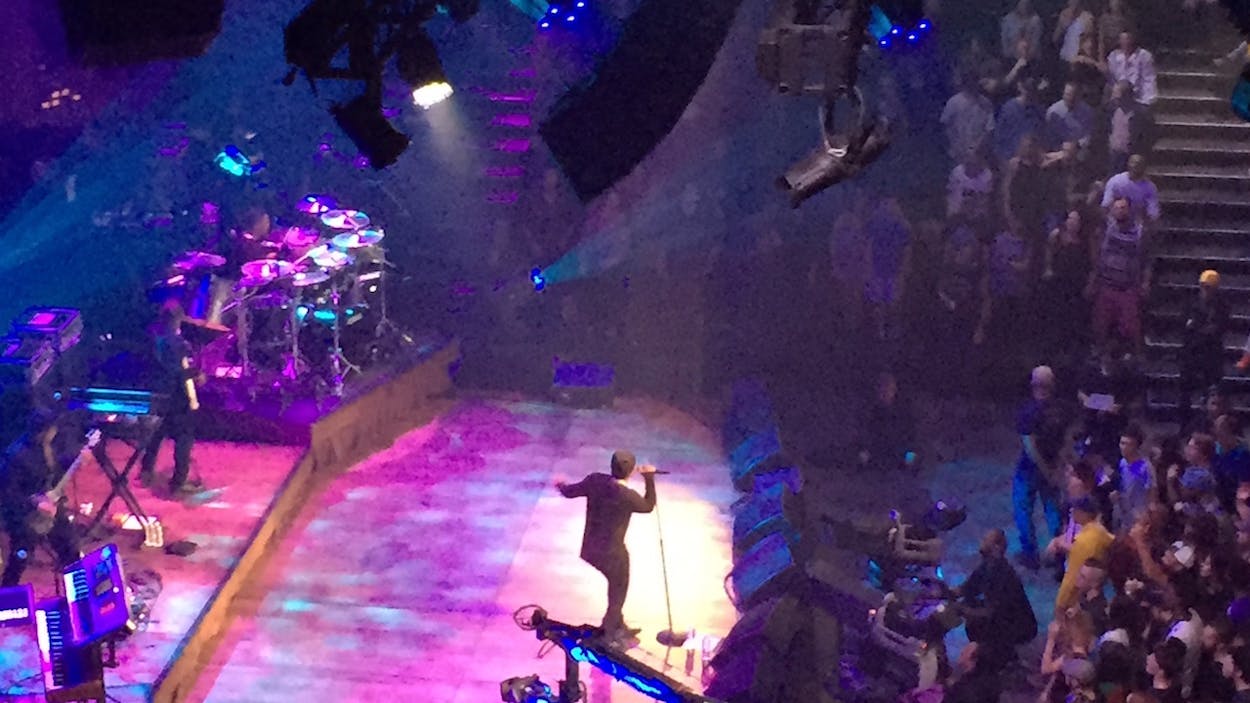

The Wesley Theory, a five-piece backing band consisting of guitar and bass, keyboards, drums, and a DJ, took the stage first, building the set’s opener, Butterfly standout “For Free? (Interlude),” to set the scene. Built around jazz drums and piano, the song saw Lamar standing in front of the mic stand like he was at a poetry slam, gesturing wildly as he recited verses about a record industry that sees young artists like himself as a resource to be exploited. It was a fine way to introduce Kendrick Lamar to a program that’s hosted fewer rappers than it has performances by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band—with an organic, coffeehouse-style sound that would have been downright palatable even to a hip hop averse crowd.

It wasn’t all jazz and poetry, though. The Austin City Limits set ran through an assortment of genres, even if they weren’t the same ones he explored on his latest record. A song like “Backseat Freestyle,” from Lamar’s 2012 breakout Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City, ditched the mainstream, radio-rap interpretation in favor of a heavy rap-rock sound (which didn’t alienate an audience that couldn’t wait to scream “All my life I want money and power” with Lamar during the choruses), while Butterfly‘s “U” and “Hood Politics” were reinterpreted with wild guitar solos as psychedelic freak outs. It all sounded authentic to the spirit of the songs. A track like “M.A.A.D. City” was always ready to play out as hard rock, but Lamar and his band played it loose enough to feel like they were reinvented on the spot.

It’s safe to say they weren’t, of course—the spirit may have been freewheeling, but the band was tight as any to grace the ACL stage. But as in control as the band seemed, Lamar was the dominant personality on the stage. Rappers often have a limited array of stage moves—going hard, pouring energy out to the crowd, running around the stage with the mic in their hand—but Lamar was much more interested in building his performance around true dynamics. Sometimes he was quiet; sometimes he was still; sometimes he bounded across the stage and shouted “Kendrick had a dreeeeeeeeam”; sometimes he raised his arms while his guitar player solo’d, demanding that the audience show their appreciation for what they were hearing, and then pointed those same arms toward the guitarist like he was channeling the crowd’s energy directly to the musician.

Lamar seemed genuinely overwhelmed at times by the enthusiasm of the audience. That appreciation was buoyed, perhaps, by recent reports that his current headlining tour has seen audiences leave after the opening sets by Fetty Wap, Meek Mill, and Future, all of whom saw recent records blow up to a fan base that’s fairly different from Lamar’s. Near the end of his set, a chant broke out—”We gon’ be alright,” the chorus from Butterfly‘s smash single “Alright,” and Lamar transformed himself from MC to orchestra conductor, roaming the stage to reach different sections of the audience and encourage them to do the chant louder, then softer, then louder, then softer again.

Still, it wasn’t without complications. The band blew out the stage’s monitors, which required an unexpected fifteen minute intermission. But that did little to dampen either the audience’s or Lamar’s enthusiasm for the proceedings, and though the flow of the set—which seemed tightly scripted to build an emotional swing from songs like the groove-based “Swimming Pools (Drank)” to the haunting, aggressive “The Blacker The Berry”—was momentarily disrupted, it just fed the improvisational spirit that makes Lamar such a special artist. There’s a feeling, seeing him perform in 2015, that can make a person wonder if that’s what it was like to see Coltrane at the height of his powers at the Village Vanguard, or to see Dylan in 1965 when he first started playing electric—the idea that this is a transformational artist, growing into the sort of musician who’s changing music with everything he records, is very real with Kendrick Lamar. With that in mind, there’s almost as much to savor in the imperfections as the impeccable execution of the well-rehearsed moments. It’s all real, it’s all authentic, and it’s all happening live and in front of you right now.