My dad’s shoulders heaved the way they do when he’s stifling laughter, trying not to make a sound. It was just after dawn this past December, and we’d been sitting in the deer blind for the better part of an hour, waiting for a buck to wander up to the feeder. On such mornings, we often whisper off-color jokes and quote our favorite movies to pass the time, and Dr. Strangelove references are a part of the routine: “You can’t fight in here. This is the War Room!” It gets Dad every time.

Soon enough, a broad-shouldered buck ambled innocently from a clearing in the cedar, and Dad grabbed his binoculars. He confirmed that the animal was at least three and a half, old enough to have enjoyed a couple of ruts, or breeding seasons. In other words, a shooter. I raised the .243 I’d recently borrowed from my stepbrother and carefully chambered a round. I tried to slow my breath, just like Dad had taught me. I waited for the stag to turn broadside, then closed my left eye and focused my right through the scope, aiming for the spot just below his shoulder blade, where I knew his heart to be. I pulled the trigger on an exhale, and when the gun went off, I realized I had forgotten to put in my earplugs.

It was my third or fourth attempt to bag a buck that season. Previous hunts had been thwarted by the usual variables to which the prospective deer killer is beholden. One November evening brought a good crowd, but I didn’t see a shooter, just a doe and a couple of playful yearlings. The next morning not a single mammal passed before me, merely a few birds that got my hopes up each time they flitted around and rustled a branch. Later that night I spotted a nice eight-pointer, but I was by myself and got nervous. Dad wasn’t there to verify the buck’s age. He has a better eye for such things, and neither of us wants to take the life of something young.

In the fifteen or so years I’ve been hunting whitetail, I have yet to pull the trigger without my father present. For a while the reasons for this were juridical. Before taking Texas Parks and Wildlife’s Hunter Education safety course when I was 29, I was permitted to hunt only if accompanied by and “within normal voice control” of a licensed-and-certified-in-Texas hunter like my dad. But even now that I can legally sit in a deer blind with just my rifle and my buck knife, I spend most of the weekends between early November and mid-January with him on our family’s ranch outside Brady.

During these trips, we fall into a familiar pattern. We set our alarms for 5:30 a.m., though I often oversleep before morning hunts, so Dad makes the coffee and readies the rifles. He fills a tote bag with ammo, binoculars, earplugs, a first aid kit, and whatever else we need for two hours in the elements. Once we’re dressed and sufficiently caffeinated, we gather our armaments and creep in silence to the truck, already practicing the care we’ll have to show once we’re in the presence of the skittish animals we’re hoping to kill.

Dad drives, and we plod along on a narrow dirt road flanked by prickly pear and choked with cedar, scanning the brush for the orange tape identifying the turnoff to whichever blind we’ve chosen to inhabit that day. The oldest of these blinds dates back to the nineties, but the land has been in our family for much longer, snatched up by my mom’s people sometime after they left Idaho for the Texas Hill Country, in the late 1870s. Once we’ve parked, we cautiously extract the rifles from the back seat, make the short walk to the blind, and climb inside. Even with just two of us, the blind is cramped, roughly a four-by-six box made of some combination of plastic, wood, or metal. There, we entertain ourselves as quietly as we can until the sun rises and the feeder goes off, dropping kernels of corn to lure our prey.

After one of us takes a shot, we give ourselves fifteen minutes to wait it out, allowing the animal sufficient time to die. Then we descend from our perch and track the wounded whitetail. When we find the body, one of us gets the truck and moves it closer, allowing for easier load-in once the field dressing is done. We each grab an end to flip the buck over. I usually hold on to the antlers, and Dad always reminds me to be careful—he has a persistent fear that his accident-prone daughter will drive the tines straight into her gut. With the animal’s legs thrust skyward, one of us pinches the skin above the groin, makes a cut, and slices slowly toward the sternum, careful not to puncture the organs inside. We both watch the blood and steam spill out into the winter air. At this point, it is not unusual for at least one of us to cry.

My father has never lived in the country but has always idealized what he refers to as “the arts and sciences of rural life.” This is something he inherited from his mother. My paternal grandma was born in the twenties, on a stretch of South Texas coastland that had been in the family since they sailed over from Essex, England, in the mid-nineteenth century. Her parents divorced when she was young, and she and her little sister lived out on that Calhoun County farm with their father, their “papaw,” and a smattering of uncles who spent the workless years of the Depression hunting for food on the old family homestead. Grandma had tan skin, a Scout Finch haircut, and calluses so thick the soles of her small feet were impenetrable to sticker burrs; she almost always wore overalls. Once, when her grammar school teacher asked the class if anyone could identify the four seasons, Grandma confidently spoke up: “Deer season, duck season, dove season, and prairie chicken season.”

Once, when her grammar school teacher asked the class if anyone could identify the four seasons, Grandma confidently spoke up: “Deer season, duck season, dove season, and prairie chicken season.

To my knowledge, my grandmother has never killed an animal for sport or for food, but she’s always loved men who do. She fell for my grandfather because he brought her out on hunts and fishing trips and didn’t waste her time on the frivolity of dance clubs like the other boys who had come calling. After they married, it was Grandpa who taught her younger half-brothers how to stalk a deer. (Their father, my great-grandfather, had apparently lost interest in the sport. He was the ambitious one in the family, and his favored hobby was acquiring land.) Grandma wanted a man who could provide, and my grandfather was the confident sportsman she decided to have children with. Their firstborn, my father, did not fall far from that tree.

By his own admission, Dad “was always prowling in the woods” near his childhood home in suburban St. Louis, where his family had settled after my grandfather’s tire business took them from South Texas to Alabama and Illinois and Missouri. Dad had a .22 and would while away hours of free time searching for rabbits and squirrels. When he bagged something, his mother always cooked it, no matter how small or how gross. While his little brother hoped for family vacations to Europe, Dad only ever wanted to go back to South Texas, to the family’s homestead in Port Lavaca, where he could roam the southern coastal prairie for a change.

“I’d give anything if we could get back [to Texas],” he wrote in a letter to the editor of Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine in 1966, when he was fourteen. “Every Christmas our family comes down to Port Lavaca, and my father and I go deer hunting. I’ve been twice, but I haven’t bagged one yet. But I will next year!” He was jealous that his step-grandmother, Ode, who was not the sort of woman to ever come home empty-handed, had taken down a buck when he still hadn’t got the one.

Dad killed his first deer the Christmas after he turned fifteen, just as he promised TPWD he would. He’d spent the morning alone in a South Texas tree stand, “freezing my ass off,” and had decided to call it a day. While walking home, an eight-pointer passed through his line of sight. He shot it with Ode’s .257, which he’d borrowed because his own .30-30 wasn’t scoped. When he found the body in the woods nearby, he dragged the animal to the road, laid down his rifle, and hightailed it back to the farmhouse to get his dad. On the way, he was spotted by my great-grandfather, who later relayed to everyone in the family, “I could tell right then that something either awfully good or awfully bad had happened.”

These days, when Dad tells the story of that first buck, he usually pauses between “there I found him” and “dead.” Fifty years later, it’s as if he still needs a moment to come to terms with the threshold he’d crossed. He hunted for a few more Christmases before graduating high school, joining the Marines, and spending just under a year as a radioman, calling in naval gunfire in Vietnam. He didn’t hunt for nearly a decade after that, distracted at first by repatriation, then college, then a burgeoning journalism career that took him from Livingston’s now-shuttered East Texas Eye to the business section of the Austin American-Statesman. When he was thirty, he met my mother at a house party just north of the UT campus.

Like my father, she was from a long line of Texans whose family had continued to congregate on the same patch of land for generations, even after they’d moved away. In Mom’s case, it was a ranch in the Hill Country, just outside her hometown of Brady. They fell in love, married, and had their first child, my brother, within two years. Sometime during this period, Dad began hunting again. After his tour in Vietnam, he’d had no interest in “creating loud, explosive noises as a recreational activity,” but he eased back into it by shooting dove with both of my grandfathers. By the time I came along, three years after my brother, he was a deer hunter again.

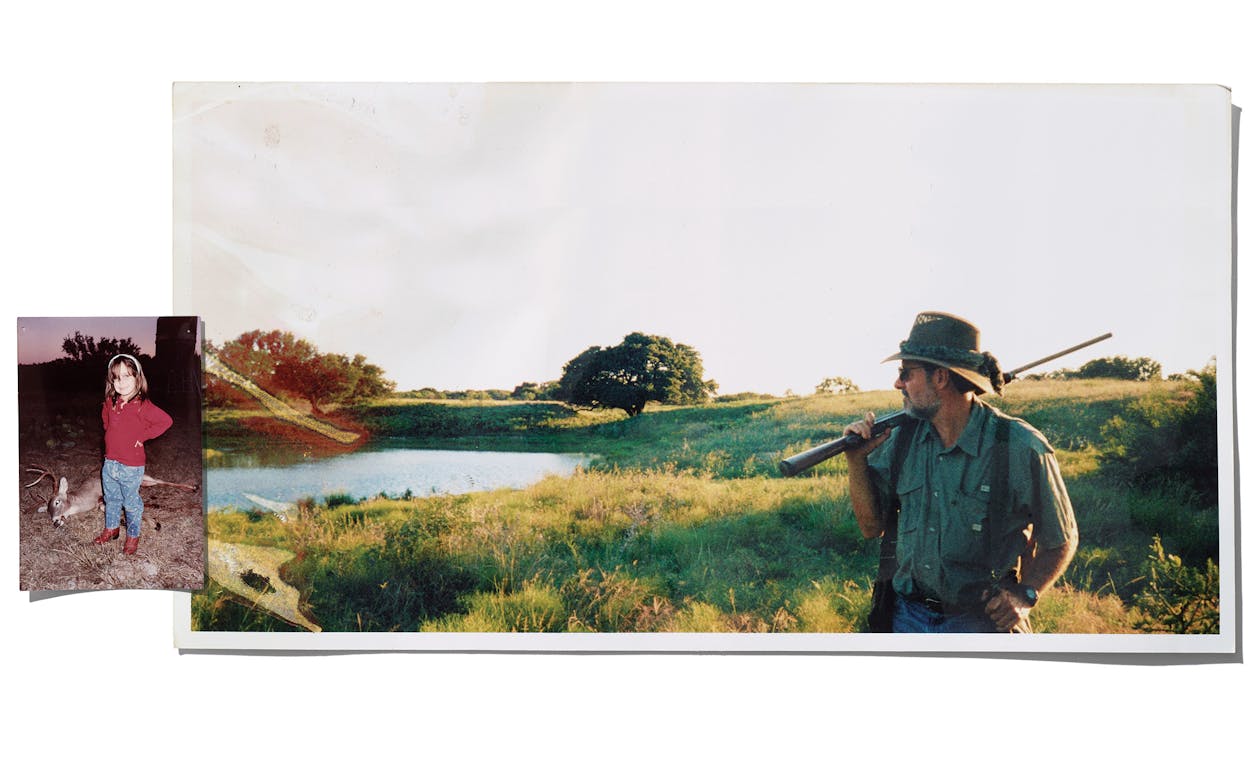

My maternal grandparents had passed by then, and my mother had inherited her portion of the family tract. Dad settled comfortably into the role of ranch patriarch. He raised his two kids around the same rural “arts and sciences” that had shaped his own childhood, and though we lived in Austin, we visited the ranch as often as we could. We were a hunting family, Dad made sure of it, and my earliest memories are of ranch trips, dead animals, and gamey meats. Nonetheless, I was fifteen the first time I joined my father in a deer blind and pulled a trigger.

Unlike my dad, I did not spend my childhood prowling the woods with a .22. The first time I ever sat in a deer blind there were no rifles present, just me, my mother, two pairs of binoculars, and some snacks. I must’ve been around seven at the time, and my dad and brother, David, were at a feeder the next pasture over, scoping for deer. We were out at the family spread. As I recall, Mom and I didn’t see any deer at our feeder that particular evening, just some feral hoglets. As the sun set, we met back up with the rest of the family, where we learned that my brother had been unsuccessful in his quest to bag his first buck but had managed to kill a boar.

We all piled into my grandfather’s old 1983 Suburban and headed back to my grandparents’ former home in town. My family had kept the car and the house after they passed, partly to use when we visited the ranch, but also because we’re not the kind of people who can easily let things go. I have many memories of riding in the Suburban down the highways leading in and out of Brady. It was clunky and tan and seemed colossal when I was small. My brother and I were allowed to unbuckle our seat belts as soon as we hit a dirt road. There was loose corn in the back and, on the front of the vehicle, a whitetail-size cargo carrier bolted to the brush guard. Trips to the ranch often ended with my parents up front, my brother and me riding in the back with the corn, and a slack-jawed, field-dressed deer carcass in the carrier. When we got to the house, Dad would hang the deer from a live oak outside the kitchen window to let the blood drain out. This was all “just part of the Brady routine,” my father would say. My earliest meditations on mortality came while I stared at the limp, gray tongues dangling from the mouths of those deer in my late grandparents’ backyard.

I loved spending time with my dad, so I often helped him clean his guns or change tires on the Suburban between hunting trips. There’s a photo of me as a toddler, kneeling curiously over the body of a dead buck, while my father stands nearby. I don’t look upset and likely wasn’t. I don’t remember being disturbed by the killing, and I know that I appreciated the spoils (my childhood breakfasts frequently featured venison sausage that had been made with a spice blend preferred by my paternal grandfather). But that was the extent of my participation.

As a family, “we” may have been hunters, but the women—outside of Ode, anyway—were not. My paternal grandmother and mother’s participation in the family pastime was limited to a little cooking and granting their husbands permission to pass down the activity to their sons. It wasn’t necessarily that I was discouraged from hunting because I was a girl. Rather, because I was a girl, I would be spared the burden of having to hunt, or at least of having to decide whether or not I wanted to.

My brother expressed interest in hunting around the age of eight. David loved shooting his Red Ryder BB gun in the backyard, so my father bought him his own shotgun, and they were soon scheduling weekend dove hunting trips. As my father tells it, David took to sportsmanship. At the tender age of eleven, he brought down an eight-point buck that had one of the widest spreads anyone in our family has ever bagged. But my brother’s hunting career was short-lived. He grew more interested in music and less interested in guns as the years progressed. He stopped hunting altogether when he was thirteen, around the time our mother lost her battle with breast cancer.

After her death, Dad took on more responsibilities at the ranch, just as Mom had done in the years following her own parents’ deaths. For our family, like many landowning families today, the bulk of the income that keeps us from having to sell comes from hunting leases. Dad worked with Mom’s brother (my uncle Bart) to manage the leases and oversee general maintenance. That first year, he went out to Brady regularly, while my brother and I stayed in Austin with our paternal grandmother. Dad told me later that, on these drives, he often lost himself in imaginary conversations with his dead wife.

His buddies persuaded him to go dove hunting the first season after Mom’s death, but he didn’t kill a deer for a couple years after that. When he eventually started hunting deer again, he usually went by himself, and when he bagged a buck, he’d have to take a break before he could begin field dressing his kill. He could never explain why, exactly.

But there are expectations for the Texas landowner, which my widowed father now found himself to be. This includes keeping up with yearly harvest recommendations necessary to curtail the population of deer, a species whose historical predators, like the black bear and gray wolf, were all but wiped out in the nineteenth century. And if you have developed a fondness for smoked deer sausage and chicken-fried venison cutlets, there’s only one way to get the meat. So Dad kept hunting.

A few years later, when I was twelve, Dad remarried, and my new stepbrother, Nick, who was eight at the time, expressed an interest in joining him. My father brought him to the ranch and taught him how to shoot one of my brother’s old guns. The kid killed a turkey on his first trip out and was soon obsessed. Had it been legal for a boy in the early aughts to prowl the Austin woods with a .22, Nick would’ve done so. He spent a season or so sitting in blinds next to my dad, then bagged a lean nine-pointer when he was nine or ten, which Dad had shoulder-mounted and hung next to David’s buck in the dining room of the ranch house.

Nick started joining my dad for dove hunts in the fall and deer hunts in the winter. Sometimes they’d invite Nick’s friends and their fathers out or just head to the ranch to pal around with the lease hunters, where they would grill burgers, play poker, and return home with inside jokes they claimed were inappropriate to share with us girls, which infuriated me. I’d never thought of myself as a young woman who needed sheltering, and I didn’t appreciate being left out of the joke.

My principal interests at the time were Agatha Christie books, Red Baron pizzas, and episodes of ER, but the thing that mattered most was my relationship with my father. When he took my stepbrother hunting, Dad wasn’t just teaching him marksmanship; he was teaching him how to be still, how to listen, how to be safe, how to provide, how to respect an animal’s life even when you’re taking it. I resented missing out on anything solely on the basis of gender, and I was terrified that someone might grow closer than I was to my only living parent. So, not long after I turned fifteen, I told my dad I wanted him to take me deer hunting.

The truth is, shooting a deer with a scoped rifle from a blind at a corn feeder is not, in itself, terribly difficult. You’re hidden, you’re seated, and you have a window ledge on which to rest your heavy gun. You’ve lured the animal to you in the easiest way imaginable. If you’re any good at playing Big Buck Hunter in a bar, you’re probably not half bad at the real thing.

But killing a deer quickly and humanely is a different story, and if you hunt deer long enough, you will inevitably fail at this endeavor. Dad told me early on that gruesomeness is just “part of the deer-hunting routine,” and my experiences soon confirmed as much. The first deer I killed—on only my second visit to a blind—was an easy one. I pointed, I shot, and that eleven-pointer dropped where he stood. A fount of blood spewed roughly four feet out of the entry wound. Another year, I foolishly—hubristically—decided to forgo the usual pre-hunt trip to the rifle range. I shot low and to the left, shattering my target’s two front legs. Dad had to put him out of his misery with the .45 he keeps on his hip for these kinds of worst-case scenarios, while I wept nearby. I still hope I never forgive myself.

For those first few years, I cried every time we walked from a blind to a body, which prompted my father to share his own mixed feelings about the macabre act we were participating in. He seemed close to tears himself sometimes but restrained his emotions by listing his reasons for sticking with the sport. Hunting reminded him of his childhood. It made him feel closer to his own father, who had died a few years after my mom. He felt a sense of stewardship for my mother’s land and a duty to manage its deer population. He liked the meat. His family liked the meat. It was nice to have a reason to sit outside, to watch the animals, to see the familiar cedar and mesquite turn strangely exotic when you start looking at them as habitat instead of just scenery. It was part of the Brady routine.

Despite my fondness for the time spent with Dad on the ranch, after high school graduation, I abandoned the sport for the better part of a decade, much like my father had in his teens and twenties. I went to New York City for college and even half-heartedly practiced vegetarianism for a couple semesters before coming to my senses. I moved to San Antonio, then Southern California, then back to New York. But Texas called me home. I missed my dad, and it was time to start helping take care of the ranch. I was eager to establish the routines that would define my own adult life in Texas. I returned to Austin in my late twenties, in 2013, this time for good.

Naturally, Dad and I headed to a deer blind the first November weekend after I moved back. It felt right to be there, on land passed down from one of my grandfathers, holding a rifle passed down from the other, and talking with my dad about them both. We settled into our familiar pattern, but it was more comfortable now that we were older. Dad’s instructions seemed less patronizing, my responses less disdainful (the last time I’d been in a blind, I was still in my angsty teen years, or as Dad calls them, “your miserable period”). “Don’t forget to take deep breaths,” he reminded me when an eight-pointer wandered out of the brush. “Squeeze the trigger on an exhale.” The buck dropped just a few yards from the feeder.

Nowadays, I set aside as many weekends as I can between early November and mid-January, because I don’t know how many trips it’ll take me to get a deer (or two, depending on how empty the freezer is that year). Sometimes I don’t see anything. Sometimes I see something too young to bring down. Sometimes I see a shooter but can’t get my hands to stop shaking, so I don’t pull the trigger. Occasionally I go it alone, and while waiting for the feeder to go off, I pass the time with books, cellphone games, Twitter, crossword puzzles, and unsuccessful attempts at silent meditation. But most of those mornings and evenings in deer blinds are spent with my father, talking about family, work, Dr. Strangelove, how much we love our dogs, which fences need replacing, and the reasons we’re still deer hunters even though it is devastatingly sad.

After taking a shot at the broad-shouldered stag last December, I was nervous. I was fairly certain I had hit him, but you can’t know how clean your shot is until you open the body up and see what you did to its insides. The buck had darted to his left after my shot rang out, and as I was scolding myself for not putting in earplugs, he disappeared into the brush. Adrenaline (and the instinct to survive) can propel deer quite far, even if they’re already more or less gone. Of course, it’s possible that I missed the buck entirely—I’d done so before and will do so again—though Dad assured me he didn’t think that was the case.

I would’ve been fine with a clean miss, just as long as it was clean. What I worried about, in those fifteen minutes we waited for the deer to bed down, was that I’d incapacitated the animal, hitting him in the leg or the shoulder, which meant he was hurt bad but was still very much alive and alert. I pictured him under a mesquite tree somewhere, unable to move but feeling everything. When the fifteen minutes passed, I leaned the .243 I’d borrowed from my stepbrother in the corner of the blind and climbed down the rickety metal ladder to the ground below. I looked back up at Dad, and he handed me the rifle, which I slung over my right shoulder, then passed me his .270, which I handed back to him once he’d safely dismounted. Dad, now 67, says he’ll keep hunting as long as he can physically get in and out of a deer blind, which he has found more difficult to do in recent seasons. I still can’t fathom what it’ll be like to shoot my first deer without him, and I’m not eager to do so.

We headed toward the brush to the right of the blind. We walked around for a few minutes, scanning the cedar and prickly pear. Thirty or so yards from the feeder, we found him, dead. The shot was clean. (“Thank God,” I whispered to myself.) We dragged him out of the pile of cactus into which he’d fallen, then dressed the body, loaded it into the bed of the pickup, and headed back to the house. We relaxed some on that return drive, relieved that we’d managed to bag one buck with a month and a half still left in the season. If Dad could get another deer, the family would be set, and we wouldn’t run out of the good sausage the way we had the year before.

My older brother, who still spends weekends with us at the ranch even though he no longer hunts, met us by the cleaning station when we pulled up to the house. Though he hasn’t wanted to kill a deer for over twenty years, he’s always down to help when one of us does. He has as much of a vested interest in our venison supply as the rest of us do, and he knows it’s easier for his six-foot-two frame to lift a 150-pound deer carcass than it is for my five-foot-five frame. We used a garden hose to wash out the body with water from the well, and when we removed the tarsal glands from the inside of the buck’s hind legs, Dad said something about not knowing if that was absolutely necessary but that he always did it this way because it’s what his father taught him. Then we pushed the ends of an iron hanger through the cartilage in the deer’s back knees, and my brother and dad hoisted the animal up to the A-frame, where he’d hang for the rest of the day until we moved him to a walk-in cooler.

By the time we were done, I needed another cup of coffee, and all three of us were starving, so we headed inside to make tacos and sausage rolls. On the way, my brother talked about wanting his future kids to go hunting but not wanting to take them himself. I gave it some thought and then promised that I’d take them when the time came.