This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On a crisp Friday afternoon in November, looking for what the brochure in my hand said was the “Wildman Gathering,” I turned off the highway onto a rut-filled dirt road and drove slowly past a landscape of brush, small trees, and four curious cows. It was the second weekend of deer-hunting season. Men in camouflage were at that moment crouching down in such terrain all over the state, preparing for their great confrontation with nature. I, on the other hand, was preparing to spend the next 48 hours confronting my maleness. The brochure said I would be “returning to conscious manhood.”

I had no doubt that I could stand a few days reflecting upon that old gray subject What is man? Although I felt that I had passed through my oedipal period with few scratches, rid myself of castration fears, and cleanly cast off such cultural male role models as Sylvester Stallone, I was still disturbed by my own identity as a man. My male bonding consisted solely of daily talks with my fitness instructor, the kind of conversation that is conducted half in English, half in Nautilus. My noble ambitions in life, it seemed, had deteriorated into a lust for money and power. All of my relationships were based on a series of minor deceptions. In short, I was someone who captured the wondrous banality of modern man: a Vanna White with biceps.

That is not to say I had reached the point in my personal spiritual journey at which I thought it important to invest $95 for a weekend of beating on an Indian drum, dancing around a campfire, screaming like a savage, throwing rocks at a man dressed as a woman, and sitting naked for more than an hour in a tent filled with other naked men. But as I would soon learn, a Wildman Gathering is not your basic men’s rap session about how to act more sensitive so that women will like you better.

Wildman weekends have helped fuel an intriguing new consciousness movement that attracts thousands of men who are frustrated with the roles that society has placed them in and who are confused as well by their own needs. Regularly held around the country—in Colorado, Minnesota, California, North Carolina, and even here, on a remote patch of ranchland sixty miles northwest of Waco—Wildman Gatherings are based on the idea that the modern American man has lost his natural masculine psyche, his most primitive, powerful energy. Always trying to please demanding females yet incapable of pleasing himself, man has either become too weak to cope or has turned to false machismo to reassert his feelings of superiority. To find himself again, he must go through a “hero’s journey” and discover deep inside himself the Wildman. And I had thought I was going to a Boy Scout camp for adults.

I drove toward a clearing, where a young man in a cowboy hat was shoveling cow manure into a wheelbarrow and a man with a beard was hunkered down, rubbing the stomach of a dog. The bearded man was Marvin Allen, a therapist and the assistant director of the Austin Men’s Center. He was sponsoring the weekend.

“You know, until we started our center in November 1988, there were something like seventeen women’s resource centers in Austin and not one place for men,” said Allen, a gentle, intelligent-looking man whose master’s thesis in psychology was “The New Male.” He explained, “As a movement, this has just begun to scratch the surface. It’s not like the women’s movement, where women talked about how they were oppressed by men. This is a different movement, where men have to realize they’ve oppressed themselves.”

I nodded pleasantly, even though I had trouble believing him. How many times have we heard this talk about the “new male”? The “emerging sensitive male”? I remembered a 1979 Gentlemen s Quarterly article heralding the age of the new masculinity. It announced that the new man “can have a favorite flower and favorite color.” Such male trends come and go as frequently as circus tents, a point I was about to make when a Volvo pulled up and a wiry middle-aged man jumped out. He was Gary G. John, a counselor and instructor at Richland College in Dallas, who said that he had signed up for the weekend because “I’m getting ready to come out of the closet with male issues.” Seeing my puzzled look, he continued, “Every college in the country will soon have to deal with male issues, and I want to be fully prepared.”

For the rest of the afternoon, one man after another—71 in all—arrived to experience a renaissance of his manhood. I had expected the usual cast of self-help converts, granola heads, ex-hippies, and inner-peace devotees. I hadn’t expected a doctor arriving in a Mercedes, a lawyer, a television anchorman, a couple of Fortune 500 executives, and several engineers and software consultants. Forty-year-old Joah Bennett, a gruff-looking owner of a San Antonio engineering company, decided to drop his real name, Joe Bob, for the weekend because he was tired of “coming across as an old Texas hard-ass.” There was a distinguished-looking 61-year-old scientist and a 50-year-old senior partner in an accounting firm from England. England? “Oh, yes,” said Alan Herberts, who had come from Nottingham to Texas to visit a friend and take in the Wildman Gathering. “All over the world, men have been isolated from one another so they can compete with one other. It’s time—don’t you think?—for men to come together.” Although Austin lawyer Herb Novak was comfortable being seen at such a gathering, he did admit, “When some people hear about this, they think it’s a faggot weekend.” Actually, it felt more like a New Age Elks lodge, the sensitive man’s equivalent of a pool hall.

As I laid out my bedroll in a nearby field, first making sure the cows were gone, I heard the muffled sound of drumbeats like far-off thunder. It came from a clump of oak trees in a pasture. We would soon know the trees as the Sacred Grove. As if heeding a call to war, we grabbed our drums, which we had been asked to bring, and followed the sound. It was time to enter the world of the Wildman.

Somewhere deep in the blood of men—pulsating out of the heart, zipping up and down the arteries, rushing wildly to the brain—is what I like to refer to as the ancient call of the tom-tom, the innate need to take one’s hand and slap it down rhythmically on a flat surface. In my opinion, the uniqueness of the male can be summed up in our desire to turn just about anything we see into a drum set. We love to beat on things. Women don’t. What else does one need in order to recognize the eternal war between the sexes?

Seventy-one men stood or kneeled around a campfire as night fell upon the ranch, and for nearly twenty minutes, without any direction from the leaders, we pounded our drums. There were men with handmade Indian drums, the cowhide stretched across hollowed-out logs. Some brought bongos, and some had prehistoric-looking African drums. One brought a snare drum that he had borrowed from a high school band. John Gelland, an oil executive from Houston, had purchased an $8.99 plastic drum from Toys “R” Us. He was tapping it solemnly, his eyes half shut.

Childhood memories flooded back as I bopped on a borrowed tambourine: the summer I beat drums with my father at Indian Guides, that afternoon in the fourth grade when I first recognized Ringo Starr’s soulful licks as true art. A big man with a closely trimmed beard and penetrating blue eyes rose to talk about the unknown terrors of manhood. John Lee, the founder of the Austin Men’s Center, is one of the best-known leaders in the men’s movement. His book, The Flying Boy: Healing the Wounded Man, has sold 78,000 copies; he has appeared on Oprah Winfrey, and he is in demand nationwide to conduct men’s workshops. But the 38-year-old Lee has none of the trappings of a scholarly philosopher. He cusses a lot in a thick Southern accent, wears workman’s boots, and has a kind of down-home charm often found in the men who sit on benches in front of small-town gas stations.

Lee is a follower of Robert Bly, a Minnesota poet whose writings on manhood have set the tone for the male-advocacy movement. Bly started Wildman Gatherings in the early eighties in the belief that men could find their deepest masculine side only through stories, poems, and myths that uncover the archetypal images of man. He argued that the latter-day male rituals—cars, guns, sports, money, conquest of women—were not working. They pitted men against one another and kept them from expressing their most important emotions. Like Indian boys who fasted alone in the wilderness to receive a vision or African boys who drank from a gourd filled with the tribal leaders’ blood, modern man also needed a rite of passage, one that taught him to bond with other men and to recognize the power within himself.

“We grew up in a force field of women!” Lee announced to us. “We’re in the world of the feminine. Most of us have become what Bly calls ‘soft males,’ which means we’ve related to women and women’s desires for so long that we’re more comfortable around them than we are around men. Remember the sensitive male of the sixties? Yes, he was trying to feel, but he was trying to feel like a woman instead of like a man.”

“Ho!” we all said. We had been told earlier to repeat that Indian word when we wished to respond favorably to a comment.

“The Wildman movement isn’t about oppressing others,” Lee said, perhaps to head off any criticism from those of us who might be wondering if this whole thing was simply a backlash against the feminist movement. “It’s about getting in touch with our real feelings so we don’t have to oppress. True masculinity is learning to grieve, to be able to cry, to be vulnerable.”

Lee’s tears were already coming. He told us about his alcoholic father, who was always emotionally absent or abusive, and his mother, who practically devoured him. “My dad made me afraid of men, and my mother made me afraid of women,” he said. “She emotionally incested me. She penetrated my psyche. She told me not to be like my father, and she tried to make me her ‘little man.’ I grew up thinking I’d be all right if I only pleased her. Men, I’ve been trying to separate myself from Mother for the rest of my life.”

One by one, we introduced ourselves and named our mothers. I studied the faces of the men. A few had that eager look that said they were meant for success; others seemed worn down by the slow corrosion of frustration from a lifetime of trying to get things right.

Lee told us to look beyond the grove, a hundred yards away. “I want all of you to take your mothers out there and leave them,” said Lee. “Banish them from the Sacred Grove! This is our weekend! We will not be controlled by them!”

“Ho!” we cried, standing up and pushing our mothers out into the darkness. We took to our drums, our beats now frenzied and full of hope.

Was this the key to manhood? I went to bed early and spent the rest of the evening trying to distinguish between a man’s feelings and a woman’s. If men felt things differently, as John Lee and Marvin Allen kept telling us, how exactly did they feel? Were they more aggressive? Did they like to play more? Did they really grieve more deeply than women? And what, please, did it mean to be truly masculine?

“I define masculinity differently everytime someone asks me,” Lee confided to me the next morning at breakfast. “If I had to say something now, it’s that true masculinity comes when a man knows when to wield a metaphorical sword and when to sheathe the sword. True masculinity is not trampling on the souls of men, women, and children.”

I stared at him, as mystified as ever. No wonder thousands of men settle for shooting deer.

In the Sacred Grove the atmosphere had the healthy excitement of the morning before a big football game. Many of the men felt as if they were on the verge of a discovery. “My sons think I’m weird coming to something like this,” said 44-year-old Mike Sadaj, a burly divorced Vietnam veteran who is a Houston computer consultant. He was wearing a gimme cap, a Marines T-shirt, and camouflage pants. “But my life has literally changed since I started this men’s work. I now can share my pain with other men, and I’ve never been able to do something like this—not even during the war.”

After our Saturday morning drumming, Lee read some poetry: “When I’m quiet and silent as the ground/Then I talk the low tones of thunder to everyone.” We replied, “Ho!” Then Marvin Allen told us about his failed attempts to become a man. He had tried hunting, sex, marriage and family, business, divorce, advanced education, and religion. “I did all the things culture tells you to do to become a man,” Allen said. “I tried being successful and superior. I played sports as if my life were on the line. I abandoned my son emotionally so I could go out and become a man. But the only thing that makes you a man is when you believe you’re a man.”

And at what point do you believe you’re a man? aha! We had come to the moment of truth. Allen smiled. “You know you’re a man,” he said, “when you find, deep inside you”—he caught his breath as he paused for emphasis—“that primitive being covered with hair, the Wildman!”

“Ho!” we cried.

The Wildman, a figure referred to in ancient myths and fairy tales, is what makes man a noble warrior and a great king. It is the rarely tapped source of strength that allows us to express our most honest anger, our grief, and our frolicsome spirit. A century ago, Thoreau referred to the Wildman when he wrote, “I would have every man so much like a wild antelope. . . . The most alive is the wildest.”

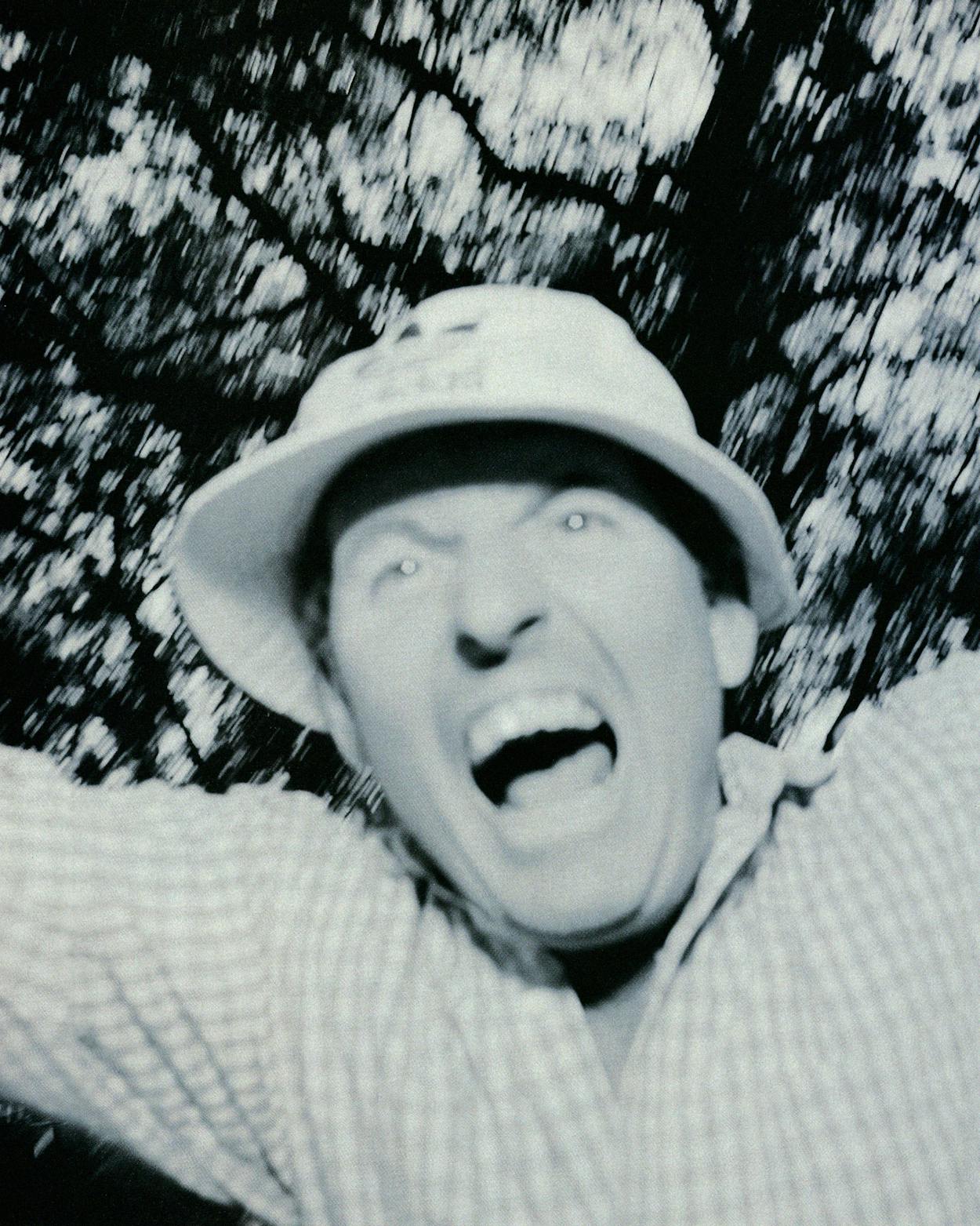

Allen warned us not to confuse our Wildman with our bestial, violent side, called the Savageman. As our drumming swelled into a wild upsurge, Allen asked us to dance like Savagemen. Without hesitation men leaped up screaming, grabbing sticks, and shaking them at one another. One man lay on his back, kicking; another swung wildly from a tree. The largest man at the gathering, Randall Jones, a contemplative Austin archivist and librarian, assumed a bearlike posture and began snarling at Carl Schade, an Austin electrical technician and the second-largest man there. Schade growled back, and suddenly they were grappling like two grizzlies.

Around the campfire we went, acting like a street gang. Then Allen stopped us and said that it was time to dance like Wildmen, gleeful and in harmony with the earth. Now what were we to do? I had felt remarkably comfortable during the Savageman segment, shouting profanities in Pig Latin. But a Wildman?

The drums surged, and off we went. Shirley Fryar, who had left his job as a United Parcel Service supervisor to return to college and take the courses he had always wanted to take—including dance—performed some kind of twirling Baryshnikov thing. Others waltzed in slow motion, some closed their eyes and swayed, and the man who had been hanging out of the tree was now hugging it. After giving myself a pep talk (this could, after all, be the event that would change my life), I found myself doing a ring-around-the-rosy dance on my tiptoes. Quickly out of control, my feet moved faster and faster. I whirled toward the pasture, skipping over cow pies and ant beds. I must have looked like a prisoner on the run, the dogs baying not far behind.

By the end of the Wildman dance, however, we were exhilarated. Next, Allen instructed us to do the King March, “to show your pride without arrogance.” In single file we marched around the grove, our heads held high and our chests thrust out. Indeed, the Wildman spirit was consuming us. During a skit to help us recognize the power our mothers exert over us—or, more accurately, to show how afraid we really are of them—a man, dressed as a woman in a long skirt, a wig, and makeup, berated his son for dating the wrong women, not coming home regularly enough for dinner, and forgetting that he was “put on earth just for me to love.”

My fellow Wildmen went absolutely bonkers. “Get the hell out of our grove!” one yelled.

“Lady, you’re making me crazy,” cried another.

“No wonder he’ll turn into a son of a bitch,” screamed a third.

“Let’s get her!” we all shrieked happily, and we grabbed our drums to beat the woman away. The actor, his eyes getting huge, realized we weren’t kidding. He raced off, holding his skirt up so he wouldn’t trip. As hard as we tried, we couldn’t gain on him. But we had one last hope. As the man-woman dashed over a cattle guard into a far pasture, a few of us slowed down, grabbed stones from the ground, and started throwing them at him. I seized a rock and let it fly. It arched over the plains, carried by an invisible wind, and landed five feet from him. To my deep satisfaction—was it my Savageman? my Wildman? or a simple nostalgia for the rock-throwing contests of my boyhood?—the actor jumped like a kangaroo.

The point of the exercise, I assumed, was to teach men to break away from their mothers. If men don’t, Lee later told us, they will always project a demanding-mother figure onto the women they are with. They will have poor relationships, either quavering under the fear of abandonment or trying to dominate women.

Lee’s underlying message was that we have not reached our full potential as men because our parents never provided us with the right role models. It’s the old idea that most of our problems can be traced directly to our parents. In a long guided meditation, we visualized our mothers and fathers. Lee asked us to feel how isolated we were from our fathers, men who were crushed by economic burdens and done in by fatigue and as a result had little time for us.

I wondered if, deep down, the men were really buying into this. Not everyone can fit his parents into such harsh, unyielding categories. Yet within moments, there was sniffling around the circle, which soon turned into sobbing. One man wept into his hands, his shoulders rising to his ears. Another, as he cried, caught his tears with his tongue. Eventually, from at least a dozen men came a mournful wailing, almost like a howl. It was so astonishing that I wondered briefly if it was for real. But it was; the crying got louder. Obediently, at Lee’s suggestion, we paired off and walked hand in hand into the pasture to discuss our feelings of sadness. If men do repress their emotions more than women do, you couldn’t tell it here.

All of the men seemed quite willing to describe the most excruciating details of their lives. Jon Marshall, a 29-year-old social worker, shared a letter he had written to his mother. Marshall had grown up in a household of women and spent his adolescence lifting weights, working on cars, and growing a beard as ways of proving his manhood. He wrote, “I’m always defending myself to you, Mom, proving myself to you, even when you’re not here. . . . I want to be intimate with people, and you never taught me how.”

There was no question that the Wildman Gathering exposed the painful loneliness that a number of men feel—and the relief that can be found just by having someone with whom to share those emotions. Who could not be touched by someone like Charles Hollabaugh, a shy Austin scientist who at 61 was the oldest man there? “After all these years,” he told me, “I’m learning how to overcome my insecurity with people. It’s like I’ve spent a lifetime hiding, and now I don’t have to.”

Still, I wondered what was particularly “male” about the message of this movement. Most people, men and women, have trouble negotiating intimacy. We are all molded by the history of our parents. We spend years, regardless of gender, struggling to establish our own identity. There’s no doubt that men can benefit from the companionship of other men and that we could all use a strong, loving father figure—but do we have to go through such elaborately contrived and occasionally silly ritualistic behavior to understand that? Why, I wondered, did we have to gather in a pack and shove women away, to look at them as potential sources of destruction, just to get a sense of who we are as men?

Maybe you’ll get a better feel for what we’re doing after tonight,” Marvin Allen said toward the end of the second day.

He was referring to the purification ceremony, the big event of the weekend. Under a full moon, all of us took off our clothes and stood shivering beside a fire as we prepared to enter sweat lodges: two large tents covered by tarps to prevent the escape of heat. Sweat lodges were the traditional places where American Indians would sit through the night, in the symbolic womb of Mother Earth, to sweat out the impurities of their bodies and discover their own true spiritual nature.

Inside each tent was a small hole in which hot coals would be laid. “This is a cleansing,” said the Indian who was leading the ceremony. “If you fight the heat, then you will lose.” Excitedly, we stared at one another, the great brotherhood of man—fat and thin, bald and shaggy, tight-assed and saggy-bottomed. This, we realized, would be our hero’s journey, our mythical rite of passage. Our pale bodies glimmering in the firelight, we stepped forward to our assigned tents.

I got one of the last available spots in my tent, inches from the edge of the fire hole. No problem, I thought. I belonged to a health club. I worked out. I was in far better shape than most of the men here.

The flap went down, throwing us into darkness. “We come to look into the heart of the sacred mystery,” said our leader.

“Ho!” we replied.

“Bring in the rocks,” he said.

The flap came up, and a red-hot, smoldering lava rock the size of a baby’s head was pushed through with a shovel and deposited in the hole. Then came another and then another, each one singeing the hair on my legs. The flap went down again, and our leader said an Indian prayer. Suddenly he flung ladles of water over the coals, instantly creating a wall of steam. My God! My face was on fire! I stifled a scream, threw my hands up to my head, and, amazingly, found no flames. But the leader kept ladling. There was more steam. More heat. My body twitched like a bug on a hot skillet.

“It is here that we come in touch with the holy,” our leader said. My lungs were straining for air, my throat making a rasping sound. “Each one here shall offer up a prayer.” Each person? That was at least forty prayers! My head began to droop, straight down toward the coals. I frantically pulled myself back, just in time to get hit by another wave of steam. While our leader sang Indian songs and beat on his drum, the men quietly and lengthily offered up their prayers, one after another, praying for love, understanding, peace, healing. I was incredulous! Why didn’t anyone else seem bothered by the heat? They all appeared to be meditating. A numbness was developing in the hollow of my chest. My face already felt like a slab of pasteboard, and my two hairless legs like sticks of kindling.

When it was my turn to pray, I mumbled something about help for my soul, and I am not sure what happened next. Did I have a vision? A sign from a spirit? All I remember is that strong hands were helping me up, guiding me to the tent flap. Half-carried, half-limping, close to passing out from heat exhaustion, I staggered outside.

For several minutes after I recovered, I stood alone, looking at the moonlit landscape, consumed by shame. It was like that time in junior high when I was the only boy in gym class who couldn’t climb the ropes. Inside the tent, the prayers resumed: men calling out to the Great Spirit to grant them strength. Almost an hour later, when they came out, they linked arms around the campfire, tears in their eyes, sweat dripping from their naked loins. I watched from a distance, wondering if my masculinity was slipping away, like the ebbing tide.

On the final day of the Wildman Gathering, Lee wanted to leave us with the memory of what the new man should be. He asked us to picture the perfect female, “the woman who comes at night to you in dreams.” He told us, “She is not your wife, she is not your mama, she is not your sister. She is the invisible bride. She is the best part of you.” Still nursing my wounds, I tried to concentrate on my own Mona Lisa, a woman with flawless skin and eyes as green as mint. “You never have to look outside yourself,” Lee continued, “to find sensitivity, gentleness, kindness. It is the woman right there inside you.”

Lee asked if anyone was ready to marry this invisible bride, to join his masculine and feminine sides together. One man stepped forward. We were going to have a wedding ceremony! The groom was 34-year-old Clark Belts, a linebacker-size former construction worker who now owns an Austin fundraising company. As we gathered around, Belts stood before Lee and Allen, his head bowed, his invisible bride at his side.

“Father, Spirit,” said Allen, “bless these two lives.” He read more poetry, and then Lee said, “I now pronounce you . . . Man.” The men all cheered, banged on their drums, and danced madly around the fire. Victory was sweet. They had become great primitive Wildmen, restored to conscious manhood. Hell, maybe they didn’t need women in this world as much as they thought they did.

As I gathered up my things to leave, I wondered if I was one of those “soft males,” incapable of discovering who he really is. Had I truly failed to find my masculinity? Or was my failure in the sweat lodge a result of my doubts that the Wildman weekend had anything new to say? Perhaps the movement was once again turning manhood into another prize to be earned, a privilege that comes from some magical ritual. But what I had hoped to find was a movement that would help men appreciate the never-ending journey we must all take to find our own particular meaning in life. There are no quick answers or shortcuts; we discover the best parts of ourselves in myriad ways. Maybe the Wildman’s way was not my way.

I hugged some of the men good-bye. Driving off down the rut-filled road, I heard the sound of drumbeats coming from the Sacred Grove. The beating continued to ring in my ears even as I turned onto the highway. I took a deep breath and headed toward civilization, away from a territory I did not know.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads